In the Territory of Auchencrow: Long Continuity Or Late Development in Early Scottish field-Systems? J Donnelly*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military Tribunals Berwick Advertiser 1916

No. SURNAME CHRISTIAN NAME OCCUPATION PLACE DATE OF TRIBUNAL DATE OF NEWSPAPER TRIBUNAL AREA REASON FOR CLAIM RESULT OF TRIBUNAL PRESIDING OFFICER INFO 1 BOYD DAVID Sanitary inspector Berwick 25/02/1916 03/03/1916 BA BERWICK In the national interests, he said his services were indispensible in the interests of the health of the community. Claim refused Mr D. H. W. Askew Employed as the sanitary inspector for the borough of Berwick, he said he was happy to serve if the court decided. There was a long discussion and it was decided that his job could be done by someone unqualified. 2 UNIDENTIFIED UNIDENTIFIED Land agents assistant UNIDENTIFIED 25/02/1916 03/03/1916 BA BERWICK UNIDENTIFIED Temporary exemption granted until 31st May Mr D. H. W. Askew Case heard in private. 3 UNIDENTIFIED UNIDENTIFIED Dentist's assistant UNIDENTIFIED 25/02/1916 03/03/1916 BA BERWICK Indispensible to the business Temporary exemption granted Mr D. H. W. Askew Case heard in private. 4 UNIDENTIFIED UNIDENTIFIED Grocer's assistant UNIDENTIFIED 25/02/1916 03/03/1916 BA BERWICK Domestic hardship Temporary exemption granted until 31st August Mr D. H. W. Askew He had 3 brothers and one sister. His father had died 2 years before the war. One brother had emigrated to New Zealand and had been declared as unfit for service, another had emigrated to Canada and was currently serving in France, and the other brother had served in the territorial army, went to France to serve and had been killed. His only sister had died just before the war, he said he was willing to serve, but his mother did not want him to go, having lost one son 5 UNIDENTIFIED UNIDENTIFIED UNIDENTIFIED UNIDENTIFIED 25/02/1916 03/03/1916 BA BERWICK Domestic hardship Temporary exemption granted until 31st August Mr D. -

34 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

34 bus time schedule & line map 34 Berwick upon Tweed - Duns View In Website Mode The 34 bus line (Berwick upon Tweed - Duns) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Duns: 7:29 AM - 2:40 PM (2) Tweedmouth: 8:52 AM - 3:52 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 34 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 34 bus arriving. Direction: Duns 34 bus Time Schedule 44 stops Duns Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:29 AM - 2:40 PM Retail Park, Tweedmouth Tuesday 7:29 AM - 2:40 PM Asda, Tweedmouth Main Street, Spittal Wednesday 7:29 AM - 2:40 PM Union Brae, Tweedmouth Thursday 7:29 AM - 2:40 PM Friday 7:29 AM - 2:40 PM Golden Square, Berwick-Upon-Tweed Saturday 7:29 AM - 2:40 PM Castlegate Red Lion, Berwick-Upon-Tweed 11B Castlegate, Berwick-upon-Tweed Castlegate, Berwick-Upon-Tweed 34 bus Info North Road Nursing Home, Berwick-Upon-Tweed Direction: Duns Stops: 44 Cemetery Lodge, Berwick-Upon-Tweed Trip Duration: 60 min Line Summary: Retail Park, Tweedmouth, Asda, Morrisons, Newƒelds Tweedmouth, Union Brae, Tweedmouth, Golden Square, Berwick-Upon-Tweed, Castlegate Red Lion, Berwick-Upon-Tweed, Castlegate, Berwick-Upon- Conundrum, Ramparts Business Park Tweed, North Road Nursing Home, Berwick-Upon- Tweed, Cemetery Lodge, Berwick-Upon-Tweed, Loughend, Marshall Meadows Morrisons, Newƒelds, Conundrum, Ramparts Business Park, Loughend, Marshall Meadows, New New East Farm, Marshall Meadows East Farm, Marshall Meadows, Maryƒeld Bridge, Lamberton, East Flemington, Burnmouth, Lawƒeld Maryƒeld -

