Final Reflection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Printing Printout

[Directory] parent nodes: Merge Merges Merge Chain Setting Jumps Notes Trigun [Across the Sands, Dune Hot sands, hot lead, hot blood. Have the hearts of men have shrivled under this alien sun? Thunder] Red Dead Redemption Generic Western Infamous [Appropriate X-Men Metahumans are rare, discriminated against, and pressed into service if they aren't lynched. Measures] Shadow Ops Marvel DC Incredibles City of Heroes [Capes & Spandex] Teen Titans Super heroes are real, but so are villains, and so are monsters. Young Justice Hero Academia PS238 Heroes Path of Exile [Cast Out] You're an outcast, exile, abandoned child of civilization. Welcome to life outside the Golden Empire. Avernum Last Exile Ring of Red [Conflict Long in Wolfenstein Two peoples, united in war against one another. Coming] Killzone Red Faction Naruto Basilisk Kamigawa [Court of War] Kami and Humans both embroiled in complex webs of conflict. Mononokehime Samurai Deeper Kyo Inuyasha Drakengard It's grim, it's dark, it's got magic, demons, monsters, and corrupt nobles and shit. [Darker Fantasy] Berserk I wish there was a Black Company Jump. Diablo 1&2 Nechronica BLAME [Elan Vital] Everything falls apart, even people. But people can sometimes be put back together. Neir: Automata Biomega WoD Mortals Hellgate: London [Extranormal GURPS Monster Hunter Go hunt these things that would prey upon mankind. Forces] Hellboy F.E.A.R. Princess Bride [Fabled Disney Princess Your classic Princess and Prince Charming. Sort of. Coronation] Shrek Love is a Battlefield Platoon Generation Kill War is hell. There is little honor, little glory to be won on the stinking fields of death between the [Fog of War] WW2 (WIP) trenches. -

Japanese Animation Guide: the History of Robot Anime

Commissioned by Japan's Agency for Cultural Affairs Manga, Animation, Games, and Media Art Information Bureau Japanese Animation Guide: The History of Robot Anime Compiled by Mori Building Co., Ltd. 2013 Commissioned by Japan's Agency for Cultural Affairs Manga, Animation, Games, and Media Art Information Bureau Japanese Animation Guide: The History of Robot Anime Compiled by Mori Building Co., Ltd. 2013 Addition to the Release of this Report This report on robot anime was prepared based on information available through 2012, and at that time, with the exception of a handful of long-running series (Gundam, Macross, Evangelion, etc.) and some kiddie fare, no original new robot anime shows debuted at all. But as of today that situation has changed, and so I feel the need to add two points to this document. At the start of the anime season in April of 2013, three all-new robot anime series debuted. These were Production I.G.'s “Gargantia on the Verdurous Planet," Sunrise's “Valvrave the Liberator," and Dogakobo and Orange's “Majestic Prince of the Galactic Fleet." Each was broadcast in a late-night timeslot and succeeded in building fanbases. The second new development is the debut of the director Guillermo Del Toro's film “Pacific Rim," which was released in Japan on August 9, 2013. The plot involves humanity using giant robots controlled by human pilots to defend Earth’s cities from gigantic “kaiju.” At the end of the credits, the director dedicates the film to the memory of “monster masters” Ishiro Honda (who oversaw many of the “Godzilla” films) and Ray Harryhausen (who pioneered stop-motion animation techniques.) The film clearly took a great deal of inspiration from Japanese robot anime shows. -

