Teaching Interfaith Relations at Universities in the Arab Middle East: Challenges and Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Representing the Algerian Civil War: Literature, History, and the State

Representing the Algerian Civil War: Literature, History, and the State By Neil Grant Landers A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in French in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Debarati Sanyal, Co-Chair Professor Soraya Tlatli, Co-Chair Professor Karl Britto Professor Stefania Pandolfo Fall 2013 1 Abstract of the Dissertation Representing the Algerian Civil War: Literature, History, and the State by Neil Grant Landers Doctor of Philosophy in French Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Debarati Sanyal, Co-Chair Professor Soraya Tlatli, Co-Chair Representing the Algerian Civil War: Literature, History, and the State addresses the way the Algerian civil war has been portrayed in 1990s novelistic literature. In the words of one literary critic, "The Algerian war has been, in a sense, one big murder mystery."1 This may be true, but literary accounts portray the "mystery" of the civil war—and propose to solve it—in sharply divergent ways. The primary aim of this study is to examine how three of the most celebrated 1990s novels depict—organize, analyze, interpret, and "solve"—the civil war. I analyze and interpret these novels—by Assia Djebar, Yasmina Khadra, and Boualem Sansal—through a deep contextualization, both in terms of Algerian history and in the novels' contemporary setting. This is particularly important in this case, since the civil war is so contested, and is poorly understood. Using the novels' thematic content as a cue for deeper understanding, I engage through them and with them a number of elements crucial to understanding the civil war: Algeria's troubled nationalist legacy; its stagnant one-party regime; a fear, distrust, and poor understanding of the Islamist movement and the insurgency that erupted in 1992; and the unending, horrifically bloody violence that piled on throughout the 1990s. -

To View Online Click Here

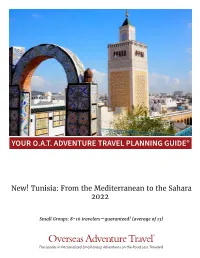

YOUR O.A.T. ADVENTURE TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE® New! Tunisia: From the Mediterranean to the Sahara 2022 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 13) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Personalized Small Group Adventures on the Road Less Traveled 1 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. And the O.A.T. New! Tunisia: From the Mediterranean to the Sahara itinerary you’ve expressed interest in will be a wonderful way to resume the discoveries that bring us so much joy. You might soon be enjoying standout moments like these: Venture out to the Tataouine villages of Chenini and Ksar Hedada. In Chenini, your small group will interact with locals and explore the series of rock and mud-brick houses that are seemingly etched into the honey-hued hills. After sitting down for lunch in a local restaurant, you’ll experience Ksar Hedada, where you’ll continue your people-to-people discoveries as you visit a local market and meet local residents. You’ll also meet with a local activist at a coffee shop in Tunis’ main medina to discuss social issues facing their community. You’ll get a personal perspective on these issues that only a local can offer. The way we see it, you’ve come a long way to experience the true culture—not some fairytale version of it. So we keep our groups small, with only 8-16 travelers (average 13) to ensure that your encounters with local people are as intimate and authentic as possible. -