Border Brains Walks Berwickshire Border Brains Walks Introduction

Border Brains Walks Berwickshire Border Brains Walks Introduction Welcome to Border Brains Walks: your free guide to exploring the lives and ideas of the Berwickshire geniuses David Hume, James Hutton, Duns Scotus, James Small and Alexander Dow, in the beautiful landscape that gave them birth. The world’s great minds have given us many good reasons to step outside for a walk and a think. Walking was William Hazlitt’s university: “Give me the clear blue sky over my head, and the green turf beneath my feet, a winding road before me, and a three hours’ march to dinner – and then to thinking!” wrote the essayist in On Going a Journey. Berwickshire’s own David Hume, the philosopher, successfully petitioned Edinburgh Town Council to create on Calton Hill Britain’s first recreational walk, entirely dedicated to the public’s healthy pursuits and living. “A circulatory foot road,” he argued, “would present strangers with the most advantageous views of the city … and contribute not only to the pleasure and amusement, but also to the health of the inhabitants of this crowded city.” In this urgent age, we must work hard to find spaces of time to walk or ride a horse or bicycle, to gather our wits and sense our passage over the earth. According to an Arab proverb, the human soul can only travel as fast as a camel can trot. “Modern travelling is not travelling at all,” thought the poet and artist John Ruskin: “it is merely being sent to a place, and very little different from becoming a parcel. -

Scottish Borders (Page 1)

ESSENCE OF SCOTLAND Scottish Borders Front cover: Neidpath Castle, by Peebles This page: Jedburgh Abbey At the southern gateway to Scotland, the seductive Borders region is a land of strong traditions and inspiring heritage sites, a consequence of its turbulent history. A walk through the rolling scenery here is a walk through time, where gardens and abbeys, textile mills and ancient festivals all form part of the patchwork of local life. Cockburnspath 7 Ecclaw 26 BASE YOURSELF IN LOCATION MAP A1107 St Abbs Granthouse A1 Eyemouth Jedburgh Auchencrow Kelso A6105 Duns 4 Paxton welcome Melrose Paid Entry Seasonal Disabled Access Dogs Allowed Tea-Room Gift Shop WC Polwarth A6112 £ Westruther DON’T MISS Swinton Peebles Lauder Ladykirk A7 22 d e A68 A6089 e w A703 Stow T er Gordon Eccles A697 iv Peebles 5 6 A6105 R To find out more about Stichill Coldstream Stobo 1 Earlston 24 12 A72 Galashiels accommodation in these areas, Innerleithen 16 17 14 Kelso 2 Melrose 23 call 0845 22 55 121 3 8 Dryburgh 3 Newtown 3 A699 11 or click on visitscotland.com St Boswells St Boswells A698 Kirk Yetholm A708 Selkirk Cappercleuch 1. Traquair House, near 2. Floors Castle in Kelso is 3. The Scottish Borders 4. Paxton House by 5. Glentress Forest lies 3 Jedburgh 1 25 Innerleithen, dates back to the home of the Roxburghe have four truly amazing Berwick-upon-Tweed was just 1/2 miles to the east of Oxnam A698 Denholm IDEAL FOR Hawick A68 the 12th century and is said family and is the largest abbeys in Jedburgh, Kelso, built in 1758 for Patrick Peebles and is ideal for Ettrick to be the oldest continuously inhabited castle in Scotland. -

Launch of the James Hutton Trail in the Scottish Borders by Mike

C:\Documents and Settings\adixon\Local Settings\Temporary Internet Files\Content.Outlook\7NFVY2G5\maebEdited Launch of the James Hutton Trail.doc Launch of the James Hutton Trail in the Scottish Borders By Mike Browne & Jim Floyd British Geological Survey & Lothian and Borders RIGS Group On the morning of 23 rd May, The Borders Foundation for Rural Sustainability, launched their Scottish Borders James Hutton Trail and the permanent James Hutton Exhibition at the Reiver Farm Shop at Auchencrow near Reston in Berwickshire. With local television and national press coverage, the exhibition and trail were opened by the inimitable Professor Aubrey Manning. This substantial interpretive project has been long awaited by many keen to see the life and work of the ‘father of modern geology’ being celebrated and interpreted in his local area, and at the locations in the Borders made famous by his brilliant geological insights. The project has produced a series of interpretive panels with an accompanying trail leaflet and a developing web site (www.james- hutton.org.uk). One of the panels is at Hutton’s farm at Slighhouses Farm south of Grantshouse, with another at its old marl pit, where Hutton extracted marl in effort at agricultural improvements on the farm. A board has also been placed at his hill farm at Nether Monynut in the Lammermuir Hills. Another panel is located above the classic unconformity section at Siccar Point, a site long overdue for interpretation. For those of us who have long thought access was difficult even to the top of the 60 m high steep and grassy bank above the internationally famous Siccar Point, there is now a way-marked trail to the site from the lane leading to Drysdale’s Turnip Factory, the former access route to Siccar. -

