Mutual Othering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching Interfaith Relations at Universities in the Arab Middle East: Challenges and Strategies

religions Article Teaching Interfaith Relations at Universities in the Arab Middle East: Challenges and Strategies Josef Meri College of Islamic Studies, Hamad bin Khalifa University, Education City, 34110 Doha, Qatar; [email protected] Abstract: This study explores the present state of teaching Interfaith/Interreligious Relations at universities in the Arab Middle East. First, it considers the definition and various approaches to teaching Interfaith Relations by leading proponents of Interreligious Studies in the West such as Oddbjørn Leirvik and Marianne Moyaert within a theoretical framework that is sensitive to the Arab Middle Eastern context. It explores several key factors in Arab society that have prevented the teaching of Interfaith Relations in universities. The discussion then turns to the unique Dar Al-Kalima University (Palestine) Interreligious Dialogue Inter-Regional Curriculum initiative and its significance for teaching Interfaith Relations in the university. Finally, the study examines the case study method of teaching developed by Diana Eck at Harvard University, which can be adapted to a Middle Eastern context and offers two unique case studies for university teachers. Keywords: interfaith studies; interreligious studies; interfaith dialogue; disruptive education; teach- ing interfaith studies; interfaith relations 1. Introduction Citation: Meri, Josef. 2021. Teaching This study explores a number of fundamental issues in teaching Interfaith Relations Interfaith Relations at Universities in (IR) at universities in the -

Representing the Algerian Civil War: Literature, History, and the State

Representing the Algerian Civil War: Literature, History, and the State By Neil Grant Landers A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in French in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Debarati Sanyal, Co-Chair Professor Soraya Tlatli, Co-Chair Professor Karl Britto Professor Stefania Pandolfo Fall 2013 1 Abstract of the Dissertation Representing the Algerian Civil War: Literature, History, and the State by Neil Grant Landers Doctor of Philosophy in French Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Debarati Sanyal, Co-Chair Professor Soraya Tlatli, Co-Chair Representing the Algerian Civil War: Literature, History, and the State addresses the way the Algerian civil war has been portrayed in 1990s novelistic literature. In the words of one literary critic, "The Algerian war has been, in a sense, one big murder mystery."1 This may be true, but literary accounts portray the "mystery" of the civil war—and propose to solve it—in sharply divergent ways. The primary aim of this study is to examine how three of the most celebrated 1990s novels depict—organize, analyze, interpret, and "solve"—the civil war. I analyze and interpret these novels—by Assia Djebar, Yasmina Khadra, and Boualem Sansal—through a deep contextualization, both in terms of Algerian history and in the novels' contemporary setting. This is particularly important in this case, since the civil war is so contested, and is poorly understood. Using the novels' thematic content as a cue for deeper understanding, I engage through them and with them a number of elements crucial to understanding the civil war: Algeria's troubled nationalist legacy; its stagnant one-party regime; a fear, distrust, and poor understanding of the Islamist movement and the insurgency that erupted in 1992; and the unending, horrifically bloody violence that piled on throughout the 1990s. -

NH Final Thesis

SOCIAL MARKETING AND THE CORRUPTION CONUNDRUM IN MOROCCO: AN EXPLORATORY ANALYSIS N. HAMELIN Ph.D. 2016 i SOCIAL MARKETING AND THE CORRUPTION CONUNDRUM IN MOROCCO: AN EXPLORATORY ANALYSIS NICOLAS HAMELIN A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of East London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February, 2016 ii Abstract The modern world is characterised by socio-economic disruptions, civil unrests, and weakening of many societal institutions, amongst many other challenges to our social fabric. Therefore, scholars are increasingly scouring a wide variety of conceptual prisms to seek explanations and possible solutions to those problems contemporaneously manifesting themselves. The pervading force of corruption, across the globe, remains a major concern among nations, multilateral agencies, such as Transparency International, and more profoundly in major business and public policy discourses. For many developing countries, especially those with weak institutions, high levels of corruption are causatively associated with high levels of poverty, poor economic performance and under-development. Against this background, using the Kingdom of Morocco as a contextual base, this thesis explores the growing incidence of corruption, which has stunted the nation’s positive development, as well as its triggers, antecedents and consequences. Whilst the literature is replete with treatments of corruption across time and space, such treatments have focused on social and macroeconomic underpinnings but largely lack rigorous marketing-framed explorations. Following on from this lacuna, this thesis situates the treatment of corruption in Morocco within the conceptual frame of social marketing — a demonstrably robust platform for analysing societal issues and, indeed, a validated behavioural intervention model. -

