What Is Mahayana Buddhism ?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art

Rienjang and Stewart (eds) Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art Edited by Wannaporn Rienjang Peter Stewart Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art Since the beginning of Gandhāran studies in the nineteenth century, chronology has been one of the most significant challenges to the understanding of Gandhāran art. Many other ancient societies, including those of Greece and Rome, have left a wealth of textual sources which have put their fundamental chronological frameworks beyond doubt. In the absence of such sources on a similar scale, even the historical eras cited on inscribed Gandhāran works of art have been hard to place. Few sculptures have such inscriptions and the majority lack any record of find-spot or even general provenance. Those known to have been found at particular sites were sometimes moved and reused in antiquity. Consequently, the provisional dates assigned to extant Gandhāran sculptures have sometimes differed by centuries, while the narrative of artistic development remains doubtful and inconsistent. Building upon the most recent, cross-disciplinary research, debate and excavation, this volume reinforces a new consensus about the chronology of Gandhāra, bringing the history of Gandhāran art into sharper focus than ever. By considering this tradition in its wider context, alongside contemporary Indian art and subsequent developments in Central Asia, the authors also open up fresh questions and problems which a new phase of research will need to address. Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art is the first publication of the Gandhāra Connections project at the University of Oxford’s Classical Art Research Centre, which has been supported by the Bagri Foundation and the Neil Kreitman Foundation. -

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

The Development of Prajna in Buddhism from Early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita System: with Special Reference to the Sarvastivada Tradition

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 2001 The development of Prajna in Buddhism from early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita system: with special reference to the Sarvastivada tradition Qing, Fa Qing, F. (2001). The development of Prajna in Buddhism from early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita system: with special reference to the Sarvastivada tradition (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/15801 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/40730 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Dcvelopmcn~of PrajfiO in Buddhism From Early Buddhism lo the Praj~iBpU'ranmirOSystem: With Special Reference to the Sarv&tivada Tradition Fa Qing A DISSERTATION SUBMIWED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES CALGARY. ALBERTA MARCI-I. 2001 0 Fa Qing 2001 1,+ 1 14~~a",lllbraly Bibliolheque nationale du Canada Ac uisitions and Acquisitions el ~ibqio~raphiiSetvices services bibliogmphiques The author has granted anon- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pernettant a la National Library of Canada to Eiblioth&quenationale du Canada de reproduce, loao, distribute or sell reproduire, priter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. -

On the Penetration of Dharmakya and Dharmadesana -Based on the Different Ideas of Dharani and Tathagatagarbha

On the Penetration of Dharmakya and Dharmadesana -based on the different ideas of dharani and tathagatagarbha- Kakusho U jike We can recognize many developements of the Buddhakaya theory in the evo- lution of Mahayana thought systems which are related to various doctrines such as the Vi jnanavada, etc. In my opinion, the Buddhakaya theory stressed how the Bodhisattvas or any living being can meet the eternal Buddha and enjoy the benefits of instruction on enlightenment from him. In the Mahayana, the concept of truth also developed parallel with the Bud- dhakaya theory and the most important theme for the Mahayanist is how to understand the nature of the Buddha who became one with the truth (dharma- kaya). That is to say, the problem of how to realize the truth is the same pro- blem of how to meet the eternal Buddha with the joy of uniting oneself with the realm of the Buddha's enlightenment (dharmadhatu). In this situation one's faculties are always tested in the effort to encounter and understand the real teaching of the Buddha, because the truth revealed by the Buddha is quite high and deep, going beyond the intellect of ordinary people The Buddha's teaching is understood only by eminent Bodhisattvas who possess the super power of hearing the subtle voice of the Buddha. One of the excellent means of the Bodhisattvas for hearing, memorizing, and preaching etc., the teachings of the Buddha is considered to be the dharani. Dharani seemed to appear at first in the Prajnaparamita-sutras or in other Sutras having close relation to theme). -

