Governance of Intersectoral Reallocation of Water Within The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2011-12 Summary

Dr.YSRHU, Annual Report, 2011-12 Published by Dr.YSR Horticultural University Administrative Office, P.O. Box No. 7, Venkataramannagudem-534 101, W.G. Dist., A.P. Phones : 08818-284312, Fax : 08818-284223 E-mail : [email protected], [email protected] URL : www.drysrhu.edu.in Compiled and Edited by Dr. B. Srinivasulu, Registrar & Director of Research (FAC), Dr.YSRHU Dr. M.B.Nageswararao, Director of Extension, Dr.YSRHU Dr. M.Lakshminarayana Reddy, Dean of Horticulture, Dr.YSRHU Dr. D.Srihari, Dean of Student Affairs & Dean PG Studies, Dr.YSRHU Lt.Col. P.R.P. Raju, Estate Officer, Dr.YSRHU Dr.B.Prasanna Kumar, Deputy COE, Dr.YSRHU All rights are reserved. No part of this book shall be reproduced or transmitted in any form by print, microfilm or any other means without written permission of the Vice-Chancellor, Dr.Y.S.R. Horticultural University, Venkataramannagudem. Printed at Dr.C.V.S.K.SARMA, I.A.S. VICE-CHANCELLOR Dr.Y.S.R. Horticultural University & Agricultural Production Commissioner & Principal Secretary to Government, A.P. I am happy to present the Fourth Annual Report of Dr.Y.S.R. Horticultural University (Dr.YSRHU). It is a compiled document of the university activities during the year 2011-12. Dr.YSR Horticultural University was established at Venkataramannagudem, West Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh on 26th June, 2007. Dr.YSR Horticultural University second of its kind in the country, with the mandate for Education, Research and Extension related to horticulture and allied subjects. The university at present has 4 Horticultural Colleges, 5 Polytechnics, 25 Research Stations and 3 KVKs located in 9 agro-climatic zones of the state. -

C6431029320.Pdf

International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology (IJEAT) ISSN: 2249 – 8958, Volume-9 Issue-3, February, 2020 Estimation of Water Balance Components of Watersheds in the Manjira River Basin using SWAT Model and GIS Akshata Mestry, Raju Narwade, Karthik Nagarajan Abstract: This study mainly focus on hydrological behavior of The study area includes two watersheds from Manar stream watersheds in The Manjira River basin using soil and water (watershed code-MNJR008 and MNJR011) [19]. These assessment tool (SWAT) and Geographical information system watersheds come under Manjira river which is the tributary (GIS). The water balance components for watersheds in the of India’s second largest river Godavari and flows through Manjira River were determined by using SWAT model and GIS. some parts of Marathwada region. The various GIS data Determination of these water balance components helps to study direct and indirect factors affecting characteristics of selected such as soil data, LU/LC, DEM used as inputs in SWAT to watersheds. Manjira River contains total 28 watersheds among determine water balance components of study area. The them 2 were selected having watershed code as MNJR008 and water balancing components helps in water budgeting, gives MNJR011 specified by the Central Ground Water Board. The brief idea about watershed characteristics, this further can be SWAT input data such as Digital elevation model (DEM), land used to predict the availability of water and so can help in use and land cover (LU/LC), Soil classification, slope and water resource management.[14] weather data was collected. Using these inputs in SWAT the different water balancing components such as rainfall, baseflow, II. -

