Data Structures and Programming Spring 2016, Final Exam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Alternative to Fibonacci Heaps with Worst Case Rather Than Amortized Time Bounds∗

Relaxed Fibonacci heaps: An alternative to Fibonacci heaps with worst case rather than amortized time bounds¤ Chandrasekhar Boyapati C. Pandu Rangan Department of Computer Science and Engineering Indian Institute of Technology, Madras 600036, India Email: [email protected] November 1995 Abstract We present a new data structure called relaxed Fibonacci heaps for implementing priority queues on a RAM. Relaxed Fibonacci heaps support the operations find minimum, insert, decrease key and meld, each in O(1) worst case time and delete and delete min in O(log n) worst case time. Introduction The implementation of priority queues is a classical problem in data structures. Priority queues find applications in a variety of network problems like single source shortest paths, all pairs shortest paths, minimum spanning tree, weighted bipartite matching etc. [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] In the amortized sense, the best performance is achieved by the well known Fibonacci heaps. They support delete and delete min in amortized O(log n) time and find min, insert, decrease key and meld in amortized constant time. Fast meldable priority queues described in [1] achieve all the above time bounds in worst case rather than amortized time, except for the decrease key operation which takes O(log n) worst case time. On the other hand, relaxed heaps described in [2] achieve in the worst case all the time bounds of the Fi- bonacci heaps except for the meld operation, which takes O(log n) worst case ¤Please see Errata at the end of the paper. 1 time. The problem that was posed in [1] was to consider if it is possible to support both decrease key and meld simultaneously in constant worst case time. -

Game Trees, Quad Trees and Heaps

CS 61B Game Trees, Quad Trees and Heaps Fall 2014 1 Heaps of fun R (a) Assume that we have a binary min-heap (smallest value on top) data structue called Heap that stores integers and has properly implemented insert and removeMin methods. Draw the heap and its corresponding array representation after each of the operations below: Heap h = new Heap(5); //Creates a min-heap with 5 as the root 5 5 h.insert(7); 5,7 5 / 7 h.insert(3); 3,7,5 3 /\ 7 5 h.insert(1); 1,3,5,7 1 /\ 3 5 / 7 h.insert(2); 1,2,5,7,3 1 /\ 2 5 /\ 7 3 h.removeMin(); 2,3,5,7 2 /\ 3 5 / 7 CS 61B, Fall 2014, Game Trees, Quad Trees and Heaps 1 h.removeMin(); 3,7,5 3 /\ 7 5 (b) Consider an array based min-heap with N elements. What is the worst case running time of each of the following operations if we ignore resizing? What is the worst case running time if we take into account resizing? What are the advantages of using an array based heap vs. using a BST-based heap? Insert O(log N) Find Min O(1) Remove Min O(log N) Accounting for resizing: Insert O(N) Find Min O(1) Remove Min O(N) Using a BST is not space-efficient. (c) Your friend Alyssa P. Hacker challenges you to quickly implement a max-heap data structure - "Hah! I’ll just use my min-heap implementation as a template", you think to yourself. -

Heaps a Heap Is a Complete Binary Tree. a Max-Heap Is A

Heaps Heaps 1 A heap is a complete binary tree. A max-heap is a complete binary tree in which the value in each internal node is greater than or equal to the values in the children of that node. A min-heap is defined similarly. 97 Mapping the elements of 93 84 a heap into an array is trivial: if a node is stored at 90 79 83 81 index k, then its left child is stored at index 42 55 73 21 83 2k+1 and its right child at index 2k+2 01234567891011 97 93 84 90 79 83 81 42 55 73 21 83 CS@VT Data Structures & Algorithms ©2000-2009 McQuain Building a Heap Heaps 2 The fact that a heap is a complete binary tree allows it to be efficiently represented using a simple array. Given an array of N values, a heap containing those values can be built, in situ, by simply “sifting” each internal node down to its proper location: - start with the last 73 73 internal node * - swap the current 74 81 74 * 93 internal node with its larger child, if 79 90 93 79 90 81 necessary - then follow the swapped node down 73 * 93 - continue until all * internal nodes are 90 93 90 73 done 79 74 81 79 74 81 CS@VT Data Structures & Algorithms ©2000-2009 McQuain Heap Class Interface Heaps 3 We will consider a somewhat minimal maxheap class: public class BinaryHeap<T extends Comparable<? super T>> { private static final int DEFCAP = 10; // default array size private int size; // # elems in array private T [] elems; // array of elems public BinaryHeap() { . -