Coldingham with Durham Refs

SYLLABUS OF SCOTTISH CARTULARIES NORTH DURHAM (COLDINGHAM) Raine’s North Durham , Appendix (London, 1852) Compiled by WWS, checked by MHH. A Note on Dating Dating the Coldingham charters can be as much of an art as a science. Although documents begin to be self-dated from about the middle of the thirteenth century (especially records of what happened in the prior’s court) it is rare to find such information for the twelfth century and first thirty years of the thirteenth. Dating therefore has to rely first (and often last) on the known spells in office of eg bishops, abbots, priors and other clerics. The standard reference books, shown in the list of printed sources, have been used for these. Even this is not foolproof. The early thirteenth-century priors of Coldingham are anything but precisely dated and some of the acta of Bertram prior of Durham could be placed anywhere within his known dates of 1189/90 - 1212/13. After c. 1200, the acta of the bishops of St Andrews are much more helpful. For laymen, the position is often more obscure, except for kings and earls. Even justiciars and sheriffs are sometimes poorly recorded. With lesser figures things get trickier. After c. 1250, it is possible to show floruits of many of the major tenants of Coldingham. Before then, a list of 1235 of the tenants gives some help for that decade. Beyond that, it is possible to work out rough and ready family trees for many of the occupiers of lands and hence to produce rough and ready lines of succession and floruits. -

Download Original Attachment

Property Reference Number Primary Liable party name Full Property Address 100043001 Trs Of Abbey St Bathans Village Hall Village Hall, Abbey St Bathans, Duns, TD11 3TX 101001001 The Leonard Cheshire Foundation , Netherbyres House, Ayton, Eyemouth, TD14 5SE 101020702 Easy Lay Flooring Company Workshop, , Ayton Mains, Ayton, Eyemouth, TD14 5RE 101030512 J & D Cook Properties Ltd Training Centre, West Flemington, Eyemouth, TD14 5SQ 101056101 Eyemouth International Sailing Craft Assoc'N Ltd Store, Gunsgreenhill, Eyemouth, TD14 5SF 101056207 Eyemouth International Sailing Craft Assoc'N Ltd .Store, Gunsgreenhill, Eyemouth, TD14 5SF 101056302 Eyemouth International Sailing Craft Assoc'N Ltd Stores, Gunsgreenhill, Eyemouth, Berwickshire, TD14 5SF 101066725 Scottish Borders Council Eyemouth High School, Gunsgreenhill, Eyemouth, TD14 5LZ 101066776 Scottish Borders Council Civic Amenity Site, Gunsgreenhill, Eyemouth, Berwickshire, TD14 5SF 101066804 Scottish Water Sewage Works, , Gunsgreen, Eyemouth, TD14 5LH 101077011 Burnmouth Harbour Trustees Store 1, Burnmouth Harbour, Eyemouth, TD14 5SG 101077022 Burnmouth Harbour Trustees Store 2, Burnmouth Harbour, Eyemouth, TD14 5SG 101077033 Burnmouth Harbour Trustees Store 3, Burnmouth Harbour, Eyemouth, TD14 5SG 101077044 Burnmouth Harbour Trustees Store 4, Burnmouth Harbour, Eyemouth, TD14 5SG 101077055 Burnmouth Harbour Trustees Store 5, Burnmouth Harbour, Eyemouth, TD14 5SG 101077066 Burnmouth Harbour Trustees Store 6, Burnmouth Harbour, Eyemouth, TD14 5SG 101099003 Intensacare Ltd - In Liquidation -