International Reinterpretations

International Reinterpretations 1 Remakes know no borders… 2 … naturally, this applies to anime and manga as well. 3 Shogun Warriors 4 Stock-footage series 5 Non-US stock-footage shows Super Riders with the Devil Hanuman and the 5 Riders 6 OEL manga 7 OEL manga 8 OEL manga 9 Holy cow, more OEL manga! 10 Crossovers 11 Ghost Rider? 12 The Lion King? 13 Godzilla 14 Guyver 15 Crying Freeman 16 Fist of the North Star 17 G-Saviour 18 Blood: the Last Vampire 19 Speed Racer 20 Imagi Studios 21 Ultraman 6 Brothers vs. the Monster Army (Thailand) The Adventure Begins (USA) Towards the Future (Australia) The Ultimate Hero (USA) Tiga manhwa 22 Dragonball 23 Wicked City 24 City Hunter 25 Initial D 26 Riki-Oh 27 Asian TV Dramas Honey and Clover Peach Girl (Taiwan) Prince of Tennis (Taiwan) (China) 28 Boys Over Flowers Marmalade Boy (Taiwan) (South Korea) Oldboy 29 Taekwon V 30 Super Batman and Mazinger V 31 Space Gundam? Astro Plan? 32 Journey to the West (Saiyuki) Alakazam the Great Gensomaden Saiyuki Monkey Typhoon Patalliro Saiyuki Starzinger Dragonball 33 More “Goku”s 34 The Water Margin (Suikoden) Giant Robo Outlaw Star Suikoden Demon Century Akaboshi 35 Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sangokushi) Mitsuteru Yokoyama’s Sangokushi Kotetsu Sangokushi BB Senshi Sangokuden Koihime Musou Ikkitousen 36 World Masterpiece Theater (23 seasons since 1969) Moomin Heidi A Dog of Flanders 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother Anne of Green Gables Adventures of Tom Sawyer Swiss Family Robinson Little Women Little Lord Fauntleroy Peter -

The Mobile Suit Gundam Franchise

The Mobile Suit Gundam Franchise: a Case Study of Transmedia Storytelling Practices and the Role of Digital Games in Japan Akinori (Aki) Nakamura College of Image Arts and Sciences, Ritsumeikan University 56-1 Toji-in Kitamachi, Kita-ku, Kyoto 603-8577 [email protected] Susana Tosca Department of Arts and Communication, Roskilde University Universitetsvej 1, P.O. Box 260 DK-4000 Roskildess line 1 [email protected] ABSTRACT The present study looks at the Mobile Suit Gundam franchise and the role of digital games from the conceptual frameworks of transmedia storytelling and the Japanese media mix. We offer a historical account of the development of “the Mobile Suit Gundam” series from a producer´s perspective and show how a combination of convergent and divergent strategies contributed to the success of the series, with a special focus on games. Our case can show some insight into underdeveloped aspects of the theory of transmedial storytelling and the Japanese media mix. Keywords Transmedia Storytelling, Media mix, Intellectual Property, Business Strategy INTRODUCTION The idea of transmediality is now more relevant than ever in the context of media production. Strong recognizable IPs take for example more and more space in the movie box office, and even the Producers Guild of America ratified a new title “transmedia producer” in 2010 1. This trend is by no means unique to the movie industry, as we also detect similar patterns in other media like television, documentaries, comics, games, publishing, music, journalism or sports, in diverse national and transnational contexts (Freeman & Gambarato, 2018). However, transmedia strategies do not always manage to successfully engage their intended audiences; as the problematic reception of a number of works can demonstrate. -

Atlantic News

This Page © 2004 Connelly Communications, LLC, PO Box 592 Hampton, NH 03843- Contributed items and logos are © and ™ their respective owners Unauthorized reproduction 30 of this page or its contents for republication in whole or in part is strictly prohibited • For permission, call (603) 926-4557 • AN-Mark 9A-EVEN- Rev 12-16-2004 PAGE 4 SEA | ATLANTIC NEWS | JUNE 16, 2006 | VOL 32, NO 23 ATLANTICNEWS.COM . Brentwood | East Kingston | Exeter | Greenland | Hampton | Hampton Beach | Hampton Falls | Kensington | Newfields | North Hampton | Rye | Rye Beach | Seabrook | South Hampton | Stratham MAILED WEEKLY TO NEARLY 23,000 HOMES!! POSITIVE COMMUNITY AND SCHOOL NEWS FROM 15 TOWNS ATLANTIC LOCALLY OWNED WITH AN INDEPENDENT VOICE 5 TIMES THE REACH AT LESS THAN HALF THE COMPETITORS’ RATE! NEWS To Advertise Call PRICELESS! MIchelle or Sheri at (603) 926-4557 6/17/06 5 PM 5:30 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 WBZ-4 Intercontinental Pok- News CBS Entertainment CSI: NY “Super Men” 48 Hours Mystery “Written in Blood” ’ News (:35) The (12:05) Da Vinci’s In- (CBS) er Champ. (CC) News Tonight (N) ’ (CC) ’ (HD) (CC) (CC) Insider quest (CC) WCVB-5 Explo- Ebert & News ABC Wld 24 “Day 2: 9:00 - ››› Lady and the Tramp (1955) (HD) Voic- The Evidence “Wine News (:35) Star Trek: En- Home- (ABC) ration Roeper (CC) News 10:00PM” ’ (CC) es of Peggy Lee. ’ (CC) and Die” (N) (CC) terprise “Home” ’ Team (N) WCSH-6 Golf U.S. -

