The Socio-Hydrology of Smallholders in Marathwada, Maharashtra State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2011-12 Summary

Dr.YSRHU, Annual Report, 2011-12 Published by Dr.YSR Horticultural University Administrative Office, P.O. Box No. 7, Venkataramannagudem-534 101, W.G. Dist., A.P. Phones : 08818-284312, Fax : 08818-284223 E-mail : [email protected], [email protected] URL : www.drysrhu.edu.in Compiled and Edited by Dr. B. Srinivasulu, Registrar & Director of Research (FAC), Dr.YSRHU Dr. M.B.Nageswararao, Director of Extension, Dr.YSRHU Dr. M.Lakshminarayana Reddy, Dean of Horticulture, Dr.YSRHU Dr. D.Srihari, Dean of Student Affairs & Dean PG Studies, Dr.YSRHU Lt.Col. P.R.P. Raju, Estate Officer, Dr.YSRHU Dr.B.Prasanna Kumar, Deputy COE, Dr.YSRHU All rights are reserved. No part of this book shall be reproduced or transmitted in any form by print, microfilm or any other means without written permission of the Vice-Chancellor, Dr.Y.S.R. Horticultural University, Venkataramannagudem. Printed at Dr.C.V.S.K.SARMA, I.A.S. VICE-CHANCELLOR Dr.Y.S.R. Horticultural University & Agricultural Production Commissioner & Principal Secretary to Government, A.P. I am happy to present the Fourth Annual Report of Dr.Y.S.R. Horticultural University (Dr.YSRHU). It is a compiled document of the university activities during the year 2011-12. Dr.YSR Horticultural University was established at Venkataramannagudem, West Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh on 26th June, 2007. Dr.YSR Horticultural University second of its kind in the country, with the mandate for Education, Research and Extension related to horticulture and allied subjects. The university at present has 4 Horticultural Colleges, 5 Polytechnics, 25 Research Stations and 3 KVKs located in 9 agro-climatic zones of the state. -

C6431029320.Pdf

International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology (IJEAT) ISSN: 2249 – 8958, Volume-9 Issue-3, February, 2020 Estimation of Water Balance Components of Watersheds in the Manjira River Basin using SWAT Model and GIS Akshata Mestry, Raju Narwade, Karthik Nagarajan Abstract: This study mainly focus on hydrological behavior of The study area includes two watersheds from Manar stream watersheds in The Manjira River basin using soil and water (watershed code-MNJR008 and MNJR011) [19]. These assessment tool (SWAT) and Geographical information system watersheds come under Manjira river which is the tributary (GIS). The water balance components for watersheds in the of India’s second largest river Godavari and flows through Manjira River were determined by using SWAT model and GIS. some parts of Marathwada region. The various GIS data Determination of these water balance components helps to study direct and indirect factors affecting characteristics of selected such as soil data, LU/LC, DEM used as inputs in SWAT to watersheds. Manjira River contains total 28 watersheds among determine water balance components of study area. The them 2 were selected having watershed code as MNJR008 and water balancing components helps in water budgeting, gives MNJR011 specified by the Central Ground Water Board. The brief idea about watershed characteristics, this further can be SWAT input data such as Digital elevation model (DEM), land used to predict the availability of water and so can help in use and land cover (LU/LC), Soil classification, slope and water resource management.[14] weather data was collected. Using these inputs in SWAT the different water balancing components such as rainfall, baseflow, II. -

