Subafilms, Ltd. V. MGM-Pathe Communications Patricia Scahill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Designation Lpb 559/08

REPORT ON DESIGNATION LPB 559/08 Name and Address of Property: MGM Building 2331 Second Avenue Legal Description: Lot 7 of Supplemental Plat to Block 27 to Bell and Denny’s First Addition to the City of Seattle, according to the plat thereof recorded in Volume 2 of Plats, Page 83, in King County, Washington; Except the northeasterly 12 feet thereof condemned for widening 2nd Avenue. At the public meeting held on October 1, 2008, the City of Seattle's Landmarks Preservation Board voted to approve designation of the MGM Building at 2331 Second Avenue, as a Seattle Landmark based upon satisfaction of the following standard for designation of SMC 25.12.350: C. It is associated in a significant way with a significant aspect of the cultural, political, or economic heritage of the community, City, state or nation; and D. It embodies the distinctive visible characteristics of an architectural style, period, or of a method of construction. STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE This building is notable both for its high degree of integrity and for its Art Deco style combining dramatic black terra cotta and yellowish brick. It is also one of the very few intact elements remaining on Seattle’s Film Row, a significant part of the Northwest’s economic and recreational life for nearly forty years. Neighborhood Context: The Development of Belltown Belltown may have seen more extensive changes than any other Seattle neighborhood, as most of its first incarnation was washed away in the early 20th century. The area now known as Belltown lies on the donation claim of William and Sarah Bell, who arrived with the Denny party at Alki Beach on November 13, 1851. -

View Show Notes

https://archive.org/details/bigpicturemoneyp00epst/page/14 So there’s not a whole lot on the notes front for this episode because I didn’t have a ton of time to write anything out but I have been reading through Wikipedia pages for a couple days and wrote a little bit. This one is going to be about the history of Hollywood or, more specifically, the history of major motion picture production companies. Also just for the record, or more just to tell you, for the vinyl episode and my future episode about the music industry Ehtisham and I alluded to I kind of set up the background information and then I’m going to bring it forward into today, but with this episode and its future companion episode I intend to do the opposite. In the film industry there is what are known as ‘The Big 5’ companies, (for the record depending on who you ask and what time period you are working in this could be the Big 4-6 so it gets tricky) these are the ones that produce an absolutely massive amount of the media we consume. According to Wikipedia this means companies that make 80-85% of the box office revenue made in the country. This concept is not too recent however, as the Big 5 as we know them today are the second iteration of the group. The original Big 5 were: MGM, Paramount, Fox, Warner Bros., and RKO. The current Big 5 are: Universal, Paramount, Warner Bros., Disney, and Columbia. I plan on just kinda going through the old Big 5 and then the new Big 5 one by one, following their beginning and rise and/or demise. -

El Cine De Animación Estadounidense

El cine de animación estadounidense Jaume Duran Director de la colección: Lluís Pastor Diseño de la colección: Editorial UOC Diseño del libro y de la cubierta: Natàlia Serrano Primera edición en lengua castellana: marzo 2016 Primera edición en formato digital: marzo 2016 © Jaume Duran, del texto © Editorial UOC (Oberta UOC Publishing, SL) de esta edición, 2016 Rambla del Poblenou, 156, 08018 Barcelona http://www.editorialuoc.com Realización editorial: Oberta UOC Publishing, SL ISBN: 978-84-9116-131-8 Ninguna parte de esta publicación, incluido el diseño general y la cubierta, puede ser copiada, reproducida, almacenada o transmitida de ninguna forma, ni por ningún medio, sea éste eléctrico, químico, mecánico, óptico, grabación, fotocopia, o cualquier otro, sin la previa autorización escrita de los titulares del copyright. Autor Jaume Duran Profesor de Análisis y Crítica de Films y de Narrativa Audiovi- sual en la Universitat de Barcelona y profesor de Historia del cine de Animación en la Escuela Superior de Cine y Audiovi- suales de Cataluña. QUÉ QUIERO SABER Lectora, lector, este libro le interesará si usted quiere saber: • Cómo fueron los orígenes del cine de animación en los Estados Unidos. • Cuáles fueron los principales pioneros. • Cómo se desarrollaron los dibujos animados. • Cuáles han sido los principales estudios, autores y obras de este tipo de cine. • Qué otras propuestas de animación se han llevado a cabo en los Estados Unidos. • Qué relación ha habido entre el cine de animación y la tira cómica o los cuentos populares. Índice -

