Proceedings, the 57Th Annual Meeting, 1981

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FIVE CHALLENGES and SOLUTIONS in ONLINE MUSIC TEACHER EDUCATION Page 1 of 10

FIVE CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS IN ONLINE MUSIC TEACHER EDUCATION Page 1 of 10 Volume 5, No. 1 September 2007 FIVE CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS IN ONLINE MUSIC TEACHER EDUCATION David G. Hebert Boston University [email protected] “Nearly 600 graduate students?”1 As remarkable as it may sound, that is the projected student population for the online graduate programs in music education at Boston University School of Music by the end of 2007. With the rapid proliferation of online courses among mainstream universities in recent years, it is likely that more online music education programs will continue to emerge in the near future, which begs the question of what effects this new development will have on the profession. Can online education truly be of the same quality as a traditional face-to-face program? How is it possible to effectively manage such large programs, particularly at the doctoral level? For some experienced music educators, it may be quite difficult to set aside firmly entrenched reservations and objectively consider the new possibilities for teaching and research afforded by recent technology. Yet the future is already here, and nearly 600 music educators have seized the opportunity. Through online programs, the internet has become the latest tool for offering professional development to practicing educators who otherwise would not have access, particularly those currently engaged in full-time employment or residing in rural areas. Recognizing the new opportunities afforded by recent technological developments, Director of the Boston University School of Music, Professor Andre De Quadros and colleagues launched the nation’s first online doctoral program in music education in 2005. -

The Wedding of Kevin Roon & Simon Yates Saturday, the Third of October

The wedding of Kevin Roon & Simon Yates Saturday, the third of October, two thousand and nine Main Lounge The Dartmouth Club at the Yale Club New York City Introductory Music Natasha Paremski & Richard Dowling, piano Alisdair Hogarth & Malcolm Martineau, piano Welcome David Beatty The Man I Love music by George Gershwin (1898–1937) arranged for piano by Earl Wild (b. 1915) Richard Dowling, piano O Tell Me the Truth About Love W. H. Auden (1907–1973) Catherine Cooper I Could Have Danced All Night from My Fair Lady music by Frederick Loewe (1901–1988) lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner (1918–1986) Elizabeth Yates, soprano Simon Yates, piano Sonnet 116 William Shakespeare (1564–1616) Lilla Grindlay Allemande from the Partita No.4 in D major, BWV 828 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) Jeremy Denk, piano Prayer of St. Francis of Assisi Eileen Roon from Liebeslieder Op. 52 Johannes Brahms (1833–1897) text by Georg Friedrich Daumer (1800–1875) translations © by Emily Ezust Joyce McCoy, soprano Jennifer Johnston, mezzo-soprano Matthew Plenk, tenor Eric Downs, bass-baritone Alisdair Hogarth & Malcolm Martineau, piano number 8 Wenn so lind dein Auge mir When your eyes so gently und so lieblich schauet, and so fondly gaze on me, jede letzte Trübe flieht, every last sorrow flees welche mich umgrauet. that once had troubled me. Dieser Liebe schöne Glut, This beautiful glow of our love, lass sie nicht verstieben! do not let it die! Nimmer wird, wie ich, Never will another love you so treu dich ein Andrer lieben. as faithfully as I. number 9 Am Donaustrande On the banks of the Danube, da steht ein Haus, there stands a house, da schaut ein rosiges and looking out of it Mädchen aus. -

