Powell and Pressburger's Island Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, a MATTER of LIFE and DEATH/ STAIRWAY to HEAVEN (1946, 104 Min)

December 8 (XXXI:15) Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH/ STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN (1946, 104 min) (The version of this handout on the website has color images and hot urls.) Written, Produced and Directed by Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger Music by Allan Gray Cinematography by Jack Cardiff Film Edited by Reginald Mills Camera Operator...Geoffrey Unsworth David Niven…Peter Carter Kim Hunter…June Robert Coote…Bob Kathleen Byron…An Angel Richard Attenborough…An English Pilot Bonar Colleano…An American Pilot Joan Maude…Chief Recorder Marius Goring…Conductor 71 Roger Livesey…Doctor Reeves Robert Atkins…The Vicar Bob Roberts…Dr. Gaertler Hour of Glory (1949), The Red Shoes (1948), Black Narcissus Edwin Max…Dr. Mc.Ewen (1947), A Matter of Life and Death (1946), 'I Know Where I'm Betty Potter…Mrs. Tucker Going!' (1945), A Canterbury Tale (1944), The Life and Death of Abraham Sofaer…The Judge Colonel Blimp (1943), One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942), 49th Raymond Massey…Abraham Farlan Parallel (1941), The Thief of Bagdad (1940), Blackout (1940), The Robert Arden…GI Playing Bottom Lion Has Wings (1939), The Edge of the World (1937), Someday Robert Beatty…US Crewman (1935), Something Always Happens (1934), C.O.D. (1932), Hotel Tommy Duggan…Patrick Aloyusius Mahoney Splendide (1932) and My Friend the King (1932). Erik…Spaniel John Longden…Narrator of introduction Emeric Pressburger (b. December 5, 1902 in Miskolc, Austria- Hungary [now Hungary] —d. February 5, 1988, age 85, in Michael Powell (b. September 30, 1905 in Kent, England—d. Saxstead, Suffolk, England) won the 1943 Oscar for Best Writing, February 19, 1990, age 84, in Gloucestershire, England) was Original Story for 49th Parallel (1941) and was nominated the nominated with Emeric Pressburger for an Oscar in 1943 for Best same year for the Best Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Writing, Original Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Missing Missing (1942) which he shared with Michael Powell and 49th (1942). -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

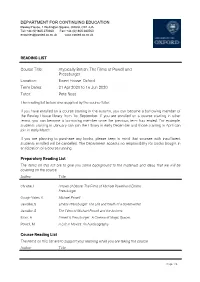

Reading List for Atypically British: the Films of Powell and Pressburger

DEPARTMENT FOR CONTINUING EDUCATION Rewley House, 1 Wellington Square, Oxford, OX1 2JA Tel: +44 (0)1865 270360 Fax: +44 (0)1865 280760 [email protected] www.conted.ox.ac.uk READING LIST Course Title: Atypically British: The Films of Powell and Pressburger Location: Ewert House, Oxford Term Dates: 21 Apr 2020 to 16 Jun 2020 Tutor: Pete Boss The reading list below was supplied by the course tutor. If you have enrolled on a course starting in the autumn, you can become a borrowing member of the Rewley House library from 1st September. If you are enrolled on a course starting in other terms, you can become a borrowing member once the previous term has ended. For example, students starting in January can join the Library in early December and those starting in April can join in early March. If you are planning to purchase any books, please keep in mind that courses with insufficient students enrolled will be cancelled. The Department accepts no responsibility for books bought in anticipation of a course running. Preparatory Reading List The items on this list are to give you some background to the materials and ideas that we will be covering on the course. Author Title Christie, I Arrows of Desire: The Films of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger Gough-Yates, K Michael Powell Jawolke, S Emeric Pressburger: The Life and Death of a Screenwriter Jawolke, S The Films of Michael Powell and the Archers Moor, A Powell & Pressburger : A Cinema of Magic Spaces Powell, M A Life in Movies: An Autobiography Course Reading List The items on this list are to support your learning while you are taking the course. -

