Paul Czinner's Fräule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROSALIND-Film-Links

THE PLAY “AS YOU LIKE IT” THE WOMAN ROSALIND SOME LINKS FOR YOUR VIEWING PLEASURE YOUTUBE…. FILM PRODUCTION TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX (1936) Directed by Paul Czinner Laurence Olivier, Elisabeth Bergner, Sophie Stewart With English Captions: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wFChichBoPI&t=16s Without English Captions: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RxBwHQSbUdY&list=RDCMUCWNH6WeWgwMaWbO_ 5VfhiTQ&start_radio=1&t=24 BBC – THE OPEN UNIVERSITY “AS YOU LIKE IT” DOCUMENTARY (2016) Award-winning British Actress Fiona Shaw Lectures, Scene Study with Exercises https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bTlH-EQSJE&t=2202s FULL AMATEUR PRODUCTIONS THE PUBLIC THEATER OF MINNESOTA SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL (2013) Filmed Outdoor Stage Production https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dDVnVpgzG5U&t=6848s SHAKESPEARE BY-THE-SEA (2015) Filmed Live Outdoor Stage Production https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZTSaCh02s8U&list=PLH0M7jdxVB3vfSQjS6gAMm6M3h Ox6cXP-&index=25 AUDIO RECORDING LIBRIVOX AUDIOBOOKS (2019) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hhcLW0FaCBk OREGON SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL (1950) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8yOhKvUtF3c&t=5539s KANOPY- FREE Through many Maine Public Libraries with Library card FILM PRODUCTION THE BBC SERIES – COMPLETE PLAYS OF SHAKESPEARE (1978) Directed by Basil Coleman Helen Mirren, Brian Stirner, Richard Pasco AMAZON PRIME VIDEO…… FILM PRODUCTIONS ROYAL SHAKESPEARE COMPANY (2019) Directed by Kimberly Sykes & Robert Lough Lucy Phelps , Antony Byrne , Sophie Khan Levy ROYAL SHAKESPEARE COMPANY (2010) Directed by Michael Boyd Jonjo O'Neill , Katy Stephens -

Shakespeare's Art and Artifice: Passing for Real in As You Like It

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2015-03-01 Shakespeare's Art and Artifice: assingP for Real in As You Like It Kristen Nicole Cardon Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Cardon, Kristen Nicole, "Shakespeare's Art and Artifice: Passing for Real in As You Like It" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 5657. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/5657 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Shakespeare’s Art and Artifice: Passing for Real in As You Like It Kristen Nicole Cardon A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Brandie R. Siegfried, Chair Matthew Farr Wickman Daniel K. Muhlestein Department of English Brigham Young University March 2015 Copyright © 2015 Kristen Nicole Cardon All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Shakespeare’s Art and Artifice: Passing for Real in As You Like It Kristen Nicole Cardon Department of English, BYU Master of Arts Gender performativity, detailed by Judith Butler and accepted by most contemporary queer theorists, rests on an agentive model of gender wherein “genders are appropriated, theatricalized, worn, and done” (“Imitation and Gender Insubordination” 716). This academic orthodoxy is challenged, however, by the increasing presence of transgender persons joining the theoretical discourse, many of whom experience an essential gender as a central facet of their identity. -

Original Writer Title Genre Running Time Year Director/Writer Actor

Original Running Title Genre Year Director/Writer Actor/Actress Keywords Writer Time Katharine Hepburn, Alcoholism, Drama, Tony Richardson; Edward Albee A Delicate Balance 133 min 1973 Paul Scofield, Loss, Play Edward Albee Lee Remick Family Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 53 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. I Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 54 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. II Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 53 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. III Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 53 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. IV Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 50 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. V Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 52 min 1995 Austen, -

Psychodrama Section Deal with Its Relationship to Psychoanalysis, Theoretically and Practically

Editorial Note This issue is again divided into sections. We gratefully acknowledge the work of Joe Hart in assembling and editing the Sociometry section. PSYCHODRAMA Psychodrama has for a long time filled the pages of the journal over SECTION whelmingly; it is good to see that the sociometric basis for Moreno's work is getting its proper share of attention. The papers cover a broad spectrum of applications. Among others, the attention paid the network theory reminds us that beyond the immediate social atom lies the network, from which influences impinge upon the smaller group and the individual which, though subtle, are very real. Two articles in the Psychodrama section deal with its relationship to psychoanalysis, theoretically and practically. Does this forebode a trend? ESCAPE ME NEVER We shall be interested to observe this in the future. ZERKA T. MORENO ZERKA T. MORENO As a very young man Moreno's. play with children in the gardens of Vienna proved to be a seedbed from which his therapeutic methods developed. He wrote about these story games in Das Koenigreich der Kinder (The Kingdom of the Children) in 1908. It was not without pride that he described how, given the opportunities he provided, one child after another revealed true dramatic talent. S01ne went on in later life to distinguished careers in the theater. Of these, perhaps the most talented and most widely acclaimed was the actress Elisabeth Bergner. An ornament to the stage in Max Reinhardt"s theater in Berlin, in London with Charles Cochran, in films with Alexander Korda and her husband Paul Czinner, and on tours around the world, the films she made are considered cine,na classics. -

