Mining Transcriptomic Data to Study the Origins and Evolution of a Plant Allopolyploid Complex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) James Andrew Lackey Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1977 A synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) James Andrew Lackey Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Lackey, James Andrew, "A synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) " (1977). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 5832. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/5832 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Final Report Template

Native Legumes as a Grain Crop for Diversification in Australia RIRDC Publication No. 10/223 RIRDCInnovation for rural Australia Native Legumes as a Grain Crop for Diversification in Australia by Megan Ryan, Lindsay Bell, Richard Bennett, Margaret Collins and Heather Clarke October 2011 RIRDC Publication No. 10/223 RIRDC Project No. PRJ-000356 © 2011 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-74254-188-4 ISSN 1440-6845 Native Legumes as a Grain Crop for Diversification in Australia Publication No. 10/223 Project No. PRJ-000356 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication. -

Allopolyploidy and Root Nodule Symbiosis in Glycine

TWO TO TANGO: ALLOPOLYPLOIDY AND ROOT NODULE SYMBIOSIS IN GLYCINE SUBGENUS GLYCINE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Adrian Federico Powell January 2017 © 2017 Adrian Federico Powell TWO TO TANGO: ALLOPOLYPLOIDY AND ROOT NODULE SYMBIOSIS IN GLYCINE SUBGENUS GLYCINE Adrian Federico Powell, Ph.D. Cornell University 2017 Polyploidy (or whole genome duplication) and root nodule symbioses with bacteria (termed ‘rhizobia’) have both been important phenomena in the evolutionary history of the legume family (Leguminosae). Recently, it has been proposed that polyploidy may have played a critical role in the development or refinement of nodulation. Given the varied potential impacts of polyploidy, effects on biotic interactions are plausible. However, direct studies of the interactions between these phenomena in symbiotic, nodule-forming species are lacking. In this dissertation, using a complex of recently formed allopolyploids in Glycine subgenus Glycine, the perennial relatives of soybean, we examined (1) the root metabolites and symbiotic signaling capacity of multiple allopolyploid species relative to the diploid progenitor species that hybridized to form each allopolyploid, (2) the nodulation-related responses of allopolyploids and diploid progenitors to rhizobia and (3) the transcriptome-level responses to inoculation in allopolyploid G. dolichocarpa (T2) and its diploid progenitors. These objectives were pursued using a variety of approaches including root metabolite profiling, inoculation trials, and RNA sequencing. We found that, while there were no common transgressive patterns in the root metabolite profiles of allopolyploids in the complex, one of the progenitors of T2 had distinctive root metabolite and exudate profiles; profiles of symbiotic signaling metabolites were also altered in the allopolyploid. -

Jervis Bay Territory Page 1 of 50 21-Jan-11 Species List for NRM Region (Blank), Jervis Bay Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Evolution of Angiosperm Pollen. 7. Nitrogen-Fixing Clade1

Evolution of Angiosperm Pollen. 7. Nitrogen-Fixing Clade1 Authors: Jiang, Wei, He, Hua-Jie, Lu, Lu, Burgess, Kevin S., Wang, Hong, et. al. Source: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 104(2) : 171-229 Published By: Missouri Botanical Garden Press URL: https://doi.org/10.3417/2019337 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non - commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/journals/Annals-of-the-Missouri-Botanical-Garden on 01 Apr 2020 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Access provided by Kunming Institute of Botany, CAS Volume 104 Annals Number 2 of the R 2019 Missouri Botanical Garden EVOLUTION OF ANGIOSPERM Wei Jiang,2,3,7 Hua-Jie He,4,7 Lu Lu,2,5 POLLEN. 7. NITROGEN-FIXING Kevin S. Burgess,6 Hong Wang,2* and 2,4 CLADE1 De-Zhu Li * ABSTRACT Nitrogen-fixing symbiosis in root nodules is known in only 10 families, which are distributed among a clade of four orders and delimited as the nitrogen-fixing clade. -