Summary Report on Water Use Efficiency Studies for 35 Irrigation Projects

Summary Report On Water Use Efficiency Studies For 35 Irrigation Projects Organized by Performance Overview & Management Improvement Organization Central Water Commission Government of India February, 2016 1 Contents S.No TITLE Page No Prologue 3 I Abbreviations 4 II SUMMARY OF WUE STUDIES 5 ANDHRA PRADESH 1 Bhairavanthippa Project 6-7 2 Gajuladinne (Sanjeevaiah Sagar Project) 8-11 3 Gandipalem project 12-14 4 Godavari Delta System (Sir Arthur Cotton Barrage) 15-19 5 Kurnool-Cuddapah Canal System 20-22 6 Krishna Delta System(Prakasam Barrage) 23-26 7 Narayanapuram Project 27-28 8 Srisailam (Neelam Sanjeeva Reddy Sagar Project)/SRBC 29-31 9 Somsila Project 32-33 10 Tungabadhra High level Canal 34-36 11 Tungabadhra Project Low level Canal(TBP-LLC) 37-39 12 Vansadhara Project 40-41 13 Yeluru Project 42-44 ANDHRA PRADESH AND TELANGANA 14 Nagarjuna Sagar project 45-48 TELANGANA 15 Kaddam Project 49-51 16 Koli Sagar Project 52-54 17 NizamSagar Project 55-57 18 Rajolibanda Diversion Scheme 58-61 19 Sri Ram Sagar Project 62-65 20 Upper Manair Project 66-67 HARYANA 21 Augmentation Canal Project 68-71 22 Naggal Lift Irrigation Project 72-75 PUNJAB 23 Dholabaha Dam 76-78 24 Ranjit Sagar Dam 79-82 UTTAR PRADESH 25 Ahraura Dam Irrigation Project 83-84 26 Walmiki Sarovar Project 85-87 27 Matatila Dam Project 88-91 28 Naugarh Dam Irrigation Project 92-93 UTTAR PRADESH & UTTRAKHAND 29 Pilli Dam Project 94-97 UTTRAKHAND 30 East Baigul Project 98-101 BIHAR 31 Kamla Irrigation project 102-104 32 Upper Morhar Irrigation Project 105-107 33 Durgawati Irrigation -

Government of Karnataka Watershed Development Department Public Disclosure Authorized

Government of Karnataka Watershed Development Department Public Disclosure Authorized Sujala-II Watershed Project The World Bank Assisted Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental Management Framework Public Disclosure Authorized Final Report December 2011 Public Disclosure Authorized Samaj Vikas Development Support Organisation Hyderabad www.samajvikas.org Government of Karnataka – Watershed Development Department – The World Bank Assisted Sujala-II Environmental Management Framework – Final Report – December 2011 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. 6 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 13 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................ 13 1.2 Sujala-II Project ...................................................................................................... 14 1.2.1 Project Development Objective ................................................................. 14 1.2.2 Project Location and Beneficiaries ............................................................ 14 1.2.3 Project Phasing ............................................................................................. 15 1.3 Project Design and Brief Description of Sujala-II ............................................. 15 1.3.1 Component 1: Support for Improved Program Integration in Rainfed -

Major Dams in India

Major Dams in India 1. Bhavani Sagar dam – Tamil Nadu It came into being in 1955 and is built on the Bhavani River. This is the largest earthen dam in India and South Asia and the second-largest in the world. It is in Sathyamangalam district of Tamil Nadu and comes under the Tamil Nadu government. It is 130 ft tall and 8.4 km long with a capacity of 8 megawatts. 2. Tehri Dam – Uttarakhand It is the highest dam in India and comes under the top 10 highest dams in the world. This came into being in 2006 and stands tall on the Bhagirathi river. It is in the Tehri district of Uttarakhand and comes under National Thermal Power Corporation Limited. It is an embankment dam with a height of 855 ft and a length of 1,886 ft. 3. Hirakud dam – Odisha It came into being in 1957 and stands tall on the Mahanadi river. It is one of the first major multipurpose river valley projects in India. This is a composite dam and reservoir and is in the city of Sambalpur in Odisha. It comes under the government of Odisha. It is 200 ft tall and 55 km long and is the longest Dam in India. 4. Bhakra Nangal Dam – Himachal Pradesh It came into being in 1963 and stands tall on the Sutlej river. This is the third-largest reservoir in India and is in Bilaspur district of Himachal Pradesh. It is a concrete gravity dam and comes under the state government of Himachal Pradesh. -