The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Film Studies (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-2021 The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Michael Chian Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/film_studies_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chian, Michael. "The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood." Master's thesis, Chapman University, 2021. https://doi.org/10.36837/chapman.000269 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film Studies (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood A Thesis by Michael Chian Chapman University Orange, CA Dodge College of Film and Media Arts Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Film Studies May, 2021 Committee in charge: Emily Carman, Ph.D., Chair Nam Lee, Ph.D. Federico Paccihoni, Ph.D. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Copyright © 2021 by Michael Chian III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my advisor and thesis chair, Dr. Emily Carman, for both overseeing and advising me throughout the development of my thesis. Her guidance helped me to both formulate better arguments and hone my skills as a writer and academic. I would next like to thank my first reader, Dr. Nam Lee, who helped teach me the proper steps in conducting research and recognize areas of my thesis to improve or emphasize. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

The Decline and Fall of the European Film Industry: Sunk Costs, Market Size and Market Structure, 1890-1927

Working Paper No. 70/03 The Decline and Fall of the European Film Industry: Sunk Costs, Market Size and Market Structure, 1890-1927 Gerben Bakker © Gerben Bakker Department of Economic History London School of Economics February 2003 Department of Economic History London School of Economics Houghton Street London, WC2A 2AE Tel: +44 (0)20 7955 6482 Fax: +44 (0)20 7955 7730 Working Paper No. 70/03 The Decline and Fall of the European Film Industry: Sunk Costs, Market Size and Market Structure, 1890-1927 Gerben Bakker © Gerben Bakker Department of Economic History London School of Economics February 2003 Department of Economic History London School of Economics Houghton Street London, WC2A 2AE Tel: +44 (0)20 7955 6482 Fax: +44 (0)20 7955 7730 Table of Contents Acknowledgements_______________________________________________2 Abstract________________________________________________________3 1. Introduction___________________________________________________4 2. The puzzle____________________________________________________7 3. Theory______________________________________________________16 4. The mechanics of the escalation phase _____________________________21 4.1 The increase in sunk costs______________________________________21 4.2 The process of discovering the escalation parameter _________________29 4.3 Firm strategies_______________________________________________35 5. Market structure ______________________________________________47 6. The failure to catch up _________________________________________54 7. Conclusion __________________________________________________63 -

Aron Siegel, C.A.S. Production Sound Mixer

ARON SIEGEL, C.A.S. PRODUCTION SOUND MIXER FEATURES Senior Year w/ Rebel Wilson – Paramount Worldwide Productions Director – Alex Hardcastle; Producers – Todd Garner, Tim Bourne, Rebel Wilson Thor: Ragnarok – MARVEL STUDIOS (Principal unit - Atlanta) Director – Taika Waititi; Producers – David Grant, Kevin Feige The Founder w/ Michael Keaton, Filmnation, WEINSTEIN COMPANY Director – John Lee Hancock; Producers - Don Handfield, Jeremy Renner, Michael Sledd, Aaron Ryder All Eyez On Me – The Tupac Shakur Story, Morgan Creek / LIONSGATE Director – Benny Boom; Producers - James Robinson, David Robinson, Wayne Morris, LT Hutton, Paddy Cullen Last Looks w/ Charlie Hunnam, Mel Gibson – Romulus Entertainment Director – Tim Kirkby; Producers – Brad Feinstein, Brian Pitt, Andrew Lazar Cosmic Sin w/ Bruce Willis, Luke Wilson - Saban Pictures/Paramount Pictures Director - Edward Drake; Producers – Joe DiMaio, Dan Katzman Neighbors 2: Sorority Rising w/ Seth Rogen & Zac Efron, UNIVERSAL PICTURES Director – Nicholas Stoller; Producers - Ted Gidlow, Robert Mazaraki, Seth Rogen St Agatha – St Agatha Productions / Octane Entertainment Director – Darren Lynn Bousman; Producers - Srdjan Stakic, Sara Sometti Stephen King's 'Cell' w/ John Cusack, Samuel L. Jackson, Stacey Keach – Saban Films Director - Kip Williams; Producers - Richard Saperstein, Shara Kay, Paddy Cullen Creed w/ Michael B Jordan, Sylvester Stallone – MGM/NEW LINE/WARNER BROTHERS (Atlanta Unit) Director – Ryan Coogler; Producers Nicolas Stern, Irwin Winkler Kill the Messenger w/Jeremy Renner, -