Advanced Data Structures

Advanced Data Structures PETER BRASS City College of New York CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521880374 © Peter Brass 2008 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published in print format 2008 ISBN-13 978-0-511-43685-7 eBook (EBL) ISBN-13 978-0-521-88037-4 hardback Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of urls for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Contents Preface page xi 1 Elementary Structures 1 1.1 Stack 1 1.2 Queue 8 1.3 Double-Ended Queue 16 1.4 Dynamical Allocation of Nodes 16 1.5 Shadow Copies of Array-Based Structures 18 2 Search Trees 23 2.1 Two Models of Search Trees 23 2.2 General Properties and Transformations 26 2.3 Height of a Search Tree 29 2.4 Basic Find, Insert, and Delete 31 2.5ReturningfromLeaftoRoot35 2.6 Dealing with Nonunique Keys 37 2.7 Queries for the Keys in an Interval 38 2.8 Building Optimal Search Trees 40 2.9 Converting Trees into Lists 47 2.10 -

L11: Quadtrees CSE373, Winter 2020

L11: Quadtrees CSE373, Winter 2020 Quadtrees CSE 373 Winter 2020 Instructor: Hannah C. Tang Teaching Assistants: Aaron Johnston Ethan Knutson Nathan Lipiarski Amanda Park Farrell Fileas Sam Long Anish Velagapudi Howard Xiao Yifan Bai Brian Chan Jade Watkins Yuma Tou Elena Spasova Lea Quan L11: Quadtrees CSE373, Winter 2020 Announcements ❖ Homework 4: Heap is released and due Wednesday ▪ Hint: you will need an additional data structure to improve the runtime for changePriority(). It does not affect the correctness of your PQ at all. Please use a built-in Java collection instead of implementing your own. ▪ Hint: If you implemented a unittest that tested the exact thing the autograder described, you could run the autograder’s test in the debugger (and also not have to use your tokens). ❖ Please look at posted QuickCheck; we had a few corrections! 2 L11: Quadtrees CSE373, Winter 2020 Lecture Outline ❖ Heaps, cont.: Floyd’s buildHeap ❖ Review: Set/Map data structures and logarithmic runtimes ❖ Multi-dimensional Data ❖ Uniform and Recursive Partitioning ❖ Quadtrees 3 L11: Quadtrees CSE373, Winter 2020 Other Priority Queue Operations ❖ The two “primary” PQ operations are: ▪ removeMax() ▪ add() ❖ However, because PQs are used in so many algorithms there are three common-but-nonstandard operations: ▪ merge(): merge two PQs into a single PQ ▪ buildHeap(): reorder the elements of an array so that its contents can be interpreted as a valid binary heap ▪ changePriority(): change the priority of an item already in the heap 4 L11: Quadtrees CSE373, -

Introduction to Algorithms and Data Structures

Introduction to Algorithms and Data Structures Markus Bläser Saarland University Draft—Thursday 22, 2015 and forever Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Binary search . .1 1.2 Machine model . .3 1.3 Asymptotic growth of functions . .5 1.4 Running time analysis . .7 1.4.1 On foot . .7 1.4.2 By solving recurrences . .8 2 Sorting 11 2.1 Selection-sort . 11 2.2 Merge sort . 13 3 More sorting procedures 16 3.1 Heap sort . 16 3.1.1 Heaps . 16 3.1.2 Establishing the Heap property . 18 3.1.3 Building a heap from scratch . 19 3.1.4 Heap sort . 20 3.2 Quick sort . 21 4 Selection problems 23 4.1 Lower bounds . 23 4.1.1 Sorting . 25 4.1.2 Minimum selection . 27 4.2 Upper bounds for selecting the median . 27 5 Elementary data structures 30 5.1 Stacks . 30 5.2 Queues . 31 5.3 Linked lists . 33 6 Binary search trees 36 6.1 Searching . 38 6.2 Minimum and maximum . 39 6.3 Successor and predecessor . 39 6.4 Insertion and deletion . 40 i ii CONTENTS 7 AVL trees 44 7.1 Bounds on the height . 45 7.2 Restoring the AVL tree property . 46 7.2.1 Rotations . 46 7.2.2 Insertion . 46 7.2.3 Deletion . 49 8 Binomial Heaps 52 8.1 Binomial trees . 52 8.2 Binomial heaps . 54 8.3 Operations . 55 8.3.1 Make heap . 55 8.3.2 Minimum . 55 8.3.3 Union . 56 8.3.4 Insert . -

