CONCEPTS for LATIN SYNTAX Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Noun Group and Verb Group Identification for Hindi

Noun Group and Verb Group Identification for Hindi Smriti Singh1, Om P. Damani2, Vaijayanthi M. Sarma2 (1) Insideview Technologies (India) Pvt. Ltd., Hyderabad (2) Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Mumbai, India [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT We present algorithms for identifying Hindi Noun Groups and Verb Groups in a given text by using morphotactical constraints and sequencing that apply to the constituents of these groups. We provide a detailed repertoire of the grammatical categories and their markers and an account of their arrangement. The main motivation behind this work on word group identification is to improve the Hindi POS Tagger’s performance by including strictly contextual rules. Our experiments show that the introduction of group identification rules results in improved accuracy of the tagger and in the resolution of several POS ambiguities. The analysis and implementation methods discussed here can be applied straightforwardly to other Indian languages. The linguistic features exploited here are drawn from a range of well-understood grammatical features and are not peculiar to Hindi alone. KEYWORDS : POS tagging, chunking, noun group, verb group. Proceedings of COLING 2012: Technical Papers, pages 2491–2506, COLING 2012, Mumbai, December 2012. 2491 1 Introduction Chunking (local word grouping) is often employed to reduce the computational effort at the level of parsing by assigning partial structure to a sentence. A typical chunk, as defined by Abney (1994:257) consists of a single content word surrounded by a constellation of function words, matching a fixed template. Chunks, in computational terms are considered the truncated versions of typical phrase-structure grammar phrases that do not include arguments or adjuncts (Grover and Tobin 2006). -

C:\#1 Work\Greek\Wwgreek\REVISED

Review Book for Luschnig, An Introduction to Ancient Greek Part Two: Lessons VII- XIV Revised, August 2007 © C. A. E. Luschnig 2007 Permission is granted to print and copy for personal/classroom use Contents Lesson VII: Participles 1 Lesson VIII: Pronouns, Perfect Active 6 Review of Pronouns 8 Lesson IX: Pronouns 11 Perfect Middle-Passive 13 Lesson X: Comparison, Aorist Passive 16 Review of Tenses and Voices 19 Lesson XI: Contract Verbs 21 Lesson XII: -MI Verbs 24 Work sheet on -:4 verbs 26 Lesson XII: Subjunctive & Optative 28 Review of Conditions 31 Lesson XIV imperatives, etc. 34 Principal Parts 35 Review 41 Protagoras selections 43 Lesson VII Participles Present Active and Middle-Passive, Future and Aorist, Active and Middle A. Summary 1. Definition: A participle shares two parts of speech. It is a verbal adjective. As an adjective it has gender, number, and case. As a verb it has tense and voice, and may take an object (in whatever case the verb takes). 2. Uses: In general there are three uses: attributive, circumstantial, and supplementary. Attributive: with the article, the participle is used as a noun or adjective. Examples: @Ê §P@<JgH, J Ð<J", Ò :X88T< PD`<@H. Circumstantial: without the article, but in agreement with a noun or pronoun (expressed or implied), whether a subject or an object in the sentence. This is an adjectival use. The circumstantial participle expresses: TIME: (when, after, while) [:", "ÛJ\6", :gJ">b] CAUSE: (since) [Jg, ñH] MANNER: (in, by) CONDITION: (if) [if the condition is negative with :Z] CONCESSION: (although) [6"\, 6"\BgD] PURPOSE: (to, in order to) future participle [ñH] GENITIVE ABSOLUTE: a noun / pronoun + a participle in the genitive form a clause which gives the circumstances of the action in the main sentence. -

The Teaching of Grammar in Arabic Countries a Case Study of the Teaching of the Difference Between Nominal and Verbal Sentences at High Schools in Rabat