Tim Bergfelder

Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION: GERMAN-SPEAKING EMIGRÉS AND BRITISH CINEMA, 1925–50: CULTURAL EXCHANGE, EXILE AND THE BOUNDARIES OF NATIONAL CINEMA Tim Bergfelder Britain can be considered, with the possible exception of the Netherlands, the European country benefiting most from the diaspora of continental film personnel that resulted from the Nazis’ rise to power.1 Kevin Gough- Yates, who pioneered the study of exiles in British cinema, argues that ‘when we consider the films of the 1930s, in which the Europeans played a lesser role, the list of important films is small.’2 Yet the legacy of these Europeans, including their contribution to aesthetic trends, production methods, to professional training and to technological development in the film industry of their host country has been largely forgotten. With the exception of very few individuals, including the screenwriter Emeric Pressburger3 and the producer/director Alexander Korda,4 the history of émigrés in the British film industry from the 1920s through to the end of the Second World War and beyond remains unwritten. This introductory chapter aims to map some of the reasons for this neglect, while also pointing towards the new interventions on the subject that are collected in this anthology. There are complex reasons why the various waves of migrations of German-speaking artists to Britain, from the mid-1920s through to the postwar period, have not received much attention. The first has to do with the dominance of Hollywood in film historical accounts, which has given prominence to the -

Mapping the British Biopic: Evolution, Conventions, Reception and Masculinities

Mapping the British Biopic: Evolution, Conventions, Reception and Masculinities Matthew Robinson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts, Creative Industries and Education, University of the West of England, Bristol June 2016 90,792 words Contents Abstract 2 Chapter One: Introduction 3 Chapter Two: Critical Review 24 Chapter Three: Producing the British Biopic 1900-2014 63 Chapter Four: The Reception of the British Biopic 121 Chapter Five: Conventions and Themes of the British 154 Biopic Chapter Six: This is His Story: ‘Wounded’ Men and 200 Homosocial Bonds Chapter Seven: The Contemporary British Biopic 1: 219 Wounded Men Chapter Eight: The Contemporary British Biopic 2: 263 Homosocial Recoveries Chapter Nine: Conclusion 310 Bibliography 323 General Filmography 355 Appendix One: Timeline of the British Biopic 1900-2014 360 Appendix Two: Distribution of Gender and Professional 390 Field in the British Biopic 1900-2014 Appendix Three: Column and Pie Charts of Gender and 391 Profession Distribution in British Biopics Appendix Four: Biopic Production as Proportion of Total 394 UK Film Production Previously Published Material 395 1 Abstract This thesis offers a revaluation of the British biopic, which has often been subsumed into the broader ‘historical film’ category, identifying a critical neglect despite its successful presence throughout the history of the British film industry. It argues that the biopic is a necessary category because producers, reviewers and cinemagoers have significant investments in biographical subjects, and because biopics construct a ‘public history’ for a broad audience. -

Fräulein Else – Stummfilm Mit Musikalischer Begleitung Freitag, 3., Und Samstag, 4