Thursday, February 25, at 6:30 Pm. Italian Dinner for Purim, Orde

HONORING TRADITIONS ENGAGING FAMILIES SUPPORTING COMMUNITIES Volume 93, No. 8 • February 2021 • Shevat/Adar 5781 Purim is coming! From Rabbi Thursday, February 25, at 6:30 pm. Jessica “Grease” Megillah Reading and Spiel: 6:30 pm Barolsky All Romemu families are strongly encouraged to join us on Zoom. On its surface, Purim is about the triumph of Italian Dinner for Purim, good over evil, the Order Dinner from epitome of “they tried to kill us, we won, let’s Hamantasch-a-thon Lou Malnati's Pizzeria eat.” In the Purim story, the good guys A Purim Fundraiser Wednesday, February 24 win and the bad guys lose big. For more information please see page 5. Order enough to have some on The fascinating parts of Purim, though, Wednesday night after the Purim Drive are the ones hidden below the surface: Purim Drive-Thru! Thru at CEEBJ and some to enjoy Thursday Vashti as a feminist icon; a story whose night, February 25 before the Purim Shpiel details go—thankfully—way over the Wednesday, February 24, at 6:30 pm. Invite your friends to do the heads of children; a king who is more of 4:30-6:30 pm same, even if they don’t celebrate Purim. a caricature than a leader; real questions A portion of all non-alcoholic purchases about Jewish identity and fitting in. We Join us on Wednesday afternoon, pre-tax go to support Romemu and learn that Purim is a holiday where every - February 24, any time between Lifelong Learning at CEEBJ. thing is turned upside down and back - 4:30-6:30 pm for a Purim Drive-Thru. -

An Introduction to Music Studies Pdf, Epub, Ebook

AN INTRODUCTION TO MUSIC STUDIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jim Samson,J. P. E. Harper-Scott | 310 pages | 31 Jan 2009 | CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS | 9780521603805 | English | Cambridge, United Kingdom An Introduction to Music Studies PDF Book To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. An analysis of sociomusicology, its issues; and the music and society in Hong Kong. Critical Entertainments: Music Old and New. Other Editions 6. The examination measures knowledge of facts and terminology, an understanding of concepts and forms related to music theory for example: pitch, dynamics, rhythm, melody , types of voices, instruments, and ensembles, characteristics, forms, and representative composers from the Middle Ages to the present, elements of contemporary and non-Western music, and the ability to apply this knowledge and understanding in audio excerpts from musical compositions. An Introduction to Music Studies by J. She has been described by the Harvard Gazette as "one of the world's most accomplished and admired music historians". The job market for tenure track professor positions is very competitive. You should have a passion for music and a strong interest in developing your understanding of music and ability to create it. D is the standard minimum credential for tenure track professor positions. Historical studies of music are for example concerned with a composer's life and works, the developments of styles and genres, e. Mus or a B. For other uses, see Musicology disambiguation. More Details Refresh and try again. Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. These models were established not only in the field of physical anthropology , but also cultural anthropology. -

In This Issue

FALL 2019 IN THIS ISSUE JONATHAN BISS CELEBRATING BEETHOVEN: PART I November 5 DANISH STRING QUARTET November 7 PILOBOLUS COME TO YOUR SENSES November 14–16 GABRIEL KAHANE November 23 MFA IN Fall 2019 | Volume 16, No. 2 ARTS LEADERSHIP FEATURE In This Issue Feature 3 ‘Indecent,’ or What it Means to Create Queer Jewish Theatre in Seattle Dialogue 9 Meet the Host of Tiny Tots Concert Series 13 We’re Celebrating 50 Years Empowering a new wave of Arts, Culture and Community of socially responsible Intermission Brain arts professionals Transmission 12 Test yourself with our Online and in-person trivia quiz! information sessions Upcoming Events seattleu.edu/artsleaderhip/graduate 15 Fall 2019 PAUL HEPPNER President Encore Stages is an Encore arts MIKE HATHAWAY Senior Vice President program that features stories Encore Ad 8-27-19.indd 1 8/27/19 1:42 PM KAJSA PUCKETT Vice President, about our local arts community Sales & Marketing alongside information about GENAY GENEREUX Accounting & performances. Encore Stages is Office Manager a publication of Encore Media Production Group. We also publish specialty SUSAN PETERSON Vice President, Production publications, including the SIFF JENNIFER SUGDEN Assistant Production Guide and Catalog, Official Seattle Manager ANA ALVIRA, STEVIE VANBRONKHORST Pride Guide, and the Seafair Production Artists and Graphic Designers Commemorative Magazine. Learn more at encorespotlight.com. Sales MARILYN KALLINS, TERRI REED Encore Stages features the San Francisco/Bay Area Account Executives BRIEANNA HANSEN, AMELIA HEPPNER, following organizations: ANN MANNING Seattle Area Account Executives CAROL YIP Sales Coordinator Marketing SHAUN SWICK Senior Designer & Digital Lead CIARA CAYA Marketing Coordinator Encore Media Group 425 North 85th Street • Seattle, WA 98103 800.308.2898 • 206.443.0445 [email protected] encoremediagroup.com Encore Arts Programs and Encore Stages are published monthly by Encore Media Group to serve musical and theatrical events in the Puget Sound and San Francisco Bay Areas. -