The Socio-Hydrology of Smallholders in Marathwada, Maharashtra State

he socio-hydrology of smallholders in Marathwada, T Maharashtra state [India] Master Thesis Nadja den Besten August 2016 Department Water resources management & Hydrology Master thesis The socio-hydrological situation of smallholders in Marathwada, Maharashtra state (India) by Nadja I. den Besten to obtain the degree of Master of Science at the Delft University of Technology, to be defended publicly on 26th of August, 2016 at 16:00. Student number: 4401646 Project duration: October 1, 2015 – August 1, 2016 Thesis committee: Prof. dr. ir. H.H.G. Savenije, TU Delft Dr. S. Pande, TU Delft, supervisor Dr. D. van Halem TU Delft This thesis is confidential and cannot be made public until August 21, 2016. An electronic version of this thesis is available at . Preface Dear reader, Less than three years ago I started studying Hydrology at the VU University Amsterdam, never imagining that I would end up studying Watermanagement at the Technical University here, in Delft. But here I am. Fortunately this unwanted change lead to an awesome new journey. I have been able to finish all the exams and confronted all the challenges that came along, especially while writing my thesis. I became good friends with Python, which was my biggest challenge and eventually victory. A thesis is one big confrontation with yourself and requires most of all perseverance, that is best sustained by an encouraging environment. There- fore I want to thank my tutor Saket Pande for his patience, guidance and persistence during this year. Bannie, Swoep, Stinkie, Maggie, the rest of the family, and friends for the mental support and encouragements when needed. -

Summary Report on Water Use Efficiency Studies for 35 Irrigation Projects

Summary Report On Water Use Efficiency Studies For 35 Irrigation Projects Organized by Performance Overview & Management Improvement Organization Central Water Commission Government of India February, 2016 1 Contents S.No TITLE Page No Prologue 3 I Abbreviations 4 II SUMMARY OF WUE STUDIES 5 ANDHRA PRADESH 1 Bhairavanthippa Project 6-7 2 Gajuladinne (Sanjeevaiah Sagar Project) 8-11 3 Gandipalem project 12-14 4 Godavari Delta System (Sir Arthur Cotton Barrage) 15-19 5 Kurnool-Cuddapah Canal System 20-22 6 Krishna Delta System(Prakasam Barrage) 23-26 7 Narayanapuram Project 27-28 8 Srisailam (Neelam Sanjeeva Reddy Sagar Project)/SRBC 29-31 9 Somsila Project 32-33 10 Tungabadhra High level Canal 34-36 11 Tungabadhra Project Low level Canal(TBP-LLC) 37-39 12 Vansadhara Project 40-41 13 Yeluru Project 42-44 ANDHRA PRADESH AND TELANGANA 14 Nagarjuna Sagar project 45-48 TELANGANA 15 Kaddam Project 49-51 16 Koli Sagar Project 52-54 17 NizamSagar Project 55-57 18 Rajolibanda Diversion Scheme 58-61 19 Sri Ram Sagar Project 62-65 20 Upper Manair Project 66-67 HARYANA 21 Augmentation Canal Project 68-71 22 Naggal Lift Irrigation Project 72-75 PUNJAB 23 Dholabaha Dam 76-78 24 Ranjit Sagar Dam 79-82 UTTAR PRADESH 25 Ahraura Dam Irrigation Project 83-84 26 Walmiki Sarovar Project 85-87 27 Matatila Dam Project 88-91 28 Naugarh Dam Irrigation Project 92-93 UTTAR PRADESH & UTTRAKHAND 29 Pilli Dam Project 94-97 UTTRAKHAND 30 East Baigul Project 98-101 BIHAR 31 Kamla Irrigation project 102-104 32 Upper Morhar Irrigation Project 105-107 33 Durgawati Irrigation -

Government of Karnataka Watershed Development Department Public Disclosure Authorized

Government of Karnataka Watershed Development Department Public Disclosure Authorized Sujala-II Watershed Project The World Bank Assisted Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental Management Framework Public Disclosure Authorized Final Report December 2011 Public Disclosure Authorized Samaj Vikas Development Support Organisation Hyderabad www.samajvikas.org Government of Karnataka – Watershed Development Department – The World Bank Assisted Sujala-II Environmental Management Framework – Final Report – December 2011 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. 6 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 13 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................ 13 1.2 Sujala-II Project ...................................................................................................... 14 1.2.1 Project Development Objective ................................................................. 14 1.2.2 Project Location and Beneficiaries ............................................................ 14 1.2.3 Project Phasing ............................................................................................. 15 1.3 Project Design and Brief Description of Sujala-II ............................................. 15 1.3.1 Component 1: Support for Improved Program Integration in Rainfed -