36687838.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Oregon Scholars' Bank AVOIDING THE ARAB SPRING? THE POLITICS OF LEGITIMACY IN KING MOHAMMED VI’S MOROCCO by MARGARET J. ABNEY A THESIS Presented to the Department of Political Science and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2013 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Margaret J. Abney Title: Avoiding the Arab Spring? The Politics of Legitimacy in King Mohammed VI’s Morocco This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of Political Science by: Craig Parsons Chairperson Karrie Koesel Member Tuong Vu Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation; Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2013 ii © 2013 Margaret J. Abney iii THESIS ABSTRACT Margaret J. Abney Master of Arts Department of Political Science June 2013 Title: Avoiding the Arab Spring? The Politics of Legitimacy in King Mohammed VI’s Morocco During the 2011 Arab Spring protests, the Presidents of Egypt and Tunisia lost their seats as a result of popular protests. While protests occurred in Morocco during the same time, King Mohammed VI maintained his throne. I argue that the Moroccan king was able to maintain his power because of factors that he has because he is a king. These benefits, including dual religious and political legitimacy, additional control over the military, and a political situation that make King Mohammed the center of the Moroccan political sphere, are not available to the region’s presidents. -

Psychiatric Healthcare in Morocco: Affordability and Accessibility for Lower

Psychiatric Healthcare in Morocco: Affordability and Accessibility for Lower- Class Moroccans By: Julia Milks Humanities and Arts Course Sequence: AB 2542, Culture of Arabic Speaking Countries, D19 AB 1531, Elementary Arabic I, A19 AB 1532, Elementary Arabic II, B19 HU 2999, Moroccan Arabic, C20 HU 3999, Moroccan Film in Context, C20 Presented to: Professor Rebecca Moody Department of Humanities & Arts C20 HU 3900 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Humanities & Arts Requirement Worcester Polytechnic Institute Worcester, Massachusetts 2 Abstract The Moroccan healthcare system is severely lacking in finances, staff, and resources for psychiatric care. In this paper, I aim to show the lack of accessibility and affordability of psychiatric care for lower-class Moroccans. I conducted interviews at Ibn Al Hassan Mental Hospital in Fes, Morocco that helped me determine that psychiatric care in public hospitals is lower quality due to the lack of resources and funding dedicated to the system, rather than incompetent medical professionals. 3 Introduction In Morocco, the first response is ‘she’s possessed.’ In the U.S., ‘she’s faking it for attention.’ Mental health is a stigmatized topic that brings many layers of shame, confusion, and negativity onto the sufferer. In this paper, I will focus on mental health1 in Morocco, although this problem is not specific to Morocco, the U.S., or any country: it is prevalent everywhere. Morocco severely lacks the tools and manpower needed to administer proper psychiatric care to the millions of people who need it.2 This problem is especially apparent in rural and poor areas. In this paper, I will argue that Moroccans of a lower socioeconomic class receive lower quality psychiatric healthcare due to the limited affordability and access to medications and hospitals; I will draw on my observations of one psychiatric hospital in Fes. -

