Ali to Flood to Marshall: the Most Triumphant of Words, 9 Marq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century Saesha Senger University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.011 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Senger, Saesha, "Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 150. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/150 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

We Are Santa's Elves (6Th Grade) Jolly Old St. Nicholas (Kindergarten) O

We Are Santa’s Elves (6th Grade) O Come All Ye Faithful (5th Grade) Ho Ho Ho! Ho Ho Ho! O come, all ye faithful We are Santa's elves. Joyful and triumphant We are Santa's elves, O come ye, o come ye to Bethlehem Filling Santa's shelves with a toy Come and behold Him For each girl and boy. Born the King of Angels! Oh, we are Santa's elves. O come, let us adore Him O come, let us adore Him We work hard all day, O come, let us adore Him But our work is play. Christ the Lord Dolls we try out, See if they cry out. Sing, choirs of angels We are Santa's elves. Sing in exultation Sing all ye citizens of heaven above We've a special job each year. Glory to God in the highest We don't like to brag. O come, let us adore Him Christmas Eve we always O come, let us adore Him Fill Santa's bag. O come, let us adore Him Santa knows who's good. Christ the Lord Do the things you should. And we bet you, Silent Night (3rd Grade) He won't forget you. Silent night, holy night We are Santa's elves. All is calm, all is bright 'Round yon virgin Mother and Child Ho Ho Ho! Ho Ho Ho! Holy infant so tender and mild We are Santa's elves. Sleep in heavenly peace Ho Ho! Sleep in heavenly peace Silent night, holy night! Jolly Old St. Nicholas (Kindergarten) Shepherds quake at the sight! Jolly old St.Nicholas Glories stream from heaven afar; Lean your ear this way Heavenly hosts sing Al-le-lu-ia! Don't you tell a single soul Christ the Savior is born! What I'm going to say Christ the Savior is born! Christmas Eve is coming soon The First Noel (4th Grade) Now, my dear old man The First Noel, the Angel did say Whisper what you'll bring to me Was to certain poor shepherds Tell me if you can In fields as they lay. -

Symphonic Santa Sunday!

AUDIENCE PARTICIPATION! UPCOMING MUSICAL EVENTS ❆ BY THE THE FERRIS STATE UNIVERSITY MUSIC CENTER LYRICS TO: FSU MUSIC CENTER ENSEMBLES in conjunction with 2009-10 The Marine Toy for Tots Foundation and Rotary International of Big Rapids “Christmas Sing-A-Long” FEBRUARY 14 (SU) FESTIVAL WINTER CONCERT presents 4:00 p.m. FSU G. Mennen Williams Auditorium FSU Symphony Band Hark, the Herald Angels Sing in conjunction with the FSU West Central Concert Band ❆ Hark, the Herald Angels Sing, “Glory to the new-born King!” 2010 Festival of the Arts FSU West Central Chamber Orchestra Peace on Earth and mercy mild, God and sinners reconciled. MARCH 3 (WE) JAZZ BAND CONCERT Joyful, all ye nations rise, Join the triumph of the skies 8:00 p.m. FSU Rankin Center Dome Room FSU Jazz Band With angelic host proclaim, “Christ is born in Bethlehem.” A Hark, the Herald Angels Sing, “Glory to the new-born King!” APRIL 6 (TU) CHOIR CONCERT 8:00 p.m. FSU Rankin Center Dome Room FSU Concert Choir O Come, All Ye Faithful APRIL 21 (WE) FSU 125TH ANNIVERSARY CONCERT Symphonic O come, all ye faithful, Joyful and triumphant; 4:00 p.m. FSU G. Mennen Williams Auditorium FSU Symphony Band O come ye, O come ye to Bethlehem. FSU West Central Concert Band Come and behold Him, Born the King of angels: FSU West Central Chamber Orchestra O come let us adore Him, O come let us adore Him, APRIL 24 (SA) CHORAL & JAZZ CONCERT WITH ALUMNI Santa O come let us adore Him, Christ the Lord. -

