Concentration Camp Riga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20 Dokumentar Stücke Zum Holocaust in Hamburg Von Michael Batz

„Hört damit auf!“ 20 Dokumentar stücke zum Holocaust in „Hört damit auf!“ „Hört damit auf!“ 20 Dokumentar stücke Hamburg Festsaal mit Blick auf Bahnhof, Wald und uns 20 Dokumentar stücke zum zum Holocaust in Hamburg Das Hamburger Polizei- Bataillon 101 in Polen 1942 – 1944 Betr.: Holocaust in Hamburg Ehem. jüd. Eigentum Die Versteigerungen beweglicher jüdischer von Michael Batz von Michael Batz Habe in Hamburg Pempe, Albine und das ewige Leben der Roma und Sinti Oratorium zum Holocaust am fahrenden Volk Spiegel- Herausgegeben grund und der Weg dorthin Zur Geschichte der Alsterdorfer Anstal- von der Hamburgischen ten 1933 – 1945 Hafenrundfahrt zur Erinnerung Der Hamburger Bürgerschaft Hafen 1933 – 1945 Morgen und Abend der Chinesen Das Schicksal der chinesischen Kolonie in Hamburg 1933 – 1944 Der Hannoversche Bahnhof Zur Geschichte des Hamburger Deportationsbahnhofes am Lohseplatz Hamburg Hongkew Die Emigration Hamburger Juden nach Shanghai Es sollte eigentlich ein Musik-Abend sein Die Kulturabende der jüdischen Hausgemeinschaft Bornstraße 16 Bitte nicht wecken Suizide Hamburger Juden am Vorabend der Deporta- tionen Nach Riga Deportation und Ermordung Hamburger Juden nach und in Lettland 39 Tage Curiohaus Der Prozess der britischen Militärregierung gegen die ehemalige Lagerleitung des KZ Neuengam- me 18. März bis 3. Mai 1946 im Curiohaus Hamburg Sonderbehand- lung nach Abschluss der Akte Die Unterdrückung sogenannter „Ost“- und „Fremdarbeiter“ durch die Hamburger Gestapo Plötzlicher Herztod durch Erschießen NS-Wehrmachtjustiz und Hinrichtungen -

Position Paper No. 4 30 May 2019 FICIL Position Paper on the Transport Sector Issues

Position Paper No. 4 30 May 2019 FICIL Position Paper on the Transport sector issues 1. Executive Summary Effectiveness and transparency of the transport industry and related policies are key components that ensure solid economic growth and stability in regards to the transport sector. The Foreign Investors Council in Latvia (FICIL) appreciates the initiative taken by the Ministry of Transport in outlining future plans to improve said sector, with intention to tackle issues that have been apparent for many years. While looking at the current and future investors, it is important to emphasise sustainable mobility to enable economic growth and promote predictability, integration, continuity, territorial cohesion and openness within the transportation network of Latvia. Further effort is required to ensure a transparent and effective transport sector in Latvia, while also looking forward to the future opportunities that large-scale transport infrastructure projects will bring. FICIL has identified underlying concerns affecting the business environment and investment climate in Latvia when it comes to the current state of the transport sector, as well as awaiting future investment in connection to large scale transport infrastructure projects being realised in the Baltic States. To improve the performance of the transport sector, FICIL would like to highlight these areas requiring action: 1. In terms of improving the existing transportation network environment: 1.1. Analyse the most suitable and effective governance model for transport sector enterprises. Establishment of good corporate governance principles with the goal to improve efficiency, transparency and competitiveness; 1.2. Improve quality, connectivity and maintenance of existing infrastructure; 1.3. Enforcement of existing rules and legislation to reduce shadow economy in transport sector. -