To View Online Click Here

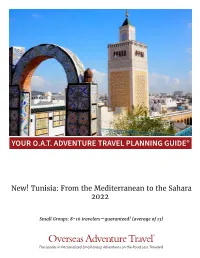

YOUR O.A.T. ADVENTURE TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE® New! Tunisia: From the Mediterranean to the Sahara 2022 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 13) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Personalized Small Group Adventures on the Road Less Traveled 1 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. And the O.A.T. New! Tunisia: From the Mediterranean to the Sahara itinerary you’ve expressed interest in will be a wonderful way to resume the discoveries that bring us so much joy. You might soon be enjoying standout moments like these: Venture out to the Tataouine villages of Chenini and Ksar Hedada. In Chenini, your small group will interact with locals and explore the series of rock and mud-brick houses that are seemingly etched into the honey-hued hills. After sitting down for lunch in a local restaurant, you’ll experience Ksar Hedada, where you’ll continue your people-to-people discoveries as you visit a local market and meet local residents. You’ll also meet with a local activist at a coffee shop in Tunis’ main medina to discuss social issues facing their community. You’ll get a personal perspective on these issues that only a local can offer. The way we see it, you’ve come a long way to experience the true culture—not some fairytale version of it. So we keep our groups small, with only 8-16 travelers (average 13) to ensure that your encounters with local people are as intimate and authentic as possible. -

Algeria Cultural Discovery

Algeria Cultural Discovery 9 Days Algeria Cultural Discovery Take the road less traveled on this incredible adventure in Algeria — one of the least visited countries in the world! Experience the rare beauty of cosmopolitan Algiers, with its historic Casbah and labyrinthine old quarter. Then explore the impressive and well-preserved Roman ruins at Tipasa, beautifully situated on the Mediterranean, and Timgad. Travel deep into the heart of the M'Zab Valley and explore its enchanting fortress cities rising from the dunes. With deep history and ancient UNESCO-listed relics at every step, you'll find yourself in a fascinating land wondering why it wasn't on your radar sooner. Details Testimonials Arrive: Algiers, Algeria “We have traveled throughout the world, but never experienced a level of service and attention to detail Depart: Algiers, Algeria as we did with MT Sobek.“ Dennis G. Duration: 9 Days Group Size: 4-12 Guests “I have taken 12 trips with MT Sobek. Each has left a positive imprint on me—widening my view of the Minimum Age: 14 Years Old world and its peoples.” Jane B. Activity Level: . REASON #01 REASON #02 REASON #03 MT Sobek captures the best Our team of local guides This 9-day adventure has been of Algeria on this unique and are true experts and have crafted to pair effortlessly with immersive insider adventure decades of experience leading a 6-day extension to help you spanning the country's guests through Algeria. maximize your time in Algeria. historical and cultural wonders. ACTIVITIES LODGING CLIMATE In-depth cultural touring, including Luxurious 4- and 5-star hotels Algeria's coastal areas have a exploring five UNESCO World with elegant rooms and typical Mediterranean climate Heritage wonders and enjoying scenic locations - all carefully with warm, dry summers authentic local encounters. -

Morocco and United States Combined Government Procurement Annexes

Draft Subject to Legal Review for Accuracy, Clarity, and Consistency March 31, 2004 MOROCCO AND UNITED STATES COMBINED GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT ANNEXES ANNEX 9-A-1 CENTRAL LEVEL GOVERNMENT ENTITIES This Chapter applies to procurement by the Central Level Government Entities listed in this Annex where the value of procurement is estimated, in accordance with Article 1:4 - Valuation, to equal or exceed the following relevant threshold. Unless otherwise specified within this Annex, all agencies subordinate to those listed are covered by this Chapter. Thresholds: (To be adjusted according to the formula in Annex 9-E) For procurement of goods and services: $175,000 [Dirham SDR conversion] For procurement of construction services: $ 6,725,000 [Dirham SDR conversion] Schedule of Morocco 1. PRIME MINISTER (1) 2. NATIONAL DEFENSE ADMINISTRATION (2) 3. GENERAL SECRETARIAT OF THE GOVERNMENT 4. MINISTRY OF JUSTICE 5. MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND COOPERATION 6. MINISTRY OF THE INTERIOR (3) 7. MINISTRY OF COMMUNICATION 8. MINISTRY OF HIGHER EDUCATION, EXECUTIVE TRAINING AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH 9. MINISTRY OF NATIONAL EDUCATION AND YOUTH 10. MINISTRYOF HEALTH 11. MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND PRIVATIZATION 12. MINISTRY OF TOURISM 13. MINISTRY OF MARITIME FISHERIES 14. MINISTRY OF INFRASTRUCTURE AND TRANSPORTATION 15. MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT (4) 16. MINISTRY OF SPORT 17. MINISTRY REPORTING TO THE PRIME MINISTER AND CHARGED WITH ECONOMIC AND GENERAL AFFAIRS AND WITH RAISING THE STATUS 1 Draft Subject to Legal Review for Accuracy, Clarity, and Consistency March 31, 2004 OF THE ECONOMY 18. MINISTRY OF HANDICRAFTS AND SOCIAL ECONOMY 19. MINISTRY OF ENERGY AND MINING (5) 20. -

