Report of the Special Commission of Inquiry Into Crystal Methamphetamine and Other Amphetamine-Type Stimulants 1001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Welcome to Broken Hill and the Far West Region of NSW

Welcome to Broken Hill and the far west region of NSW WELCOME Broken Hill New Residents Guide Welcome ! ! ! ! to the far west of NSW The city of Broken Hill is a relaxed and welcoming community as are the regional communities of Silverton, Wilcannia, White Cliffs, Menindee, Tibooburra & Ivanhoe. Broken Hill the hub of the far west of NSW is a thriving and dynamic regional city that is home to 18,000 people and we are pleased to welcome you. Your new city is a place, even though remote, where there are wide open spaces, perfectly blue and clear skies, amazing night skies, fantastic art community, great places to eat and socialise, fabulous sporting facilities, and the people are known as the friendliest people in the world. Broken Hill is Australia’s First Heritage City, and has high quality health, education, retail and professional services to meet all of your needs. The lifestyle is one of quality, with affordable housing, career opportunities and education and sporting facilities. We welcome you to the Silver City and regional communities of the far west region of NSW. Far West Proud is an initiative of Regional Development Australia Far West to promote the Far West of NSW as a desirable region to relocate business and families. WELCOME Broken Hill New Residents Guide Welcome to broken hill Hi, and welcome to Broken Hill, Australia’s first Heritage Listed City. You will soon discover that we are more than just a mining town. Scratch the surface and you’ll find a rich and vibrant arts scene, a myriad of sports and fitness options, and an abundance of cultural activities to enjoy. -

Worimi Sea Country (Garuwa) Artworks a CULTURAL INTERPRETATION ABOUT the ARTIST Melissa Lilley

Worimi Sea Country (Garuwa) Artworks A CULTURAL INTERPRETATION ABOUT THE ARTIST Melissa Lilley Melissa Lilley is a proud Yankunytjatjara woman from Central Australia, a Introduction descendant of this ancient land, has been traditionally taught to share her culture through interpretive art. Melissa produces artworks that are culturally connected through traditional Aboriginal stories, and uses techniques that are a continuation Worimi People of the temperate east coast have many special animals that live in of a living history that is thousands of generations old. Moving from the desert garuwa (sea country). region many years ago, she married into a traditional Worimi family from Port Stephens and learned the ways of coastal mobs of New South Wales. This move Djarrawarra (mulloway), for example, is a culturally significant fish known as the into a sea country community has subsequently enabled her to combine the best ‘greatest one’ (wakulgang). This makurr (fish) lives in all garuwa environmental areas of both worlds and develop an art form of unique characteristics. including buna (beaches), waraapiya (harbours), bandaa (lakes) and bila (river) systems. Worimi fishers regard djarrawarra as the prize catch, a species that requires Melissa has been producing cultural artworks for over 25 years, and has developed high levels of skills and passed on knowledge to be successful at catching it. an expertise in the field of cultural interpretation. This recognition has been achieved after many years of being taught by traditional artists, spending time with her Biiwa (mullet) is another garuwa species that is highly regarded by Worimi People. Elders and learning from other traditional Elders from various Aboriginal nations. -

The Builders Labourers' Federation

Making Change Happen Black and White Activists talk to Kevin Cook about Aboriginal, Union and Liberation Politics Kevin Cook and Heather Goodall Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Cook, Kevin, author. Title: Making change happen : black & white activists talk to Kevin Cook about Aboriginal, union & liberation politics / Kevin Cook and Heather Goodall. ISBN: 9781921666728 (paperback) 9781921666742 (ebook) Subjects: Social change--Australia. Political activists--Australia. Aboriginal Australians--Politics and government. Australia--Politics and government--20th century. Australia--Social conditions--20th century. Other Authors/Contributors: Goodall, Heather, author. Dewey Number: 303.484 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover images: Kevin Cook, 1981, by Penny Tweedie (attached) Courtesy of Wildlife agency. Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History RSSS and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National -

