Lillooet Timber Supply Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duffey Lake Provincial Park

Duffey Lake Provincial Park M ANAGEMENT LAN P Prepared by: Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks BC Parks, Garibaldi/Sunshine Coast District Brackendale, B.C. in conjunction with: Ministry of Environment, Terra Firma Environmental Consultants Lands and Parks BC Parks Division Duffey Lake Provincial Park M ANAGEMENT LAN P PARK VISION Duffey Lake Park will continue to be an important part of the parks system on both a regional and provincial level. While the park is relatively small, its key habitat components, unique setting in the transition zone between the coast mountains and the dry interior, and recreational opportunities will make this area a favourite for both destination visitors and the travelling public. Should resource and rural development increase in nearby areas, Duffey Lake Park’s varied habitats for bear, deer, goats, raptors and other wildlife, particularly on the north-west side, will become even more important in providing wildlife the necessary food, cover and shelter to sustain populations in the region. The park will continue to have high water quality, sustained fish populations and together with the wetland habitats, continue to be a high quality aquatic ecosystem. Duffey Lake Park will continue to be important for First Nation traditional use and cultural values. BC Parks, together with the First Nation’s communities, will ensure that significant cultural sites within the park are protected from development impacts and that recreation activities in the park are respectful of the environment and First Nation traditional use. Visitors to the park will be attracted to the low-impact recreational opportunities including day-use and multi-day activities. -

Scanning Canada Scanning John David Corby, VA3KOT Report [email protected]

Scanning Canada Scanning John David Corby, VA3KOT Report [email protected] Into the Icefields Scanning Canada reader writes with of the Cayoosh Mountain. I had put my rental car Pemberton area. If you head out of town into a request: -a brand new, full-size Toyota - into low gear to the surrounding country looking for the source "I live in Calgary and I was so avoid over -heating the brakes as we hugged the of these signals, beware, this is bear country! pleased to see your column in Monitoring Times. curves down the long, steep, winding drop into I used to listen to the city police here quite a bit. the Lillooet River valley. The road had many pull- Logging Operations but a few years ago they switched to a digital outs for runaway trucks, but I had managed to 152.960 157.620 158.310158.550 158.580 165.000 system and I was out of luck. Finding frequencies keep the vehicle under control during the very. 167.940168.060 - Various commercial logging and trucking from Industry Canada is like asking them to pull very long descent. companies out all of their own teeth without any freezing. By the time we hit the valley the car's 'Fire, ambulance, police and armed forces frequen- transmission smelt badly overheated, but the First Nations Bands cies are not given out to the public.' is what I was fairly flat road into Pemberton allowed the car's 154.310 Mt.Currie firehall - Lillooet Tribal Council told on numerous occasions by our fine govern- fluids time to cool. -

Connection Call 604-230-8167 [email protected] Frankingham.Com

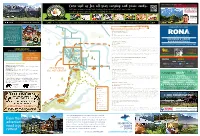

YOUR PEMBERTON Real Estate connection Call 604-230-8167 [email protected] FrankIngham.com FRANK INGHAM GREAT GOLF, FANTASTIC FOOD, EPIC VIEWS. EVERYONE WELCOME! R E A L E S T A T E Pemberton Resident For Over 20 Years 604-894-6197 | pembertongolf.com | 1730 Airport RD Relax and unwind in an exquisite PEMBERTON VALLEY yellow cedar log home. Six PEMBERTON & AREA HIKING TRAILS unique guest bedrooms with private bathrooms, full breakfast ONE MILE LAKE LOOP 1 and outdoor hot tub. Ideal for 1.45km loop/Approx. 30 minutes groups, families and corporate Easy retreats. The Log House B&B 1.3km / 1 minute by vehicle from Pemberton Inn is close to all amenities and PEMBERTON LOCAL. INDEPENDENT. AUTHENTIC. enjoys stunning mountain views. MEADOWS RD. Closest to the Village, the One Mile Lake Loop Trail is an easy loop around the lake that is wheelchair accessible. COLLINS RD. Washroom facilities available at One Mile Lake. HARDWARE & LUMBER 1357 Elmwood Drive N CALL: 604-894-6000 LUMPY’S EPIC TRAIL 2 BUILDING MATERIALS EMAIL: [email protected] 9km loop/ Approx. 4 hours WEB: loghouseinn.com Moderate 7426 Prospect street, Pemberton BC | 604 894 6240 URDAL RD. 1.3km / 1 minute by vehicle from Pemberton The trail is actually a dedicated mountain bike trail but in recent years hikers and mountain runners have used it to gain PROSPECT ST. access to the top of Signal Hill Mountain. The trail is easily accessed from One Mile Lake. Follow the Sea to Sky Trail to EMERGENCIES: 1–1392 Portage Road IN THE CASE OF AN EMERGENCY ALWAYS CALL 911 URCAL-FRASER TRAIL Nairn Falls and turn left on to Nairn One Mile/Lumpy’s Epic trail. -