DRAFT 25/10/90; Plant List Updated Oct. 1992; Notes Added June 2021

DRAFT 25/10/90; plant list updated Oct. 1992; notes added June 2021. PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE CONSERVATION VALUES OF OPEN COUNTRY PADDOCK, BOOLARDY STATION Allan H. Burbidge and J.K. Rolfe INTRODUCTION Boolardy Station is situated about 150 km north of Yalgoo and 140 km west-north-west of Cue, in the Shire of Murchison, Western Australia. Open Country Paddock (about 16 000 ha) is in the south-east corner of the station, at 27o05'S, 116o50'E. The most prominent named feature is Coolamooka Hill, near the eastern boundary of the paddock. There are no conservation reserves in this region, although there are some small reserves set aside for various other purposes. Previous biological data for the station consist of broad scale vegetation mapping and land system mapping. Beard (1976) mapped the entire Murchison region at 1: 1 000 000. The Open Country Paddock area was mapped as supporting mulga woodlands and shrublands. More detailed mapping of land system units for rangeland assessment purposes has been carried out more recently at a scale of 1: 40 000 (Payne and Curry in prep.). Seven land systems were identified in open Country Paddock (Fig. 1). Apart from these studies, no detailed biological survey work appears to have been done in the area. Open Country Paddock has been only lightly grazed by domestic stock because of the presence of Kite-leaf Poison (Gastrolobium laytonii) and a lack of fresh water. Because of this and the generally good condition of the paddock and presence of a wide range of plant species, P.J. -

Subtractive Libraries for Prospecting Differentially Expressed Genes in the Soybean Under Water Deficit

Genetics and Molecular Biology, 35, 1 (suppl), 304-314 (2012) Copyright © 2012, Sociedade Brasileira de Genética. Printed in Brazil www.sbg.org.br Research Article Subtractive libraries for prospecting differentially expressed genes in the soybean under water deficit Fabiana Aparecida Rodrigues1, Juliana Marcolino-Gomes1, Josirlei de Fátima Corrêa Carvalho1, Leandro Costa do Nascimento2, Norman Neumaier1, José Renato Bouças Farias1, Marcelo Falsarella Carazzolle2, Francismar Corrêa Marcelino1 and Alexandre Lima Nepomuceno1 1Embrapa Soja, Laboratório de Biotecnologia Vegetal, Londrina, PR, Brazil. 2Departamento de Genética, Evolução e Bioagentes, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, SP, Brazil. Abstract Soybean has a wide range of applications in the industry and, due to its crop potential, its improvement is widely de- sirable. During drought conditions, soybean crops suffer significant losses in productivity. Therefore, understanding the responses of the soybean under this stress is an effective way of targeting crop improvement techniques. In this study, we employed the Suppressive Subtractive Hybridization (SSH) technique to investigate differentially ex- pressed genes under water deficit conditions. Embrapa 48 and BR 16 soybean lines, known as drought-tolerant and -sensitive, respectively, were grown hydroponically and subjected to different short-term periods of stress by with- holding the nutrient solution. Using this approach, we have identified genes expressed during the early response to water deficit in roots and leaves. -

Hermantheresa Thesis Dept V6 Th

EVALUATION OF RESISTANCE IN GLYCINE MAX TO FUSARIUM VIRGULIFORME AND IN PERENNIAL GLYCINE SPECIES TO PHAKOPSORA PACHYRHIZI AND HETERODERA GLYCINES BY THERESA HERMAN THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2020 Urbana, Illinois Master’s Committee: Professor Glen L. Hartman, Chair Assistant Professor Santiago Mideros Professor Andrew N. Miller Professor Michelle M. Wander ABSTRACT Soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] averages approximately 40% protein and 20% oil and is one of the world’s most important crops. Production of the crop is increasing, especially in less developed countries. Occurrence of diseases and pests affecting soybean have increased as production has expanded from its origin in China to almost 100 countries in 2019. Constraints to production due to diseases and pests have been estimated by FAO to reduce yield by 20 to 40% worldwide. Sudden death syndrome of soybean, soybean rust, and infection by soybean cyst nematode caused by fungal pathogens Fusarium virguliForme and Phakopsora pachyrhizi and the plant-parasitic nematode Heterodera glycines, respectively, are three major yield-limiting problems. Soybean cultivars have a narrow genetic base due to bottlenecks in modern cultivar development. Lack of partially resistant cultivars, in the case of sudden death syndrome, and lack of durable genetic resistance to organisms that have high genetic variability, in the case of soybean rust and cyst nematode, demand efforts to find, understand, and incorporate new sources of resistance into soybean germplasm. The USDA-ARS Soybean Germplasm Collection at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign maintains 20,099 soybean accessions, 10,144 of which have not been evaluated for reaction to F. -

Palatability of Plants to Camels (DBIRD NT)