AVL Tree, Bayer Tree, Heap Summary of the Previous Lecture

DATA STRUCTURES AND ALGORITHMS Hierarchical data structures: AVL tree, Bayer tree, Heap Summary of the previous lecture • TREE is hierarchical (non linear) data structure • Binary trees • Definitions • Full tree, complete tree • Enumeration ( preorder, inorder, postorder ) • Binary search tree (BST) AVL tree The AVL tree (named for its inventors Adelson-Velskii and Landis published in their paper "An algorithm for the organization of information“ in 1962) should be viewed as a BST with the following additional property: - For every node, the heights of its left and right subtrees differ by at most 1. Difference of the subtrees height is named balanced factor. A node with balance factor 1, 0, or -1 is considered balanced. As long as the tree maintains this property, if the tree contains n nodes, then it has a depth of at most log2n. As a result, search for any node will cost log2n, and if the updates can be done in time proportional to the depth of the node inserted or deleted, then updates will also cost log2n, even in the worst case. AVL tree AVL tree Not AVL tree Realization of AVL tree element struct AVLnode { int data; AVLnode* left; AVLnode* right; int factor; // balance factor } Adding a new node Insert operation violates the AVL tree balance property. Prior to the insert operation, all nodes of the tree are balanced (i.e., the depths of the left and right subtrees for every node differ by at most one). After inserting the node with value 5, the nodes with values 7 and 24 are no longer balanced. -

Leftist Heap: Is a Binary Tree with the Normal Heap Ordering Property, but the Tree Is Not Balanced. in Fact It Attempts to Be Very Unbalanced!

Leftist heap: is a binary tree with the normal heap ordering property, but the tree is not balanced. In fact it attempts to be very unbalanced! Definition: the null path length npl(x) of node x is the length of the shortest path from x to a node without two children. The null path lengh of any node is 1 more than the minimum of the null path lengths of its children. (let npl(nil)=-1). Only the tree on the left is leftist. Null path lengths are shown in the nodes. Definition: the leftist heap property is that for every node x in the heap, the null path length of the left child is at least as large as that of the right child. This property biases the tree to get deep towards the left. It may generate very unbalanced trees, which facilitates merging! It also also means that the right path down a leftist heap is as short as any path in the heap. In fact, the right path in a leftist tree of N nodes contains at most lg(N+1) nodes. We perform all the work on this right path, which is guaranteed to be short. Merging on a leftist heap. (Notice that an insert can be considered as a merge of a one-node heap with a larger heap.) 1. (Magically and recursively) merge the heap with the larger root (6) with the right subheap (rooted at 8) of the heap with the smaller root, creating a leftist heap. Make this new heap the right child of the root (3) of h1. -

Lecture 6 — February 9, 2017 1 Wrapping up on Hashing

CS 224: Advanced Algorithms Spring 2017 Lecture 6 | February 9, 2017 Prof. Jelani Nelson Scribe: Albert Chalom 1 Wrapping up on hashing Recall from las lecture that we showed that when using hashing with chaining of n items into m C log n bins where m = Θ(n) and hash function h :[ut] ! m that if h is from log log n wise family, then no C log n linked list has size > log log n . 1.1 Using two hash functions Azar, Broder, Karlin, and Upfal '99 [1] then used two hash functions h; g :[u] ! [m] that are fully random. Then ball i is inserted in the least loaded of the 2 bins h(i); g(i), and ties are broken randomly. log log n Theorem: Max load is ≤ log 2 + O(1) with high probability. When using d instead of 2 hash log log n functions we get max load ≤ log d + O(1) with high probability. n 1.2 Breaking n into d slots n V¨ocking '03 [2] then considered breaking our n buckets into d slots, and having d hash functions n h1; h2; :::; hd that hash into their corresponding slot of size d . Then insert(i), loads i in the least loaded of the h(i) bins, and breaks tie by putting i in the left most bin. log log n This improves the performance to Max Load ≤ where 1:618 = φ2 < φ3::: ≤ 2. dφd 1.3 Survey: Mitzenmacher, Richa, Sitaraman [3] Idea: Let Bi denote the number of bins with ≥ i balls. -