Fräulein Else – Stummfilm mit musikalischer Begleitung Freitag, 3., und Samstag, 4. 9. 2004 In Zusammenarbeit mit Cineteca Bologna und unter der musikalischen Leitung von Marco Dalpane, Bologna. Musik im Auftrag des ZDF. Wir danken der Spielfilmredak- tion von ZDF ARTE für die freundliche Unterstützung. Fräulein Else, Deutschland 1929, ca. 90 Minuten, restaurierte Fassung Regie: Paul Czinner, Drehbuch: Paul Czinner (nach Motiven der gleichnamigen Novelle von Arthur Schnitzler), Else: Elisabeth Bergner Else, die Tochter des Wiener Rechtsanwalts Dr. Thalhoff, wird bei einem Ferienaufenthalt in St. Moritz von einer bösen Nachricht überrascht. Ihr Vater hat sich verspekuliert, ihm droht strafrechtliche Verfolgung. Nur einer könnte helfen: der reiche Kunsthändler, Herr von Dorsday, der auch in St. Moritz weilt. An ihn wendet sich Else auf inständige Bitte ihrer Mutter. Von Dorsday ist bereit, Elses Vater zu helfen, allerdings unter einer Bedingung: Er will Else nackt sehen. Türöffnung: 19.30 Uhr Beginn 20.30 Fräulein Else Deutschland 1929, Länge: ca 90‘ Restaurierte Fassung Regie Paul Czinner Drehbuch Paul Czinner (nach Motiven der gleichnamigen Novelle von Arthur Schnitzler) Dramaturgische Mitarbeit Carl Meyer (ohne Credit) Kamera Karl Freund, Robert Baberske, Adolf Schlasy Bauten Erich Kettelhut Produktion Poetic-Film Originallänge 2.434 m (= 97‘ bei 22 f/sec) Else Elisabeth Bergner Dr. Thalhoff, Elses Vater Albert Bassermann Elses Mutter Else Heller Herr von Dorsday, Kunsthändler Albert Steinrück Tante Emma Adele Sandrock Paul, ihr Sohn Jack Trevor Cissy Mohr Grit Hegesa Restaurierte Fassung (2004) 2.272 m (= 90’ bei 22 f/sec) Restaurierung Cineteca di Bologna – in Kooperation mit Danske Filminstitut und ZDF/ARTE Umkopierung L’Immagine Ritrovata, Bologna Musik (2004 – i. -

Shakespeare Filmography

Shakespeare Filmography ENGL 205, 305, 306, and 507 — Professor William Hamlin Updated: 12 January 2015 All’s Well That Ends Well. Dir. John Dove. With Ellie Piercy, Sam Crane, and Janie Dee. Globe Theatre On Screen, 2011. Color. 138 minutes. All’s Well That Ends Well. National Theatre, London, 2009. See: www.youtube.com/watch?v=ae60Q0sr281 Antony and Cleopatra. Dir. Trevor Nunn. With Richard Johnson, Janet Suzman, Patrick Stewart, Rosemary McHale, Mavis Taylor Blake, Darien Angadi. 1975. Color. 161 minutes. Cleopatra. Dir. Joseph L. Mankiewicz. With Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor, Rex Harrison. Color. 1963. 246 minutes. As You Like It. Dir. Paul Czinner. With Laurence Olivier, Elisabeth Bergner. UK. 1936. Black and white. As You Like It. Dir. Kenneth Branagh. With Alfred Molina, Kevin Kline, Bryce Dallas-Howard, Romola Garai, Adrian Lester, Janet McTeer, David Oyelowo. 2007. Color. 127 minutes. Coriolanus. Dir. Ralph Fiennes. With Ralph Fiennes, Vanessa Redgrave, Gerard Butler, Brian Cox, Jessica Chastain. Color. 2011. 124 minutes. Hamlet. Dir. Laurence Olivier. With Laurence Olivier, Basil Sydney, Eileen Herlie, Jean Simmons, Peter Cushing. UK. 1948. Black and white. 155 minutes. Hamlet. Dir. Richard Burton. With Richard Burton, Hume Cronyn, Alred Drake, Eileen Herlie. 1964. Black and white. 191 minutes. Hamlet. Dir. Grigori Kosintsev. With Innokenti Smoktunovski. 1964. Hamlet at Elsinore. Dir. Philip Saville. With Christopher Plummer, Robert Shaw, June Tobin, Michael Caine, Jo Maxwell Muller, Roy Kinnear, Donald Sutherland. 1964. Black and white. 166 minutes. Hamlet. Dir. Rodney Bennett. With Derek Jacobi, Patrick Stewart, Claire Bloom. BBC and Time- Life Television Productions. 1980. Color. 215 minutes. Hamlet. Dir. -

Translating Surfaces: Shakespeare's As You Like It

http://northernrenaissance.org | ISSN: 1759-3085 Published under an Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported Creative Commons License. You are free to share, copy and transmit this work under the following conditions: • Attribution — You must attribute the work to the author, and you must at all times acknowledge the Journal of the Northern Renaissance as the original place of publication (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). • Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. • No Derivative Works — You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Issue 8 (2017) - Scrutinizing Surfaces Translating Surfaces: Shakespeare’s As You Like It, 1599-1989 Liz Oakley-Brown [1] Andrzej Krauze’s artwork for Tim Albery’s 1989 Old Vic production of Shakespeare’s As You Like It (c. 1599) crafts a striking perspective of the play.[1] His illustration of printed ink on paper fusing skinscape and landscape – the contours of a finely fashioned (feminine?) profile resemble a sparse green-spiked forest encircled by a smooth hirsute hinterland – nimbly captures the comedy’s famous dramatisation of unstable borders, margins and frames. Krauze’s textural design, however, simultaneously raises questions about As You Like It’s engagement with the surface: that ‘boundary condition that comes into being through the active relation of two or more distinct entities or conditions,…The sur-face, as a facing above or upon (sur-) a given thing’ which ‘refers first of all back to the thing it surfaces, rather than to a relation between two or more things’ (Hookway 2014:12). -

