Flemish- and French-Language Television in Belgium in the Face of Globalisation: Matters of Policy and Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reinvention of Club RTL How RTL Belgium’S Number Two Channel Is Being Modernised

24 February 2011 week 08 The reinvention of Club RTL How RTL Belgium’s number two channel is being modernised United Kingdom France FremantleMedia and Random Destination RTL heads House produce children’s formats for southern Spain Netherlands Belgium Radio 538 looks for RTL-TVI portrays Guus Meeuwis’ supporting act the ‘real’ Dr House the RTL Group intranet week 08 24 February 2011 week 08 Cover: Stéphane Rosenblatt, Director of Television, RTL Belgium The reinvention of Club RTL 2 How RTL Belgium’s number two channel is being modernised United Kingdom France FremantleMedia and Random Destination RTL heads House produce children’s formats for southern Spain Netherlands Belgium Radio 538 looks for RTL-TVI portrays Guus Meeuwis’ supporting act the ‘real’ Dr House the RTL Group intranet week 08 “As strong and diverse as possible” RTL Belgium’s Director of Television Stéphane Rosenblatt talks about the evolving Belgian family of channels. Club RTL’s new slogan: Make your choice! Belgium - 17 February 2011 What is the strategy of RTL Belgium? Over the years RTL Belgium has created a strong, tight-knit, complementary family. Strong, because it is the clear leader in the French-speaking market in Belgium, which may be small at 4 million people, but is fiercely competitive because it is also open to French channels. Consequently, the Belgian market poses a real challenge, but this did not prevent RTL Belgium from proudly attaining a combined prime time audience share of 34 per cent in 2010. Tight-knit because our family is full of team spirit. All our teams, whether involved in production or programming, have a transversal culture. -

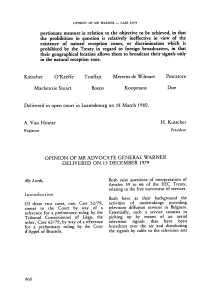

Portionate Measure in Relation to the Objective to Be Achieved, in That The

OPINION OF MR WARNER — CASE 52/79 portionate measure in relation to the objective to be achieved, in that the prohibition in question is relatively ineffective in view of the existence of natural reception zones, or discrimination which is prohibited by the Treaty in regard to foreign broadcasters, in that their geographical location allows them to broadcast their signals only in the natural reception zone. Kutscher O'Keeffe Touffait Mertens de Wilmars Pescatore Mackenzie Stuart Bosco Koopmans Due Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 18 March 1980. A. Van Houtte H. Kutscher Registrar President OPINION OF MR ADVOCATE GENERAL WARNER DELIVERED ON 13 DECEMBER 1979 My Lords, Both raise questions of interpretation of Articles 59 to 66 of the EEC Treaty, relating to the free movement of services. Introduction Both have as their background the Of these two cases, one, Case 52/79, activities of undertakings providing comes to the Court by way of a television diffusion services in Belgium. reference for a preliminary ruling by the Essentially, such a service consists in Tribunal Correctionnel of Liège, the picking up by means of an aerial other, Case 62/79, by way of a reference television signals that have been for a preliminary ruling by the Cour broadcast over the air and distributing d'Appel of Brussels. the signals by cable to the television sets 860 PROCUREUR DU ROI v DEBAUVE of subscribers to the service. We were Counsel for the German Government, told that, from a technical point of view, but he did not press the point, nor would it is only the scale and professionalism of the overall picture have been much the operation (in particular, the size and altered if he had been right. -

015-019 Dossier AB3-5P 6/04/06 18:14 Page 15

015-019 Dossier AB3-5p 6/04/06 18:14 Page 15 dossier dossier AB3 ou le cheval de trop Théo Hachez AB3 ou le cheval de trop Assez tranquille au cours des années nonante, le paysage télévisuel de la Communauté française aura été dérangé, en ce début de millénaire, par l’apparition d’AB3. Les deux canaux des deux opérateurs principaux (La Une et La Deux de la R.T.B.F. et, pour R.T.L./T.V.I., Club R.T.L. et sa chaine éponyme) devront désormais compter avec une chaine gratuite à vocation généraliste de plus et, quelques mois plus tard, avec sa jumelle AB4. L’insignifiance culturelle et l’audience modeste recueillie par les nouvelles venues donnent une faible idée de la menace que leur vraie raison d’être fait peser à terme sur l’assise financière des médias de la Communauté française… Théo Hachez Il faut le dire: personne n’avait vu venir ment fleuri, mais le marché francophone le danger tel qu’il se dessine aujourd’hui. apparaissait trop mince et déjà trop Ni les ministres successifs saisis d’un encombré pour assurer sa viabilité. Au- dossier de reconnaissance au nom de trement dit, même sans pouvoir s’impo- Y.T.V., ni le Conseil supérieur de l’audio- ser comme un concurrent à part entière, visuel (C.S.A.) chargé de l’analyser. Seule Y.T.V. serait de toute façon plus ou moins R.T.L./T.V.I., sur les terres de laquelle un durablement nuisible aux intérêts de projet de télévision généraliste plus ciblé R.T.L./T.V.I. -