Algeria Cultural Discovery

Algeria Cultural Discovery 9 Days Algeria Cultural Discovery Take the road less traveled on this incredible adventure in Algeria — one of the least visited countries in the world! Experience the rare beauty of cosmopolitan Algiers, with its historic Casbah and labyrinthine old quarter. Then explore the impressive and well-preserved Roman ruins at Tipasa, beautifully situated on the Mediterranean, and Timgad. Travel deep into the heart of the M'Zab Valley and explore its enchanting fortress cities rising from the dunes. With deep history and ancient UNESCO-listed relics at every step, you'll find yourself in a fascinating land wondering why it wasn't on your radar sooner. Details Testimonials Arrive: Algiers, Algeria “We have traveled throughout the world, but never experienced a level of service and attention to detail Depart: Algiers, Algeria as we did with MT Sobek.“ Dennis G. Duration: 9 Days Group Size: 4-12 Guests “I have taken 12 trips with MT Sobek. Each has left a positive imprint on me—widening my view of the Minimum Age: 14 Years Old world and its peoples.” Jane B. Activity Level: . REASON #01 REASON #02 REASON #03 MT Sobek captures the best Our team of local guides This 9-day adventure has been of Algeria on this unique and are true experts and have crafted to pair effortlessly with immersive insider adventure decades of experience leading a 6-day extension to help you spanning the country's guests through Algeria. maximize your time in Algeria. historical and cultural wonders. ACTIVITIES LODGING CLIMATE In-depth cultural touring, including Luxurious 4- and 5-star hotels Algeria's coastal areas have a exploring five UNESCO World with elegant rooms and typical Mediterranean climate Heritage wonders and enjoying scenic locations - all carefully with warm, dry summers authentic local encounters. -

Du Ceri Centre D'études Et De Recherches

les études du Ceri Centre d’Études et de Recherches Internationales Algeria: The Illusion of Oil Wealth Luis Martinez Algeria: The Illusion of Oil Wealth Abstract Thirty years after the nationalization of hydrocarbons Algeria’s oil wealth seems to have disappeared judging by its absence in the country’s indicators of well-being. In Algeria, oil brought happiness to a few and misery for many. The lack of oversight over oil revenue led to the industries downfall. Since 2002, oil wealth has returned to Algeria. The per-barrel price increase from $30 to $147 between 2002 and 2008 provided the country with unexpected revenue enabling it to accumulate an estimated $150 billion in dollar reserves, in 2009. Abdelaziz Bouteflika, who returned to a devastated Algeria to restore civil order, unexpectedly benefited from this price increase. Thus, he was able to offer Algeria not only national reconciliation but also renewed economic growth. However, given that the wounds of the 1990s are not entirely healed and the illusions of oil wealth have evaporated with the randomness of economic instability, this unexpected return of financial abundance raises concerns. To what ends will this windfall be put? Who will control it? Will it provoke or sustain a renewal of violence and conflict? Les illusions de la richesse pétrolière Résumé Trente ans après la nationalisation des hydrocarbures, la richesse pétrolière accumulée semble disparue tant elle est absente des indicateurs d’évaluation du bien être. En Algérie, elle a fait le bonheur d’une minorité et la tristesse de la majorité. L’absence de contrôle exercé sur la rente pétrolière a conduit à sa dilapidation. -

Curriculum Vitae Dr

Curriculum Vitae Dr. Nadjib Benkheira Department of Islamic History and Civilization University of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates 2017 Place of Birth: Bou Saâda, Algeria Academic Qualifications: Fine Field of Specialization: History of the Abbasid Period (132 Hijri – 656 Hijri) Major Field of Specialization: Islamic History / Islamic Civilization 2004: Ph.D., History and Islamic Civilization with Honors, and commendation by the discussion committee, Islamic History Department, Emir Abdelkader University of Islamic Sciences, University of Constantine, Algeria 1995: Master’s in Islamic History and Civilization with Honors, Islamic History Department, Emir Abdelkader University of Islamic Sciences, University of Constantine, Algeria 1990: Bachelor of Arts in Islamic History, Islamic Civilization Institute, Emir Abdelkader University of Islamic Sciences, University of Constantine, Algeria (1st in the cohort) Rank: Associate Professor in Islamic History and Civilization, University of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates Research Interests: - Islamic History (1 Hijri – 656 Hijri) - Civil History - History of Sciences in Islamic Civilization - Contemporary Islamic Thought - 1 Membership of Professional Bodies: Member of Arab Historians’ Association Member of Algerian Historians’ Association Member of Algerian Writers’ Association Member of the Scientific Council of the Center for Research in Islamic Sciences and Civilization, Algeria Administrative Responsibilities: - Head of Department of Islamic History and Civilization, University of Sharjah, September 2016 to present - Academic Vice Assistant to the Assistant of the Chancellor for Branches’ Affairs, February 2013 to February 2016 - Coordinator for the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, Khor Fakkan Branch, University of Sharjah, December 2009 to 2013 - Secretary for Council of Scientific Branches, Khor Fakkan, University of Sharjah, 2008 to 2009 Published Books: 1. -