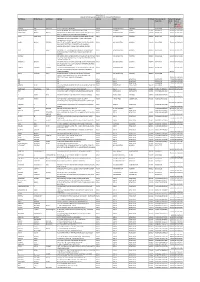

First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Country State

Biocon Limited Amount of unclimed and unpaid Interim dividend for FY 2010-11 First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Amount Proposed Securities Due(in Date of Rs.) transfer to IEPF (DD- MON-YYYY) JAGDISH DAS SHAH HUF CK 19/17 CHOWK VARANASI INDIA UTTAR PRADESH VARANASI BIO040743 150.00 03-JUN-2018 RADHESHYAM JUJU 8 A RATAN MAHAL APTS GHOD DOD ROAD SURAT INDIA GUJARAT SURAT 395001 BIO054721 150.00 03-JUN-2018 DAMAYANTI BHARAT BHATIA BNP PARIBASIAS OPERATIONS AKRUTI SOFTECH PARK ROAD INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO001163 150.00 03-JUN-2018 NO 21 C CROSS ROAD MIDC ANDHERI E MUMBAI JYOTI SINGHANIA CO G.SUBRAHMANYAM, HEAD CAP MAR SER IDBI BANK LTD, INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO011395 150.00 03-JUN-2018 ELEMACH BLDG PLOT 82.83 ROAD 7 STREET NO 15 MIDC, ANDHERI EAST, MUMBAI GOKUL MANOJ SEKSARIA IDBI LTD HEAD CAPITAL MARKET SERVIC CPU PLOT NO82/83 INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO017966 150.00 03-JUN-2018 ROAD NO 7 STREET NO 15 OPP SPECIALITY RANBAXY LABORATORI ES MIDC ANDHERI (E) MUMBAI-4000093 DILIP P SHAH IDBI BANK, C.O. G.SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD CAP MARK SERV INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO022473 150.00 03-JUN-2018 PLOT 82/83 ROAD 7 STREET NO 15 MIDC, ANDHERI.EAST, MUMBAI SURAKA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAMANYAM HEAD CAPITAL MKT SER INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO043568 150.00 03-JUN-2018 C P U PLOT NO 82/83 ROAD NO 7 ST NO 15 OPP RAMBAXY LAB ANDHERI MUMBAI (E) RAMANUJ MISHRA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD CAP MARK SERV INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO047663 150.00 03-JUN-2018 -

List of Dams and Reservoirs in India 1 List of Dams and Reservoirs in India

List of dams and reservoirs in India 1 List of dams and reservoirs in India This page shows the state-wise list of dams and reservoirs in India.[1] It also includes lakes. Nearly 3200 major / medium dams and barrages are constructed in India by the year 2012.[2] This list is incomplete. Andaman and Nicobar • Dhanikhari • Kalpong Andhra Pradesh • Dowleswaram Barrage on the Godavari River in the East Godavari district Map of the major rivers, lakes and reservoirs in • Penna Reservoir on the Penna River in Nellore Dist India • Joorala Reservoir on the Krishna River in Mahbubnagar district[3] • Nagarjuna Sagar Dam on the Krishna River in the Nalgonda and Guntur district • Osman Sagar Reservoir on the Musi River in Hyderabad • Nizam Sagar Reservoir on the Manjira River in the Nizamabad district • Prakasham Barrage on the Krishna River • Sriram Sagar Reservoir on the Godavari River between Adilabad and Nizamabad districts • Srisailam Dam on the Krishna River in Kurnool district • Rajolibanda Dam • Telugu Ganga • Polavaram Project on Godavari River • Koil Sagar, a Dam in Mahbubnagar district on Godavari river • Lower Manair Reservoir on the canal of Sriram Sagar Project (SRSP) in Karimnagar district • Himayath Sagar, reservoir in Hyderabad • Dindi Reservoir • Somasila in Mahbubnagar district • Kandaleru Dam • Gandipalem Reservoir • Tatipudi Reservoir • Icchampally Project on the river Godavari and an inter state project Andhra pradesh, Maharastra, Chattisghad • Pulichintala on the river Krishna in Nalgonda district • Ellammpalli • Singur Dam -

Irrigation with Wastewater in Andhra Pradesh, India, a Water Balance Evaluation Along Peerzadiguda Canal

