Book Reviews VII: Journal of the Marion E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Late Scholar

The Late Scholar 99871444760866871444760866 TheThe LateLate ScholarScholar (820h).indd(820h).indd i 009/10/20139/10/2013 115:01:235:01:23 By Jill Paton Walsh The Attenbury Emeralds By Jill Paton Walsh and Dorothy L. Sayers A Presumption of Death By Dorothy L. Sayers and Jill Paton Walsh Thrones, Dominations Imogen Quy detective stories by Jill Paton Walsh The Wyndham Case A Piece of Justice Debts of Dishonour The Bad Quarto Detective stories by Dorothy L. Sayers Busman’s Honeymoon Clouds of Witness The Documents in the Case (with Robert Eustace) Five Red Herrings Gaudy Night Hangman’s Holiday Have His Carcase In the Teeth of the Evidence Lord Peter Views the Body Murder Must Advertise The Nine Tailors Striding Folly Strong Poison Unnatural Death The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club Whose Body? 99871444760866871444760866 TheThe LateLate ScholarScholar (820h).indd(820h).indd iiii 009/10/20139/10/2013 115:01:235:01:23 JILL PATON WALSH The Late Scholar Based on the characters of Dorothy L. Sayers 99871444760866871444760866 TheThe LateLate ScholarScholar (820h).indd(820h).indd iiiiii 009/10/20139/10/2013 115:01:235:01:23 First published in 2013 by Hodder & Stoughton An Hachette UK company 1 Copyright © 2013 by Jill Paton Walsh and the Trustees of Anthony Fleming, deceased The right of Jill Paton Walsh to be identifi ed as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

Jill Paton Walsh (1937 - 2020)

10 VII Jill Paton Walsh (1937 - 2020) Jill Paton Walsh, born Gillian Bliss on April 29, 1937, was a British children’s book author and novelist who added original volumes to Dorothy L. Sayers’s Lord Peter Wimsey mystery series. She died in Cambridge, England, on October 18, 2020, at the age of 83. Jill was born in north London but spent several treasured years of her childhood in St. Ives with her grandparents, where she was sent during The Blitz. Memories from her years in St. Ives, as well as her Catholic upbringing, influenced her later writing. After completing her educa- tion at St. Michael’s Convent in London, Used by permission; © Lesley Simpson, DLS Society. she read English literature at St. Anne’s Jill Paton Walsh at Sayers Society College, Oxford. There, she attended event at Augustine House. lectures given by C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Photographer: Lesley Simpson. Tolkien and was struck by the authors’ commitment to both rigorous scholarship and the delight of fantasy. Jill taught English at Enfield Grammar School but left after marrying Antony Paton Walsh in 1961 and having the couple’s first child. Writing children’s books entertained and fortified her as she struggled through the isolation and challenges of young motherhood. She wrote over twenty-three books for young readers but eventually turned her attention to writing for adults. Jill’s ten adult novels include a four-book detective series featuring amateur sleuth Imogen Quy and set at a fictional college in Cambridge. Jill and her husband, with whom she had three children, were separated from 1986 until his death in 2003. -

Richard C. West (1944-2020)

Remembrances 11 The trustees of the Dorothy L. Sayers estate offered Jill the opportunity to complete Sayers’s last Lord Peter Wimsey novel-in-progress, Thrones, Domi- nations, after the success of Knowledge of Angels. As part of her work on this book, Jill made a research visit to the Wade Center in April 1996 in order to consult a draft version of the novel in the Wade’s manuscript collection. She went on to write three more mysteries featuring Lord Peter and Harriet Vane: A Presumption of Death (2002), The Attenbury Emeralds (2010), and The Late Scholar (2013). Jill was president of the Dorothy L. Sayers Society at the time of her death. In an October 2010 Guardian article she wrote, “Lord Peter … is, in terms of sheer enjoyment, the best company who has ever lived in my inner world.” KENDRA LANGDON JUSKUS Richard C. West (1944-2020) Richard West, longtime Tolkien scholar and friend of the Wade Center, passed away from COVID-19 on November 29, 2020, in Madison, Wisconsin. Richard began the University of Wisconsin- Madison Tolkien Society while a student there in September 1966, and became part of the first wave of early Tolkien scholarship. He would remain an active Tolkien scholar the rest of his life, authoring Tolkien Criticism: An Annotated Checklist (1970), publishing and editing the Tolkien journal and fanzine Orcrist (1966-1977, 2017), becoming a founding member of The Madison Science Fiction Group and helping to found the feminist Used by permission; © Carl F. Hostetter. Used by permission; © Carl F. science fiction convention WisCon, as Richard West in 2019. -