1 LESSONS from an ARAB by John Kiser Introduction I Owe My Interest

LESSONS FROM AN ARAB ( Abdelkader’s Legacy of Empathy and Obedience, 1808-1883) by John Kiser Introduction I owe my interest in Emir Abdelkader to a community of French Trappist monks living in the Atlas Mountains, south of Algiers. The story of their kidnapping in 1996 and eventual death became the subject of a book, The Monks of Tibhirine : Faith, Love and Terror in Algeria. Seven years later, an award- winning French film, Of Men and Gods, was produced based in large measure on the book. Brought to the more God-fearing United States by Sony Classics, it became Of Gods and Men. By a coincidence of history, their monastery of Notre Dame of the Atlas was located below a cliff face called Abdelkader Rock. Curious about the name, I learned from the monks that Abdelkader had once directed a battle against the French from the top of the cliff and is considered by Algerians to be their version of George Washington. Abdelkader was the first Arab leader to unify tribes, however briefly, into a proto-Arab state to resist a French occupation that began with the sack of Algiers in 1830. As it turned out, the emir’s struggle was but the first phase of a “long war” for independence and dignity that lasted until 1962. As I read more about him, I also noted his resemblance to other Americans--- Robert E. Lee and John Winthrop. Like Lee, he was deeply religious, gracious, unwilling to prolong senseless suffering and in defeat, promoted reconciliation. Like Winthrop, Abdelkader believed that good governance required submission to Divine Law: God’s wisdom as revealed through the prophets in the Torah, the Psalms, the Gospels and the Koran— interpreted through the actions and sayings of the Prophet Mohammad, known as the Sunna. -

Regulations 1996

REGULATIONS 1996 REGULATION 96-01 OF MAY 13TH, 1996 RELATING TO THE ISSUE AND PUTTING INTO CIRCULATION OF A BANKNOTE OF (500) FIVE HUNDRED ALGERIAN DINARS The Governor of the Bank of Algeria, Whereas Law 90-10 of April 14th, 1990 relating to Money and Credit, namely to the provisions of its book I, and its Articles 44, Paragraph a, 47 and 107; Whereas the Presidential Decree of July 21st, 1992 relating to the appointment of the Governor of the Bank of Algeria; Whereas the Presidential Decrees of May 14th, 1990 relating to the appointments of the Vice-Governors of the Bank of Algeria; Whereas the Executive Decree of July 1st, 1991 designating the Regular Members of the Council of Money and Credit and their substitutes; Whereas Regulation 92-06 of May 21st, 1992 relating to the creation of a series of banknotes with an Algerian dinar value of (1000) one thousand, (500) five hundred, (200) two hundred, (100) one hundred and (50) fifty Further to the Resolution of the Council of Money and Credit of March 13th, 1996 promulgates the Regulation the content of which follows: Article 1: Under Regulation 92-06 of May 21st, 1992 relating to the creation of a series of banknotes with an Algerian dinar value of (1000) one thousand, (500) five hundred, (200) two hundred, (100) one hundred and (50) fifty, the Bank of Algeria has issued a banknote with an Algerian dinars value of (500) five hundred. This new banknote shall be put into circulation further to the promulgation of this Regulation. Article 2: The special peculiarities, namely, the detailed specifications of this banknote shall be outlined as follows: 1. -