Josien Boetje The teaching of grammar in Arabic countries A case study of the teaching of the difference between nominal and verbal sentences at high schools in Rabat Bachelor’s thesis Supervisors: Dr. C.H.M.Versteegh, Drs. C.A.E.M. Hanssen Date: 04-07-2011 Faculty of Humanities, Universiteit Utrecht Table of contents 1. Introduction 2. The theory of sentence type in traditional Arabic grammar 2.1 The nominal sentence 2.2 The verbal sentence 2.3 The distinction between the nominal and the verbal sentence 2.3.1’ibtidā’ 2.3.2 ’isnād 3. The explanation of sentence types in the Moroccan educational system 3.1 Morocco and its language policy 3.1.1 Moroccan linguistic background 3.1.2 Languages in the educational system 3.2 The explanation of sentence types in the Moroccan educational system 3.2.1. The nominal sentence 3.2.2 The verbal sentence 4. Comparison between the Classical and the modern approach 5. Theory and practice 5.1 Analysis of the respondents 5.2 Results 6. Conclusion 2 1. Introduction The Arabic grammatical tradition is a long tradition that flourished between 800 and 1500 C.E. approximately. It is usually said to have started with Sībawayh, a Persian scholar who lived in the 8th century C.E. He was the first non-Arab who wrote on Arabic grammar and is famous for his book Kitāb Sībawayh ‘The Book of Sībawayh’, which is the first written treatise of Arabic grammar in a systematic fashion. He was mainly focused on the formal and syntactic aspects of the Arabic language. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Towards Licensing of Adverbial Noun Phrases in HPSG

Towards Licensing of Adverbial Noun Phrases in HPSG Beata Trawinski University of Tubingen¨ Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar Center for Computational Linguistics, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven Stefan Muller¨ (Editor) 2004 CSLI Publications pages 294–312 http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/HPSG/2004 Trawinski, Beata. 2004. Towards Licensing of Adverbial Noun Phrases in HPSG. In Muller,¨ Stefan (Ed.), Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Head- Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, Center for Computational Linguistics, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 294–312. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications. Abstract This paper focuses on aspects of the licensing of adverbial noun phrases (AdvNPs) in the HPSG grammar framework. In the first part, empirical is- sues will be discussed. A number of AdvNPs will be examined with respect to various linguistic phenomena in order to find out to what extent AdvNPs share syntactic and semantic properties with non-adverbial NPs. Based on empirical generalizations, a lexical constraint for licensing both AdvNPs and non-adverbial NPs will be provided. Further on, problems of structural li- censing of phrases containing AdvNPs that arise within the standard HPSG framework of Pollard and Sag (1994) will be pointed out, and a possible solution will be proposed. The objective is to provide a constraint-based treatment of NPs which describes non-redundantly both their adverbial and non-adverbial usages. The analysis proposed in this paper applies lexical and phrasal implicational constraints and does not require any radical mod- ifications or extensions of the standard HPSG geometry of Pollard and Sag (1994). Since adverbial NPs have particularly high frequency and a wide spec- trum of uses in inflectional languages such as Polish, we will take Polish data into consideration. -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

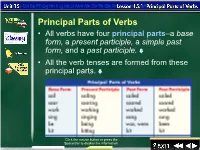

Principal Parts of Verbs • All Verbs Have Four Principal Parts–A Base Form, a Present Participle, a Simple Past Form, and a Past Participle

Principal Parts of Verbs • All verbs have four principal parts–a base form, a present participle, a simple past form, and a past participle. • All the verb tenses are formed from these principal parts. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 1 Lesson 1-2 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) • You can use the base form (except the base form of be) and the past form alone as main verbs. • The present participle and the past participle, however, must always be used with one or more auxiliary verbs to function as the simple predicate. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 2 Lesson 1-3 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) – Carpenters work. [base or present form] – Carpenters worked. [past form] – Carpenters are working. [present participle with the auxiliary verb are] – Carpenters have worked. [past participle with the auxiliary verb have] Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 3 Lesson 1-4 Exercise 1 Using Principal Parts of Verbs Complete each of the following sentences with the principal part of the verb that is indicated in parentheses. 1. Most plumbers _________repair hot water heaters. (base form of repair) 2. Our plumber is _________repairing the kitchen sink. (present participle of repair) 3. Last month, he _________repaired the dishwasher. (past form of repair) 4. He has _________repaired many appliances in this house. (past participle of repair) 5. He is _________enjoying his work. (present participle of enjoy) Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the answers. -