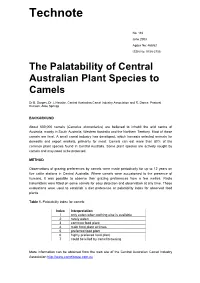

Technote No. 116 June 2003 Agdex No: 468/62 ISSN No: 0158-2755 The Palatability of Central Australian Plant Species to Camels Dr B. Dorges, Dr J. Heucke, Central Australian Camel Industry Association and R. Dance, Pastoral Division, Alice Springs BACKGROUND About 600,000 camels (Camelus dromedarius) are believed to inhabit the arid centre of Australia, mainly in South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory. Most of these camels are feral. A small camel industry has developed, which harvests selected animals for domestic and export markets, primarily for meat. Camels can eat more than 80% of the common plant species found in Central Australia. Some plant species are actively sought by camels and may need to be protected. METHOD Observations of grazing preferences by camels were made periodically for up to 12 years on five cattle stations in Central Australia. Where camels were accustomed to the presence of humans, it was possible to observe their grazing preferences from a few metres. Radio transmitters were fitted on some camels for easy detection and observation at any time. These evaluations were used to establish a diet preference or palatability index for observed food plants. Table 1. Palatability index for camels Index Interpretation 1 only eaten when nothing else is available 2 rarely eaten 3 common food plant 4 main food plant at times 5 preferred food plant 6 highly preferred food plant 7 could be killed by camel browsing More information can be obtained from the web site of the Central Australian Camel Industry Association http://www.camelsaust.com.au 2 RESULTS Table 2. -

ITS Non-Concerted Evolution and Rampant Hybridization in the Legume Genus Lespedeza

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN ITS non-concerted evolution and rampant hybridization in the legume genus Lespedeza Received: 15 August 2016 Accepted: 30 November 2016 (Fabaceae) Published: 04 January 2017 Bo Xu1, Xiao-Mao Zeng1, Xin-Fen Gao1, Dong-Pil Jin2 & Li-Bing Zhang3 The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) as one part of nuclear ribosomal DNA is one of the most extensively sequenced molecular markers in plant systematics. The ITS repeats generally exhibit high-level within-individual homogeneity, while relatively small-scale polymorphism of ITS copies within individuals has often been reported in literature. Here, we identified large-scale polymorphism of ITS copies within individuals in the legume genus Lespedeza (Fabaceae). Divergent paralogs of ITS sequences, including putative pseudogenes, recombinants, and multiple functional ITS copies were sometimes detected in the same individual. Thirty-seven ITS pseudogenes could be easily detected according to nucleotide changes in conserved 5.8S motives, the significantly lower GC contents in at least one of three regions, and the lost ability of 5.8S rDNA sequence to fold into a conserved secondary structure. The distribution patterns of the putative functional clones were highly different between the traditionally recognized two subgenera, suggesting different rates of concerted evolution in two subgenera which could be attributable to their different extents/frequencies of hybridization, confirmed by our analysis of the single-copy nuclear gene PGK. These findings have significant implications in using ITS marker for reconstructing phylogeny and studying hybridization. Concerted evolution is a form of multigene family evolution in which all the tendency of the different genes in a gene family or cluster are assumed to evolve as a unit in concert1,2. -

RESPONSE of SOYABEAN (Glycine Max.L.)

RESPONSE OF SOYABEAN (Glycine max.L.) TO HIGH LEVELS OF ALUMINIUM IN THE SOIL BY PATRICIA MUTALE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF ZAMBIA IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEGREE IN PLANT BREEDING AND SEED SYSTEMS University of Zambia Great East Road Campus Lusaka 2013 DECLARATION I, Patricia Mutale, declare that this dissertation represents my own work and that it has not been previously submitted for a Degree, Diploma or any other qualification at this or any other University. Signature:……………………………………….. Date:…………………………………………… ii APPROVAL This dissertation of Patricia Mutale has been approved by the University of Zambia as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Science in Plant Breeding and Seed Systems Name Signature Date Dr. Mataa …….……………. …....……….. Prof. O.I Lungu ………………..… ……………... Dr. L. Tembo .………………… ……………… iii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my adorable daughters Choolwe and Mapalo, and my lovely husband Chimuka Leo Haamukwanza. iv ABSTRACT Soyabean, Glycine max.L, is the most important oil crop in the Temperate and Sub-tropical regions. The grain consists of twenty percent oil, which makes it the most important crop for producing edible oil. Soyabean is sensitive to high levels of aluminium in the soil, a situation which limits its production. High rainfall areas of Zambia are characterized by acid soils. This study evaluated twenty varieties of soyabean from different seed companies, both in the laboratory and field. The laboratory experiment was done at the University of Zambia, School of Agricultural Sciences. The field experiment was done in the 2012/13 season at Seedco Lusaka West Farm and Liempe Farm. -

Comparison of Seed and Ovule Development in Representative Taxa of the Tribe Cercideae (Caesalpinioideae, Leguminosae) Seanna Reilly Rugenstein Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1983 Comparison of seed and ovule development in representative taxa of the tribe Cercideae (Caesalpinioideae, Leguminosae) Seanna Reilly Rugenstein Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Rugenstein, Seanna Reilly, "Comparison of seed and ovule development in representative taxa of the tribe Cercideae (Caesalpinioideae, Leguminosae) " (1983). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 8435. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/8435 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2.