Paramount Pictures

Before we start with the individual studios, let’s cover one additional situation. It didn’t really belong in the last chapter because it is more of a research problem. But it is one that should be addressed. Many of the major studios submitted their primary production code numbers to the Library of Congress. These records are a tremendous help with one caveat. Almost all of the production codes submitted DID NOT INCLUDE THE LETTER PREFIX THAT WAS ASSIGNED BY SOME OF THE INDIVIDUAL STUDIOS. So, while the production code number would be the same, only some have letter prefixes. In several instances, there are different letter prefixes. The bottom line is that numbers recorded at the Library of Congress may require additional research. Columbia Pictures Columbia’s production codes are by far the most confusing and most difficult to use for identification. This may be an indication that Columbia was not quite certain how to effectively number and utilize production codes. - - Columbia started production codes for their 1926- 1927 season. The first film to have codes was False Alarm, which was issued a “C-1” production code. They produced 24 films that season, marking them “C -1” through “C-24.” The Library of Congress records show only the numbers 1-24, but the stills reflect the letter “C,” a dash (-) and the number. The next season (1927-1928), they produced 30 films, with the first one being The Blood Ship. Instead of issuing new production codes, they simply started over with their numbering, marking them “C-1” through “C-30.” The next season (1928-1929), they produced 31 films, starting with Court Martial. -

SAMUEL GOLDWYN (NOT) BORN 8/27/1882 Most of the Pioneers Who Started the Film Business About 120 Years Ago Are Unfamiliar Names Today

Monday, August 23, 2021 | No. 182 Film Flashback… SAMUEL GOLDWYN (NOT) BORN 8/27/1882 Most of the pioneers who started the film business about 120 years ago are unfamiliar names today. Samuel Goldwyn is an exception – but for the wrong reason. People recognize Goldwyn as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's middle name, but don't realize he was never part of MGM. Actually, Goldwyn wasn't even the legendary producer's birth name and August 27, 1882 wasn't really his birthday – although he always said it was. No one knows the real date, but it's agreed he was born in Warsaw and anglicized his name to Samuel Goldfish. In 1913, as a successful New York glove salesman, he became interested in making movies. With difficulty, Sam convinced his then brother-in-law, Jesse Lasky, that there was big money in films. They began by producing the first feature film ever made in Hollywood, The Squaw Man. Sam stayed in New York to sell the distribution rights. From the start, Sam was a difficult partner no matter whom he partnered with. He enjoyed fighting just for the sake of fighting – even with people who agreed with him. This led to big problems when Lasky merged with Adolph Zukor's Famous Players. Zukor was president of both Click to Play FP-L and its distribution arm. Goldfish was chairman of FP-L, which later adopted its distributor's name – Paramount Pictures. By August 1916, Zukor and Goldwyn's relationship had deteriorated so badly that Zukor gave Lasky an ultimatum – either Goldfish goes or Zukor goes. -

Disaster Recovery for Media & Entertainment with Spectra

Disaster Recovery for Media & Entertainment with Spectra BlackPearl Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................... 3 Incidents, Accidents & Disasters ................................................................... 3 The Value of Content ....................................................................................... 4 What is Disaster Recovery? ........................................................................... 5 Protecting Assets with a Disaster Recovery Strategy ................................ 6 BlackPearl Methods of Protection ................................................................. 7 What About the Database? ............................................................................. 8 The Cost of Offsite Media Storage ................................................................. 9 Conclusion ........................................................................................................ 9 Copyright ©2017 Spectra Logic Corporation. All rights reserved worldwide. Spectra and Spectra Logic are registered trademarks of Spectra Logic. All other trademarks and registered trademarks are the property of their respective owners. All features and specifications listed in this white paper are subject to change at any time without notice. Disaster Recovery for Media & Entertainment with Spectra BlackPearl 2 Introduction It’s not about if. It’s about when. Without a solid disaster recovery plan in place, media and entertainment -