Du Ceri Centre D'études Et De Recherches

les études du Ceri Centre d’Études et de Recherches Internationales Algeria: The Illusion of Oil Wealth Luis Martinez Algeria: The Illusion of Oil Wealth Abstract Thirty years after the nationalization of hydrocarbons Algeria’s oil wealth seems to have disappeared judging by its absence in the country’s indicators of well-being. In Algeria, oil brought happiness to a few and misery for many. The lack of oversight over oil revenue led to the industries downfall. Since 2002, oil wealth has returned to Algeria. The per-barrel price increase from $30 to $147 between 2002 and 2008 provided the country with unexpected revenue enabling it to accumulate an estimated $150 billion in dollar reserves, in 2009. Abdelaziz Bouteflika, who returned to a devastated Algeria to restore civil order, unexpectedly benefited from this price increase. Thus, he was able to offer Algeria not only national reconciliation but also renewed economic growth. However, given that the wounds of the 1990s are not entirely healed and the illusions of oil wealth have evaporated with the randomness of economic instability, this unexpected return of financial abundance raises concerns. To what ends will this windfall be put? Who will control it? Will it provoke or sustain a renewal of violence and conflict? Les illusions de la richesse pétrolière Résumé Trente ans après la nationalisation des hydrocarbures, la richesse pétrolière accumulée semble disparue tant elle est absente des indicateurs d’évaluation du bien être. En Algérie, elle a fait le bonheur d’une minorité et la tristesse de la majorité. L’absence de contrôle exercé sur la rente pétrolière a conduit à sa dilapidation. -

Morocco Administrative Structure

INFORMATION PAPER Morocco: Administrative Structure On 20 February 2015 the Moroccan government issued Decree No. 2-15-401, outlining the modified administrative structure of the country. This reorganisation is the result of a government programme aimed at giving each of the regions autonomy, and a greater autonomy to the regions coinciding with Western Sahara. In 2010, the Consultative Commission for Regionalization was formed to tackle this subject. The commission prepared a report proposing to reorganize Morocco into 12 regions. The new 12-region structure constitutes a regrouping of the existing provinces and prefectures2 and replaces the previous structure of 16 regions. The decree states that Morocco is divided into 12 regions. However, since Dakhla-Oued Ed-Dahab3 falls entirely in the territory of Western Sahara4, this would not be included on UK products as part of Morocco. The region of Laâyoune-Sakia El Hamra falls partly into Western Sahara but as part of it is in Morocco, it is recognised as part of Morocco’s administrative structure and the part outside Western Sahara can be shown on UK mapping. Administrative Regions of Morocco (as of February 2015) Prefectures & Provinces Region (ADM1) Administrative Centre (PPLA) (ADM2s) 1. Tanger-Assilah* 2. M’diq-Fnideq* 3. Tétouan Tanger-Assilah# Tanger-Tétouan-Al 4. Fahs-Anjra 1 Hoceïma 5. Larache (Tanger (Tangiers)) 6. Al Hoceïma 7. Chefchaouen 8. Ouezzane 1. Oujda-Angad* 2. Nador 3. Driouch # Oujda-Angad 4. Jerada 2 L’Oriental 5. Berkane (Oujda) 6. Taourirt 7. Guercif 8. Figuig 1http://www.pncl.gov.ma/fr/EspaceJuridique/DocLib/d%C3%A9cret%20fixant%20le%20nombre%20des%20r% C3%A9gions.pdf 2 http://www.regionalisationavancee.ma/PagesmFr.aspx?id=54; http://www.regionalisationavancee.ma/PDF/Rapport/Fr/regionFr.pdf 3 The Moroccan Decree states that Oued Ed-Dahab is the administrative centre of this region, which is subdivided into two provinces (ADM2s): Oued Ed-Dahab and Aousserd). -