Diplomova Prace.Pdf

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Marcela Nejezchlebová Brezánska Harriet Vane: The “New Young Woman” in Dorothy L. Sayers’s Novels Master‟s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: PhDr. Lidia Kyzlinková, CSc., M.Litt. 2010 1 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. 2 I would like to thank to my supervisor, PhDr. Lidia Kyzlinková, CSs., M.Litt. for her patience, valuable advice and help. I also want to express my thanks for her assistance in recommending some significant sources for the purpose of this thesis. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 5 2. Sayers‟s Background ............................................................................................ 8 2.1 Sayers‟s Life and Work ........................................................................................ 8 2.2 On the Genre ....................................................................................................... 14 2.3 Pro-Feminist and Feminist Attitudes and Writings, Sayers, Wollstonecraft and Others: Towards Education of Women ........................................................ 22 3. Strong Poison ...................................................................................................... 34 3.1 Harriet‟s Rational Approach to Love ................................................................. -

COLIN DURIEZ Dorothy L

A BIOGRAPHY Death, Dante, and Lord Peter Wimsey COLIN DURIEZ Dorothy L. Sayers: A chronology 1713 Great sluice burst at Denver in the Fens (inspiration for the flood in Sayers’The Nine Tailors). 1854 Birth of Henry Sayers, Tittleshall, Norfolk. Son of Revd Robert Sayers. 1879 Opening of Somerville Hall (later renamed Somerville College), Oxford. Henry Sayers obtains a degree in Divinity from Magdalen College, Oxford. 1880 Henry Sayers ordained as minister of the Church of England in Hereford. 1884 Henry Sayers becomes headmaster of the Christ Church Choir School. 1892 Henry Sayers and Helen Mary (“Nell/Nelly”) Leigh marry. 1893 Dorothy Leigh Sayers born on 13 June, in the old Choir House at 1, Brewer Street, Oxford. Christened by Henry Sayers, 15 July, over the road in Christ Church Cathedral. 1894 BA qualifications opened to women in England, but without the award of a university BA degree. 1897 Henry Sayers accepted the living of Bluntisham-cum- Earith in East Anglia as rector. 1906 Dorothy discovers Alexander Dumas’ influentialThe Three Musketeers at the age of thirteen. 1908 On approaching her sixteenth birthday, Dorothy’s parents decided to send her to boarding school. Dorothy is taken to see Shakespeare’s Henry V in London. 178 A chronology 1909 Sent to the Godolphin School in Salisbury, 17 January, as a boarder. 1910 Dorothy pressured into being confirmed as an Anglican at Salisbury Cathedral. 1911 Dorothy comes first in the country in the Cambridge Higher Local Examinations, gaining distinctions in French and Spoken German. Nearly dies from the consequences of measles; sent home to recover. -

Genre and Gender in Selected Works by Detection Club Writers Dorothy L. Sayers and Agatha Christie

SEVENTY YEARS OF SWEARING UPON ERIC THE SKULL: GENRE AND GENDER IN SELECTED WORKS BY DETECTION CLUB WRITERS DOROTHY L. SAYERS AND AGATHA CHRISTIE A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Monica L. Lott May 2013 Dissertation written by Monica L. Lott B.A., The University of Akron, 2003 B.S., The University of Akron, 2003 M.A., The University of Akron, 2005 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2013 Approved by Tammy Clewell Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Vera Camden Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Robert Trogdon Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Maryann DeJulio Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Clare Stacey Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Accepted by Robert Trogdon Chair, English Department Raymond A. Craig Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements.................................................................................... iv Introduction..................................................................................................1 Codification of the Genre.................................................................2 The Gendered Detective in Sayers and Christie ..............................9 Chapter Synopsis............................................................................11 Dorothy L. Sayers, the Great War, and Shell-shock..................................20 Sayers and World War Two in Britain ..........................................24 Shell-shock and Treatment -