Letters to the Editor

Journal of Translation, Volume 1, Number 3 (2005) Letters to the Editor Response to “Logical Subjects, Grammatical Subjects, and the Translation of Greek Person and Number Agreement” Ettien Koffi’s article [1] in the last issue of this journal is successful in highlighting the need for translators to give proper consideration to the interaction of syntax with semantics and pragmatics, particularly in the seemingly straightforward area of subject-verb agreement. I appreciate Koffi for directing our attention to three significant texts—Galatians 1:8, 2 Thessalonians 2:16, and Colossians 2:1–2—that are syntactically difficult. As Koffi argues, a translation dilemma arises when the verb does not agree in person and/or number with each noun phrase (NP) of a conjoined subject, i.e., NP + NP.[2] Language specific resolution rules[3] determine the form of agreement between the verb and such a compound subject, but the receptor language may follow a different pattern than the source language. Thus, I wholeheartedly agree with Koffi’s main thesis, that “the failure to clearly identify the controller of agreement in Greek has led to translations that are exegetically and theologically questionable.”[4] The translator must understand the rules of grammatical concord in both the source language and the receptor language. If the resolution rules differ between the two languages, the translator must be cautious lest a literal translation gives the wrong meaning. Koffi’s examples from English, French, and West African translations make us well aware of the potential problems. However, Koffi follows the introductory Greek grammar of Gerald L. -

Bilingual Complex Verbs: So What’S New About Them? Author(S): Tridha Chatterjee Proceedings of the 38Th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (2014), Pp

Bilingual Complex Verbs: So what’s new about them? Author(s): Tridha Chatterjee Proceedings of the 38th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (2014), pp. 47-62 General Session and Thematic Session on Language Contact Editors: Kayla Carpenter, Oana David, Florian Lionnet, Christine Sheil, Tammy Stark, Vivian Wauters Please contact BLS regarding any further use of this work. BLS retains copyright for both print and screen forms of the publication. BLS may be contacted via http://linguistics.berkeley.edu/bls/ . The Annual Proceedings of the Berkeley Linguistics Society is published online via eLanguage , the Linguistic Society of America's digital publishing platform. Bilingual Complex Verbs: So what’s new about them?1 TRIDHA CHATTERJEE University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Introduction In this paper I describe bilingual complex verb constructions in Bengali-English bilingual speech. Bilingual complex verbs have been shown to consist of two parts, the first element being either a verbal or nominal element from the non- native language of the bilingual speaker and the second element being a helping verb or dummy verb from the native language of the bilingual speaker. The verbal or nominal element from the non-native language provides semantics to the construction and the helping verb of the native language bears inflections of tense, person, number, aspect (Romaine 1986, Muysken 2000, Backus 1996, Annamalai 1971, 1989). I describe a type of Bengali-English bilingual complex verb which is different from the bilingual complex verbs that have been shown to occur in other codeswitched Indian varieties. I show that besides having a two-word complex verb, as has been shown in the literature so far, bilingual complex verbs of Bengali-English also have a three-part construction where the third element is a verb that adds to the meaning of these constructions and affects their aktionsart (aspectual properties). -

Caesar's De Bello Gallico I

Caesar's De Bello Gallico I Latin Text with Facing Vocabulary and Commentary Geoffrey Steadman Beta Edition April 2013 Caesar's De Bello Gallico I Latin Text with Facing Vocabulary and Commentary Beta Edition © 2013 by Geoffrey D. Steadman All rights reserved. Subject to the exception immediately following, this book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. The author has made an online version of this work available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License. The terms of the license can be accessed at creativecommons.org. Accordingly, you are free to copy, alter, and distribute this work under the following conditions: (1) You must attribute the work to the author (but not in any way that suggests that the author endorses your alterations to the work). (2) You may not use this work for commercial purposes. (3) If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license as this one. ISBN-13: ISBN-10: Published by Geoffrey Steadman Cover Design: David Steadman Fonts: Times New Roman [email protected] xii xiii The Life of Julius Caesar How to Use this Commentary Research shows that, as we learn how to read in a second language, a combination of reading and B.C. direct vocabulary instruction is statistically superior to reading alone. -

