Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Misconceptions About the Baroque Violin

Pollens: Some Misconceptions about the Baroque Violin Some Misconceptions about the Baroque Violin Stewart Pollens Copyright © 2009 Claremont Graduate University Much has been written about the baroque violin, yet many misconceptions remain²most notably that up to around 1750 their necks were universally shorter and not angled back as they are today, that the string angle over the bridge was considerably flatter, and that strings were of narrower gauge and under lower tension.1 6WUDGLYDUL¶VSDWWHUQVIRUFRQVWUXFWLQJQHFNVILQJHUERDUGVEULGJHVDQG other fittings preserved in the Museo Stradivariano in Cremona provide a wealth of data that refine our understanding of how violins, violas, and cellos were constructed between 1666- 6WUDGLYDUL¶V\HDUV of activity). String tension measurements made in 1734 by Giuseppe Tartini provide additional insight into the string diameters used at this time. The Neck 7KHEDURTXHYLROLQ¶VWDSHUHGQHFNDQGZHGJH-shaped fingerboard became increasingly thick as one shifted from the nut to the heel of the neck, which required the player to change the shape of his or her hand while moving up and down the neck. The modern angled-back neck along with a thinner, solid ebony fingerboard, provide a nearly parallel glide path for the left hand. This type of neck and fingerboard was developed around the third quarter of the eighteenth century, and violins made in earlier times (including those of Stradivari and his contemporaries) were modernized to accommodate evolving performance technique and new repertoire, which require quicker shifts and playing in higher positions. 7KRXJK D QXPEHU RI 6WUDGLYDUL¶V YLROD DQG FHOOR QHFN SDWWHUQV DUH SUHVHUYHG LQ WKH 0XVHR Stadivariano, none of his violin neck patterns survive, and the few original violin necks that are still mounted on his instruments have all been reshaped and extended at the heel so that they could be mortised into the top block. -

Tuning Ancient Keyboard Instruments - a Rough Guide for Amateur Owners

Tuning Ancient Keyboard Instruments - A Rough Guide for Amateur Owners. Piano tuning is of course a specialized and noble art, requiring considerable skill and training. So it is presumptuous for me to offer any sort of Pocket Guide. However, it needs to be recognized that old instruments (and replicas) are not as stable as modern iron-framed pianos, and few of us can afford to retain the services of a professional tuner on a frequent basis. Also, some of us may be restoring old instruments, or making new ones, and we need to do something. So, with apologies to the professionals, here is a short guide for amateurs. If you know how to set a temperament by ear, and know what that means, please read no further. But if not, a short introductory background might be useful. Some Theory We have got used to music played in (or at least based around) the major and minor scales, which are in turn descended from the ancient modes. In these, there are simple mathematical ratios between the notes of the scale, which are the basis of our perception of harmony. For example, the frequency of the note we call G is 3/2 that of the C below. This interval is a pure, or perfect fifth. When ratios are not exact, we hear ‘beats’, as the two notes come in and out of phase. For example, if we have one string tuned to A415 (cycles per second, or ‘Hertz’ and its neighbour a bit flat at A413, we will hear ‘wow-wow-wow’ beats at two per second. -