MOBILE SUIT GUNDAM and INTERIORITY By

INSIDE THE BOY INSIDE THE ROBOT: MOBILE SUIT GUNDAM AND INTERIORITY by JOHN D. MOORE A THESIS Presented to the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2017 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: John D. Moore Title: Inside the Boy Inside the Robot: Mobile Suit Gundam and Interiority This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures by: Alisa Freedman Chair Glynne Walley Member and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2017. ii © 2017 John D. Moore iii THESIS ABSTRACT John D. Moore Master of Arts Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures September 2017 Title: Inside the Boy Inside the Robot: Mobile Suit Gundam and Interiority Mobile Suit Gundam (1979-1980) is an iconic series in the genre of television anime featuring giant fighting robots, embedded in a system of conventions developed across decades of media aimed at boys that emphasizes action and combat. In this thesis, I argue that Gundam foregrounds the interiority of its main character Amuro, challenging conventions governing the boy protagonist. Using Peter Verstraten's principles of film narratology and Thomas Lamarre’s theory of limited animation, I find in Gundam's narrative strategies sophisticated techniques developed to portray his inner life. -

Hbo Carryover Movies Noiembrie 2010 Felicia Inainte

HBO CARRYOVER MOVIES NOIEMBRIE 2010 FELICIA INAINTE DE TOATE (AKA. FIRST OF ALL, FELICIA) Dramă, România 2009 Regia: Răzvan Rădulescu, Melissa de Raaf Cu: Ileana Cernat, Ozana Oancea Felicia, înainte de toate este o poveste amară şi, pe alocuri, amuzantă, despre cum 19 ani de lipsă de comunicare, concentraţi într-o singură zi, pot dezbina o familie. Ziua de plecare a Feliciei (după vizita făcută în fiecare an familiei ei din Bucureşti) este, ca întotdeauna, foarte agitată. Felicia începe prea târziu să-şi strângă lucrurile, mama face un mic dejun copios, iar tatăl se teme că nu va mai trăi să-şi vadă fiica din nou. În plus, Iulia sună să anunţe că nu mai ajunge la timp să îşi ducă sora la aeroport. În timp ce taxiul îşi face loc prin aglomeraţia din Bucureşti, Felicia şi mama ei se înţeleg că vor pierde avionul. Încercând să îşi reprogrameze zborul, Felicia trebuie să înfrunte cele două familii (fostul soţ şi copilul în Olanda, aşteptând-o să se întoarcă la timp) şi tatăl şi sora, care încearcă amândoi să fie de ajutor în felul lor. Toate acestea şi întreruperea comunicării cu mama ei arată drumul dureros pe care l-a parcurs Felicia în cei 19 ani de stat departe de familia ei. Unul dintre cele mai complexe, mai atent observate şi mai nuanţate portrete feminine din istoria cinema-ului românesc, dar şi un film care vorbeşte de înstrăinarea de ţară şi de familie. GRAN TORINO Dramă, SUA 2008 Regia: Clint Eastwood Walt Kowalski, un veteran al razboiului din Coreea, priveşte cu ochi răuvoitori la lumea în continuă schimbare din jurul sau. -

Počet Uvedenechy SK

prehled nÁVŠTĚVNOST 45 40 35 Number of admissions 30 (millions) Polish films 25 European films US films 20 15 10 5 0 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Návštevnost ČR 20 000 000 16 000 000 12 000 000 diváků celkem 8 000 000 4 000 000 0 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 počet uvedených titulů PL Počet uvedenechy SK 350 250 300 200 250 Polish films European films 200 US films 150 premiér 150 ostatní 100 StránkaNumber 1 of films 100 released 50 50 0 0 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 počet uvedených titulů PL Počet uvedenechy SK 350 250 300 200 250 Polish films European films 200 prehled US films 150 premiér 150 ostatní Number of films 100 100 released 50 50 0 0 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Stránka 2 prehled Návštěvnost SK 12 10 8 Madagaskar 6 4 2 0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 Návštevnost ČR 20 000 000 16 000 000 12 000 000 diváků celkem 8 000 000 4 000 000 0 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Premiér ČR Počet uvedenechy SK 400 250 350 200 300 250 150 premiér 200 100 150 Stránka 3 50 100 0 50 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 0 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 Premiér ČR Počet uvedenechy SK 400 250 350 200 300 250 prehled 150 premiér 200 100 150 50 100 0 50 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 0 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 -