UPTEC W05 024 M.Sc. Thesis Wo rk Examensarbete 20 p June 20 05 I rrigation with wastewater in A ndhra Pradesh, India, a water b alance evaluation along P eerzadiguda canal B evattning med avloppsvatten i Andhra P radesh, Indien, en vattenbalansutvärdering l ängs Peerzadiguda kanal _ ______________________________ _ J ulia Hytteborn ABSTRACT Irrigation with wastewater in Andhra Pradesh, India, a water balance evaluation along Peerzadiguda canal Julia Hytteborn This thesis focuses on the amounts of wastewater irrigating the land along Peerzadiguda irrigation canal in Andhra Pradesh, India. The Peerzadiguda irrigation canal is located north of Musi river downstream Hyderabad, the capital of the Indian state Andhra Pradesh. In regions where the freshwater resources are scarce, wastewater can become a valuable resource in irrigated agriculture. This is the case along Musi river that contains Hyderabad’s untreated and partly treated wastewater. The study area is the land around Peerzadiguda irrigation canal that is irrigated with water from the canal. The flow in the irrigation canal was measured, water losses were estimated and the irrigation amount over the whole study area was quantified. In a Geographical Information System (GIS) the size of the study area was measured and a few maps produced. The actual irrigation on a few farms was also calculated from measurements of the irrigation canals on the farms and from data from interviews with the farmers. The irrigation of the fields was preformed with basin irrigation. The values of the actual irrigation was used in water balance calculations of the root zone for the crops growing in the area: vegetable, paragrass and paddy rice. -

In the Supreme Court of India

REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA ORIGINAL JURISDICTION ORIGINAL SUIT NO. 1 OF 2006 State of Andhra Pradesh …… Plaintiff Vs. State of Maharashtra & Ors. …… Defendants WITH WRIT PETITION [C] NO. 134 OF 2006 WRIT PETITION [C] NO. 210 OF 2007 WRIT PETITION [C] NO. 207 OF 2007 AND CONTEMPT PETITION [C] NO. 142 OF 2009 IN ORIGINAL SUIT NO. 1 OF 2006 JUDGMENT R.M. LODHA, J. Original Suit No. 1 of 2006 Two riparian states – Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra – of the inter-state Godavari river are principal parties in the suit filed under Article 131 of the Constitution of India read with Order XXIII Rules 1,2 and 3 of the Supreme Court Rules, 1966. The suit has been filed by Andhra Pradesh (Plaintiff) complaining violations by Maharashtra (1st Defendant) of the 1 Page 1 agreements dated 06.10.1975 and 19.12.1975 which were endorsed in the report dated 27.11.1979 containing decision and final order (hereafter to be referred as “award”) and further report dated 07.07.1980 (hereafter to be referred as “further award) given by the Godavari Water Disputes Tribunal (for short, ‘Tribunal’). The violations alleged by Andhra Pradesh against Maharashtra are in respect of construction of Babhali barrage into their reservoir/water spread area of Pochampad project. The other four riparian states of the inter-state Godavari river – Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Orissa have been impleaded as 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th defendant respectively. Union of India is 2nd defendant in the suit. 2. The Godavari river is the largest river in Peninsular India and the second largest in the Indian Union. -