Cayoosh Goat Survey Report 2008

Cayoosh Range Mountain goat survey in the Cayoosh area, management unit 3-16, Thompson region, British Columbia, July 2008 Prepared for: Doug Jury British Columbia Ministry of Environment Thompson Region 1259 Dalhousie Drive Kamloops, BC V2C 5Z5 Prepared by: Kim G. Poole Aurora Wildlife Research 2305 Annable Road, Nelson BC V1L 6K4 Tele. (250) 825-4063; e-mail: [email protected] September 2008 Cayoosh mountain goat survey, July 2008 ii ABSTRACT Mountain goats (Oreamnos americanus) are managed as a big game species in British Columbia, and as such aerial surveys are conducted periodically to document population trend and productivity, and to establish hunting quotas. As a result of suspected declines in the population and a 10-year gap since the last survey, a survey was conducted to determine the numbers and distribution of goats in subzones 3- 16B, C, D, E and F in the Pacific and Lillooet ranges of the Coast Mountains southwest of Lillooet, southeastern British Columbia, in July 2008. Standard survey techniques were followed using a Bell 206B helicopter. We used 18.4 hrs of helicopter time, including 15.7 hrs on survey, and surveyed a 675-km2 census zone of potential goat habitat under good survey conditions. Overall survey effort averaged 1.4 min/km2. We observed 210 goats (150 adults, 60 kids) in 56 groups. Kids comprised 29% of total goats (40 kids:100 adults [non-kids]). Groups were distributed from 5,400 to 8,100 feet (1,650–2,470 m) elevation. I applied a sightability correction factor of 60% to derive an estimate of 350 goats for the census zone within the 5 subzones (density of 0.52 goats/km2). -

Hit the Road Go Small from the Earth

2020-2021 FREE GO SMALL Intimate options for Spud Valley vows HIT THE ROAD Explore the mountains on motorcycle FROM THE EARTH Lil’wat artist’s driftwood throne AN OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF b o r n & r a i s e d t a p r o o m & f a r m b r e w e r y Farmers first - Brewers second; JOIN US on the farm this season. Crafting beer that is born and raised Featuring: Pumpkin Patch, in Pemberton. Locally-grown and Sunflower Maze and a locally consumed. taste of the Farm Life. 8324 Pemberton Meadows Rd, Pemberton, BC www.thebeerfarmers.com/visit | [email protected] COVER IMAGE: The sunflower fields of Pemberton have become one of the most photographed and Instragram-worthy spots in Pemberton over the past few years. A trip to our beautiful valley isn’t complete without a visit. ELCOME PHOTO BY GETTY IMAGES TO PEMBERTON ON BEHALF OF THE BOARD, I would like to thank you, the “tourist,” our most valuable player, for visiting Pemberton. Allow me also to thank our members, our board volunteers, partners, the Village CONTENTS of Pemberton, and the Squamish Lillooet Regional District. 2019 in Pemberton was a remarkably successful year. First Nations Artist 4 Despite some challenges with ongoing construction, Meet Lil’wat Nation talent Francis Billy and we experienced incredible amounts of snow for our catch a glimpse of his driftwood sculpture sledders, an early arrival of spring and of course the beautiful weather throughout the summer months. The winter season moving into 2020 was a little Happy Trails 6 slower due to our snow fall, but January saw a huge Hiking, camping and more dumping of snow. -