The Buddhist Conception of Reality

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE The Buddhist Conception of Reality Daisetz T. Suzuki There is one question every earnest-minded man will ask as soon as he grows old, or rather, young enough to reason about things, and that is: “Why are we here?” or “What is the significance of life here?” The question may not always take this form; it will vary according to the surroundings and circum stances in which the questioner may happen to find himself. Once up to the horizon of consciousness, this question is quite a stubborn one and will not stop disturbing one’s peace of mind. It will insist on getting a satisfactory answer one way or another. This inquiry after the significance or value of life is no idle one, and no verbal quibble will gratify the inquirer for he is ready to give his life for it. We fre quently hear in Japan of young men committing suicide, despairing at their inability to solve the question. While this is a hasty and in a way cowardly deed, they are so upset that they do not know what they are doing; they are altogether beside themselves. This questioning about the significance of life is tantamount to seeking after ultimate reality. Ultimate reality may sound to some people too philosophical and they may regard it as of no concern to them. They may regard it outside their domain of interest, and the subject I am going to speak about tonight is liable to be put aside as belonging to the professional business of a class of peo ple known as philosophers. -

VT Module6 Lineage Text Major Schools of Tibetan Buddhism

THE MAJOR SCHOOLS OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM By Pema Khandro A BIRD’S EYE VIEW 1. NYINGMA LINEAGE a. Pema Khandro’s lineage. Literally means: ancient school or old school. Nyingmapas rely on the old tantras or the original interpretation of Tantra as it was given from Padmasambhava. b. Founded in 8th century by Padmasambhava, an Indian Yogi who synthesized the teachings of the Indian MahaSiddhas, the Buddhist Tantras, and Dzogchen. He gave this teaching (known as Vajrayana) in Tibet. c. Systemizes Buddhist philosophy and practice into 9 Yanas. The Inner Tantras (what Pema Khandro Rinpoche teaches primarily) are the last three. d. It is not a centralized hierarchy like the Sarma (new translation schools), which have a figure head similar to the Pope. Instead, the Nyingma tradition is de-centralized, with every Lama is the head of their own sangha. There are many different lineages within the Nyingma. e. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is the emphasis in the Tibetan Yogi tradition – the Ngakpa tradition. However, once the Sarma translations set the tone for monasticism in Tibet, the Nyingmas also developed a monastic and institutionalized segment of the tradition. But many Nyingmas are Ngakpas or non-monastic practitioners. f. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is that it is characterized by treasure revelations (gterma). These are visionary revelations of updated communications of the Vajrayana teachings. Ultimately treasure revelations are the same dharma principles but spoken in new ways, at new times and new places to new people. Because of these each treasure tradition is unique, this is the major reason behind the diversity within the Nyingma. -

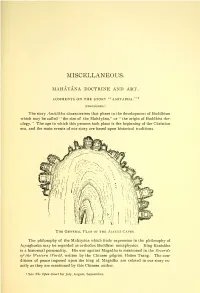

The Mahayana Doctrine and Art. Comments on the Story of Amitabha

MISCEIvIvANEOUS. MAHAYANA DOCTRINE AND ART. COMMENTS ON THE STORY "AMITABHA."^ (concluded.) The story Amitabha characterises that phase in the development of Buddhism which may be called " the rise of the Mahayana," or " the origin of Buddhist the- ology." The age in which this process took place is the beginning of the Christian era, and the main events of our story are based upon historical traditions. The General Plan of the Ajant.v Caves. The philosophy of the Mahayana which finds expression in the philosophy of Acvaghosha may be regarded as orthodox Buddhist metaphysics. King Kanishka is a historical personality. His war against Magadha is mentioned in the Records of the Western IVorld, written by the Chinese pilgrim Hsiien Tsang. The con- ditions of peace imposed upon the king of Magadha are related in our story ex- actly as they are mentioned by this Chinese author. 1 See The Open Court for July, August, September. 622 THE OPEN COURT. The monastic life described in the first, second, and fifth chapters of the story Amitdbha is a faithful portrayal of the historical conditions of the age. The ad- mission and ordination of monks (in Pali called Pabbajja and Upasampada) and the confession ceremony (in Pfili called Uposatha) are based upon accounts of the MahSvagga, the former in the first, the latter in the second, Khandaka (cf. Sacred Books of the East, Vol. XIII.). A Mother Leading Her Child to Buddha. (Ajanta caves.) Kevaddha's humorous story of Brahma (as told in The Open Cozirt, No. 554. pp. 423-427) is an abbreviated account of an ancient Pali text. -