Giovanni Ferrini Dell’Accademia Internazionale Giuseppe Gherardeschi Di Pistoia

Ottaviano Tenerani LO SPINETTONE FIRMATO GIOVANNI FERRINI DELL’ACCADEMIA INTERNAZIONALE GIUSEPPE GHERARDESCHI DI PISTOIA Presso l’Accademia Internazionale d’Organo e di Musica Antica Giuseppe Gherardeschi di Pistoia si conserva uno spinettone apparentemente realiz- zato nel 1731 da Giovanni Ferrini (fig. 1).1 Figura 1. Lo spinettone di Pistoia, Accademia Internazionale d’Organo e di Musica Antica ‘Giuseppe Gherardeschi’. Foto dell’autore. 1 Questo strumento è già stato descritto in Stewart Pollens, ‘Three keyboard instruments signed by Cristofori’s assistant, Giovanni Ferrini’, The Galpin Society Journal XLIV, 1991, 77–93: 80 e sgg. Si veda anche Stewart Pollens, Bartolomeo Cristofori and the invention of the 111 Ottaviano Tenerani Si tratta di uno dei tre strumenti di questo tipo attualmente conosciuti, insieme ai suoi consimili attribuiti rispettivamente a Bartolomeo Cristofori (Museum für Musikinstrumente der Universität Leipzig, Lipsia, inv. n. 86) e al pisano Giuseppe Solfanelli (Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History, Washington D.C., inv. n. 60.1395).2 In questo breve scritto si renderà conto della storia del ritrovamento dello strumento di Pistoia, del suo ripristino funzionale e dei contesti ad oggi conosciuti riguardanti il suo utilizzo storico. Partendo dalle differenze tra i tre spinettoni ad oggi noti, proporremo inoltre alcune riflessioni sul suo funzionamento e sul possibile uso musicale dei registri, in particolare del 4 piedi. Origine dello strumento La storia del ritrovamento di questo strumento inizia nei primissimi anni Sessanta del Novecento quando il Capitolo di Pistoia decise di mettere in vendita il materiale che si trovava nelle soffitte del duomo, in locali a fine- stratura aperta e quindi parzialmente esposti alle intemperie. -

The Basics of Harpsichord Tuning Fred Sturm, NM Chapter Norfolk, 2016

The Basics of Harpsichord Tuning Fred Sturm, NM Chapter Norfolk, 2016 Basic categories of harpsichord • “Historical”: those made before 1800 or so, and those modern ones that more or less faithfully copy or emulate original instruments. Characteristics include use of simple levers to shift registers, relatively simple jack designs, use of either quill or delrin for plectra, all-wood construction (no metal frame or bars). • 20th century re-engineered instruments, applying 20th century tastes and engineering to the basic principle of a plucked instrument. Pleyel, Sperrhake, Sabathil, Wittmeyer, and Neupert are examples. Characteristics include pedals to shift registers, complicated jack designs, leather plectra, and metal frames. • Kit instruments, many of which fall under the historical category. • A wide range of in between instruments, including many made by inventive amateurs. Harpsichords come in many shapes and designs. • They may have one keyboard or two. • They may have only one string per key, or as many as four. • The pitch level of each register of strings may be standard, or an octave higher or lower. These are called, respectively, 8-foot, 4-foot, and 16-foot. • The harpsichord may be designed for A440, for A415, or possibly for some other pitch. • Tuning pins may be laid out as in a grand piano, or they may be on the side of the case. • When there are multiple strings per note, the different registers may be turned on and off using levers or pedals. We’ll start by looking at some of these variables, and how that impacts tuning. Single string instruments These are the simplest instruments, and the easiest to tune. -

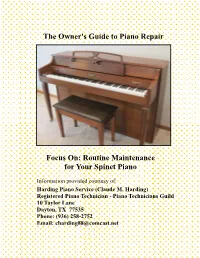

Routine Maintenance for Your Spinet Piano

The Owner's Guide to Piano Repair Focus On: Routine Maintenance for Your Spinet Piano Information provided courtesy of: Harding Piano Service (Claude M. Harding) Registered Piano Technician - Piano Technicians Guild 10 Taylor Lane Dayton, TX 77535 Phone: (936) 258-2752 Email: [email protected] As the owner of a spinet piano you have the advantage of playing on an authentic acoustic piano which is conveniently sized–approximately the same dimensions as a digital piano . A spinet is often a good option for the home owner or apartment dweller who doesn't have an abundance of space, but who wants a real piano to play. With proper maintenance, a good quality spinet piano can be a reliable instrument that provides years of musical enjoyment. Sitting down to play on a freshly tuned spinet can be a pleasant experience for beginners and more advanced pianists alike! The following information is intended to enable you to better understand the proper maintenance required to keep your spinet piano in top form. Tuning: As with any acoustic piano, following a regular tuning schedule is es- sential for a spinet piano to perform up to its potential . All pianos go out of tune over time because of a variety of factors such as seasonal swings in humidity lev- els. An important key to your spinet piano sounding its best is to keep it in proper tune by having it professionally serviced on a regular basis. An adequate tuning schedule for a piano being used frequently is a once-a-year tuning, usually sched- uled for approximately the same time of year each year. -