Community Council Resilient Community Plan Ready in Your Community Contents Reston & Auchencrow Community Council

reston & auchencrow community council Resilient Community Plan Ready in youR Community Contents Reston & auChencrow Community CounCil 1. Resilient Communities 3 2. OveRview of PRofile 6 3. Area 8 4. Data Zone 9 5. Flood event maPs 1 in 200 yeaRs 10 6. FiRst PRioRity GRittinG maP 13 7. Risk assessment 14 CONTACts 15 useful infoRmation 19 HOUSEHOLD emeRGenCy Plan 21 aPPendix 1 - Residents’ Questionnaire on the development of a Community Council Resilient Community Plan 23 aPPendix 2 - example Community emergency Group emergency meeting agenda 25 woRkinG in PaRtneRshiP with 2 | RESTON & AuchENcROw cOmmuNiTy cOuNcil | resilient community plan RESiliENT cOmmuNiTiES | overview of profile | area | data zone flood event | first priority gritting | risk assessment | contacts Reston & auChencrow Community CounCil 1. Resilient Communities 1.1 what is a Resilient Community? Resilient Communities is an initiative supported by local, scottish, and the UK Governments, the principles of which are, communities and individuals harnessing and developing local response and expertise to help themselves during an emergency in a way that complements the response of the emergency responders. Emergencies happen, and these can be severe weather, floods, fires, or major incidents involving transport etc. Preparing your community and your family for these types of events will make it easier to recover following the impact of an emergency. Being aware of the risks that you as a community or family may encounter, and who within your community might be able to assist you, could make your community better prepared to cope with an emergency. Local emergency responders will always have to prioritise those in greatest need during an emergency, especially where life is in danger. -

Torness Nuclear Power Station Off-Site Emergency Plan: Outline Planning Zone (OPZ)

Torness Nuclear Power Station Off-Site Emergency Plan: Outline Planning Zone (OPZ) Torness Nuclear Power Station Outline Planning Zone Plan (OPZ) Prepared by East Lothian Council1 Great Britain has well developed emergency response arrangements and there is no change in radiological risk, which remains extremely low. Great Britain has benefitted from over 60 years of clean and safe nuclear power. REPPIR 2019, updated legislation in 2019, and along with other changes introduced Outline Planning Zones (OPZ), to plan for less likely but more severe emergencies, including unforeseen events. For civil nuclear sites, like Torness Nuclear Power Station, the OPZ has been pre-set at 30km, by regulation 9(1)(a) and schedule 5 of REPPIR-19. OPZ planning is lighter touch than for Detailed Emergency Planning Zones (DEPZ), and does not require capabilities to be in place ready to deploy as is the case for the DEPZ. This plan is an overview of the area between the 3km DEPZ and the boundary of the 30km OPZ, detailing the population in this area and in particular the most vulnerable. This plan further improves the already significant emergency response planning in place for Torness Nuclear Power Station. This plan should be read in conjunction with the East Lothian Council (ELC), Torness Nuclear Emergency Response plan which describes the detailed arrangements made for responding to off-site nuclear emergencies. This plan can be found on Resilience Direct and for public consumption on the ELC website with hard copies available at local libraries. 1 Any changes to this plan should be sent to [email protected] 1 Version 1.0 Torness OPZ plan released 2nd November 2020. -

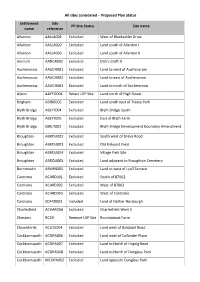

All Sites Considered – Proposed Plan Status

All sites considered – Proposed Plan Status Settlement Site PP Site Status Site name name reference Allanton AALLA001 Excluded West of Blackadder Drive Allanton AALLA002 Excluded Land south of Allanton I Allanton AALLA003 Excluded Land south of Allanton II Ancrum AANCR002 Excluded Dick's Croft II Auchencrow AAUCH001 Excluded Land to west of Auchencrow Auchencrow AAUCH002 Excluded Land to east of Auchencrow Auchencrow AAUCH003 Excluded Land to north of Auchencrow Ayton AAYTO004 Retain LDP Site Land north of High Street Birgham ABIRG005 Excluded Land south east of Treaty Park Blyth Bridge ABLYT004 Excluded Blyth Bridge South Blyth Bridge ABLYT005 Excluded East of Blyth Farm Blyth Bridge SBBLY002 Excluded Blyth Bridge Development Boundary Amendment Broughton ABROU002 Excluded South west of Dreva Road Broughton ABROU003 Excluded Old Kirkyard Field Broughton ABROU004 Excluded Village Park Site Broughton ABROU005 Excluded Land adjacent to Broughton Cemetery Burnmouth ABURN005 Excluded Land to west of Lyall Terrace Cardrona ACARD001 Excluded South of B7062 Cardrona ACARD002 Excluded West of B7062 Cardrona ACARD003 Excluded West of Cardrona Cardrona SCARD002 Included Land at Nether Horsburgh Charlesfield ACHAR004 Excluded Charlesfield West II Chesters RC2B Remove LDP Site Roundabout Farm Clovenfords ACLOV004 Excluded Land west of Bowland Road Cockburnspath ACOPA006 Excluded Land west of Callander Place Cockburnspath ACOPA007 Excluded Land to North of Hoprig Road Cockburnspath ACOPA008 Excluded Land to North of Dunglass Park Cockburnspath MCOPA002 -