Ntscorp Limited Annual Report 2010/2011 Abn 71 098 971 209

NTSCORP LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2010/2011 ABN 71 098 971 209 Contents 1 Letter of Presentation 2 Chairperson’s Report 4 CEO’s Report 6 NTSCORP’s Purpose, Vision & Values 8 The Company & Our Company Members 10 Executive Profiles 12 Management & Operational Structure 14 Staff 16 Board Committees 18 Management Committees 23 Corporate Governance 26 People & Facilities Management 29 Our Community, Our Service 30 Overview of NTSCORP Operations 32 Overview of the Native Title Environment in NSW 37 NTSCORP Performing the Functions of a Native Title Representative Body 40 Overview of Native Title Matters in NSW & the ACT in 2010-2011 42 Report of Performance by Matter 47 NTSCORP Directors’ Report NTSCORP LIMITED Letter OF presentation THE HON. JennY MacKlin MP Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister, RE: 2010–11 ANNUAL REPORT In accordance with the Commonwealth Government 2010–2013 General Terms and Conditions Relating to Native Title Program Funding Agreements I have pleasure in presenting the annual report for NTSCORP Limited which incorporates the audited financial statements for the financial year ended 30 June 2011. Yours sincerely, MicHael Bell Chairperson NTSCORP NTSCORP ANNUAL REPORT 10/11 – 1 CHAIrperson'S Report NTSCORP LIMITED CHAIRPERSON’S REPORT The Company looks forward to the completion of these and other ON beHalF OF THE directors agreements in the near future. NTSCORP is justly proud of its involvement in these projects, and in our ongoing work to secure and members OF NTSCORP, I the acknowledgment of Native Title for our People in NSW. Would liKE to acKnoWledGE I am pleased to acknowledge the strong working relationship with the NSW Aboriginal Land Council (NSWALC). -

The City of Broken Hill National Heritage Listing the City of Broken Hill Was Included in the National Heritage List on 20 January 2015

The City of Broken Hill National Heritage Listing The City of Broken Hill was included in the National Heritage List on 20 January 2015. The City of Broken Hill is of outstanding heritage value to the nation for its significant role in the development of Australia as a modern and prosperous country. This listing recognises the City of Broken Hill’s mining operations, its contribution to technical developments in the field of mining, its pioneering role in the development of occupational health and safety standards, and its early practice of regenerating the environment in and around mining operations. Broken Hill is 935 km north-west of Sydney, 725 km north-west of Melbourne and 420 km north-east of Adelaide. The city’s isolated location means the town has developed its own distinctive characteristics expressed in the town’s architecture, design and landscaping. The By 1966 the total ore mined at Broken Hill reached people of Broken Hill have a strong connection to their 100 million tons, yielding 12.98 million tons of lead, heritage and surrounding dramatic desert landscape and are 9.26 million tons of zinc and 693.4 million ounces of recognised for their self reliance and resilience as a remote silver valued at £1 336 million. Mining revenues from inland community. Broken Hill were vital to the development of Australia, contributing hundreds of millions of dollars to government Building a nation administration, defence, education and research. The rich mineral deposits of Broken Hill enabled the Discovered by boundary rider and prospector, Charles Rasp creation and growth of some of the world’s largest mining in 1883, Broken Hill contains one of the world’s largest companies such as BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto and Pasminco. -