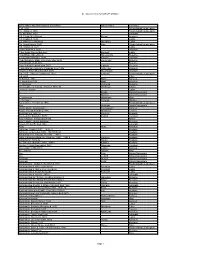

All Latvia Cemetery List-Final-By First Name#2

All Latvia Cemetery List by First Name Given Name and Grave Marker Information Family Name Cemetery ? d. 1904 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? b. Itshak d. 1863 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? b. Abraham 1900 Jekabpils ? B. Chaim Meir Potash Potash Kraslava ? B. Eliazar d. 5632 Ludza ? B. Haim Zev Shuvakov Shuvakov Ludza ? b. Itshak Katz d. 1850 Katz Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? B. Shalom d. 5634 Ludza ? bar Abraham d. 5662 Varaklani ? Bar David Shmuel Bombart Bombart Ludza ? bar Efraim Shmethovits Shmethovits Rezekne ? Bar Haim Kafman d. 5680 Kafman Varaklani ? bar Menahem Mane Zomerman died 5693 Zomerman Rezekne ? bar Menahem Mendel Rezekne ? bar Yehuda Lapinski died 5677 Lapinski Rezekne ? Bat Abraham Telts wife of Lipman Liver 1906 Telts Liver Kraslava ? bat ben Tzion Shvarbrand d. 5674 Shvarbrand Varaklani ? d. 1875 Pinchus Judelson d. 1923 Judelson Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? d. 5608 Pilten ?? Bloch d. 1931 Bloch Karsava ?? Nagli died 5679 Nagli Rezekne ?? Vechman Vechman Rezekne ??? daughter of Yehuda Hirshman 7870-30 Hirshman Saldus ?meret b. Eliazar Ludza A. Broido Dvinsk/Daugavpils A. Blostein Dvinsk/Daugavpils A. Hirschman Hirschman Rīga A. Perlman Perlman Windau Aaron Zev b. Yehiskiel d. 1910 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava Aba Ostrinsky Dvinsk/Daugavpils Aba b. Moshe Skorobogat? Skorobogat? Karsava Aba b. Yehuda Hirshberg 1916 Hirshberg Tukums Aba Koblentz 1891-30 Koblentz Krustpils Aba Leib bar Ziskind d. 5678 Ziskind Varaklani Aba Yehuda b. Shrago died 1880 Riebini Aba Yehuda Leib bar Abraham Rezekne Abarihel?? bar Eli died 1866 Jekabpils Abay Abay Kraslava Abba bar Jehuda 1925? 1890-22 Krustpils Abba bar Jehuda died 1925 film#1890-23 Krustpils Abba Haim ben Yehuda Leib 1885 1886-1 Krustpils Abba Jehuda bar Mordehaj Hakohen 1899? 1890-9 hacohen Krustpils Abba Ravdin 1889-32 Ravdin Krustpils Abe bar Josef Kaitzner 1960 1883-1 Kaitzner Krustpils Abe bat Feivish Shpungin d. -

Regional Stakeholder Group Meeting

Regional Stakeholder Group Meeting Partner/Region: Date: Round: Participants: Main outputs: Riga Planning 03.03.2021. 5th SH Participants: Topics discussed during the meeting: Region (Latvia) meeting In total 21 participants attended an Update on CHERISH activities completed in 2020, online meeting in Zoom platform project activities in 2021; Introduction of CHERISH Action Plan Directions of List of participants: Support; 1. Sanita Paegle; Riga Planning Discussion on selection of actions for CHERISH Region, CHERISH Project Action Plan for Riga Planning Region. Coordinator The main task of the project is to develop an Action 2. Olga Rinkus; Manager of Plan identifying actions that would promote the Carnikava Local History Centre development of coastal fishing communities and the 3. Ilze Turka; Manager of FLAG and protection and promotion of the cultural heritage of Rural Action Group "Partnership fisheries. for Rural and the Sea" 4. Āris Ādlers; Society "The Land of Based on the transnational exchange of experience, Sea/Jūras Zeme", External Expert analysis of the current situation and dialogue with CHERISH project stakeholders, the Riga Planning Region intends to 5. Inta Baumane; Director, Jūrmalas include the following activities in its action plan: City Museum 6. Mārīte Zaļuma; Tourism Action 1: Support for the strengthening of Information of Centre Engure cooperation platforms in coastal fishing Municipality communities for the preservation and promotion of the cultural heritage of fisheries and the 7. Jolanta Kraukle; Engure Parish diversification of the tourism offer: development, Administration commercialization and marketing of new tourism 8. Kristaps Gramanis; Project products, local branding, etc .; Manager of National Fisheries Action 2: Support for capacity building of coastal Cooperation Network museums working to protect and promote the 9. -

Family Vault of the Dukes of Courland

FAMILY VAULT OF THE DUKES OF COURLAND The family vault of the Dukes of Courland is located on the basement-floor level of the south-east corner of Jelgava Palace, seemingly connecting Rastrelli’s building and the old Jelgava medieval castle. The first members of the Kettler family, the Duke Gotthard’s under aged sons, had died in Riga Castle, were buried in Kuldīga and only later brought to Jelgava. The Duke Wilhelm’s wife Sophie who died in 1610 also had been buried in Kuldīga castle church was completed; there was a cellar beneath it for the Dukes’ sarcophagi. The cellar premise was about 9 m wide, with a free passage in the middle and covered by a barrel vault. In 1587, the Duke Gotthard was the first to be buried there; 24 members of the Ket- tler family were buried until 1737. During the Northern War; in September 1705, the crypt was damaged for the first time when Swedish soldiers broke off several sarcophagi and stole jewellery. In 1737 when the castle was blown up, the church and crypt were destroyed as well. Sarcophagi were placed in the shed while the family vault premise was built on the basement floor of the new palace. The new crypt consisted of two rather small vaulted premises on the basement floor of the southern block, with a separate entrance from out- side that was walled up later. The Birons did not realize the idea of a separate family vault. In 1819, a call to the Courland society was announced to donate money for the reconstruction of the Dukes’ family vault. -