Major Dams in India

Major Dams in India 1. Bhavani Sagar dam – Tamil Nadu It came into being in 1955 and is built on the Bhavani River. This is the largest earthen dam in India and South Asia and the second-largest in the world. It is in Sathyamangalam district of Tamil Nadu and comes under the Tamil Nadu government. It is 130 ft tall and 8.4 km long with a capacity of 8 megawatts. 2. Tehri Dam – Uttarakhand It is the highest dam in India and comes under the top 10 highest dams in the world. This came into being in 2006 and stands tall on the Bhagirathi river. It is in the Tehri district of Uttarakhand and comes under National Thermal Power Corporation Limited. It is an embankment dam with a height of 855 ft and a length of 1,886 ft. 3. Hirakud dam – Odisha It came into being in 1957 and stands tall on the Mahanadi river. It is one of the first major multipurpose river valley projects in India. This is a composite dam and reservoir and is in the city of Sambalpur in Odisha. It comes under the government of Odisha. It is 200 ft tall and 55 km long and is the longest Dam in India. 4. Bhakra Nangal Dam – Himachal Pradesh It came into being in 1963 and stands tall on the Sutlej river. This is the third-largest reservoir in India and is in Bilaspur district of Himachal Pradesh. It is a concrete gravity dam and comes under the state government of Himachal Pradesh. -

Chemical and Chemical Characteristics of Manjeera Water

8 X October 2020 https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2020.31928 International Journal for Research in Applied Science & Engineering Technology (IJRASET) ISSN: 2321-9653; IC Value: 45.98; SJ Impact Factor: 7.429 Volume 8 Issue X Oct 2020- Available at www.ijraset.com Study on the Assessment of Physical, Physico- Chemical and Chemical Characteristics of Manjeera Water Sumera Nazneen1, Nazneen Begum2 1, 2Assistant Professor, Anwarul Uloom College, Mallepally, Hyderabad Abstract: Hyderabad is the capital city of Telangana State in India and is the sixth largest city in India, closely behind Bengaluru. Hyderabad Urban Agglomeration (HUA) is served by a number of natural and man-made water bodies which act as storage for irrigation water, drinking water and groundwater recharge (Chigurupati and Manikonda, 2007). The current water supply sources for Hyderabad and the surrounding areas include Osman Sagar on Musi River, Manjira Barrage on Manjira River, Himayat Sagar on Esi River, which is a tributary of Musi, Singur Dam on Manjira River and Nagarjuna Sagar on Krishna River (Singh, 2010). Hyderabad, a capital City of Telangana state, geographically situated in land locked arid zone and no perennial river but a seasonal River Musi flowing through it. There are two dams built on the Musi river that are Osman Sagar and Himayat Sagar. Both of the reservoirs constitute the major drinking water sources for Hyderabad. For longer periods, it is the capital city of so many rulers and in long run expanded to the 8500 sq.km in Telangana southern Indian State. There are 400 small and big lakes available in Hyderabad City. -

Hyderabad Water-Waste Portraits

HYDERABAD THE WATER-WASTE PORTRAIT Lying along the southern bank of the Musi river, Hyderabad is the fifth largest metropolis in India. The Musi has turned into the city’s sewer, while the city draws water from sources over 100 km away NALLACHERUVU STP Ranga Reddy Nagar Kukatpally drain Jeedimetla Sanath Nagar Picket drain Yousufguda drain Somajiguda Maradpally Taranaka Yousufguda Osmania University Jubilee Hills Hussain Sagar BANJARA HILLS STP Musheerbad Banjara Hills Banjara drain Secretariat Ashok Nagar Chikkadpally Asifnagar AMBERPET STP Golconda ASIFNAGAR WTP Purana Pool Musi river Musi river NAGOLE Malakpet STP Charminar Sewage pumping station Sewage treatment plant (STP) STP (proposed) Water treatment plant (WTP) Waterways Disposal of sewage Source: Anon 2011, 71-City Water-Excreta Survey, 2005-06, Centre for Science and Environment, New Delhi Note: See page 334 for a more detailed map of water sources 330 ANDHRA PRADESH THE CITY Municipal area 707 sq km Total area (Hyderabad Metropolitan Area) 1,905 sq km Hyderabad Population (2005) 7 million Population (2011), as projected in 2005-06 8.2 million THE WATER Demand he modern city of Hyderabad has a river – but few realise Total water demand as per city agency (HMWSSB) 1,300 MLD that it exists or remember it, given its marginal position in Per capita water demand as per HMWSSB 187 LPCD the city as a water source. The city was founded in 1591 on Total water demand as per CPHEEO @ 175 LPCD 1,216 MLD T Sources and supply the south bank of the Musi, about 6 kilometre (km) south-east of the historic Golconda fort. -