Rights Catalogue 2021

RIGHTS CATALOGUE 2021 129 26 129 ‘Shiny dark licorice mind candy: nothing quite like them’ MARGARET ATWOOD (on Mayhem & Death) ‘She’s a writer completely unafraid’ ALI SMITH In a darkening season in a northern city, Daniel, Órla and Tom’s lives intersect through a peculiar flatshare and a stolen nineteenth-century diary written by a dashing gentleman who may not be entirely dead. An interwar-themed Hallowe’en party leads to a series of entanglements: a longed-for sexual encounter, 198 a betrayal, and a reality-destroying moment of possession. HELEN McCLORY As the consequences unfurl, Bitterhall’s narrative reveals the ways in which our subjectivity tampers Trimmed: (198H × 284W) Untrimmed: (208H × 294W) mm (198H × 284W) Untrimmed: Trimmed: with the notion of an objective reality, and delves into how we represent – and understand – our muddled, haunted selves. ISBN 978-1-84697-549-3 9 781846 975493 HELEN McCLORY £9.99 Prize-winning author of The Goldblum Variations www.polygonbooks.co.uk Cover design: gray318 Bitterhall 3D.indd All Pages 17/02/2021 14:43 jennybrownassociates.com Welcome We have been a literary agency based in Edinburgh since 2002. With the help of scouts and sub-agents, we sell rights to publishers all over the world. We are particularly known for representing writing from Scot- land, including literary fiction, crime writing, and narrative non-fiction, and books for children and young adults. Our bestselling and award-winning authors include crime writers such as Alex Gray (Little,Brown, series sales over 1 million copies) and Alison Belsham (The Tattoo Thief sold in 14 languages), non-fiction writers like Shaun Bythell (Diary of A Bookseller sold in to 25 languages), Saltire Book of the Year winner Kathleen Jamie, and children’s writers and illustrators such as Chris Edge, Jonathan Meres and Alison Murray. -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

Blind Spot: Hitler's Secretary

Blind Spot: Hitler’s Secretary Dir: Andre Heller and Othmar Schmiderer, Austria, 2003 A review by Jessica Lang, John Hopkins University, USA Blind Spot: Hitler's Secretary, a documentary film directed by Andre Heller and Othmar Schmiderer, is the first published account of Traudl Humps Junge's memories as Hitler's secretary from 1942 until his suicide in 1945. The ninety minute film, which came out in 2002, was edited from more than ten hours of footage. The result is a disturbing compilation of memories and reflections on those memories that, while interesting enough, are presented in a way that is at best uneven. Part of this unevenness is a product of the film's distribution of time: while it begins with Junge's recalling how she interviewed for her secretarial position in order to quit another less enjoyable job, most of it is spent reflecting on Hitler as his regime and military conquests collapsed around him. But the film also is not balanced in terms of its reflectivity, abandoning halfway through some of its most interesting and most important narrative strategies. In terms of its construction, the film involves Junge speaking directly to the camera. She speaks with little prompting (that the audience can hear, at least) and appears to have retained a footprint of war memories that has remained almost perfectly intact through the sixty years she has kept them largely to herself. Interrupted by sudden editing breaks, the viewer is rushed through the first two and a half years of Junge's employment in the first half of the film. -

Proud to Sponsor Canterbury Festival

CANTERBURY FESTIVAL KENT’S INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL 20 OCT - 3 NOV 2018 canterburyfestival.co.uk i Welcome & Sponsors Box Office: 01227 787787 canterburyfestival.co.uk WELCOME PARTNER AND PRINCIPAL SPONSOR FUNDERS from Rosie Turner Festival Director Per ardua ad astra (through struggle to the stars) has been our watchword in preparing this Canterbury Christ Church University welcomes the SPONSORS year’s star-studded Festival. opportunity to work with Canterbury Festival in 2018, for the ninth consecutive year. We are delighted to be Massive thanks to our sponsors and associated with such a prestigious and popular event in donors – led by Canterbury Christ the city, as both Principal Sponsor and Partner. Church University – who have stayed Venue Sponsor loyal, increased their commitment, Canterbury Festival plays both a vital role in the city’s or joined us for the first time, proving excellent cultural programme and the UK festival that Canterbury needs, loves and calendar. It brings together the people of Canterbury, deserves a fantastic Festival. Now visitors, and international artists in an annual celebration you can support us by booking early, of arts and culture, which contributes to a prosperous telling your friends, organising a and more vibrant city. This year’s Festival promises to work’s night out… we need to sell be as ambitious and inspirational as ever, with a rich Technical Sponsor more tickets than ever before and and varied programme. there’s lots to tempt you. The University is passionate about, and contributes From Knights and Dames to significantly to, the region’s creative economy. We are performing Socks – please look proud to work closely with a range of local and national through the entire programme as cultural organisations, such as the Canterbury Festival, some of our unique events defy to collectively offer an artistically vibrant, academically simple classification. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

We Are TEN – in This Issue

RVW No.31 NEW 2004 Final 6/10/04 10:36 Page 1 Journal of the No.31 October 2004 EDITOR Stephen Connock RVW (see address below) Society We are TEN – In this issue... and still growing! G What RVW means to me Testimonials by sixteen The RVW Society celebrated its 10th anniversary this July – just as we signed up our 1000 th new members member to mark a decade of growth and achievement. When John Bishop (still much missed), Robin Barber and I (Stephen Connock) came together to form the Society our aim was to widen from page 4 appreciation of RVW’s music, particularly through recordings of neglected but high quality music. Looking back, we feel proud of what we have achieved. G 49th Parallel World premieres Through our involvement with Richard Hickox, and Chandos, we have stimulated many fine world by Richard Young premiere recordings, including The Poisoned Kiss, A Cotswold Romance, Norfolk Rhapsody No.2, page 14 The Death of Tintagiles and the original version of A London Symphony. Our work on The Poisoned Kiss represents a special contribution as we worked closely with Ursula Vaughan Williams on shaping the libretto for the recording. And what beautiful music there is! G Index to Journals 11-29 Medal of Honour The Trustees sought to mark our Tenth Anniversary in a special way and decided to award an International Medal of Honour to people who have made a remarkable contribution to RVW’s music. The first such Award was given to Richard Hickox during the concert in Gloucester and more . -