Community Carol Sing Deck the Halls I Saw Three Ships

COMMUNITY CAROL SING DECK THE HALLS I SAW THREE SHIPS TABLE Deck the halls with boughs of holly, I saw three ships come sailing in, Fa la la la la, la la la la. On Christmas day, On Christmas day. OF CONTENTS Tis the season to be jolly... I saw three ships come sailing in, Don we now our gay apparel... On Christmas day in the morning. DECK THE HALLS page 3 Troll the ancient Yuletide carol... And what was in those ships all three… The Virgin Mary and Christ were there… O COME, ALL YE FAITHFUL page 3 See the blazing Yule before us... Pray, whither sailed those ships all I SAW THREE SHIPS page 3 Strike the harp and join the chorus... three.. Follow me in merry measure... O they sailed into Bethlehem… HERE WE COME A-WASSAILING page 3 While I tell of Yuletide treasure... page 4 IT CAME UPON A MIDNIGHT CLEAR Fast away the old year passes, HERE WE COME A-WASSAILING Hail the new, ye lads and lasses... HARK! THE HERALD ANGELS SING page 4 Here we come a-wassailing Among Sing we joyous, all together... the leaves so green; Here we come GOD REST YE MERRY GENTLEMEN page 5 Heedless of the wind and weather... a-wandering, So fair to be seen. RUDOLPH THE RED-NOSED REINDEER page 5 Chorus: Love and joy come to you, O COME ALL YE FAITHFUL JINGLE BELLS page 6 And to you our wassail, too. O come all ye faithful, And God bless you and JINGLE BELL ROCK page 6 joyful and triumphant. -

The Life Triumphant: Mastering the Heart and Mind by James Allen

The Life Triumphant: Mastering the heart and mind By James Allen Contents 1. Foreword 2. Faith and Courage 3. Manliness, Womanliness and Sincerity 4. Energy and Power 5. Self-Control and Happiness 6. Simplicity and Freedom 7. Eight Thinking and Repose 8. Calmness and Resource 9. Insight and Nobility 10. Man the Master 11. Knowledge and Victory Foreword EVERY BEING LIVES in his own mental world. His joys and sorrows are the creations of his own mind, and are dependent upon the mind for their existence. In the midst of the world, darkened with many sins and sorrows, in which the majority live, there abides another world, lighted up with shining virtues and unpolluted joy, in which the perfect ones live. This world can be found and entered, and the way to it is by self-control and moral excellence. It is the world of the perfect life, and it rightly belongs to man, who is not complete until crowned with perfection. The perfect life is not the faraway, impossible thing that men who are in darkness imagine it to be; it is supremely possible, and very near and real. Man remains a craving, weeping, sinning, repenting creature just so long as he wills to do so by clinging to those weak conditions. But when he wills to shake off his dark dreams and to rise, he arises and achieves. James Allen Hail to Thee, Man divine! the conqueror Of sin and shame and sorrow; no more weak, Wormlike, and groveling art thou; no, nor Wilt thou again bow down to things that weak Scourgings and death upon thee; thou dost rise Triumphant in thy strength; good, pure and wise. -

Christmas Carol Lyrics

1 COMMUNITY CHORUS PROJECT, KIDZU CHILDREN’S MUSEUM & UNIVERSITY PLACE PRESENT A HOLIDAY SING ALONG! Conducted by Caroline Miceli & Accompanied by Scott Schlesinger JINGLE BELLS A pair of hopalong boots and a pistol that shoots Is the wish of Barney and Ben; Refrain: Jingle bells, jingle bells, jingle all the way Dolls that will talk and will go for a walk Oh, what fun it is to ride in a one horse open sleigh Is the hope of Janice and Jen; Jingle bells, jingle bells, jingle all the way And Mom and Dad can hardly wait for school to start again. Oh, what fun it is to ride in a one horse open sleigh It's beginning to look a lot like Christmas ev'rywhere you go; Dashing through the snow in a one horse open sleigh There's a tree in the Grand Hotel, one in the park as well, Over fields we go, laughing all the way The sturdy kind that doesn't mind the snow. Bells on bob tail ring, making spirits bright. It's beginning to look a lot like Christmas; What fun it is to ride & sing a sleigh song tonight! (Refrain) Soon the bells will start, And the thing that will make them ring is the carol that you A day or two ago I thought I'd take a ride sing right within your heart And soon Miss Fanny Bright was seated by my side; The horse was lean and lank. Misfortune seemed his lot, Santa Claus is Coming to Town We ran into a drifted bank and there we got upsot. -

“Whoever Welcomes This Child in My Name Welcomes Me…” ~ Luke 9:48 WITNESS Kindergarten in God’S Image