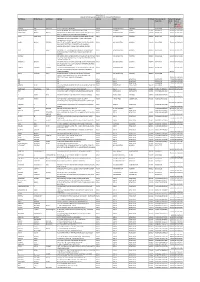

First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Country State

Biocon Limited Amount of unclimed and unpaid Interim dividend for FY 2010-11 First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Amount Proposed Securities Due(in Date of Rs.) transfer to IEPF (DD- MON-YYYY) JAGDISH DAS SHAH HUF CK 19/17 CHOWK VARANASI INDIA UTTAR PRADESH VARANASI BIO040743 150.00 03-JUN-2018 RADHESHYAM JUJU 8 A RATAN MAHAL APTS GHOD DOD ROAD SURAT INDIA GUJARAT SURAT 395001 BIO054721 150.00 03-JUN-2018 DAMAYANTI BHARAT BHATIA BNP PARIBASIAS OPERATIONS AKRUTI SOFTECH PARK ROAD INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO001163 150.00 03-JUN-2018 NO 21 C CROSS ROAD MIDC ANDHERI E MUMBAI JYOTI SINGHANIA CO G.SUBRAHMANYAM, HEAD CAP MAR SER IDBI BANK LTD, INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO011395 150.00 03-JUN-2018 ELEMACH BLDG PLOT 82.83 ROAD 7 STREET NO 15 MIDC, ANDHERI EAST, MUMBAI GOKUL MANOJ SEKSARIA IDBI LTD HEAD CAPITAL MARKET SERVIC CPU PLOT NO82/83 INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO017966 150.00 03-JUN-2018 ROAD NO 7 STREET NO 15 OPP SPECIALITY RANBAXY LABORATORI ES MIDC ANDHERI (E) MUMBAI-4000093 DILIP P SHAH IDBI BANK, C.O. G.SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD CAP MARK SERV INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO022473 150.00 03-JUN-2018 PLOT 82/83 ROAD 7 STREET NO 15 MIDC, ANDHERI.EAST, MUMBAI SURAKA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAMANYAM HEAD CAPITAL MKT SER INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO043568 150.00 03-JUN-2018 C P U PLOT NO 82/83 ROAD NO 7 ST NO 15 OPP RAMBAXY LAB ANDHERI MUMBAI (E) RAMANUJ MISHRA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD CAP MARK SERV INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO047663 150.00 03-JUN-2018 -

Medak District

MEDAK DISTRICT We acknowledge the content from https://medak.telangana.gov.in/ The district derived its name from Medak, the then headquarters town of taluk of the same name. Medak was originally known as Methukudurgam which subsequently changed into Methuku due to the growth of fine and coarse rice in this area. Medak district became part of the Kakatiya Kingdom to the Bahmani Kingdom and later the Golconda Kingdom. Finally, on the fall of the Qutubshahi dynasty, it was annexed to the Mughal Empire. During the formation of Hyderabad State by Asif Jahi, this district was detached and included in the Nizam‟s Dominions. It finally became a part of Andhra Pradesh with effect from 1st November 1956 under the scheme of Re-organisation of States. The early history of Medak district is not very clear. Its political history, however, commences with the advent of the Mouryas who extended their sway to the south during the reign of Asoka. After the Mouryas, the Satavahanas gained prominence over the Deccan of which, Medak district formed a part. Several coins of the Satavahana rulers like Goutamiputra Satakarni, Vasishtiputra Pulumavi, Siv Sri, Yagna Sri Satakarni, etc., were unearthed during excavations at Kondapur village of Medak district. These archeological discoveries indicate the existence of a buried city of vast dimensions with a number of Chaityas, Viharas, Stupas and Monasteries. After the Satavahanas, the district passed under the sway of the Mahisha dynasty. Though as many as eighteen rulers ruled this district for a period of 383 years, only two rulers Mana and Yasa proved to be powerful. -