Sj.Bdj.2012.1141.Pdf

LETTERS and tattoos. Over several years her lip adolescents and young adults,2 notably Interest declared – the author sought piercing resulted in severe gum erosion tongue and lip piercing. Gum recession advice via her agent on the accuracy at the base of the left first incisor, to the is a recognised and not uncommon com- and feasibility of her dental content. extent that a large amount of the root plication of lip piercing,3 is irreversible M. Bishop, by email became visible and the tooth became and can potentially lead to tooth loss. 1. Paton Walsh J, Sayers D L. The new Lord Peter loose. She removed the lower piercing It has been suggested that gum erosion Wimsey novel: A presumption of death. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2002. after six years for aesthetic reasons, can be reduced by wearing PTFE (surgi- 2. Maynard K. News. Secret service dentist leaves having not been concerned by her gum cal grade plastic) jewellery, rather than legacy. Br Dent J 2012; 213: 101. erosion. On presenting to a general den- metal jewellery, but there is scant pub- DOI: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.1140 tal practitioner she was advised that the lished evidence. Guidance about piercing gum erosion was severe and irrevers- is often from the experience of pierc- A GREAT WASTE ible and to remove the upper piercing, ers or associates. However, there is an Sir, I am writing to inform readers about which had caused moderate erosion increasing body of evidence-based data the current government e-petition set up at the upper left canine. -

Class, Gender and Memory in Golden Age Crime Fiction by Women

‘How Are You Getting on with Your Forgetting?’ – Class, Gender and Memory in Golden Age Crime Fiction by Women Értekezés a doktori (Ph.D.) fokozat megszerzése érdekében az Irodalomtudomány tudományágban Írta: Zsámba Renáta okleveles angol és francia nyelv és irodalom szakos bölcsész és tanár Készült a Debreceni Egyetem Irodalomtudományok doktori iskolája (Angol-amerikai irodalomtudományi programja) keretében Témavezető: Dr. Bényei Tamás ……….………………………………. (olvasható aláírás) A doktori szigorlati bizottság: elnök: Dr. ………………………… tagok: Dr. ………………………… Dr. ………………………… A doktori szigorlat időpontja: 200… . ……………… … . Az értekezés bírálói: Dr. ........................................... Dr. …………………………… Dr. ........................................... A bírálóbizottság: elnök: Dr. ........................................... tagok: Dr. ………………………….. Dr. ………………………….. Dr. ………………………….. Dr. ………………………….. A nyilvános vita időpontja: 20… . ……………… … . 2 „Én Zsámba Renáta teljes felelősségem tudatában kijelentem, hogy a benyújtott értekezés önálló munka, a szerzői jog nemzetközi normáinak tiszteletben tartásával készült, a benne található irodalmi hivatkozások egyértelműek és teljesek. Nem állok doktori fokozat visszavonására irányuló eljárás alatt, illetve 5 éven belül nem vontak vissza tőlem odaítélt doktori fokozatot. Jelen értekezést korábban más intézményben nem nyújtottam be és azt nem utasították el.” 3 Doktori (PhD) Értekezés ‘How Are You Getting on with Your Forgetting?’ – Class, Gender and Memory in Golden Age Crime Fiction by Women Zsámba Renáta -

A Dictionary of Fictional Detectives

Gumshoes: A Dictionary of Fictional Detectives Mitzi M. Burnsdale Greenwood Press GUMSHOES A Dictionary of Fictional Detectives Mitzi M. Brunsdale GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Brunsdale, Mitzi. Gumshoes : a dictionary of fictional detectives / Mitzi M. Brunsdale. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0–313–33331–9 (alk. paper) 1. Detective and mystery stories—Bio-bibliography. 2. Detective and mystery stories—Stories, plots, etc. I. Title. PN3377.5.D4B78 2006 809.3'7209—dc22 2005034853 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright # 2006 by Mitzi M. Brunsdale All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2005034853 ISBN: 0–313–33331–9 First published in 2006 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 For Anne Jones with love and thanks: You made this one possible. CONTENTS List of Entries . ix Preface . xiii How to Use This Book . xvii Introduction: The Ancestry of the Contemporary Series Detective . 1 The Dictionary . 33 Appendix A: Authors and Their Sleuths . 417 Appendix B: Detectives in Their Geographical Areas . 423 Appendix C: Historical Detectives Listed Chronologically . 429 Appendix D: Detectives Listed by Field of Employment . 431 Appendix E: Awards for Mystery and Crime Fiction . -

Empire and Englishness in the Detective Fiction of Dorothy L. Sayers and PD James