423 – Aquatic Hemiptera of Northeastern

AQUATIC HEMIPTERA OF NORTHEASTERN ALGERIA: DISTRIBUTION, PHENOLOGY AND CONSERVATION Fouzi ANNANI 1,2, Ahmed H. AL F ARHAN 3 & Boudjéma SA M RAOUI 1,3* RÉSUMÉ.— Hémiptères aquatiques du nord-est de l’Algérie : distribution, phénologie et conserva- tion.— L’échantillonnage de 83 sites à travers le complexe de zones humides du nord-est Algérien, un point chaud de la biodiversité aquatique, a permis d’identifier 35 espèces d’hémiptères aquatiques. La répartition et la phénologie des espèces sont présentées et les histoires de vie de Notonecta glauca et Notonecta obli- qua déduites. Ces deux espèces estivent dans des milieux refuges à hautes altitudes avant de redescendre se reproduire en plaine à l’automne. Diverses manifestations de changements globaux (pompage de l’eau, construction de barrages, introduction d’espèces exotiques et fragmentation des milieux) influencent néga- tivement l’intégrité écologique des milieux de la région étudiée. SUMMARY.— A survey, involving the sampling of 83 sites, investigated the aquatic hemiptera of north- eastern Algeria, a well known hotspot of aquatic biodiversity. The study recorded 35 species with data on distribution and phenology presented and discussed. Aspects of the life history of some species (Notonecta glauca and Notonecta obliqua) were inferred from their distribution and phenology and they were found to aestivate at high altitude refuges. Insect conservation in North Africa is still embryonic, relying mainly on protected areas to provide surrogate conservation to a rich and diverse group. This is inadequate in view of the current distribution of aquatic insects, often located in unprotected habitats (intermittent streams, temporary pools, dunary ponds) and the fact that diverse manifestations of global changes (loss of habitats due to water extraction and dam construction, invasive species, habitat fragmentation) are fast eroding the biodiversity of protected areas. -

Mutual Othering

Chapter 1 Literary Depictions of the Moor, Travel Writing, and the Maghreb Many critics have explored the implications of cross-cultural contact on the confi gurations of self and alterity in travel writing in rela- tion to colonized areas such as the Middle East, India, Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America.1 However, despite the rich persistence of depictions of North Africans/Moors in literature from the Middle Ages to the present, there has been little analysis of their appearance in European travel literature of the nineteenth century. Similarly, primary texts by North Africans that also document cross-cultural encounters between North Africa and Western Europe, written in Arabic, have been neglected by both Arab and Western scholars. More often, this part of the Muslim and Arab African world has been assimilated into studies focusing on works from Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, or the Middle East in general without regard to regional, historical, and political specifi cities of the Maghreb region. In this chapter, I discuss how theoretical approaches taken by orientalist scholars, such as Edward Said and Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, have systematically alienated consideration of the Maghreb as both unique and important from discussions of both the place of the Arab-Muslim in the Western imaginary and in relation to devel- oping political and ideological tensions throughout the nineteenth century. The seminal works of these critics, written decades ago, have remained central to contemporary understanding of the nine- teenth century and have helped perpetuate the elision of North Africa into the larger region of the Middle East. I argue that we need to expand current conceptions of the East to include the status of the Maghreb as a liminal space, neither Eastern nor African; such a shift encourages a more nuanced understanding of persistent ideological tensions that continue to haunt modern cultural relations between West and East, between Christianity and Islam. -