List of Dams and Reservoirs in India 1 List of Dams and Reservoirs in India

List of dams and reservoirs in India 1 List of dams and reservoirs in India This page shows the state-wise list of dams and reservoirs in India.[1] It also includes lakes. Nearly 3200 major / medium dams and barrages are constructed in India by the year 2012.[2] This list is incomplete. Andaman and Nicobar • Dhanikhari • Kalpong Andhra Pradesh • Dowleswaram Barrage on the Godavari River in the East Godavari district Map of the major rivers, lakes and reservoirs in • Penna Reservoir on the Penna River in Nellore Dist India • Joorala Reservoir on the Krishna River in Mahbubnagar district[3] • Nagarjuna Sagar Dam on the Krishna River in the Nalgonda and Guntur district • Osman Sagar Reservoir on the Musi River in Hyderabad • Nizam Sagar Reservoir on the Manjira River in the Nizamabad district • Prakasham Barrage on the Krishna River • Sriram Sagar Reservoir on the Godavari River between Adilabad and Nizamabad districts • Srisailam Dam on the Krishna River in Kurnool district • Rajolibanda Dam • Telugu Ganga • Polavaram Project on Godavari River • Koil Sagar, a Dam in Mahbubnagar district on Godavari river • Lower Manair Reservoir on the canal of Sriram Sagar Project (SRSP) in Karimnagar district • Himayath Sagar, reservoir in Hyderabad • Dindi Reservoir • Somasila in Mahbubnagar district • Kandaleru Dam • Gandipalem Reservoir • Tatipudi Reservoir • Icchampally Project on the river Godavari and an inter state project Andhra pradesh, Maharastra, Chattisghad • Pulichintala on the river Krishna in Nalgonda district • Ellammpalli • Singur Dam -

Irrigation with Wastewater in Andhra Pradesh, India, a Water Balance Evaluation Along Peerzadiguda Canal

UPTEC W05 024 M.Sc. Thesis Wo rk Examensarbete 20 p June 20 05 I rrigation with wastewater in A ndhra Pradesh, India, a water b alance evaluation along P eerzadiguda canal B evattning med avloppsvatten i Andhra P radesh, Indien, en vattenbalansutvärdering l ängs Peerzadiguda kanal _ ______________________________ _ J ulia Hytteborn ABSTRACT Irrigation with wastewater in Andhra Pradesh, India, a water balance evaluation along Peerzadiguda canal Julia Hytteborn This thesis focuses on the amounts of wastewater irrigating the land along Peerzadiguda irrigation canal in Andhra Pradesh, India. The Peerzadiguda irrigation canal is located north of Musi river downstream Hyderabad, the capital of the Indian state Andhra Pradesh. In regions where the freshwater resources are scarce, wastewater can become a valuable resource in irrigated agriculture. This is the case along Musi river that contains Hyderabad’s untreated and partly treated wastewater. The study area is the land around Peerzadiguda irrigation canal that is irrigated with water from the canal. The flow in the irrigation canal was measured, water losses were estimated and the irrigation amount over the whole study area was quantified. In a Geographical Information System (GIS) the size of the study area was measured and a few maps produced. The actual irrigation on a few farms was also calculated from measurements of the irrigation canals on the farms and from data from interviews with the farmers. The irrigation of the fields was preformed with basin irrigation. The values of the actual irrigation was used in water balance calculations of the root zone for the crops growing in the area: vegetable, paragrass and paddy rice.