Identificación De Criminales De Guerra· Llegados a La Argentina Según Fuentes Locales

Ciclos, Año X, Vol. X, N° 19, 1er. semestre de 2000 Documentos Identificación de criminales de guerra· llegados a la Argentina según fuentes locales Carlota Jackisch* y Daniel Mastromauro** El presente trabajo documenta él ingreso al país de criminales de guerra y responsables de crímenes contra la humanidad, pertenecientes al nazis mo y a regímenes aliados al Tercer Reich, o bajo su ocupación. Se trata de una muestra de 65 casos de un total de 180 individuos detectados, alema nes y de otras nacionalidades, tanto sospechados como encausados, pro cesados o convictos de tales crímenes. Parte de un universo que segura mente excede los 180, la información ofrecidaproviene de la consulta, por vez primera, de fuentes documentales del Ministerio. del Interior (sección documentación personal de la Policía Federal y área certificaciones de la Dirección General de Migraciones.) El relevamiento de tales fuentes se hi zo sobre la base de sus identidades reales o del conocimiento a partir de fuentes extranjeras de las identidades ficticias con que ingresaron al país. Se ofrece a contunuación una sinopsis biográfica de los criminales de gue rra nazis y colaboracionistas que llegaron a la Argentina al finalizar el con flicto bélico. Nazis ALVEN8LEBEN, Ludolf Hermann Dirigente de las SS (Schutzstajjel-Escuadras de Protección Nazis) en Rusia. Su detención fue ordenada por un juzgado de Munich, República Federal de Alema nia, acusado de la matanza de polacos según datos de la Zentraller Stelleder Lan desjustízverwaltung (en adelante Ludwigsburgo), el organismo alemán que .con- * Fundación Konrad Adenauer. ** Universidad de Buenos Aires. 218 Carlota Jackisch y Daniel Mastromauro centra toda la Información que la justicia alemana posee sobre, acusados, de haber cometido delitos relacionados con el accionar delrégimen nacionalsocialista. -

Using Diaries to Understand the Final Solution in Poland

Miranda Walston Witnessing Extermination: Using Diaries to Understand the Final Solution in Poland Honours Thesis By: Miranda Walston Supervisor: Dr. Lauren Rossi 1 Miranda Walston Introduction The Holocaust spanned multiple years and states, occurring in both German-occupied countries and those of their collaborators. But in no one state were the actions of the Holocaust felt more intensely than in Poland. It was in Poland that the Nazis constructed and ran their four death camps– Treblinka, Sobibor, Chelmno, and Belzec – and created combination camps that both concentrated people for labour, and exterminated them – Auschwitz and Majdanek.1 Chelmno was the first of the death camps, established in 1941, while Treblinka, Sobibor, and Belzec were created during Operation Reinhard in 1942.2 In Poland, the Nazis concentrated many of the Jews from countries they had conquered during the war. As the major killing centers of the “Final Solution” were located within Poland, when did people in Poland become aware of the level of death and destruction perpetrated by the Nazi regime? While scholars have attributed dates to the “Final Solution,” predominantly starting in 1942, when did the people of Poland notice the shift in the treatment of Jews from relocation towards physical elimination using gas chambers? Or did they remain unaware of such events? To answer these questions, I have researched the writings of various people who were in Poland at the time of the “Final Solution.” I am specifically addressing the information found in diaries and memoirs. Given language barriers, this thesis will focus only on diaries and memoirs that were written in English or later translated and published in English.3 This thesis addresses twenty diaries and memoirs from people who were living in Poland at the time of the “Final Solution.” Most of these diaries (fifteen of twenty) were written by members of the intelligentsia. -