A Brief History of Piano Action Mechanisms*

Advances in Historical Studies, 2020, 9, 312-329 https://www.scirp.org/journal/ahs ISSN Online: 2327-0446 ISSN Print: 2327-0438 A Brief History of Piano Action Mechanisms* Matteo Russo, Jose A. Robles-Linares Faculty of Engineering, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK How to cite this paper: Russo, M., & Ro- Abstract bles-Linares, J. A. (2020). A Brief History of Piano Action Mechanisms. Advances in His- The action mechanism of keyboard musical instruments with strings, such as torical Studies, 9, 312-329. pianos, transforms the motion of a depressed key into hammer swing or jack https://doi.org/10.4236/ahs.2020.95024 lift, which generates sound by striking the string of the instrument. The me- Received: October 30, 2020 chanical design of the key action influences many characteristics of the musi- Accepted: December 5, 2020 cal instrument, such as keyboard responsiveness, heaviness, or lightness, which Published: December 8, 2020 are critical playability parameters that can “make or break” an instrument for a pianist. Furthermore, the color of the sound, as well as its volume, given by Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. the shape and amplitude of the sound wave respectively, are both influenced This work is licensed under the Creative by the key action. The importance of these mechanisms is highlighted by Commons Attribution International centuries of studies and efforts to improve them, from the simple rigid lever License (CC BY 4.0). mechanism of 14th-century clavichords to the modern key action that can be http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ found in concert grand pianos, with dozens of bodies and compliant elements. -

Harpsichords and Spinets Shown at the International Inventions Exhibition 1885 Royal Albert Hall

Harpsichords and Spinets shown at the International Inventions Exhibition 1885 Royal Albert Hall By David Hackett From a Presentation made at the Friends of Square Pianos Spinet Day, April 8th 2017 The 1885 International Inventions Exhibition was a major affair, occupying a large site to the south of the Royal Albert Hall, including the area where the Royal College of Music now stands, and extending considerably beyond it. The Loan Collection of Musical Instruments was a very small part of the show, but nevertheless it was probably the best collection of early keyboard instruments ever displayed – we are unlikely to see anything like it again. This list of sixty-five harpsichords and spinets has been compiled from the Catalogue of the Exhibition, with later research to establish where possible the identity of the instruments, their subsequent history, and their current whereabouts. A number of early pianos and clavichords were shown as well, but there is usually insufficient information to enable individual identification. The principal source of information is the catalogue of the exhibition, prepared by A. J. Hipkins, and printed and published by William Clowes and Sons, 1885. The page numbers given refer to this catalogue. Notes arising from more recent research are in italics. 1 – CLAVECIN by A Ruckers, Antwerp, 1636. Lacquer case. Restored by Pascal Taskin, Paris, 1782. The Clavecin (French) Clavicembalo (Italian) Harpsichord (English) is wing-shaped, and has two or three strings to each note, while the Spinet. Trapeze-shaped and Virginal, oblong, have each only one. It appeared first in the 16th century, and the oldest known is a Roman Clavicenbalo in South Kensington Museum, dated 1521. -