The Imperial Detective: Empire and Englishness in the Detective Fiction of Dorothy L. Sayers and P. D. James. Lynette Gaye Field Bachelor of Arts with First Class Honours in English. Graduate Diploma in English. This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia, School of Social and Cultural Studies, Discipline of English and Cultural Studies. 2011 ii iii TABLE OF CONTENTS STATEMENT OF CONTRIBUTION v ABSTRACT vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ix INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER ONE 27 This England CHAPTER TWO 70 At War CHAPTER THREE 110 Imperial Adventures CHAPTER FOUR 151 At Home AFTERWORD 194 WORKS CITED 199 iv v STATEMENT OF CANDIDATE CONTRIBUTION I declare that the thesis is my own composition with all sources acknowledged and my contribution clearly identified. The thesis has been completed during the course of enrolment in this degree at The University of Western Australia and has not previously been accepted for a degree at this or any other institution. This bibliographical style for this thesis is MLA (Parenthetical). vi vii ABSTRACT Dorothy L. Sayers and P. D. James are writers of classical detective fiction whose work is firmly anchored to a recognisably English culture, yet little attention has been given to this aspect of their work. I seek to redress this. Using Simon Gikandi’s concept of “the incomplete project of colonisation” ( Maps of Englishness 9) I argue that within the works of Sayers and James the British Empire informs and complicates notions of Englishness. Sayers’s Lord Peter Wimsey and James’s Adam Dalgliesh share, with Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, both detecting expertise and the character of the “imperial detective”. -

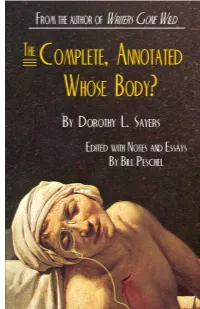

The Complete, Annotated Whose Body?

EXCERPT FROM The Complete, Annotated Whose Body? BY DOROTHY L. SAYERS With Notes, Essays and Chronologies by BILL PESCHEL AUTHOR OF ‘WRITERS GONE WILD’ Peschel Press ~ Hershey, Pa. Available in Trade Paperback, Kindle and other e-reader versions. EXCERPT FROM THE COMPLETE, ANNOTATED WHOSE BODY? Author’s Note This excerpt contains Chapter One, the essays and chronologies of Dorothy L. Sayers‘ life and Lord Peter Wimsey‘s cases. This is what you‘ll see if you buy the trade paperback book (minus this Author‘s Note, of course). The Wimsey Annotations project (at www.planet peschel.com) has been in the works for nearly 15 years and is not yet finished. With the rise in self-publishing, combined with the fact that Sayers‘ first two novels are in the public domain, the time was right for an annotated edition. Researching Sayers‘ life and that of her most famous creation provided fascinating insights into the history of England and its peoples in the 1920s. Sayers was also a well- educated woman, at a time when few women were, and her learning is reflected in Lord Peter‘s aphorisms, witty sayings and direct quotations of everything from classic literature, to Gilbert and Sullivan, to catchphrases of the day. I hope you‘ll find reading ―The Complete, Annotated Whose Body?‖ as enjoyable as I had researching it. Cheers, Bill Peschel THE COMPLETE, ANNOTATED WHOSE BODY? A novel by Dorothy L. Sayers in the public domain in the United States. Notes and Essays Copyright © 2011 Bill Peschel. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. -

Fatal Fascinations

Fatal Fascinations Fatal Fascinations: Cultural Manifestations of Crime and Violence Edited by Suzanne Bray and Gérald Préher Fatal Fascinations: Cultural Manifestations of Crime and Violence, Edited by Suzanne Bray and Gérald Préher This book first published 2013 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2013 by Suzanne Bray, Gérald Préher and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5134-5, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5134-3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................... vii Suzanne Bray and Gérald Préher Part I: Crime and Violence in Fiction First Steps Towards a Theology of English Detective Fiction .................... 1 Suzanne Bray Policing Madness, Diagnosing Badness: Personality Disorder and Criminal Behaviour in Sebastian Faulks’s Engleby ............................ 15 Charlotte Allen The Otherness Within, the Otherness Without: William Gilmore Simms’s “Confessions of a Murderer” ...................................................... 29 Gérald Préher Dancing to the Rhythm of the Triple Why-Dunnit: Toni Morrison’s Jazz as Crime Story