Promocijas Darba Kopsavilkums : Latvijas Vēsturiskie Dārzi Un Parki

Latvijas Lauksaimniecības universitāte Lauku inženieru fakultāte Arhitektūras un būvniecības katedra Latvia University of Agriculture Faculty of Rural Engineering Department of Architecture and Construction Mg. arch. Kristīne Dreija LATVIJAS VĒSTURISKIE DĀRZI UN PARKI MŪSDIENU LAUKU AINAVĀ HISTORIC GARDENS AND PARKS OF LATVIA IN PRESENT RURAL LANDSCAPE Promocijas darba KOPSAVILKUMS Arhitektūras doktora (Dr.arch.) zinātniskā grāda iegūšanai ainavu arhitektūras apakšnozarē SUMMARY of Doctoral thesis for the scientific degree Dr.arch. in landscape architecture ________________ (paraksts) Jelgava 2013 INFORMĀCIJA Promocijas darbs izstrādāts Latvijas Lauksaimniecības universitātes, Lauku inženieru fakultātes, Arhitektūras un būvniecības katedrā Doktora studiju programma – Ainavu arhitektūra Promocijas darba zinātniskā vadītāja – arhitektūras un būvniecības katedras profesore, Dr.phil. Māra Urtāne Promocijas darba zinātā aprobācija noslēguma posmā: 1. apspriests un aprobēts LLU LIF Arhitektūras un būvniecības katedras personāla pārstāvju sēdē 2012. gada 24. janvārī; 2. apspriests un aprobēts LLU LIF akadēmiskā personāla pārstāvju sēdē 2012. gada 19. jūnijā, un atzīts par sagatavotu iesniegšanai Promocijas padomei; 3. atzīts par pilnībā sagatavotu un pieņemts 2012. gada 8. novembrī. Oficiālie recenzenti: 1. Latvijas Lauksaimniecības universitātes docente, Dr.arch. Daiga Zigmunde 2. Valsts kultūras pieminekļu aizsardzības inspekcijas vadītājs, Dr.arch. Juris Dambis 3. Tartu universitātes profesors, Dr. phil. Simon Bell Promocijas darba aizstāvēšana notiks LLU, ainavu arhitektūras apakšnozares promocijas padomes atklātā sēdē 2013. gada 21. februārī Jelgavā, Lielā ielā 2, Jelgavas pils muzejā (183. telpā), plkst. 16:00 Ar promocijas darbu var iepazīties LLU Fundamentālajā bibliotēkā, Lielā ielā 2, Jelgavā un http://llufb.llu.lv/promoc_darbi.html Atsauksmes sūtīt Promocijas padomes sekretārei – Akadēmijas ielā 19, Jelgavā, LV – 3001, tālrunis 63028791; e-pasts: [email protected] Atsauksmes vēlams sūtīt skanētā veidā ar parakstu. -

Reģions Vārds Un Uzvārds Mobilais Telefons E-Pasts Darba Pieredze Aglonas Novads Jāzeps Gunārs Ruskulis 29529203 Gunars.Rus

Reģions Vārds un uzvārds Mobilais telefons E-pasts Darba pieredze Radio inženieris specialitātē "Radiotehnika". Ir praktiska pieredze un radošs risinājums nestandarta situācijās. Jāzeps Gunārs Prasmes: pieslēgt TV uztveres ierīces (televizorus, virszemes uztvērējus, Aglonas novads 29529203 [email protected] Ruskulis antenas), konfigurēt programmas, salabot ierīces. Konsultēt par ierīču iegādi, lai garantētu 100 % uztveres iespējas jebkurā vietā vai problemātiskas radio redzamības apstākļos. Aizkraukle Aldis Stepiņš 29837131 [email protected] Satelīttelevīzijas meistars sešus gadus. Aizkraukles novads Aigars Zelčs 26329054 [email protected] Seši gadi satelīttelevīzijas instalācijas. Aizkraukles novads Aldis Stepiņš 29837131 [email protected] Satelīttelevīzijas meistars sešus gadus. Aknīste Aigars Zelčs 26329054 [email protected] Seši gadi satelīttelevīzijas instalācijas. Aknīstes novads Aigars Zelčs 26329054 [email protected] Seši gadi satelīttelevīzijas instalācijas. To vien daru, jau 20 gadus. Viss, kas saistīts ar antenām, gan satelītu, gan Alūksne Andris Liepiņš 29142500 [email protected] virszemes. Alūksnes novads Sandis Tutiņš 28377317 [email protected] Virzemes un satelīttelevīzijas meistars. To vien daru, jau 20 gadus. Viss, kas saistīts ar antenām, gan satelītu, gan Alūksnes novads Andris Liepiņš 29142500 [email protected] virszemes. To vien daru, jau 20 gadus. Viss, kas saistīts ar antenām, gan satelītu, gan Apes novads Andris Liepiņš 29142500 [email protected] virszemes. Apes novads Sandis Tutiņš 28377317 [email protected] Virzemes un satelīttelevīzijas meistars. Vitautas Ādažu novads 29691009 [email protected] Antenu, satelītu, ētera TV instalācijas darbi, TV remonts. Pieredze 25 gadi. Andrijauskas Ādažu novads Artūrs Mihailovs 29273780 [email protected] Satelīttelevīzijas antenu un TV antenu ierīkošana, apkope. Antenu, satelītu, ētera TV, videonovērošanas instalācijas darbi. Pieredze 30 Babītes novads Dmitrijs Čeļadinovs 29510395 [email protected] gadi. -