Early Classical Hollywood Cinema 1900'S-In The

Early Classical Hollywood Cinema 1900’s-In the early 1900s, motion pictures ("flickers") were no longer innovative experiments/scapist entertainment medium for the working-class masses/ Kinetoscope parlors, lecture halls, and storefronts turned into nickelodeon. Admission 5 cents (sometimes a dime) - open from early morning to midnight. 1905-First Nickelodean -Pittsburgh by Harry Davis in June of 1905/few theatre shows in US- shows GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY Urban, foreign-born, working-class, immigrant audiences loved the cheap form of entertainment and were the predominent cinema-goers Some of the biggest names in the film business got their start as proprietors, investors, exhibitors, or distributors in nickelodeons.:Adolph Zukor ,Marcus Loew, Jesse Lasky, Sam Goldwyn (Goldfish), the Warner brothers, Carl Laemmle, William Fox, Louis B. Mayer 1906-According to most sources, the first continuous, full-length narrative feature film (defined as a commercially-made film at least an hour in length) was Charles Tait's biopic of a notorious outback bushranger, The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906, Australia)- Australia was the only country set up to regularly produce feature-length films prior to 1911.- 1907-Griffith begins working for Edision- Edwin S. Porter's and Thomas Edison's Rescued From the Eagle's Nest (1907)/ Griffith- Contributing to the modern language of cinema, he used the camera and film in new, more functional, mobile ways with composed shots, traveling shots and camera movement, split-screens, flashbacks, cross-cutting (showing two simultaneous actions that build toward a tense climax), frequent closeups to observe details, fades, irises, intercutting, parallel editing, dissolves, changing camera angles, soft-focus, lens filters, and experimental/artificial lighting and shading/tinting. -

1076 (1909), Codified at 17 U.S.C

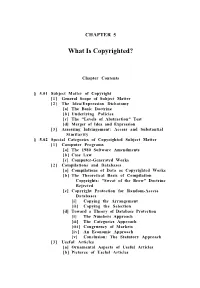

CHAPTER 5 What Is Copyrighted? Chapter Contents § 5.01 Subject Matter of Copyright [1] General Scope of Subject Matter [2] The Idea/Expression Dichotomy [a] The Basic Doctrine [b] Underlying Policies [c] The "Levels of Abstraction" Test [d] Merger of Idea and Expression [3] Assessing Infringement: Access and Substantial Similarity § 5.02 Special Categories of Copyrighted Subject Matter [1] Computer Programs [a] The 1980 Software Amendments [b] Case Law [c] Computer-Generated Works [2] Compilations and Databases [a] Compilations of Data as Copyrighted Works [b] The Theoretical Basis of Compilation Copyrights: "Sweat of the Brow" Doctrine Rejected [c] Copyright Protection for Random-Access Databases [i] Copying the Arrangement [ii] Copying the Selection [d] Toward a Theory of Database Protection [i] The Numbers Approach [ii] The Categories Approach [iii] Congruency of Markets [iv] An Economic Approach [v] Conclusion: The Statutory Approach [3] Useful Articles [a] Ornamental Aspects of Useful Articles [b] Pictures of Useful Articles [c] Plans, Drawings, and Models for Useful Articles [i] Eligibility of Plans, Drawings, and Models for Copyright Protection [ii] Limits on Protection [4] Architecture [a] The Separate Legal Regime for Building De- signs [b] Subject Matter Covered: Building Designs [c] Limitations on Copyright Protection for Building Designs [d] Prospectivity of Protection § 5.03 Prerequisites for Copyright Protection: Fixation, Originality, and Creativity [1] Fixation [a] New Technology [b] Communicative Function [c] What "Fixation" Means [i] Author's Authorization [ii] Tangible Medium and Permanence [d] Fixation and Interactive Systems [e] Fixation and Copyright Preemption [2] Originality [3] Creativity [4] What Copyright Does Not Require [a] The Difference Between Copyright and Patent Standards [b] Content and Copyright Protection § 5.01 Subject Matter of Copyright Patents and trade secrets may protect concepts in the broad sense.