Finding Aid Available Here [797

O:\divisions\Cultural Collections @ UON\All Coll\NBN Television Archive\NBN PRODUCTIONS_TOPIC GROUPED\NEWS and ROVING EYE\2_VIDEOTAPE ... 1982 to 2019\BETACAM (1986 1999)Tapes\1B Betacam Tapes Film TITLE Other Information Date Track No. no. 1B_23 O.S. Sport Mentions Australian (Indigenous) player ‘Jamie Sandy’ 4/5/1986 4 (overseas) – Formerly from Redcliffe 1B_27 Art Gallery A few images of Indigenous art are prominent – 8/5/1986 7 though V/O glosses over. 1B_32 Peace Panel Panel includes Father Brian Gore (see 1B_26 – track 16/5/1986 2 5), Local Coordinator of Aboriginal Homecare Evelyn Barker – National Inquiry supported by the Aus council of Churches and Catholic Commission of Justice and Peace Human Rights issues. https://search.informit.org/fullText;dn=29384136395 4979;res=IELAPA This journal entry has an older photo on file. A quick google search indicates that Aunty Evelyn worked in Dubbo until her passing in 2014. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this footage contains images, voices or names of deceased persons in photographs, film, audio recordings or printed material. 1B_35 Boxing Includes images of an Indigenous Boxer: Roger Henry 28/5/1986 3 His record is attached: http://www.fightsrec.com/roger-henry.html 1B_40 Peace Bus Nuclear Disarmament. Bus itself includes a small 9/6/1986 9 painted Aboriginal flag along with native wildlife and forestry. Suggests a closer relationship between these groups 1B_42 Rail Exhibit Story on the rail line’s development and includes 13/6/1986 10 photos of workers. One of these is a photo of four men at ‘Jumbunna’ an Indigenous institute at UTS and another of rail line work. -

The History of the Worimi People by Mick Leon

The History of the Worimi People By Mick Leon The Tobwabba story is really the story of the original Worimi people from the Great Lakes region of coastal New South Wales, Australia. Before contact with settlers, their people extended from Port Stephens in the south to Forster/Tuncurry in the north and as far west as Gloucester. The Worimi is made up of several tribes; Buraigal, Gamipingal and the Garawerrigal. The people of the Wallis Lake area, called Wallamba, had one central campsite which is now known as Coomba Park. Their descendants, still living today, used this campsite 'til 1843. The Wallamba had possibly up to 500 members before white contact was made. The middens around the Wallis Lake area suggest that food from the lake and sea was abundant, as well as wallabies, kangaroos, echidnas, waterfowl and fruit bats. Fire was an important feature of life, both for campsites and the periodic 'burning ' of the land. The people now number less than 200 and from these families, in the main, come the Tobwabba artists. In their work, they express images of their environment, their spiritual beliefs and the life of their ancestors. The name Tobwabba means 'a place of clay' and refers to a hill on which the descendants of the Wallamba now have their homes. They make up a 'mission' called Cabarita with their own Land Council to administer their affairs. Aboriginal History of the Great Lakes District The following extract is provided courtesy of Great Lakes Council (Narelle Marr, 1997): In 1788 there were about 300,000 Aborigines in Australia. -

Black and White Children in Welfare in New South Wales and Tasmania, 1880-1940

‘Such a Longing’ Black and white children in welfare in New South Wales and Tasmania, 1880-1940 Naomi Parry PhD August 2007 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Parry First name: Naomi Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD School: History Faculty: Arts and Social Sciences Title: ‘Such a longing’: Black and white children in welfare in New South Wales and Tasmania, 1880-1940 Abstract 350 words maximum: When the Human Rights and Equal Opportunities Commission tabled Bringing them home, its report into the separation of indigenous children from their families, it was criticised for failing to consider Indigenous child welfare within the context of contemporary standards. Non-Indigenous people who had experienced out-of-home care also questioned why their stories were not recognised. This thesis addresses those concerns, examining the origins and history of the welfare systems of NSW and Tasmania between 1880 and 1940. Tasmania, which had no specific policies on race or Indigenous children, provides fruitful ground for comparison with NSW, which had separate welfare systems for children defined as Indigenous and non-Indigenous. This thesis draws on the records of these systems to examine the gaps between ideology and policy and practice. The development of welfare systems was uneven, but there are clear trends. In the years 1880 to 1940 non-Indigenous welfare systems placed their faith in boarding-out (fostering) as the most humane method of caring for neglected and destitute children, although institutions and juvenile apprenticeship were never supplanted by fostering. Concepts of child welfare shifted from charity to welfare; that is, from simple removal to social interventions that would assist children's reform. -