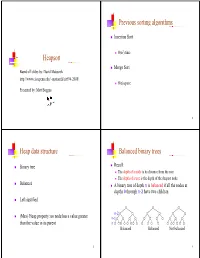

Heapsort Previous Sorting Algorithms G G Heap Data Structure P Balanced

Previous sortinggg algorithms Insertion Sort 2 O(n ) time Heapsort Merge Sort Based off slides by: David Matuszek http://www.cis.upenn.edu/~matuszek/cit594-2008/ O(n) space PtdbMttBPresented by: Matt Boggus 2 Heap data structure Balanced binary trees Binary tree Recall: The dthfdepth of a no de iitditis its distance f rom th e root The depth of a tree is the depth of the deepest node Balanced A binary tree of depth n is balanced if all the nodes at depths 0 through n-2 have two children Left-justified n-2 (Max) Heap property: no node has a value greater n-1 than the value in its parent n Balanced Balanced Not balanced 3 4 Left-jjyustified binary trees Buildinggp up to heap sort How to build a heap A balanced binary tree of depth n is left- justified if: n it has 2 nodes at depth n (the tree is “full”)or ), or k How to maintain a heap it has 2 nodes at depth k, for all k < n, and all the leaves at dept h n are as fa r le ft as poss i ble How to use a heap to sort data Left-justified Not left-justified 5 6 The heappp prop erty siftUp A node has the heap property if the value in the Given a node that does not have the heap property, you can nodide is as large as or larger t han th e va lues iiin its give it the heap property by exchanging its value with the children value of the larger child 12 12 12 12 14 8 3 8 12 8 14 8 14 8 12 Blue node has Blue node has Blue node does not Blue node does not Blue node has heap property heap property have heap property have heap property heap property All leaf nodes automatically have -

Data Structures Binary Trees and Their Balances Heaps Tries B-Trees

Data Structures Tries Separated chains ≡ just linked lists for each bucket. P [one list of size exactly l] = s(1=m)l(1 − 1=m)n−l. Since this is a Note: Strange structure due to finals topics. Will improve later. Compressing dictionary structure in a tree. General tries can grow l P based on the dictionary, and quite fast. Long paths are inefficient, binomial distribution, easily E[chain length] = (lP [len = l]) = α. Binary trees and their balances so we define compressed tries, which are tries with no non-splitting Expected maximum list length vertices. Initialization O(Σl) for uncompressed tries, O(l + Σ) for compressed (we are only making one initialization of a vertex { the X s j AVL trees P [max len(j) ≥ j) ≤ P [len(i) ≥ j] ≤ m (1=m) last one). i j i Vertices contain -1,0,+1 { difference of balances between the left and T:Assuming all l-length sequences come with uniform probability and we have a sampling of size n, E[c − trie size] = log d. j−1 the right subtree. Balance is just the maximum depth of the subtree. k Q (s − k) P = k=0 (1=m)j−1 ≤ s(s=m)j−1=j!: Analysis: prove by induction that for depth k, there are between Fk P:qd ≡ probability trie has depth d. E[c − triesize] = d d(qd − j! k P and 2 vertices in every tree. Since balance only shifts by 1, it's pretty qd+1) = d qd. simple. Calculate opposite event { trie is within depth d − 1. -

Lecture Notes of CSCI5610 Advanced Data Structures

Lecture Notes of CSCI5610 Advanced Data Structures Yufei Tao Department of Computer Science and Engineering Chinese University of Hong Kong July 17, 2020 Contents 1 Course Overview and Computation Models 4 2 The Binary Search Tree and the 2-3 Tree 7 2.1 The binary search tree . .7 2.2 The 2-3 tree . .9 2.3 Remarks . 13 3 Structures for Intervals 15 3.1 The interval tree . 15 3.2 The segment tree . 17 3.3 Remarks . 18 4 Structures for Points 20 4.1 The kd-tree . 20 4.2 A bootstrapping lemma . 22 4.3 The priority search tree . 24 4.4 The range tree . 27 4.5 Another range tree with better query time . 29 4.6 Pointer-machine structures . 30 4.7 Remarks . 31 5 Logarithmic Method and Global Rebuilding 33 5.1 Amortized update cost . 33 5.2 Decomposable problems . 34 5.3 The logarithmic method . 34 5.4 Fully dynamic kd-trees with global rebuilding . 37 5.5 Remarks . 39 6 Weight Balancing 41 6.1 BB[α]-trees . 41 6.2 Insertion . 42 6.3 Deletion . 42 6.4 Amortized analysis . 42 6.5 Dynamization with weight balancing . 43 6.6 Remarks . 44 1 CONTENTS 2 7 Partial Persistence 47 7.1 The potential method . 47 7.2 Partially persistent BST . 48 7.3 General pointer-machine structures . 52 7.4 Remarks . 52 8 Dynamic Perfect Hashing 54 8.1 Two random graph results . 54 8.2 Cuckoo hashing . 55 8.3 Analysis . 58 8.4 Remarks . 59 9 Binomial and Fibonacci Heaps 61 9.1 The binomial heap .