Automated and Modular Refinement Reasoning for Concurrent Programs

Automated and modular refinement reasoning for concurrent programs Chris Hawblitzel Erez Petrank Shaz Qadeer Serdar Tasiran Microsoft Technion Microsoft Ko¸cUniversity Abstract notable successes using the refinement approach in- clude the work of Abrial et al. [2] and the proof of full We present civl, a language and verifier for concur- functional correctness of the seL4 microkernel [37]. rent programs based on automated and modular re- This paper presents the first general and automated finement reasoning. civl supports reasoning about proof system for refinement verification of shared- a concurrent program at many levels of abstraction. memory multithreaded software. Atomic actions in a high-level description are refined We present our verification approach in the context to fine-grain and optimized lower-level implementa- of civl, an idealized concurrent programming lan- tions. A novel combination of automata theoretic guage. In civl, a program is described as a collection and logic-based checks is used to verify refinement. of procedures whose implementation can use the stan- Modular specifications and proof annotations, such dard features such as assignment, conditionals, loops, as location invariants and procedure pre- and post- procedure calls, and thread creation. Each procedure conditions, are specified separately, independently at accesses shared global variables only through invoca- each level in terms of the variables visible at that tions of atomic actions. A subset of the atomic ac- level. We have implemented as an extension to civl tions may be refined by new procedures and a new the language and verifier. We have used boogie civl program is obtained by replacing the invocation of an to refine a realistic concurrent garbage collection al- atomic action by a call to the corresponding proce- gorithm from a simple high-level specification down dure refining the action. -

Elements of Sociology of Music in Today's Historical

AD ALTA JOURNAL OF INTERDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH ELEMENTS OF SOCIOLOGY OF MUSIC IN TODAY’S HISTORICAL MUSICOLOGY AND MUSIC ANALYSIS aKAROLINA KIZIŃSKA national identity, and is not limited to ethnographic methods. Rather, sociomusicologists use a wide range of research methods Adam Mickiewicz University, ul. Szamarzewskiego 89A Poznań, and take a strong interest in observable behavior and musical Poland interactions within the constraints of social structure. e-mail: [email protected] Sociomusicologists are more likely than ethnomusicologists to make use of surveys and economic data, for example, and tend to focus on musical practices in contemporary industrialized Abstract: In this article I try to show the incorporation of the elements of sociology of 6 societies”. Classical musicology, and it’s way of emphasizing music by such disciplines as historical musicology and music analysis. For that explain how sociology of music is understood, and how it is connected to critical historiographic and analytical rather than sociological theory, criticism or aesthetic autonomy. I cite some of the musicologists that wrote approaches to research, is the reason why sociomusicology was about doing analysis in context and broadening the research of musicology (e.g. Jim regarded as a small subdiscipline for a long time. But the Samson, Joseph Kerman). I also present examples of the inclusion of sociology of music into historical musicology and music analysis – the approach of Richard increasing popularity of ethnomusicology and new musicology Taruskin in and Suzanne Cusick. The aim was to clarify some of the recent changes in (as well as the emergence of interdisciplinary field of cultural writing about music, that seem to be closer today to cultural studies than classical studies), created a situation in which sociomusicology is not only musicology. -