Agenda of Ordinary Meeting of the Council

May 23, 2018 Please address all communications to: ORDINARY MONTHLY MEETING The General Manager 240 Blende Street TO BE HELD PO Box 448 Broken Hill NSW 2880 WEDNESDAY, MAY 30, 2018 Phone 08 8080 3300 Fax 08 8080 3424 [email protected] Dear Sir/Madam, www.brokenhill.nsw.gov.au Your attendance is requested at the Ordinary Meeting of the Council of the ABN 84 873 116 132 City of Broken Hill to be held in the Council Chamber, Sulphide Street, Broken Hill on Wednesday, May 30, 2018 commencing at 6:30pm to consider the following business: 1) Apologies 2) Prayer 3) Acknowledgement of Country 4) Public Forum 5) Minutes for Confirmation 6) Disclosure of Interest 7) Mayoral Minute 8) Notice of Motion 9) Notices of Rescission 10) Reports from Delegates 11) Reports 12) Committee Reports 13) Questions Taken on Notice from Previous Council Meeting 14) Questions for Next Meeting Arising from Items on this Agenda 15) Confidential Matters JAMES RONCON GENERAL MANAGER LIVE STREAMING OF COUNCIL MEETINGS PLEASE NOTE: This Council meeting is being streamed live, recorded, and broadcast online via Facebook. To those present in the gallery today, by attending or participating in this public meeting you are consenting to your image, voice and comments being recorded and published. The Mayor and/or General Manager have the authority to pause or terminate the stream if comments or debate are considered defamatory or otherwise inappropriate for publishing. Attendees are advised that they may be subject to legal action if they engage in unlawful behaviour or commentary. A U S T R A L I A ' S F I R S T H E R I T A G E L I S T E D C I T Y ORDINARY MEETING OF THE COUNCIL 30 MAY 2018 MINUTES FOR CONFIRMATION Minutes of the Ordinary Meeting of the Council of the City of Broken Hill held Thursday, April 26, 2018. -

Yarnupings Issue4 Nov 2019

YARNUPINGS ABORIGINAL HERITAGE OFFICE NEWSLETTER ISSUE #4 NOVEMBER 2019 YARNUPINGS ABORIGINAL HERITAGE OFFICE NEWSLETTER ISSUE #4 NOVEMBER 2019 Welcome to the fourth and final issue of Yarnupings for 2019! We would like to thank everyone for a great year. Throughout the year we have seen the Aboriginal Heritage Office flourish in our new location in Freshwater. The Museum looks great and we have enjoyed showing our many visitors and groups our fantastic displays and sharing what we know about them. As always, we would be delighted to have you, your friends and family come and pop in. We also want to give a big shout out to all the volunteers who visited their sites in 2019. Your work is invaluable and we are grateful for your time and effort and contribution to preserving the spectac- ular Aboriginal cultural heritage of Northern Sydney and Strathfield region. We hope you enjoy our bumper Christmas edition, where hopefully there is something for everyone. The AHO Team— Dave, Karen, Phil, Susan, Claire and Samaka. In this issue... ● Walking in Willoughby ………… 2 ● Yarn Up ……….………………… 3 ● Year of Indigenous Language ... 3 ● 360 Photography………………... 4 ● School Archaeological Dig……... 4 ● Whispers from the Museum……. 5 ● Coastal Erosion Project…………. 7 ● Gringai………….………………… 9 ● Noongah Country….………..…... 11 ● Sense of Entitlement…………… 13 ● Crossword………………………. 15 ● Quiz……………………………… 16 ● Christmas Party Invite…………. 17 ● Bush Tucker Recipe…………… 17 ABORIGINAL HERITAGE OFFICE NEWSLETTER ISSUE 4 NOVEMBER 2019 Walking in Willoughby The Aboriginal Heritage Office has been enjoying the bushland of Willoughby LGA as part of a full council review of registered Aboriginal sites in the area. This summer grab your shoes, hat and cam- era and head out to one of the many glori- ous walks through Willoughby. -