B U Ddhis T S Tu Dies To

BUDDHIST STUDIES TODAY UNIVERSITY OF UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA BRITISH COLUMBIA JULY 7-9, 2015 Symposium Proceedings A three-day symposium to celebrate the first Dissertation Fellows of The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Program in Buddhist Studies. The event is sponsored by The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation, organized by the American Council of Learned Societies, and hosted by the University of British Columbia. Buddhist Studies Today Convocation – Tuesday Evening Introductory remarks by representatives of the University of British Columbia, The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation, and the American Council of Learned Societies, followed by a keynote address by A symposium to celebrate the first Dissertation Fellows of Professor Donald Lopez The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Program in Buddhist Studies Fellows’ Workshop – Wednesday and Thursday Presentations of work in progress by Dissertation Fellows. Fellows, members of the advisory committee, and invited discussants will University of British Columbia explore the potential synergies in fellows’ projects and their implications for the developing field of Buddhist studies worldwide July 7–9, 2015 Assessing the State of the Field of Buddhist Studies – Thursday Roundtable of program advisers to highlight themes that emerged from placing the research interests of the fellows in conversation with each other Special thanks to the University of British Columbia for hosting the Symposium Tuesday Speakers 5:30— RECEPTION ON THE TERRACE 6:00pm Sage Bistro—East Side Arvind Gupta is the thirteenth President and Vice-Chancellor CONVOCATION of the University of British Columbia (UBC), a position he has 6:00— held since July 1, 2014. -

Proquest Dissertations

Daoxuan's vision of Jetavana: Imagining a utopian monastery in early Tang Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Tan, Ai-Choo Zhi-Hui Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 09:09:41 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280212 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are In typewriter face, while others may be from any type of connputer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 DAOXUAN'S VISION OF JETAVANA: IMAGINING A UTOPIAN MONASTERY IN EARLY TANG by Zhihui Tan Copyright © Zhihui Tan 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2002 UMI Number: 3073263 Copyright 2002 by Tan, Zhihui Ai-Choo All rights reserved. -

The Kayas / Bodies of a Buddha

The Kayas / Bodies of a Buddha The original meaning of the Sanskrit word Kaya (Tibetan: sku/ku) is 'that which is accumulated'. In English Kaya is translated as 'body'. However, the Kayas of Buddhas do not literally refer only to the form aggregates of Buddhas but also to Buddhas themselves, to their various attributes, and so forth. There are different ways to categorize Kayas: 1. The category into five Kayas 2. The category into four Kayas 3. The category into three Kayas 4. The category into two Kayas 1. The category into five Kayas The category into five Kayas refers to: I. The Dharmakaya / Truth Body (chos sku / choe ku) II. The Svabhavakaya / Nature Body (ngo bo nyid sku / ngo wo nyi ku) III. The Jnanakaya / Wisdom Truth Body (ye shes chos sku / ye she choe ku) IV. The Sambhogakaya / Enjoyment Body (longs sku / long ku) V. The Nimanakaya / Emanation Body (sprul sku / truel ku) Here the basis of the category is Kaya, which means that Kaya is categorized or classified into the five Kayas. I. The Dharmakaya / Truth Body Kaya and Dharmakaya are synonymous. Whatever is a Kaya is necessarily a Dharmakaya and vice versa. The definition of a Dharmakaya is: a final Kaya that is attained in dependence on meditating on its attaining agents, the three exalted knowers. The three exalted knowers are: a) Knower of basis (the Arya paths in the continua of Hearers and Solitary Realizers) b) Knower of paths (the Arya paths in the continua of Buddhas and of Bodhisattvas who have reached the Mahayana path of seeing or the Mahayana path of meditation) c) Exalted knower of aspects (the Arya paths, that is, omniscient mental consciousnesses, in the continua of Buddhas) II. -