Accès Aux Médias Audiovisuels Plateformes & Enjeux

L’accès aux médias audiovisuels Plateformes & enjeux Sommaire 01 PAYSAGE p.7 02 RÉGLEMENTATION p.25 03 CONSOMMATION p.37 04 ENJEUX ÉCONOMIQUES p.51 05 PROTECTION DU CONSOMMATEUR ET DU PUBLIC p.65 06 L’ACCÈS À L’OFFRE p.73 07 ÉVOLUTION DU CADRE RÉGULATOIRE p.89 éditorial Au sens du décret sur les services de médias audiovisuels (SMA), un distributeur de services est une personne qui met à disposition du public un ou des services de médias audiovisuels. Ces services sont généralement édités par d’autres personnes que le distribu- teur, mais ces deux fonctions se confondent de plus en plus, bous- culant la chaîne de valeur traditionnelle. Le distributeur de services joue un rôle fondamental dans l’accès du public à l’offre de SMA. Le distributeur est aussi un vecteur in- contournable pour un nombre croissant d’éditeurs. En pratique, la Dominique Vosters distribution de SMA constitue autant un enjeu démocratique et Président du Conseil supérieur culturel qu’un enjeu économique. Ceci justifie pleinement la régu- de l’audiovisuel lation de ce secteur dans un cadre fixé par les législateurs belges et européen. Après avoir dressé un panorama des différents types de distri- bution disponibles en Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles, le présent Il y a bien longtemps que le public francophone belge s’est habi- ouvrage examinera les divers modes de consommation des SMA tué à recourir à un intermédiaire pour accéder à un SMA. Sans re- qui y sont identifiés, particulièrement ceux qui recourent à de nou- monter à la radio par câble développée à Bruxelles, c’est dans les veaux moyens de distribution. -

Liste Complète Des Chaînes

Liste complète des chaînes Mise à jour: 2 juin 2020 Retrouvez ci-dessous l'ensemble des chaînes disponibles dans nos différents abonnements ainsi que les chaînes disponibles gratuitement (Free to Air) via la télévision numérique par satellite. Important: les chaînes positionnées sur 23,5 et 28,2 (POS) nécessitent une tête LNB spécifique non disponible dans nos packs. Chaînes disponibles dans notre abonnement Live TV. Options Restart & Replay disponibles pour cette chaîne. NR CHAÎNE ABONNEMENT POS FREQ POL SYMB FEC 1 La Une HD Basic Light Basic Basic+ 13.0 10930 H 30000 2/3 2 La Deux Basic Light Basic Basic+ 13.0 10930 H 30000 2/3 3 RTL-TVI HD Basic Light Basic Basic+ 13.0 10930 H 30000 2/3 4 Club RTL / Kidz RTL Basic Light Basic Basic+ 13.0 10930 H 30000 2/3 5 Plug RTL Basic Light Basic Basic+ 13.0 10930 H 30000 2/3 6 La Trois Basic Light Basic Basic+ 13.0 10930 H 30000 2/3 7 AB3 Basic Light Basic Basic+ 19.2 12515 H 22000 5/6 8 C8 HD Basic Light Basic Basic+ 19.2 12207 V 29700 2/3 9 Infosport+ Basic Light Basic Basic+ 19.2 12207 V 29700 2/3 10 TF 1 HD Basic Light Basic Basic+ 13.0 11681 H 27500 3/4 11 France 2 HD Basic Light Basic Basic+ 13.0 11681 H 27500 3/4 12 France 3 Basic Light Basic Basic+ 13.0 11681 H 27500 3/4 13 France 4 Basic Light Basic Basic+ 13.0 11681 H 27500 3/4 14 France 5 Basic Light Basic Basic+ 13.0 11681 H 27500 3/4 15 France Ô Basic Basic+ 13.0 12692 H 27500 3/4 18 TV Breizh HD Basic Basic+ 19.2 12402 V 29700 2/3 19 Comédie+ HD Basic+ 19.2 12441 V 29700 2/3 24 MCM Basic+ 19.2 12402 V 29700 2/3 25 TMC Basic Basic+ -