Features, Syntax, and Categories in the Latin Perfect Davidembick

Features, Syntax, and Categories in the Latin Perfect DavidEmbick Theanalysis centers on thenotion of category in synthetic and analytic verbalforms and on thestatus of thefeature that determines the forms ofthe Latin perfect. In this part of the Latin verbal system, active formsare synthetic (‘ ‘verbs’’) butpassive forms are analytic (i.e., participleand finite auxiliary). I showthat the two perfects occur in essentiallythe same structure and are distinguished by adifferencein movementto T; moreover,the difference in forms can be derived withoutreference to category labels like ‘ ‘Verb’’ or‘ ‘Adjective’’ on theRoot. In addition, the difference in perfects is determined by a featurewith clear syntactic consequences, which must be associated arbitrarilywith certain Roots, the deponentverbs.I discussthe implica- tionsof these points in the context of Distributed Morphology, the theoryin whichthe analysis is framed. Keywords: syntax/morphologyinterface, category, features, passive voice,Distributed Morphology 1Introduction Questionssurrounding the relationship between syntactic and morphological definitions of cate- goryhave played and continue to play an importantrole in grammatical theory. Similarly, issues concerningthe type, nature, and distribution of features in different modules of the grammar definea numberof questions in linguistic theory. In this article I examinethe syntactic and morphologicalprocesses and features at playin theconstruction of analyticand synthetic verbal forms, andin the determination of differentsurface categories. I focusprimarily on thefact that theLatin perfect is syntheticin the active voice (e.g., ama¯v¯õ ‘I(have)loved’ ) butanalytic in the passive,with a participialform ofthemain verb and a form oftheauxiliary ‘ be’( ama¯tus sum). Theoretically,the analysis addresses (a) thestatus of category in syntax and morphology, and (b) thestatus of thefeature underlying the analytic /syntheticdifference. -

Greek Grammar Review

Greek Study Guide Some Step-by-Step Translation Issues I. Part of Speech: Identify a word’s part of speech (noun, pronoun, adjective, verb, adverb, preposition, conjunction, particle, other) and basic dictionary form. II. Dealing with Nouns and Related Forms (Pronouns, Adjectives, Definite Article, Participles1) A. Decline the Noun or Related Form 1. Gender: Masculine, Feminine, or Neuter 2. Number: Singular or Plural 3. Case: Nominative, Genitive, Dative, Accusative, or Vocative B. Determine the Use of the Case for Nouns, Pronouns, or Substantives. (Part of examining larger syntactical unit of sentence or clause) C. Identify the antecedent of Pronouns and the referent of Adjectives and Participles. 1. Pronouns will agree with their antecedent in gender and number, but not necessarily case. 2. Adjectives/participles will agree with their referent in gender, number, and case (but will not necessary have the same endings). III. Dealing with Verbs (to include Infinitives and Participles) A. Parse the Verb 1. Tense/Aspect: Primary tenses: Present, Future, Perfect Secondary (past time) tenses: Imperfect, Aorist, Pluperfect 2. Mood: Moods: Indicative, Subjunctive, Imperative, or Optative Verbals: Infinitive or Participle [not technically moods] 3. Voice: Active, Middle, or Passive 4. Person: 1, 2, or 3. 5. Number: Singular or Plural Note: Infinitives do not have Person or Number; Participles do not have Person, but instead have Gender and Case (as do nouns and adjectives). B. Review uses of Infinitives, Participles, Subjunctives, Imperatives, and Optatives before translating these. C. Review aspect before translating any verb form. · See p. 60 in FGG (3rd and 4th editions) to translate imperfects and all present forms.