Curriculum Vitae Dr

Curriculum Vitae Dr. Nadjib Benkheira Department of Islamic History and Civilization University of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates 2017 Place of Birth: Bou Saâda, Algeria Academic Qualifications: Fine Field of Specialization: History of the Abbasid Period (132 Hijri – 656 Hijri) Major Field of Specialization: Islamic History / Islamic Civilization 2004: Ph.D., History and Islamic Civilization with Honors, and commendation by the discussion committee, Islamic History Department, Emir Abdelkader University of Islamic Sciences, University of Constantine, Algeria 1995: Master’s in Islamic History and Civilization with Honors, Islamic History Department, Emir Abdelkader University of Islamic Sciences, University of Constantine, Algeria 1990: Bachelor of Arts in Islamic History, Islamic Civilization Institute, Emir Abdelkader University of Islamic Sciences, University of Constantine, Algeria (1st in the cohort) Rank: Associate Professor in Islamic History and Civilization, University of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates Research Interests: - Islamic History (1 Hijri – 656 Hijri) - Civil History - History of Sciences in Islamic Civilization - Contemporary Islamic Thought - 1 Membership of Professional Bodies: Member of Arab Historians’ Association Member of Algerian Historians’ Association Member of Algerian Writers’ Association Member of the Scientific Council of the Center for Research in Islamic Sciences and Civilization, Algeria Administrative Responsibilities: - Head of Department of Islamic History and Civilization, University of Sharjah, September 2016 to present - Academic Vice Assistant to the Assistant of the Chancellor for Branches’ Affairs, February 2013 to February 2016 - Coordinator for the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, Khor Fakkan Branch, University of Sharjah, December 2009 to 2013 - Secretary for Council of Scientific Branches, Khor Fakkan, University of Sharjah, 2008 to 2009 Published Books: 1. -

1 LESSONS from an ARAB by John Kiser Introduction I Owe My Interest

LESSONS FROM AN ARAB ( Abdelkader’s Legacy of Empathy and Obedience, 1808-1883) by John Kiser Introduction I owe my interest in Emir Abdelkader to a community of French Trappist monks living in the Atlas Mountains, south of Algiers. The story of their kidnapping in 1996 and eventual death became the subject of a book, The Monks of Tibhirine : Faith, Love and Terror in Algeria. Seven years later, an award- winning French film, Of Men and Gods, was produced based in large measure on the book. Brought to the more God-fearing United States by Sony Classics, it became Of Gods and Men. By a coincidence of history, their monastery of Notre Dame of the Atlas was located below a cliff face called Abdelkader Rock. Curious about the name, I learned from the monks that Abdelkader had once directed a battle against the French from the top of the cliff and is considered by Algerians to be their version of George Washington. Abdelkader was the first Arab leader to unify tribes, however briefly, into a proto-Arab state to resist a French occupation that began with the sack of Algiers in 1830. As it turned out, the emir’s struggle was but the first phase of a “long war” for independence and dignity that lasted until 1962. As I read more about him, I also noted his resemblance to other Americans--- Robert E. Lee and John Winthrop. Like Lee, he was deeply religious, gracious, unwilling to prolong senseless suffering and in defeat, promoted reconciliation. Like Winthrop, Abdelkader believed that good governance required submission to Divine Law: God’s wisdom as revealed through the prophets in the Torah, the Psalms, the Gospels and the Koran— interpreted through the actions and sayings of the Prophet Mohammad, known as the Sunna.