A Thesis Submitted by Dale Wayne Kerwin for the Award of Doctor of Philosophy 2020

SOUTHWARD MOVEMENT OF WATER – THE WATER WAYS A thesis submitted by Dale Wayne Kerwin For the award of Doctor of Philosophy 2020 Abstract This thesis explores the acculturation of the Australian landscape by the First Nations people of Australia who named it, mapped it and used tangible and intangible material property in designing their laws and lore to manage the environment. This is taught through song, dance, stories, and paintings. Through the tangible and intangible knowledge there is acknowledgement of the First Nations people’s knowledge of the water flows and rivers from Carpentaria to Goolwa in South Australia as a cultural continuum and passed onto younger generations by Elders. This knowledge is remembered as storyways, songlines and trade routes along the waterways; these are mapped as a narrative through illustrations on scarred trees, the body, engravings on rocks, or earth geographical markers such as hills and physical features, and other natural features of flora and fauna in the First Nations cultural memory. The thesis also engages in a dialogical discourse about the paradigm of 'ecological arrogance' in Australian law for water and environmental management policies, whereby Aqua Nullius, Environmental Nullius and Economic Nullius is written into Australian laws. It further outlines how the anthropocentric value of nature as a resource and the accompanying humanistic technology provide what modern humans believe is the tool for managing ecosystems. In response, today there is a coming together of the First Nations people and the new Australians in a shared histories perspective, to highlight and ensure the protection of natural values to land and waterways which this thesis also explores. -

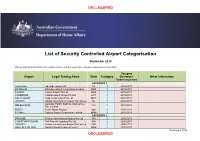

Airport Categorisation List

UNCLASSIFIED List of Security Controlled Airport Categorisation September 2018 *Please note that this table will continue to be updated upon new category approvals and gazettal Category Airport Legal Trading Name State Category Operations Other Information Commencement CATEGORY 1 ADELAIDE Adelaide Airport Ltd SA 1 22/12/2011 BRISBANE Brisbane Airport Corporation Limited QLD 1 22/12/2011 CAIRNS Cairns Airport Pty Ltd QLD 1 22/12/2011 CANBERRA Capital Airport Group Pty Ltd ACT 1 22/12/2011 GOLD COAST Gold Coast Airport Pty Ltd QLD 1 22/12/2011 DARWIN Darwin International Airport Pty Limited NT 1 22/12/2011 Australia Pacific Airports (Melbourne) MELBOURNE VIC 1 22/12/2011 Pty. Limited PERTH Perth Airport Pty Ltd WA 1 22/12/2011 SYDNEY Sydney Airport Corporation Limited NSW 1 22/12/2011 CATEGORY 2 BROOME Broome International Airport Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 CHRISTMAS ISLAND Toll Remote Logistics Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 HOBART Hobart International Airport Pty Limited TAS 2 29/02/2012 NORFOLK ISLAND Norfolk Island Regional Council NSW 2 22/12/2011 September 2018 UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED PORT HEDLAND PHIA Operating Company Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 SUNSHINE COAST Sunshine Coast Airport Pty Ltd QLD 2 29/06/2012 TOWNSVILLE AIRPORT Townsville Airport Pty Ltd QLD 2 19/12/2014 CATEGORY 3 ALBURY Albury City Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 ALICE SPRINGS Alice Springs Airport Pty Limited NT 3 11/01/2012 AVALON Avalon Airport Australia Pty Ltd VIC 3 22/12/2011 Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia NT 3 22/12/2011 AYERS ROCK Pty Ltd BALLINA Ballina Shire Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 BRISBANE WEST Brisbane West Wellcamp Airport Pty QLD 3 17/11/2014 WELLCAMP Ltd BUNDABERG Bundaberg Regional Council QLD 3 18/01/2012 CLONCURRY Cloncurry Shire Council QLD 3 29/02/2012 COCOS ISLAND Toll Remote Logistics Pty Ltd WA 3 22/12/2011 COFFS HARBOUR Coffs Harbour City Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 DEVONPORT Tasmanian Ports Corporation Pty.