Paris, Le 26 Mars 2001

CP/42/08 AIRFIELD MEDIA GROUP CHOISIT LA POSITION HOT BIRD™ D’EUTELSAT POUR ASSURER LA DIFFUSION DES CHAINES BELGES FRANCOPHONES DE SON BOUQUET TELESAT Paris, 20 novembre 2008 Eutelsat Communications (Euronext Paris : ETL) a annoncé aujourd’hui la signature avec AIRFIELD MEDIA GROUP d’un contrat de long terme portant sur la location de capacité sur sa position orbitale HOT BIRD™, à 13° Est, et sur les services au sol associés. Les capacités louées à la position phare d’Eutelsat assureront la diffusion des cinq chaînes francophones belges du nouveau bouquet de télévision payante TéléSAT, comprenant RTBF La Une et La Deux, RTL-TVi, Club RTL et PLUG TV. Au-delà de la location de capacité satellitaire sur la position HOT BIRD™, le contrat porte sur la fourniture de liaisons de contribution ainsi que sur le multiplexage et l’émission des cinq chaînes de TéléSAT depuis le téléport d’Eutelsat à Rambouillet (France). Ce service par satellite sera lancé en décembre prochain. La réception des programmes sera accessible sur l’ensemble du territoire belge pour des petites antennes de réception directe associées à des décodeurs MPEG 4 (compatibles MPEG 2) utilisant le système de cryptage Mediaguard 3 de Nagravision. A l’occasion de la signature de ce contrat Kurt Pauwels, Directeur général de TéléSAT a déclaré : « Nous sommes ravis de collaborer avec un opérateur satellite de cette importance pour la création de notre bouquet TéléSAT. Le dynamisme et les nombreuses compétences du groupe Eutelsat, tant en Europe qu'à l'international, ne sont plus à prouver et nous garantissent un service de qualité irréprochable et une solution d'avenir. -

Plan De Fréquences De La Wallonie

Chaines ID RESEAU BRUTELE 1014 1015 1016 1017 1018 1019 1086 1020 1021 Info 502 502 503 503 503 503 504 504 505 cf Onglet Radio MPEG2 MPEG2 MPEG2 MPEG2 MPEG2 MPEG2 MPEG2 MPEG2 MPEG2 cf Onglet Num MPEG4 MPEG4 MPEG4 MPEG4 MPEG4 MPEG4 MPEG4 MPEG4 MPEG4 cf Onglet Num MPEG2-BXL ONLY MPEG2-BXL ONLY cf Onglet Num AB3 AB3 AB3 AB3 AB3 AB3 AB3 AB3 AB3 Analogique AB4 AB4 AB4 AB4 AB4 AB4 AB4 AB4 AB4 Analogique Barker VOO Barker VOO Barker VOO Barker VOO Barker VOO Barker VOO Barker VOO Barker VOO Barker VOO Analogique BBC 1 BBC 1 BBC 1 BBC 1 BBC 1 BBC 1 BBC 1 BBC 1 BBC 1 Analogique BBC 2 BBC 2 BBC 2 BBC 2 BBC 2 BBC 2 BBC 2 BBC 2 BBC 2 Analogique BBC World BBC World Bel ARTE / France 5 Bel ARTE / France 5 Bel ARTE / France 5 Bel ARTE / France 5 BBC World BBC World Bel ARTE / France 5 Analogique Bel ARTE / France 5 Bel ARTE / France 5 Canal Z Canal Z Canal Z Canal Z Bel ARTE / France 5 Bel ARTE / France 5 Bel ARTE / France 5 Analogique Canal Z Canal Z CANVAS CANVAS CANVAS CANVAS Canal Z Canal Z Canal Z Analogique CANVAS CANVAS Club RTL Club RTL Club RTL Club RTL CANVAS CANVAS CANVAS Analogique Club RTL Club RTL CNN CNN CNN CNN Club RTL Club RTL Club RTL Analogique CNN CNN Een Een Een Een CNN CNN CNN Analogique Een Een ERT ERT ERT ERT Een Een Een Analogique ERT ERT Euronews Euronews Euronews Euronews Euronews Euronews Euronews Analogique Euronews Euronews France 2 France 2 France 2 France 2 France 2 France 2 France 2 Analogique France 2 France 2 France 3 France 3 France 3 France 3 France 3 France 3 France 3 Analogique France 3 France 3 La Deux La Deux -