C:\My Documents II\09Th Conference Winternitz\Abstract Booklet\01Title

THE RESEARCH CENTER FOR MUSIC ICONOGRAPHY and THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART Music in Art: Iconography as a Source for Music History THE NINTH CONFERENCE OF THE RESEARCH CENTER FOR MUSIC ICONOGRAPHY, COMMEMORATING THE 20TH ANNIVERSARY OF DEATH OF EMANUEL WINTERNITZ (1898–1983) New York City 5–8 November 2003 Cosponsored by AUSTRIAN CULTURAL FORUM NEW YORK http://web.gc.cuny.edu/rcmi CONTENTS Introduction 1 Program of the conference 4 Concerts Iberian Piano Music and Its Influences 12 An Evening of Victorian Parlour Music 16 Abstracts of papers 23 Participants 41 Research Center for Music Iconography 45 Guidelines for authors 46 CONFERENCE VENUES Baisley Powell Elebash Recital Hall & Conference Room 9.204 The City University of New York, The Graduate Center, 365 Fifth Avenue Uris Auditorium The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue Austrian Cultural Forum 11 East 52nd Street Proceedings of the conference will be published in forthcoming issues of the journal Music in Art. ********************************************************************************* Program edited and conference organized by ZDRAVKO BLAŽEKOVIĆ THE RESEARCH CENTER FOR MUSIC ICONOGRAPHY The Barry S. Brook Center for Music Research and Documentation The City University of New York, The Graduate Center 365 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10016-4309 Tel. 212-817-1992 Fax 212-817-1569 eMail [email protected] © The Research Center for Music Iconography 2003 The contents was closed on 21 September 2003 MUSIC IN ART: ICONOGRAPHY AS A SOURCE FOR MUSIC HISTORY After its founding in 1972, the Research Center for Music Iconography used to annually organize conferences on music iconography. The discipline was still young, and on the programs of these meetings – cosponsored by the Répertoire International d’Iconographie Musicale and held several times under the auspices of the Greater New York Chapter of the American Musicological Society – there were never more than a dozen papers. -

The Interwoven Evolution of the Early Keyboard and Baroque Culture

Musical Offerings Volume 7 Number 1 Spring 2016 (Special Issue) Article 4 4-11-2016 The Interwoven Evolution of the Early Keyboard and Baroque Culture Rachel Stevenson Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Music Theory Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Stevenson, Rachel (2016) "The Interwoven Evolution of the Early Keyboard and Baroque Culture," Musical Offerings: Vol. 7 : No. 1 , Article 4. DOI: 10.15385/jmo.2016.7.1.4 Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings/vol7/iss1/4 The Interwoven Evolution of the Early Keyboard and Baroque Culture Document Type Article Abstract The purpose of this paper is to analyze the impact that Baroque society had in the development of the early keyboard. While the main timeframe is Baroque, a few references are made to the late Medieval Period in determining the reason for the keyboard to more prominently emerge in the musical scene. As Baroque society develops and new genres are formed, different keyboard instruments serve vital roles unique to their construction. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09657-8 — Bartolomeo Cristofori and the Invention of the Piano Stewart Pollens Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09657-8 — Bartolomeo Cristofori and the Invention of the Piano Stewart Pollens Index More Information Index Academie´ royale des sciences, 328, 329, 330 Beck, Frederick, 345 Accademia Patavina, 9 Beethoven, Ludwig van, 338 Adlung, Jakob, 290, 291, 305, 363 Berni, Agnolo, 24 Agricola, Johann Friedrich, 288, 290 Berti, Antonfrancesco, 18 Agricola, Martin, 292 Berti, Niccolo,` 18, 30, 40, 57, 58, 220, 241 Alberti, Domenico, 346 Beyer, Adam, 345 Albizzi, Luca Casimiro degli, 28 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 73, 221 Albizzi, Rinaldo degli, 28 Biblioteca Capitolare, Verona, 350 Amati, family of violin makers, 224 Biblioteca del Conservatorio di Musica “Luigi Amati, Nicolo,` 10 Cherubini”, 235 Antonius Patavinus, 13 Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, 220, 221 Antunes, 262, 265, 266, 267, 268, 270, 271, 272, Bibliothek des Priesterseminars, 221 273, 274, 275, 276, 278, 280 Bitter, Carl Hermann, 308 Antunes, Joachim Joze,´ 249, 264, 265, 275 Bitti, Martino, 24, 32, 68, 212, 218, 219, 220, Antunes, Manuel, 249, 264, 267 222, 223, 224, 226, 234, 235 Aranjuez, Palace at, 246, 247, 248 Blanchet, Franc¸ois-Etienne´ II, 331 Arpicimbalo . che fa’ il piano, e il forte, 15, 66, Boalch, Donald H., 332, 363 72, 119, 120 Bolgioni, Antonio, 16 Art du faiseur d’instruments de musique et Brancour, Rene,´ 333 lutherie, 334 Broadwood, John, 346 Assolani, Francesco, 24, 219, 222, 223, 224 Brown, Mrs. John Crosby, 159 Augustus I, Frederick, 284 Bruschi (Brischi), Bartolommeo, 24, 219, 222 Buechenberg, Matheus, 33 Babel, William, -