Helios Tourism Planning Group - I - 4.1.2 Assessment of Newly Established and Proposed Protected Areas

Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................................ i Preface -........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Part 1 – Introduction & Area Profile .......................................................................................................... 5 1.0 Background & Study Rationale .......................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Study Purpose...................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Methods .............................................................................................................................................. 6 1.2.1 Study Limitations......................................................................................................................... 8 1.3 General Area Profile .......................................................................................................................... 8 1.3.1 Management Jurisdictions......................................................................................................... 11 1.3.2 Area-based Access .................................................................................................................... 12 1.4 Nature-Based Tourism Profile......................................................................................................... -

Cayoosh Mountains

Vol.31 No.1 Winter 2012 Published by the Wilderness Committee FREE REPORT BENDOR AND CAYOOSH MOUNTAINS TRIBAL PARK PROTECTION NEEDED NOW! BEAUTIFUL LANDS OF THE ST'ÁT'IMC Joe Foy National Campaign Portage, Shalalth, Samahquam, Skatin which means they have pockets of both proposed tribal parks encompassing Director, and Douglas are strategically located on types of habitat. Unfortunately both the Bendor and Cayoosh mountains. Wilderness Committee trail and canoe routes that are thousands ranges are under threat from proposed This is an important step forward of years old near some of the world's industrial developments including that needs to be taken, and one most productive wild salmon rivers.1 logging and a proposed ski resort. So that is long overdue. Read on to Within St'át'imc territory are some of far the rugged nature of the Bendor and learn how you can help gain tribal here do I go when I want my favourite protected areas, including Cayoosh mountains and the courageous park protection for the Bendor and Wto see some of the wildest, portions of Garibaldi Provincial Park, nature of the St'át'imc people have Cayoosh mountains! most beautiful landscapes in the Stein Valley Nlaka'pamux Heritage been able to fend off the worst of the world? Where do I go when I want to Park and South Chilcotin Mountains industrial projects, which is why these Learn about the experience a place and a culture where Provincial Park. areas are still so wild and beautiful. But St'át'imc people people have lived for centuries upon However, two wilderness mountain for how long? centuries? I go to St'át'imc of course! ranges located in the heart of St'át'imc The St'át'imc have produced a land- and their land Several hundred kilometres to territory that are critical to the region's use plan for the northern portion of at statimc.net the north of Vancouver, BC lies the ecological and cultural well-being are their territory. -