RIGA– MY HOME Handbook for Returning to Live in Riga Content Introduction

RIGA– MY HOME Handbook for Returning to Live in Riga Content Introduction .................................................................................3 Re-emigration coordinator ...............................................................3 Riga City Council Visitor Reception Centre ........................................3 First steps in planning the resettlement ........................................4 Residence permits and the right to employment ..............................6 Learning Latvian ................................................................................7 Supporting children ...........................................................................7 First Steps in Riga .........................................................................8 Identity documents ...........................................................................8 Driving licence ..................................................................................8 Other documents ..............................................................................9 Place of Residence and Housing .................................................. 10 Recommendations for choosing apartments to rent ......................10 Support for purchasing housing ......................................................11 Declaring one’s place of residence ..................................................13 Immovable Property Tax ..................................................................14 Finances, employment and entrepreneurship .............................15 -

The Saeima (Parliament) Election

/pub/public/30067.html Legislation / The Saeima Election Law Unofficial translation Modified by amendments adopted till 14 July 2014 As in force on 19 July 2014 The Saeima has adopted and the President of State has proclaimed the following law: The Saeima Election Law Chapter I GENERAL PROVISIONS 1. Citizens of Latvia who have reached the age of 18 by election day have the right to vote. (As amended by the 6 February 2014 Law) 2.(Deleted by the 6 February 2014 Law). 3. A person has the right to vote in any constituency. 4. Any citizen of Latvia who has reached the age of 21 before election day may be elected to the Saeima unless one or more of the restrictions specified in Article 5 of this Law apply. 5. Persons are not to be included in the lists of candidates and are not eligible to be elected to the Saeima if they: 1) have been placed under statutory trusteeship by the court; 2) are serving a court sentence in a penitentiary; 3) have been convicted of an intentionally committed criminal offence except in cases when persons have been rehabilitated or their conviction has been expunged or vacated; 4) have committed a criminal offence set forth in the Criminal Law in a state of mental incapacity or a state of diminished mental capacity or who, after committing a criminal offence, have developed a mental disorder and thus are incapable of taking or controlling a conscious action and as a result have been subjected to compulsory medical measures, or whose cases have been dismissed without applying such compulsory medical measures; 5) belong -

![Weinberg CV [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3821/weinberg-cv-pdf-973821.webp)

Weinberg CV [Pdf]

ROBERT WEINBERG Isaac H. Clothier Professor of History and International Relations Department of History 500 College Avenue Swarthmore College Swarthmore, Pennsylvania 19081-l397 Office (610) 328-8133 Cell (610) 308-3816 [email protected] Explore a Collection of Soviet Posters From the 1920s and 1930s Housed at Swarthmore College Watch a Video of Boney-M Performing “Rasputin, Russia’s Greatest Love Machine” ACADEMIC DEGREES Ph.D. in History: University of California, Berkeley (1985) M.A. in History: Indiana University (1978) B.S. in Industrial and Labor Relations: Cornell University (1976) ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT Swarthmore College. Assistant Professor: 1988-1994 Associate Professor: 1994-2002 Professor: 2002-Present 1 Department Chair: 1996-2000, 2008-2009, 2011- 2012, 2015-2016, 2019-2022 BOOKS The Four Questions: Jews Under Tsars and Communists (In progress for Bloomsbury Press) Estimated date of completion: Summer 2022 Ritual Murder in Late Imperial Russia: The Trial of Mendel Beilis (Indiana University Press, 2013) Published in Russian as Kровавый навет в последние дни Российской Империи: процесс над Менделем Бейлисом по обвинению в ритуальном убийстве (Academic Studies Press, 2019). Interview with Professor Joan Neuberger (University of Texas, Austin) about Mendel Beilis and the Blood Libel Revolutionary Russia: A History in Documents (Oxford University Press, 2010). Joint authorship with Laurie Bernstein 2 Stalin’s Forgotten Zion: Birobidzhan and the Making of a Soviet Jewish Homeland (University of California Press, 1998). Published in French as Le Birobidjan, 1928-1996 (Paris: Edition Autrement, 2000) and German as Birobidshan: Stalins vergessenes Zion (Frankfurt: Verlag Neue Kritik, 2003). Also served as curator for traveling exhibition about the history of Birobidzhan.