Specialist Service 2 Man Delivery Postcode Limitations

Whilst our Next Day Delivery service covers most locations, we currently have some restricted areas affecting the extremities of England and Wales where we are unable to offer a 24hr service – please check at the point of ordering with us to confirm availability in your area. We are working on programmes to continually improve our coverage in future, so please check back with us on a regular basis as more areas are extended to be within next day catchment. Specialist Service 2 Man Delivery Postcode Limitations Postcode Name Service Earliest Time CA1 Carleton, Cumbria Tuesday and Thursday only CA10 Askham, Cumbria Tuesday and Thursday only CA11 Blencow, Cumbria Tuesday and Thursday only 930am CA12 Applethwaite, Cumbria Tuesday and Thursday only 930am CA13 Bewaldeth, Cumbria Tuesday and Thursday only 930am CA14 Asby, Cumbria Tuesday and Thursday only 930am CA15 Allonby, Cumbria Tuesday and Thursday only 930am CA16 Appleby-in-Westmorland, Cumbria Tuesday and Thursday only 930am CA17 Brough Sowerby, Cumbria Tuesday and Thursday only CA18 Broad Oak, Cumbria Tuesday and Thursday only CA19 Beckfoot, Cumbria Tuesday and Thursday only CA2 Cummersdale, Cumbria Tuesday and Thursday only CA20 Calder Bridge, Cumbria Tuesday and Thursday only CA21 Beckermet, Cumbria Tuesday and Thursday only CA22 Egremont, Cumbria Tuesday and Thursday only CA23 Cleator, Cumbria Tuesday and Thursday only CA24 Moor Row, Cumbria Tuesday and Thursday only CA25 Cleator Moor, Cumbria Tuesday and Thursday only CA26 Arlecdon, Cumbria Tuesday and Thursday only CA27 St Bees, -

Novuspublish Nexus Normal

Berwick upon Tweed - Duns/ Berwickshire High School 34 Effective from: 11/08/2020 Travelsure: 01668 219 291 Tweedmouth, RetailBerwick, Park Golden SquareBurnmouth, VillageEyemouth, Albert Eyemouth,Road High StreetAyton, Bank Reston, BonchesterAuchencrow, Bridge oppPreston Craw Inn , Village HallDuns, Market Square South St Approx. 5 15 20 22 30 35 43 53 60 journey times Monday to Friday Tweedmouth, Retail Park 0729 1025 1225 1440 Berwick, Golden Square 0734 1030 1230 1445 Burnmouth, A1 northbound 0744 Ayton, Bank 0749 Burnmouth, Village 1040 1240 1455 Eyemouth, Albert Road 0757 1045 1245 1500 Coldingham, nr Strathtyre House 0805 Eyemouth, High Street 1047 1247 1502 Ayton, Bank 1055 1255 1510 Reston, Bonchester Bridge 0812 1100 1300 1515 Auchencrow, opp Craw Inn 0820 1108 1308 1523 Preston , Village Hall 0830 1118 1318 1533 Duns, Market Square South St 0837 1125 1325 1540 Berwickshire High School 0842 .... .... .... Berwick upon Tweed - Duns/ Berwickshire High School 34 Effective from: 11/08/2020 Travelsure: 01668 219 291 Saturday Tweedmouth, Retail Park 0729 1025 1225 1440 Berwick, Golden Square 0734 1030 1230 1445 Burnmouth, A1 northbound 0744 Ayton, Bank 0749 Burnmouth, Village 1040 1240 1455 Eyemouth, Albert Road 0757 1045 1245 1500 Coldingham, nr Strathtyre House 0805 Eyemouth, High Street 1047 1247 1502 Ayton, Bank 1055 1255 1510 Reston, Bonchester Bridge 0812 1100 1300 1515 Auchencrow, opp Craw Inn 0820 1108 1308 1523 Preston , Village Hall 0830 1118 1318 1533 Duns, Market Square South St 0837 1125 1325 1540 Berwickshire High School