View PDF Online

MARLBORO MUSIC 60th AnniversAry reflections on MA rlboro Music 85316_Watkins.indd 1 6/24/11 12:45 PM 60th ANNIVERSARY 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC Richard Goode & Mitsuko Uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 2 6/23/11 10:24 AM 60th AnniversA ry 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC richard Goode & Mitsuko uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 3 6/23/11 9:48 AM On a VermOnt HilltOp, a Dream is BOrn Audience outside Dining Hall, 1950s. It was his dream to create a summer musical community where artists—the established and the aspiring— could come together, away from the pressures of their normal professional lives, to exchange ideas, explore iolinist Adolf Busch, who had a thriving music together, and share meals and life experiences as career in Europe as a soloist and chamber music a large musical family. Busch died the following year, Vartist, was one of the few non-Jewish musicians but Serkin, who served as Artistic Director and guiding who spoke out against Hitler. He had left his native spirit until his death in 1991, realized that dream and Germany for Switzerland in 1927, and later, with the created the standards, structure, and environment that outbreak of World War II, moved to the United States. remain his legacy. He eventually settled in Vermont where, together with his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, his brother Herman Marlboro continues to thrive under the leadership Busch, and the great French flutist Marcel Moyse— of Mitsuko Uchida and Richard Goode, Co-Artistic and Moyse’s son Louis, and daughter-in-law Blanche— Directors for the last 12 years, remaining true to Busch founded the Marlboro Music School & Festival its core ideals while incorporating their fresh ideas in 1951. -

Toward a New Comparative Musicology

Analytical Approaches To World Music 2.2 (2013) 148-197 Toward a New Comparative Musicology Patrick E. Savage1 and Steven Brown2 1Department of Musicology, Tokyo University of the Arts 2Department of Psychology, Neuroscience & Behaviour, McMaster University We propose a return to the forgotten agenda of comparative musicology, one that is updated with the paradigms of modern evolutionary theory and scientific methodology. Ever since the field of comparative musicology became redefined as ethnomusicology in the mid-20th century, its original research agenda has been all but abandoned by musicologists, not least the overarching goal of cross-cultural musical comparison. We outline here five major themes that underlie the re-establishment of comparative musicology: (1) classification, (2) cultural evolution, (3) human history, (4) universals, and (5) biological evolution. Throughout the article, we clarify key ideological, methodological and terminological objections that have been levied against musical comparison. Ultimately, we argue for an inclusive, constructive, and multidisciplinary field that analyzes the world’s musical diversity, from the broadest of generalities to the most culture-specific particulars, with the aim of synthesizing the full range of theoretical perspectives and research methodologies available. Keywords: music, comparative musicology, ethnomusicology, classification, cultural evolution, human history, universals, biological evolution This is a single-spaced version of the article. The official version with page numbers 148-197 can be viewed at http://aawmjournal.com/articles/2013b/Savage_Brown_AAWM_Vol_2_2.pdf. omparative musicology is the academic comparative musicology and its modern-day discipline devoted to the comparative study successor, ethnomusicology, is too complex to of music. It looks at music (broadly defined) review here. -