The Depth Psychology of the Yogacara

Aspects of Buddhist Psychology Lecture 42: The Depth Psychology of the Yogacara Reverend Sir, and Friends Our course of lectures week by week is proceeding. We have dealt already with the analytical psychology of the Abhidharma; we have dealt also with the psychology of spiritual development. The first lecture, we may say, was concerned mainly with some of the more important themes and technicalities of early Buddhist psychology. We shall, incidentally, be referring back to some of that material more than once in the course of the coming lectures. The second lecture in the course, on the psychology of spiritual development, was concerned much more directly than the first lecture was with the spiritual life. You may remember that we traced the ascent of humanity up the stages of the spiral from the round of existence, from Samsara, even to Nirvana. Today we come to our third lecture, our third subject, which is the Depth Psychology of the Yogacara. This evening we are concerned to some extent with psychological themes and technicalities, as we were in the first lecture, but we're also concerned, as we were in the second lecture, with the spiritual life itself. We are concerned with the first as subordinate to the second, as we shall see in due course. So we may say, broadly speaking, that this evening's lecture follows a sort of middle way, or middle course, between the type of subject matter we had in the first lecture and the type of subject matter we had in the second. Now a question which immediately arises, and which must have occurred to most of you when the title of the lecture was announced, "What is the Yogacara?" I'm sorry that in the course of the lectures we keep on having to have all these Sanskrit and Pali names and titles and so on, but until they become as it were naturalised in English, there's no other way. -

On Doctrinal Similarities Between Sthiramati and Xuanzang

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 29 Number 2 2006 (2008) The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies (ISSN 0193-600XX) is the organ of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Inc. As a peer- reviewed journal, it welcomes scholarly contributions pertaining to EDITORIAL BOARD all facets of Buddhist Studies. JIABS is published twice yearly. KELLNER Birgit Manuscripts should preferably be sub- KRASSER Helmut mitted as e-mail attachments to: Joint Editors [email protected] as one single file, complete with footnotes and references, BUSWELL Robert in two different formats: in PDF-format, and in Rich-Text-Format (RTF) or Open- CHEN Jinhua Document-Format (created e.g. by Open COLLINS Steven Office). COX Collet GÓMEZ Luis O. Address books for review to: HARRISON Paul JIABS Editors, Institut für Kultur - und Geistesgeschichte Asiens, Prinz-Eugen- VON HINÜBER Oskar Strasse 8-10, A-1040 Wien, AUSTRIA JACKSON Roger JAINI Padmanabh S. Address subscription orders and dues, KATSURA Shōryū changes of address, and UO business correspondence K Li-ying (including advertising orders) to: LOPEZ, Jr. Donald S. Dr Jérôme Ducor, IABS Treasurer MACDONALD Alexander Dept of Oriental Languages and Cultures SCHERRER-SCHAUB Cristina Anthropole SEYFORT RUEGG David University of Lausanne CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland SHARF Robert email: [email protected] STEINKELLNER Ernst Web: http://www.iabsinfo.net TILLEMANS Tom Fax: +41 21 692 30 45 Subscriptions to JIABS are USD 40 per year for individuals and USD 70 per year for libraries and other institutions. For informations on membership in IABS, see back cover. Cover: Cristina Scherrer-Schaub Font: “Gandhari Unicode” designed by Andrew Glass (http://andrewglass.org/ fonts.php) © Copyright 2008 by the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Inc.