Volume I March 1948

Complete contents of GSJs I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI XXXII XXXIII XXXIV XXXV XXXVI XXXVII XXXVIII XXXIX XL XLI XLII XLIII XLIV XLV XLVI XLVII XLVIII XLIX L LI LII LIII LIV LV LVI LVII LVIII LIX LX LXI LXII LXIII LXIV LXV LXVI LXVII LXVIII LXIX LXX LXXI LXXII LXXIII GSJ Volume LXXIII (March 2020) Editor: LANCE WHITEHEAD Approaching ‘Non-Western Art Music’ through Organology: LAURENCE LIBIN Networks of Innovation, Connection and Continuity in Woodwind Design and Manufacture in London between 1760 and 1840: SIMON WATERS Instrument Making of the Salvation Army: ARNOLD MYERS Recorders by Oskar Dawson: DOUGLAS MACMILLAN The Swiss Alphorn: Transformations of Form, Length and Modes of Playing: YANNICK WEY & ANDREA KAMMERMANN Provenance and Recording of an Eighteenth-Century Harp: SIMON CHADWICK Reconstructing the History of the 1724 ‘Sarasate’ Stradivarius Violin, with Some Thoughts on the Use of Sources in Violin Provenance Research: JEAN-PHILIPPE ECHARD ‘Cremona Japanica’: Origins, Development and Construction of the Japanese (née Chinese) One- String Fiddle, c1850–1950: NICK NOURSE A 1793 Longman & Broderip Harpsichord and its Replication: New Light on the Harpsichord-Piano Transition: JOHN WATSON Giovanni Racca’s Piano Melodico through Giovanni Pascoli’s Letters: GIORGIO FARABEGOLI & PIERO GAROFALO The Aeolian harp: G. Dall’Armi’s acoustical investigations (Rome 1821): PATRIZIO BARBIERI Notes & Queries: A Late Medieval Recorder from Copenhagen: -

Maffei's Article and the Drawing of Cristofori's Piano Action

Differences between Maffei’s article on Cristofori’s piano in its 1711 and 1719 versions, their subsequent transmission and the implications. Denzil Wraight, Version 1.41, dated 7 Jan 2017, www.denzilwraight.com/Maffei.pdf Abstract: Although many publications provide a drawing ( disegno ) of Cristofori's piano action and describe it as from the 1711 edition of Maffei's article, most are in fact from altered versions: three altered from the 1711 edition and five from the 1719 edition. The original version has only been re-produced (albeit incompletely) by Rattalino. The 1711 drawing shows an action which is feasible, whereas some versions are functionally impossible. An examination of the text, and of surviving actions, strengthens the argument, already advanced by Och, that Maffei did not write the technical description of the action, but received a report from Cristofori. It is argued here that the other details concerning the nature of the newly-invented Gravecembalo col piano, e forte and its use were also provided by Cristofori. Thus, these testify to the maker's intentions, which are significant for us now in understanding the first piano. Maffei's unpublished notes for the article give some insight into Cristofori's early days in Florence, but do not support the interpretation that Cristofori initially declined to work for Prince Ferdinando de' Medici. Keywords: Cristofori, piano action, Maffei, disegno, Rattalino, Och, Gravecembalo , Ferdinando de' Medici . Scipione Maffei’s article on Cristofori’s piano published anonymously in 1711 as Nuova invenzione d’un Gravecembalo col piano, e forte… was re- published in 1719 in a collection of some of his writings as Descrizione D’un Gravicembalo Col Piano, E Forte.… 1.