I:\My Drive\Mailing Labels\Mailing Labels

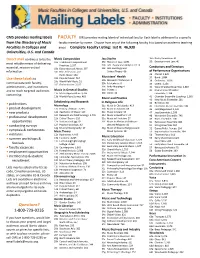

CMS provides mailing labels FACULTY CMS provides mailing labels of individual faculty. Each label is addressed to a specific from the Directory of Music faculty member by name. Choose from any of the following faculty lists based on academic teaching Faculties in Colleges and areas. Complete Faculty Listing: List B: 46,930 Universities, U.S. and Canada. Direct mail continues to be the Music Composition Jazz Studies 35h Radio/Television: 43 10a Traditional Compositional 29a History of Jazz: 1,694 35i Entertainment Law: 40 most reliable means of delivering 29b Jazz Theory and Analysis: 2, Practices: 2,397 114 Conductors and Directors essential, mission‐critical 10b Electroacoustic Music: 397 29c Jazz Sociology and information. 10c Film, Television, and Critical Theory: 66 of Performance Organizations Radio Music: 2 36 Choral: 2,528 80 Musicians' Health 10d Popular Music: 454 37 Band: 1,884 Use these labels to 30a Alexander Technique: 10e World Folk Music: 51 8 38 Orchestra: 1,036 communicate with faculty, 30b Feldenkrais: 0 10f Orchestration: 2,037 39 Opera: 1,259 administrators, and institutions 30c Body Mapping: 0 40 Vocal Chamber Ensemble: 1,084 and to reach targeted audiences Music in General Studies 30d Pilates: 1 41 Instrumental Chamber 30e Other: 10 concerning: 11a Music Appreciation: 3,765 Ensemble: 1,398 11b World Music Survey: 42 Chamber Ensemble Coaching: 1,3 463 Music and Practice 65 43 New Music Ensemble: 261 Scholarship and Research • publications in Religious Life 44 Bell Choir: 86 Musicology 31a Music in Christianity: 413 -

Utopian Ecomusicologies and Musicking Hornby Island

WHAT IS MUSIC FOR?: UTOPIAN ECOMUSICOLOGIES AND MUSICKING HORNBY ISLAND ANDREW MARK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, CANADA August, 2015 © Andrew Mark 2015 Abstract This dissertation concerns making music as a utopian ecological practice, skill, or method of associative communication where participants temporarily move towards idealized relationships between themselves and their environment. Live music making can bring people together in the collective present, creating limited states of unification. We are “taken” by music when utopia is performed and brought to the present. From rehearsal to rehearsal, band to band, year to year, musicking binds entire communities more closely together. I locate strategies for community solidarity like turn-taking, trust-building, gift-exchange, communication, fundraising, partying, education, and conflict resolution as plentiful within musical ensembles in any socially environmentally conscious community. Based upon 10 months of fieldwork and 40 extended interviews, my theoretical assertions are grounded in immersive ethnographic research on Hornby Island, a 12-square-mile Gulf Island between mainland British Columbia and Vancouver Island, Canada. I describe how roughly 1000 Islanders struggle to achieve environmental resilience in a uniquely biodiverse region where fisheries collapsed, logging declined, and second-generation settler farms were replaced with vacation homes in the 20th century. Today, extreme gentrification complicates housing for the island’s vulnerable populations as more than half of island residents live below the poverty line. With demographics that reflect a median age of 62, young individuals, families, and children are squeezed out of the community, unable to reproduce Hornby’s alternative society. -

Camera Lucida Symphony, Among Others

Pianist REIKO UCHIDA enjoys an active career as a soloist and chamber musician. She performs Taiwanese-American violist CHE-YEN CHEN is the newly appointed Professor of Viola at regularly throughout the United States, Asia, and Europe, in venues including Suntory Hall, the University of California, Los Angeles Herb Alpert School of Music. He is a founding Avery Fisher Hall, Alice Tully Hall, the 92nd Street Y, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, member of the Formosa Quartet, recipient of the First-Prize and Amadeus Prize winner the Kennedy Center, and the White House. First prize winner of the Joanna Hodges Piano of the 10th London International String Quartet Competition. Since winning First-Prize Competition and Zinetti International Competition, she has appeared as a soloist with the in the 2003 Primrose Competition and “President Prize” in the Lionel Tertis Competition, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Santa Fe Symphony, Greenwich Symphony, and the Princeton Chen has been described by San Diego Union Tribune as an artist whose “most impressive camera lucida Symphony, among others. She made her New York solo debut in 2001 at Weill Hall under the aspect of his playing was his ability to find not just the subtle emotion, but the humanity Sam B. Ersan, Founding Sponsor auspices of the Abby Whiteside Foundation. As a chamber musician she has performed at the hidden in the music.” Having served as the principal violist of the San Diego Symphony for Chamber Music Concerts at UC San Diego Marlboro, Santa Fe, Tanglewood, and Spoleto Music Festivals; as guest artist with Camera eight seasons, he is the principal violist of the Mainly Mozart Festival Orchestra, and has Lucida, American Chamber Players, and the Borromeo, Talich, Daedalus, St.