DISTRICT of LILLOOET AGENDA a Regular Meeting of the Council Of

DISTRICT OF LILLOOET AGENDA A Regular Meeting of the Council of the District of Lillooet to be held in the Lillooet Recreation Centre, Room 201 at 930 Main Street, on Monday, October 3, 2016 at 7 PM Page 1. Call to Order 2. Adoption of Agenda (additions and/or deletions) 3. Public Input 4. Presentation(s) (a) Jason Quigley, Executive Vice President, Amarc Resources Ltd. Re: Mineral Exploration Project (IKE) 5. Delegation(s) 4-6 (a) Toby Mueller, Chief Librarian, Lillooet Area Library Association Re: SLRD Budget Goals & Objectives 2017 6. Adoption of Minutes 7-12 (a) September 12, 2016 Regular Meeting Minutes of Council for Adoption. STAFF RECOMMENDATION: THAT the following meeting minutes be adopted as presented: 1. Regular Meeting Minutes of Council, September 12, 2016 7. Business Arising from the Minutes 8. Correspondence 13-20 (a) Francis Iredale, Wildlife Biologist, FLNRO Re: Lillooet Alpine ATV Restrictions Information 21-23 (b) Bronwyn Barter, Provincial President, Ambulance Paramedics and Emergency Dispatchers of BC Re: What's going on with Ambulance services, and how is it impacting your community? 24 (c) Barry & Linda Sheridan Re: Cayoosh Creek Campground STAFF RECOMMENDATION: Page 1 of 54 District of Lillooet October 3, 2016 Agenda Listing Page 8. Correspondence THAT correspondence from Barry & Linda Sheridan regarding 'Cayoosh Creek Campground', dated September 10, 2016, be received. 25-28 (d) Cathy Peters, Speaker & Advocate addressing Human Trafficking/Sexual Exploitation in BC Re: Human Trafficking/Sexual Exploitation 29 (e) Steven Rice, Chair, Gold Country Communities Society Re: Invitation to Second Annual Tourism Symposium 30 (f) Amy Thacker, Chief Executive Officer, Cariboo Chilcotin Coast Tourism Association Re: Invitation to Annual General Meeting and Tourism Summit 31 (g) Terri Hadwin, Chief Operating Officer, Gold Country Communities Society Re: Thank You STAFF RECOMMENDATION: THAT correspondence from Terri Hadwin, Gold Country Communities Society, regarding "Thank You", dated September 18, 2016, be received. -

Mission Ridge Trail Rails & Trails Lake’.Youwillnoticethat Seton Lake

Code: GC3QN60 Rails & Trails Written and Researched by Wayne Robinson Mission Ridge Trail Site Identification Nearest Community: Lillooet, B.C. Geocache Location: N 50°45.787' W 122°10.185' Altitude: 2177m/7142ft Ownership: Crown Land Photo: Wayne Robinson Accuracy: 4 meters Overall Difficulty: 5 Overall Terrain: 5 Mission Ridge is named for an Oblate Mission that was founded in 1880 in the community of Shalath. Mission Access Information and Mountain was the first ‘official’ name given in 1918 and Restrictions: 4x4 only. From Mile 0 Cairn drive north the ridge was later described in a geological survey as on Main Street and turn left onto Hwy 40. overlooking Shalath and above Seton Lake. This vague At the junction at the east end of Carpenter description is thought to include three prominent peaks in Reservoir (48 km from Cairn) turn left on to Mission Mountain Road, cross the dam the centre of the entire ridge. The name was then changed and go through tunnel. At Mission Pass from ‘Mountain’ to ‘Ridge’ and now describes the summit turn on to road marked ‘No approximately 13 km long ridge that begins with Mission through Road/Dead End’. Go 5 km to Pass to the north and ends with Mount McLean to the junction of roads. Take road on the right. Approximately 3 km to trail head. Very south. The trail to the geocache on Mission Ridge is challenging hike – long and steep. Wear relatively short; it begins just below tree line and ends in appropriate footwear and hiking gear. the alpine. At the summit there are two geodesic domes. -

Thevarsity Outdoor

The Varsity Outdoor Ckb Journal VOLUME XVII 1974 ISSN 0524-5613 The UuvetAitj of IkitUh Columbia Vancouver, Canada PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE One October afternoon 5 years ago found a good friend and I driving home from U.B.C. after classes. He showed rae a sheet of words entitled "V.O.C. Pall Trip Schedule." "Just what is this V.O.C. anyway, and what do they do?" After men tioning something about an outdoor club, he read out a list of various hiking and mountaineering trips, trail workhikes, cabin workhites and mountaineering lectures that had been planned for the fall term. It really sounded goodl Over the next few days, I began noticing Varsity Outdoor Club posters telling of general meetings every Wednesday noonhour in Henry Angus 104 and decided to go to one. I hadn't really anticipated what I saw...in between announce ments and other comments made by a rather well spoken fellow who was apparently the chairman of the meeting, many different people with pres tigious-sounding titles were running in turn up to the stage, gleefully babbling some announce ment at a speed certainly exceeding that of sound, and then disappearing into the maze of faces before I could realize what had hit me. A Hallowe'en party coming up shortly was an nounced. .then a big roar from the audience as someone was awarded the 'Hot Dog of the Month' Award for some particularly notable stunt 'below and beyond the call of duty and/or above and beyond normal stupidity'. This was followed by an announcement of trips the coming weekend and finally by an excellent slide show put on by one of the members. -