Year of WITNESS Curriculum Connections Elementary Religion Program Note to teachers: Every theme is introduced with a scripture quote for the teacher as catechist. These quotes are meant to inspire teachers and to help them understand the underlying purpose of the lessons, songs, and activities they will be doing with the children. Scripture is taught throughout the program through: story, song, gesture, drama, art, and symbols. “Whoever welcomes this child in my name welcomes me…” ~ Luke 9:48 WITNESS Kindergarten In God’s Image The metaphor “TRACE OF GOD” is used throughout In God’s Image, linking the resource to the activities, growth and very being of the young child. ‐“TRACE OF GOD” describes the qualities of 4/5 year olds who are creating a space for themselves in God’s world. ‐In each Theme, the children naturally and playfully bear Witness to all that God has created. WITNESS Grade 1—We Belong Unit 1: Welcome! You belong 1. Welcome p.39 A Different Kind of Magic Hello! Hello! Track #2 2. We belong p.45 We Belong to a Circle of Circle of Friends Track #3 Friends p.46 We Belong to a Family 3. We celebrate p.49-56 We Prepare to Celebrate Hello! Hello! Track #2 Celebrating together Circle of Friends Track #3 Let’s Remember our Celebration Unit 2: Jesus welcomes us 4. Jesus welcomes children p.60-61 We Listen to a story about Circle of Friends Track #3 Welcoming Good News Track #9 p.62-63 Adults welcome Us Let the Children Track #5 Come to me 5. -

Triumphant Trump Misconduct Accused of Intimidating Women Into Having Sex by ADRIENNE SARVIS [email protected]

IN SPORTS: Four local high school athletes sign with Division I colleges B1 Final Election Day results Please turn to page A6 THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 10, 2016 | Serving South Carolina since October 15, 1894 75 cents Ex-Sumter police officer arrested for Triumphant Trump misconduct Accused of intimidating women into having sex BY ADRIENNE SARVIS [email protected] South Carolina Law En- forcement Division arrested and charged a former Sumter Police Department officer with misconduct in office on Mon- day following an investigation into accusations of sexual co- ercion and intimi- dation. William McKin- ley Littlejohn, 35, faces three counts of miscon- duct in office and could serve 10 LITTLEJOHN years for each count if he is con- victed, according to a news re- lease from SLED. Sumter Police Department requested that SLED open an THE ASSOCIATED PRESS investigation after local offi- President-elect Donald Trump pumps his fist during an election night rally in New York. cers received information about the alleged acts. Tonyia McGirt, public infor- Republican candidate pulls off surprising upset over Clinton mation officer with the police department, said Littlejohn WASHINGTON (AP) — Donald threatens to undo major achievements publicly until later Wednesday. Trump, was suspended in December Trump claimed his place Wednesday as of President Barack Obama. Trump who spent much of the campaign urg- 2015 when SLED began its in- America’s 45th president, an astonish- has pledged to act quickly to repeal ing his supporters on as they chanted vestigation. ing victory for the celebrity business- Obama’s landmark health care law, re- “lock her up,” said the nation owed According to three warrants man and political novice who capital- voke America’s nuclear agreement Clinton “a major debt of gratitude” for issued by SLED on May 12, ized on voters’ economic anxieties, with Iran and rewrite important trade her years of public service. -

Student Says He Drowned His Son Mechanical Engineering Events That Led to the Arrest and Arraignment of the CSUF Student

All Across the Country United Against Hate DailyTitaN Cross Country attends its On-campus gay group appeals to www.dailytitan.comOnline first meet SPORTS, p. 8 ASI after assault NEWS, p. 2 Since 1960 Wednesday Volume 83, Issue 7 September 13, 2006 DailyThe Student Voice of California StateTitan University, Fullerton Student Says He Drowned His Son Mechanical engineering events that led to the arrest and arraignment of the CSUF student. student is being held in “He came into the front desk [of Arrest Stuns University police custody the Police Department] on 9:30 Sunday night and told the desk officer that he had killed his son,” Professors, Students BY ADAM LEVY & JOEY T. ENGLISH Petropulos said. “He just came in smiling with joy, Kreiner said. Daily Titan Staff Gideon Walter Omondi a matter-of-fact tone and told the “He was beaming with happiness [email protected] officer what he had done – we don’t ‘worshipped’ his son, that he got his family together.” usually get that.” Kreiner said. “They were going to Gideon Walter Omondi, a 35- Petropulos described the academic adviser says make a good life here.” BY KARL THUNMAN/Daily Titan Staff Photographer year-old Cal State Fullerton student, procedures then taken by the police Omondi was a very hard- LOOKING TO THE FUTURE - President Milton Gordon spoke with appeared Tuesday afternoon in the d e p a r t m e n t working and organized student students and staff alike at the Convocation about the many benefits and f o l l o w i n g BY LAURA lujAN & HARMONY TREVINO advantages of attending Cal State Fullerton. -

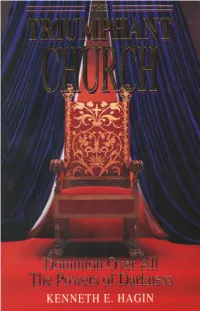

The Triumphant Church Are Constantly Ravaged by the Wiles of Satan and Are in a State of Continual Failure and Defeat