Dalrev Vol35 Iss2 Pp158 165.Pdf (1.373Mb)

J_ CROSSROADS OF THE NORTH By ALEX. S. MOWAT O one who knows and loves the Orkney and Shetland Islands it is surprising to find how little other people know of them and annoying to discover how often they T are confused with the Hebrides. All three, of course, are groups of islands lying off the coast of Scotland, the He brides to the west, the Orkneys and Shetlands to the north. 'rhey therefore have some geographic and climatic character istics in common. But, despite half a century and more of com pulsory schooling in English applied to all, the inhabitants of ..-; the northern and western isles remain very different in culture and tradition. The Hebrides once spoke only Gaelic and many still speak it as a first language. It is unknown, and always has been, in the Orkneys and Shetlands. The Hebridean is a Celt, a representative of a dying culture, looking back into the gloom and mystery of the Celtic twilight. N osta.lgia for the storied past breathes from his beaches and his shielings. He has loved and lost. The Orkney-man and the Shetlander have neither the inclination nor the time to spend on such nonsense. A shrewd and hardy vigour, descending (they declare) from their Norse an cestors, saves them from any trace of that melancholic lethargy sometimes attributed to the Hebridean Celt. While they are passionately attached to their islands and well versed in their history and tra<litions, they are equally interested in the latest methods of egg-production and tho price of fish at the Aber deen fish market. -

Babel Film Festival 2019 Anna Karina, Il Volto

_ n.3 Anno IX N. 79 | Gennaio 2020 | ISSN 2431 - 6739 Politiche educative e formazione culturale Anna Karina, il volto iconico passato e futuro cinematografica per i giovani in Germania della Nouvelle Vague Danimarca 1940 – Parigi 14 Dicembre 2019 Il cinema educa alla in programma dall'8 di questo mese al 1° mar- vita! zo prossimo. Se n'è andata il 14 dicembre, die- Dopo una visita a fine Novembre a Francoforte ci giorni dopo l'inaugurazione dell'atelier (ben sul Meno di una delegazione di Diari di Cine- successivo alle loro comuni imprese in cop- club, la responsabile delle attività di alfabetiz- pia) di Godard, "Le Studio d'Orphée" alla Fon- zazione del dipartimento di educazione cine- dazione Prada. Aveva appena fatto in tempo matografica del DDF - DeutschesFilminstitut & Bergamo a volerla come ospite d'onore e sog- Filmmuseum, Christine Kopf interviene per getto presente e parlante della propria retro- raccontare la storia e le politiche culturali dell’i- spettiva nella scorsa edizione, come Cannes a stituto di cinema tedesco dedicarle il manifesto e Bologna a... cineritro- varla l'anno precedente. A oltre sessant'anni Nei 124 anni della sua esi- dalla sua esplosione, la nouvelle vague si sta pro- stenza, il cinema ha subi- gressivamente quanto inesorabilmente conge- to cambiamenti incredi- dando. Nella tragedia, col suicidio di Jean Se- bili. Già dalle sfarfallanti berg (1979); nel dramma, con le scomparse brevi sequenze delle pri- premature di Truffaut (‘84) e Demy ('90); per me immagini, quelle che naturale uscita dalla vita, come nei casi di sono state lanciate da Chabrol e Rohmer (2010), più di recente di Ri- proiettori rumorosi sugli Non è riuscita a vedere e a farsi vedere, come vette (2016), Jeanne Moreau (2017) e Agnés schermi di sale fieristi- si attendeva e ci si augurava, alla retrospettiva Varda pochi mesi or sono. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) House of Preposterous Women: Michelle Williams Gamaker Re-Auditions Kanchi Lord, C.; Williams Gamaker, M. Publication date 2019 Document Version Final published version Published in OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Lord, C., & Williams Gamaker, M. (2019). House of Preposterous Women: Michelle Williams Gamaker Re-Auditions Kanchi. OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based, 3, 9-17. https://www.oarplatform.com/house-of-preposterous-women-michelle-williams-gamaker-re- auditions-kanchi/ General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:02 Oct 2021 House of Preposterous Women: Michelle Williams Gamaker re-auditions Kanchi Catherine Lord with Michelle Williams Gamaker To cite this contribution: Lord, Catherine, with Michelle Williams Gamaker.