![Nd ISOTOPIC SIGNATURES AN]) STRATIGRAPIIIC CORRELATIONS: EXAMPLES from WESTERN PACIFIC MARGINAL BASINS and MIDDLE JURASSIC ROCKS of the SOUTHERN CANADIAN CORDILLERA](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2243/nd-isotopic-signatures-an-stratigrapiiic-correlations-examples-from-western-pacific-marginal-basins-and-middle-jurassic-rocks-of-the-southern-canadian-cordillera-6372243.webp)

Nd ISOTOPIC SIGNATURES AN]) STRATIGRAPIIIC CORRELATIONS: EXAMPLES from WESTERN PACIFIC MARGINAL BASINS and MIDDLE JURASSIC ROCKS of the SOUTHERN CANADIAN CORDILLERA

Nd ISOTOPIC SIGNATURES AN]) STRATIGRAPIIIC CORRELATIONS: EXAMPLES FROM WESTERN PACIFIC MARGINAL BASINS AND MIDDLE JURASSIC ROCKS OF THE SOUTHERN CANADIAN CORDILLERA by J. Brian Mahoney B.S., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1983 M.S., Idaho State University, 1987 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGICAL SCIENCES We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August, 1994 © J. Brian Mahoney, 1994 ______________________________ In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Bntish Columbia, I agree that the Ubrary shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. (Signature Department of éZ)Lc2tcr <_tG’CL The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada ci Date ‘‘ U ‘ld?,EYL DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT The purpose of this investigation is twofold: 1) to evaluate the applicability of Nd and Sr isotopic analyses of fine grained clastic sediments to basin analysis and stratigraphic correlation; and 2) to document the lithostratigraphic, biostratigraphic, geochemical and isotopic characteristics of Lower to Middle Jurassic strata in tectonostratigraphic terranes of the southern Canadian Cordillera in order to evaluate potential terrane linkages. Isotopic analyses of Neogene strata from three western Pacific marginal basins (Shikoku Basin, Sea of Japan, Sulu Sea) permit evaluation of isotopic analyses to basin discrimination and stratigraphic correlation. -

Description of Non-Commercial Winter Recreation Zones

Descriptions of Non-Commercial Winter Recreation Zones Sea-to-Sky Land and Resource Management Plan The information contained in this document is from the report “Recommendations for Management of Winter Backcountry Recreation in the Lillooet River Drainage and the Sea-to Sky LRMP Area – Appendix A” (Gordon Erlandson, 2008), with minor revisions to ensure direction is consistent and accurate with LRMP zoning. The management direction referenced is not policy, but rather provides advice and guidance for the management of the non-commercial winter recreation zones established in the Sea-to-Sky Land and Resource Management Plan (S2S LRMP) amendment, Section 4.4.3, Map 15A. Commercial recreation management direction for the Squamish Nation Land Use Agreement area is established in Appendix 5 of the S2S LRMP. Should there be any discrepancies in references to commercial recreation between this document and Appendix 5, then please refer to the latter. The non-commercial winter recreation zones in the S2S LRMP area are: Non-motorized use (RA1) Self propelled activities that do not rely on a motorized vehicle for access or recreation use within a designated zone. Acceptable Uses / Activities: Existing motorized and / or non-motorized commercial recreation uses and activities are acceptable if present. Backcountry skiing, ski touring / mountaineering, cross-country / Nordic skiing, dog- sledding, snowshoeing Non-motorized transport only. New non-motorized uses may be considered. Non-motorized use with air access (RA1-A) Self propelled activities that do not rely on a motorized vehicle for recreation use within a designated zone. Acceptable Uses / Activities: Same uses as RA1, but aerial transport is allowed for drop off / pick-up of day use or multi-day recreation users.