RURAL ENVIRONMENT Runa Sarkar and Bhaskar Chakrabarti

226 India Infrastructure Report 2007 9 RURAL ENVIRONMENT Runa Sarkar and Bhaskar Chakrabarti INTRODUCTION technological solutions to pre-empt environmental degrada- tion, restore, and rejuvenate the degraded environment are Rural environment represents the framework of regulations, discussed further on in the chapter. institutions, and practices in villages defining parameters for the sustainable use of environmental resources while ensuring security of livelihood and a reasonable quality of life. While STATUS OF THE RURAL ENVIRONMENT the scope of environmental infrastructure is often narrowed The ecosystem within which all rural activities are conducted down to the provision of suitable water supply, sewerage, and encompasses the air we breathe, the waterbodies surrounding sanitation systems (Hahn, 2000 and Nunan and Satterthwaite, us, and the land we walk on. Unfettered human activity can 2001), it has within its purview (a) acquisition, protection, compromise the ability of the environment to support our kind, and maintenance of open spaces, (b) clean up and restoration a condition usually referred to as environmental degradation of degraded lands, (c) integration of existing wildlife or habitat and detrimental to our future. India supports approximately resources, (d) sustainable approaches to controlling flooding 16 per cent of the world population and 20 per cent of its and drainage, (e) developing river corridors and coastal areas, livestock on 2.5 per cent of its geographical area, making its and (f) forest management. Rejuvenation of natural resources environment a highly stressed and vulnerable system. The through activation of watersheds, renewal of wastelands along pressure on land has led to soil erosion, waterlogging, salinity, with enhancement of farm productivity, is a component of nutrient depletion, lowering of the groundwater table, and environmental infrastructure that is attaining increasing soil pollution—largely a consequence of thoughtless human importance as expanding anthropogenic activity stresses natural intervention. -

Governance of Intersectoral Reallocation of Water Within The

Governance of Inter-sectoral reallocation of water within the context of Urbanization in Hyderabad, India DISSERTATION Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor rerum agriculturarum (Dr. rer. agr.) Eingereicht an der Lebenswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin von Atoho Jakhalu Präsidentin der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. Sabine Kunst Dekan der Lebenswissenschaftlichen Fakultät Prof. Dr. Bernhard Grimm Gutachter/in: 1. Prof. Dr. Dr. h. c. Konrad Hagedorn 2. Prof. Dr. Christoph Dittrich Datum der Einreichung: 29/06/2017 Datum der Promotion: 9/10/ 2017 https://doi.org/10.18452/20598 Zusammenfassung Der intersektorale Wasserkonflikt zwischen urbaner und agrarischer Wassernutzung in Hyderabad und die Konkurrenz zwischen den Bedürfnissen der Stadt und den Ansprüchen der Landwirtschaft werden verschärft durch willkürliche Verteilungspraktiken, die den offiziellen Zuteilungsrichtlinien oft widersprechen. Übersetzt in die Sprache von Ostrom, gilt die vorliegende Untersuchung der Kernfrage, warum bestimmte praktizierte Regeln (rules-in-use) fortbestehen, obwohl formale Regeln (rules-in-form) im Bereich der Nutzungsrechte an Wasser vorhanden sind. Ostroms Institutional Analysis and Development Framework (IAD) identifiziert exogene Variablen und deren Einfluss auf die Rolle von Institutionen, durch die die Interaktionen und Entscheidungsprozesse von Menschen gestaltet werden. Die Arbeit versucht dementsprechend zu erklären, wie bestehende Institutionen und Governancestrukturen die Interaktionen beteiligter -

Popularization of River Tourism in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana

Volume 5, Issue 5, May – 2020 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology ISSN No:-2456-2165 Popularization of River Tourism in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana Pulla Suresh, Mr. Sam Nirmal, Arpan Roy Institute of Hotel Management, Hyderabad. Abstract:- Rivers play a vital role in the settlements of urbanization, economical transportation and increasing cities. Archaeological survey shows The interest of humans in traveling these are few of the reasons AssakaMahajanapada (700–300 BCE) was an ancient which is pushing the tourism industry to grow. The present kingdom located between the Godavari and Krishna day river based tourism can be traced back to Britishers Rivers in southeastern India. This tradition is been rule. Humans settled near water bodies only because water followed since a long time as it provides a good source of was easily available for agriculture and their daily needs water and food. The rivers are not only are responsible however with passing time humans also started to visit for settlements which later turned in a whole city but these water bodies just to relax and enjoy the beautiful also with modernization humans make the most out of scene. This gave room to small businesses like boating the river and construct various tourist attraction spots across the river, street food carts and eventually sell of or a structure like dam which is built to control the flow tickets to visit/enter few places. Andhra Pradesh and of water also becomes a tourist attraction. Two such Telangana is known for its spicy food and hot climate but areas in India whose history is intricately preserved are the rivers which flow through these states have really Telangana and Andhra Pradesh.