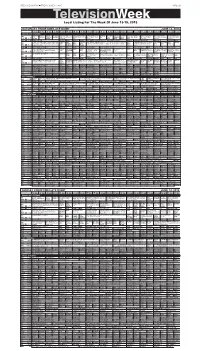

Televisionweek Local Listing for the Week of June 13-19, 2015

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, JUNE 12, 2015 PAGE 7B TelevisionWeek Local Listing For The Week Of June 13-19, 2015 SATURDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT JUNE 13, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS America’s Victory Prairie America’s Classic Gospel The The Lawrence Welk Father Brown “The Keeping As Time Last of The Red No Cover, No Mini- Austin City Limits Front and Center Globe Trekker Anti- PBS Test Garden’s Yard and Heartlnd Gaither Vocal Band. (In Show A tribute to New Eye of Apollo” (In Ste- Up Goes Summer Green mum “Doyle Bram- Nine Inch Nails per- “Here Come the Mum- Communist sculptures. KUSD ^ 8 ^ Kitchen Garden Stereo) Å York. reo) Å By Å Wine Show hall II” forms. Å mies” Å Å (DVS) KTIV $ 4 $ LPGA Tour Golf Cars.TV News News 4 Insider 2015 Stanley Cup Final: Game 5 -- Blackhawks at Lightning News 4 Saturday Night Live Å Extra (N) Å 1st Look House LPGA Tour Golf KPMG LPGA Championship, Paid Pro- NBC KDLT The Big 2015 Stanley Cup Final Game 5 -- Chicago Blackhawks at Tampa Bay KDLT Saturday Night Live Host Martin The Simp- The Simp- KDLT (Off Air) NBC Third Round. From Westchester Country Club gram Nightly News Bang Lightning. From Amalie Arena in Tampa, Fla. (N) (In Stereo Live) Å News Freeman; Charli XCX. -

A1, A2 4-5-05 Front Section

www.tooeletranscript.com TUESDAY TOOELETRANSCRIPT Cowboys, Buffs reach for region baseball victories. See A10 BULLETIN April 5, 2005 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 111 NO. 90 50 cents Planned landfill worries ranchers by Karen Lee Scott STAFF WRITER Ranchers and nearby neigh- bors expressed their concerns last night about some grazing grounds being transformed into a large landfill near US Magnesium. photography / Mike Call At a public hearing hosted A photo of Pope John Paul II was placed on a table to greet members of St. by the Tooele County Health Marguerite’s Parish who gathered Saturday to celebrate the life of the Holy Father, who died earlier that day. The Mass was led by Father Matthew Department, the future of Wixted (shown in the other photo) after celebrating Easter Communion with some 3,200 acres of School and the pope in 1992. Father Wixted was also invited into one of the Vatican’s Institutional Trust Lands was dis- private chapels for a one-on-one visit with the beloved pontiff. cussed. Most of that property is cur- rently being used by a number of different ranchers for cattle graz- ing purposes. But if all goes well Tooele parish for Allied Waste/BFI, some 460 acres in the same area will soon be fenced off to become part of a Class 5 landfill. Dirt from other mourns passing portions of the property will be used to backfill completed waste cells. Only 50 acres of the fenced of adored pope area will be used at first and Darin Olson, environmental man- St. -