Kenneth E. Hagin Unless otherwise indicated, all Scripture quotations in this volume are from the King James Version of the Bible. Cover photograph of throne chair used by permission: Philbrook Museum of Art Tulsa, Oklahoma Fourth Printing 1994 ISBN 0-89276-520-8 In the U.S. Write: In Canada write: Kenneth Hagin Ministries Kenneth Hagin Ministries P.O. Box 50126 P.O. Box 335 Tulsa, OK 74150-0126 Etobicoke (Toronto), Ontario Canada, M9A 4X3 Copyright © 1993 RHEMA Bible Church AKA Kenneth Hagin Ministries, Inc. All Rights Reserved Printed The Faith Shield is a trademark of RHEMA Bible Church, AKA Kenneth Hagin Ministries, Inc., registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and therefore may not be duplicated. Contents 1 Origins: Satan and His Kingdom.................................5 2 Rightly Dividing Man: Spirit, Soul, and Body...........35 3 The Devil or the Flesh?...............................................69 4 Distinguishing the Difference Between Oppression, Obsession, and Possession...........................................107 5 Can a Christian Have a Demon?..............................143 6 How to Deal With Evil Spirits..................................173 7 The Wisdom of God...................................................211 8 Spiritual Warfare: Are You Wrestling or Resting?..253 9 Pulling Down Strongholds........................................297 10 Praying Scripturally to Thwart The Kingdom of Darkness.......................................................................329 11 Is the Deliverance Ministry Scriptural?.................369 12 Scriptural Ways to Minister Deliverance...............399 Chapter 1 1 Origins: Satan and His Kingdom Believers are seated with Christ in heavenly places, far above all powers and principalities of darkness. No demon can deter the believer who is seated with Christ far above all the works of the enemy! Our seating and reigning with Christ in heavenly places is a position of authority, honor, and triumph—not failure, depression, and defeat. -

O Come, All Ye Faithful, Joyful and Triumphant, O Come Ye, O Come Ye to Bethlehem; Come and Behold Him, Born the King of Angels

O come, all ye faithful, Joyful and triumphant, O come ye, O come ye to Bethlehem; Come and behold him, Born the King of angels. O come, let us adore him, O come, let us adore him, O Come, let us adore him, Christ the Lord. God of God, light of light, Lo, he abhors not the Virgin's womb; True God, begotten, not created. Lo! star-led chieftains, Magi, Christ adoring, Offer him incense, gold and myrrh; We to the Christ child Bring our heart’s oblations. Child, for us sinners Poor and in the manger, Fain we embrace thee, With awe and love: Who would not love thee, Loving us so dearly? We shall see the eternal splendor Of the eternal father, veiled in flesh, The infant God wrapped in cloths. Sing, choirs of angels, Sing in exultation, Sing, all ye citizens of heaven above; Glory to God All glory in the highest. Yea, Lord, we greet thee, Born this happy morning; Jesus, to thee be all glory given; Word of the Father, Now in flesh appearing. Focus Point: Christmas is about worship and we worship because of who Christ reveals God to be. 1. Lord He is the preexistent God. Before time, before anything, God existed. Exodus 3:14 I AM has sent me to you. John 8:58 Before Abraham was born, I AM! He is the creator. John 1:3,10 All things were made through him, and without him was not anything made that was made. 10 He was in the world, and the world was made through him, yet the world did not know him. -

XV. the Apostles' Creed in Biblical Perspective “I Believe...” “The Holy

XV. The Apostles’ Creed in Biblical Perspective “I Believe...” “The Holy catholic Church” Ephesians 2:19–22 Dr. Harry L. Reeder III September 27, 2020 • Sunday Sermon This is the Word of God. Ephesians 2:19–22 says [19] So then you are no longer strangers and aliens, but you are fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God, [20] built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Christ Jesus Himself being the cornerstone, [21] in whom the whole structure, being joined together, grows into a holy temple in the Lord. [22] In Him you also are being built together into a dwelling place for God by the Spirit. The grass withers, the flower fades, the Word of God abides forever and by His grace and mercy may His Word be preached for you. The Apostles’ Creed contain essentials distilled by those who had been discipled by the Apostles. The creed is the Apostolic writing of Christianity in the New Testament and how Christ is our Redeemer and the fulfillment of all the Old Covenant promises. It is laid out in a Trinitarian way, in the three paragraphs it contains. The Apostles’ Creed is as follows; I believe in God the Father Almighty, (first affirmation/1st Person of the Trinity) maker of heaven and earth; I believe in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord, (second affirmation/2nd Person of the Trinity) who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, and was buried; he descended into hades.