NORTH AFRICA Tunisia, Algeria & Mauritania

NORTH AFRICA Tunisia, Algeria & Mauritania September 19 – October 14, 2021 Led by Lecturer, Guide and Historian, Mohamed Halouani Photo Credit; Gary Krosin Few countries on earth match the historical, cultural, and natural splendor of Tunisia. Begin and end in the capital city of Tunis with its won- drous medina (ancient city) and fascinating souqs (markets). Travel onward to ancient Carthage, one of the most important cities in the ancient Roman Empire. Other important historical sites include Dougga, Sousse, Oudna, and Kerkouane, as well as the sacred Islamic site of Kairouan. Algeria is a vast country of breathtaking scenery, well-preserved Roman ruins, pre-historic cave paintings and a strong Berber culture. Your journey will take you from the sweeping shoreline to the majestic mountains, through the huge wilderness of the Sahara Des- ert into the palm-fringed oases. Some of the highlights include the Roman ruins of Timgad, the former Roman port of Caesarea, the oasis town of Bou Saada and the Kasbah of Algiers. This fascinating tour offers the adventurous traveler an alluring blend of art, history, culture and scenery, including the marvelous city of Constantine, the city of gorges and bridges. Mauritania boasts many natural wonders, as well as ancient cities. In the Middle Ages, Mauritania was the seat of the Almoravid movement that spread Islam throughout North Africa. High- lights include two of its four “ksour” (villages) - Chinguetti and Ouadane - located in northern Mauritania. Chinguetti is a medieval Berber trading center, with stark, unadorned buildings that reflect the strict religious beliefs of the Almoravids. Ouadane is an oasis settlement concealed by waves of golden sand dunes and home to an ancient mosque (and UNESCO World Heritage Site). -

People's Democratic Republic of Algeria

PEOPLE'S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ALGERIA Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research University of Tlemcen Faculty of Letters and languages Department of English Dissertation Submitted to the Department of English as Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master in English Language (Literature and Civilization) Presented by: Supervised by: - Mr. Mouade RAMDANE - Dr. Noureddine MOUHADJER Academic Year: 2015/2016 Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank all the people who contributed in some way to the work described in this Thesis. Primarily, I thank my advisor, Dr. Noureddine MOUHADJER, as well as the co supervisor Dr. Abd-el-Kader BENSAFA. I should like, also, to thank the Members of the Jury, Dr. Nawel BENMOSTEFA, Dr.Bassou Abderrrahmen. I would like also to thank all Algerian historians, all enlightened intellectuals who leads, their daily struggles against obscurantism and illusion, and promote the knowledge and rationalism, to go towards lucidity. I am grateful for the rich scientific sources obtained by them that, allowed me to pursue my graduate school studies. I must express my very profound gratitude and support.I would like to acknowledge the Department of Foreign Languages, Section of English. My graduate experience benefitted greatly from the courses I took, and the high quality Seminars that the department organized there. I Abstract This research, investigates the process of the Algerian culture through time, and seeks to give an evaluative review of it. Then this study will go over and will try to dig deeper and deeper, for the underlying causes of our cultural problems, focusing on the historical process of this problem, since Algeria when it was subjected to the ottoman rule and the French colonization until the aftermath of the independence, through an inductive approach. -

1 Emir Abdelkader Al Jazairy—A Healer for Our Times a Talk by John Kiser at the University of Lyon, France Dec 14, 2013 Let Us

Emir Abdelkader al Jazairy—A Healer for Our Times A Talk by John Kiser at the University of Lyon, France Dec 14, 2013 Let us begin with the name, Abdelkader. Servant of God. A challenging name for a man to carry. Nevertheless, Abdelkader came as close as a human might to fulfilling that implied calling. Following his rescue of Christians in Damascus during the pogrom of 1860, Abdelkader received a letter of gratitude from Bishop Pavy in Algiers. The emir wrote in response: “That which we did for the Christians we did to be faithful to Islamic Law, and out of respect for human rights…. The law places greatest importance on compassion and mercy and all that preserves social cohesion.” Abdelkader then ended his letter with an observation whose relevance is obvious today: “Those who belong to the religion of Mohammad have corrupted it, which is why they are now like lost sheep.” Of course, the idea of proposing a religiously devout individual, even someone like Abdelkader, as a national and international role model is anathema to many secularists, and probably not a few Christians. But why? Some of his greatest admirers were Christians: Bishop Dupuch, the Dominican Sisters who looked after his family in prison and many others. He was a friend of Free Masons and Saint Simonians, awarded the Legion of Honor, received gifts from President Lincoln and Pius IX, praised around the world for saving thousands of Christian lives in Damascus. Muslims and Christians, believers and nonbelievers alike honored him. His most valued accolade came from fellow freedom fighter Emir Chamyl who had finally been defeated by the Russians.