IT's TIME to DIE by Krzysztof Zanussi

IT’S TIME TO DIE by Krzysztof Zanussi translated by Anna Piwowarska // Stephen Davies 1 INTRODUCTION The grim title of this book originates from an anecdote and I ask you to treat it as a joke. I don’t intend to die soon or persuade anyone to relocate to the afterworld. But a certain era is dying before our very eyes and if someone is very attached to it, they should take my words to heart. This is what this book is to be about. But first, about that anecdote. It comes from a great actor, Jerzy Leszczynski. For me, a fifty-something-year-old, this surname is still very much alive. I saw Jerzy in a few roles in the ‘Polish Theatre’ just after the war; I also saw him in many pre-war films (after the war I think he only acted in ‘Street Boundary’). He was an actor from those pre-war years: handsome, endowed with a wonderful appearance and a beautiful voice. He played kings, military commanders, warlords and this is how the audiences loved him. After the war, he acted in radio plays – he had beautiful pre-war diction and of course he pronounced the letter ‘ł’ and he didn't swallow his vowels. Apart from this, he was known for his excellent manners, which befitted an actor who played kings and military commanders. When the time of the People’s Republic came, the nature of the main character that was played out on stage changed. The recruitment of actors also changed: plebeian types were sought after - 'bricklaying teams' and 'girls on tractors who conquered the spring'. -

The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays / Siegfried Kracauer ; Translated, Edited, and with an Introduction by Thomas Y

Siegfried Kracauer was one of the twentieth century's most brilliant cultural crit ics, a bold and prolific scholar, and an incisive theorist of film. In this volume his important early writings on modern society during the Weimar Republic make their long-awaited appearance in English. This book is a celebration of the masses—their tastes, amusements, and every day lives. Taking up the master themes of modernity, such as isolation and alienation, mass culture and urban experience, and the relation between the group and the individual, Kracauer explores a kaleidoscope of topics: shop ping arcades, the cinema, bestsellers and their readers, photography, dance, hotel lobbies, Kafka, the Bible, and boredom. For Kracauer, the most revela tory facets of modern metropolitan life lie on the surface, in the ephemeral and the marginal. The Mass Ornament today remains a refreshing tribute to popu lar culture, and its impressively interdisciplinary essays continue to shed light not only on Kracauer's later work but also on the ideas of the Frankfurt School, the genealogy of film theory and cultural studies, Weimar cultural politics, and, not least, the exigencies of intellectual exile. This volume presents the full scope of his gifts as one of the most wide-ranging and penetrating interpreters of modern life. "Known to the English-language public for the books he wrote after he reached America in 1941, most famously for From Caligari to Hitler, Siegfried Krac auer is best understood as a charter member of that extraordinary constella tion of Weimar-era intellectuals which has been dubbed retroactively (and mis- leadingly) the Frankfurt School. -

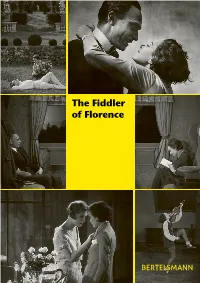

The Fiddler of Florence Contents

The Fiddler of Florence Contents Introduction 2 Greetings 4 The Movie Overview 6 Short bios 8 Contemporary Press Reviews 18 The Revival The Restoration 22 The Music 30 The Background Historical Background 36 The Publishers 42 Publishing Credits, Legal Notice, Footnotes and Picture Credits 45 3 Fortunately, Tucholsky’s last critics (apart from Bergner’s scenes, “Bergner! Bergner! cheered wish didn’t come true. The following the critics were especially taken with the gallery. And those of year, the celebrated theater actress ap- the original landscape shots from Tus- peared in front of the camera for the cany, which was still so far away at us who were there bowed first time in a movie by her future the time), was shortened enormously husband Paul Czinner, followed in by its U.S. distributor. Thanks to the our heads, and blessed her, 1925/26 by THE FIDDLER OF FLORENCE, elaborate restoration and reconstruc- and wished her all the best. the opening movie of this year’s UFA tion by the Friedrich Wilhelm Mur- Film Nights, which is able to be shown nau Foundation, however, the movie Praying that God would in full again for the first time. is now available again in a complete Elisabeth Bergner was an icon and digitized version, almost one preserve her, so young, of her time. The actress, born in 1897 hundred years after its creation. in Drohobycz in present-day Ukraine Digitization currently poses the so beautiful, so fair. and raised in Vienna, embodied an greatest challenge. Anything that isn’t And that film would stay ideal of beauty of the 1920s.