Retro: Eastern Illinois Sat, Nov 30, 1963

Retro: Eastern Illinois Sat, Nov 30, 1963 North vs South, part 2 from TV Guide-Eastern Illnois edition WCIA 3-Champaign/WMBD 31-Peoria/W71AE LaSalle-Peru (CBS; 71 relays 31) 6:30 Sunrise Semester "Outlines of Art" 7:00 Captain Kangaroo 8:00 Alvin 8:30 Tennessee Tuxedo 9:00 Quick Draw McGraw 9:30 Mighty Mouse 10:00 Rin Tin Tin 10:30 Roy Rogers 11:00 Sky King 11:30 (3) History Telecourse "New Dealism: Second Phase" 11:30 (31) CBS News 11:45 (31) Army-Navy Game Preview noon College Football: Army-Navy Game 3:00 Football Scoreboard 3:15 CBS All-America Team 3:45 (3) Cartoon Carnival 3:45 (31) Air Force Story 4:00 (3) I Search for Adventure 4:00 (31) Film Feature "South of Germany" 4:30 (3) What Do You Say? 5:00 Hop 6:00 News/Weather/Sports 6:30 Jackie Gleason 7:30 Defenders 8:30 Phil Silvers 9:00 Gunsmoke 10:00 (3) Wanted-Dead or Alive 10:00 (31) News 10:30 (3) News/Weather/Sports 10:30 (31) Movie "The Invisible Man's Revenge" 11:00 (3) Movie "The Detective" 11:55 (31) Movie "Chinatown Squad" WTVP 17-Decatur/WTVH 19-Peoria/W70AF Champaign-Urbana (ABC; 70 relays 17) 9:00 (19) My Friend Flicka 9:30 Jetsons 10:00 Casper 10:30 Beany & Cecil 11:00 Bugs Bunny 11:30 Allakazam noon (17) My Friend Flicka noon (19) Farm Report 12:30 American Bandstand (guests Chubby Checker and Donald Jenkins) 1:30 (17) Bourbon Street Beat 1:30 (19) Bids from the Kids 2:30 (17) Texan 2:30 (19) Sea Hunt 3:00 Wide World of Sports: Grey Cup '63: Hamilton 21-BC 10 6:00 Laughs for Sale 6:30 Hootenanny (from Pittsburgh: guests the Tarriers, Josh White, the Brothers Four, Ian & Sylvia (Tyson), Will Holt, Elan Stuart, John Carignon, and Woody Allen) 7:30 Lawrence Welk 8:30 Jerry Lewis (guests Pearl Bailey, Phil Foster, Peter Nero, Jack Jones, and Lucho Navarro) 10:30 Untouchables 11:30 (17) Roaring 20s 11:30 (19) Rebel mid. -

Fort Myers Attorney

OUTDOORS — 17A I BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID SANIBEL,FL. PERMIT #33 t 'u POSTAL PATRON Vol. 37, Wo. 24 Friday, June 1 9, 1998 Two Sections, 48 pages 75 Cents 1 WASTE PLANS Sanibel City Council decides on $ 15 million plan to treat waste- water on-island. Seepage 3A FATHER'S DAY Kristie Seaman writes about a few underappreciated fathers ...Seepage 3A TOP FISHING Rob Wefls wins the Caloosa Catch & Release Fishing Tourna- ment -^perhaps the largest flats fishing tournament in Florida. ........See page 3A ISLAND SCENE • Island Night • Chamber After Hours Seepage9'llA OUTDOORS • Building nesting boxes • Beachview Golf»Course wins restoration award • How to prepare your boat for a hurricane. See page 17A Arts 7B Business Services ... 20B Classifieds....... 20-23A Crossword 22B Police Beat 7A Night Life............... 3B Jim Fowler's bobcat photo is just one of the excellent photos in the 1999 Sanibel-Captiva Natire Calendar that was published this month. This bobcat "kitten " was photographed in the Bailey Tract last year. See page 3A for another photograph of a bobcat • this one shot this spring as it heads for a picnic dinner. L 2A • Friday, JUNE 19,1998 - ISLANDER 0 V..-*-* Peggy Jim Branyon Saundra Jack Wendy Carmel Ken Frey Tom Andy Sandy Dave David McLaughlin Dorothy Sherrill Karen Gelberg Koch Eaton Linda McLaughlin sprouse Sims Bell Miller GG Mealy Samler Humphrey Casale <Claudia Wiley An le La Frey Margie Janie " Marsh•'---•-a- John George Robideau 8 P' Ellie Fred Mueller George Clifford charlie g Elisabeth Davison Pritchard Bates Kohlbrenner Lorj Tony Lapi ee Veillette Loretta Geiger Smith Susan Rosica Mary Lou Bailey McGowen John Smith PUNTA RASSA Perfect location; close to Sanibel, great water views.