C72f99e6-0E06-4C50-A755-473Aab0b2680 Worldreginfo - C72f99e6-0E06-4C50-A755-473Aab0b2680 Key Figures 2008 – 2012

WorldReginfo - c72f99e6-0e06-4c50-a755-473aab0b2680 WorldReginfo - c72f99e6-0e06-4c50-a755-473aab0b2680 Key Figures 2008 – 2012 shAre PriCe PerFormanCe 2008 – 2012 – 6.5 % (2012: – 1.9 %) INDEX = 100 rTl group dJ sToXX – 16.1 % (2012: + 17.5 %) r evenue (€ million) e quiTy (€ million) 12 5,998 12 4,858 11 5,765 11 5,093 10 5,532 10 5,597 09 5,156 09 5,530 08 5,774 08 5,871 e BiTA (€ million) M ArKeT Capitalisation (€ billion)* 12 1,078 12 11.7 11 1,134 11 11.9 10 1,132 10 11.9 09 796 09 7.3 08 916 08 6.6 *Asof31December n eT ProFiT AttriButaBle To rTl grouP shAreholders (€ million) To tal dividend Per shAre (€ ) 12 597 12 10.50 11 696 11 5.10 10 611 10 5.00 09 205 09 3.50 08 194 08 3.50 Dividend payout 2008− 2012: € 4.2 billion WorldReginfo - c72f99e6-0e06-4c50-a755-473aab0b2680 2012 A nnuAl rePorT T he leAding euro PeAn en TerTAinMenT n eTworK WorldReginfo - c72f99e6-0e06-4c50-a755-473aab0b2680 RTL Television’s AlarmfürCobra11, Germany’s most popular action series, has become a hit format in some 140 countries around the globe. Since 2012, it has been one of the signature series of the newly launched action channel, Big RTL Thrill, in India WorldReginfo - c72f99e6-0e06-4c50-a755-473aab0b2680 ConTenTs Corporate information 6 Chairman’s statement 8 Chief executives’ report 14 Profit centres at a glance 16 The year in review 16 Broadcast 34 Content 60 Digital 72 Red Carpet 76 Corporate responsibility 92 Operations 94 How we work 96 The Board / executive Committee Financial information 104 directors’ report 110 Mediengruppe RTL Deutschland 114 Groupe M6 117 FremantleMedia 120 RTL Nederland 123 RTL Belgium 126 RTL Radio (France) 128 Other segments 143 Management responsibility statement 144 Consolidated financial statements 149 Notes 210 Auditors’ report 212 RTl group overview 214 Credits 215 Fully consolidated profit centres at a glance 217 Five-year summary WorldReginfo - c72f99e6-0e06-4c50-a755-473aab0b2680 irman’s ChA enT stateM Thomas rabe ChairmaN of The board of DiRectors In 2012, RTL Group delivered solid financial results. -

Liste Des Programmes Luxembourgeois

Services de télévision sur antenne soumis au contrôle de l’ALIA Dernière mise à jour : mars 2021 Services radiodiffusés à rayonnement international Nom du service Fournisseur de service RTL TVi RTL Belux s.a. & cie s.e.c.s. Club RTL 43, boulevard Pierre Frieden L-1543 Luxembourg Plug RTL RTL 4 Teleshop 4 RTL 5 Teleshop 5 RTL 7 Teleshop 7 RTL 8 Teleshop 8 RTL Telekids CLT-Ufa s.a. RTL Lounge 43, boulevard Pierre Frieden L-1543 Luxembourg RTL Crime RTL Z Film+ RTL II RTL+ RTL Gold Sorozat Musika TV Cool Page 1 sur 19 Service radiodiffusé visant le public résidant Nom du service Fournisseur de service RTL Télé Lëtzebuerg CLT-Ufa s.a. 43, boulevard Pierre Frieden 2ten RTL Télé Lëtzebuerg L-1543 Luxembourg Services luxembourgeois par satellite Nom du service Fournisseur de service Nordliicht a.s.b.l. Nordliicht 22, route de Diekirch L-9381 Moestroff Uelzechtkanal a.s.b.l. c/o Lycée de garçons Esch Uelzechtkanal 71, rue du Fossé L-4123 Esch/Alzette Dok TV s.a. .dok den oppene kanal 36, rue de Kopstal L-8284 Kehlen Luxembourg Movie Production a.s.b.l. Kanal 3 5, rue des Jardins L-7325 Heisdorf Osmose Media s.a. Euro D 177, rue de Luxembourg L-8077 Bertrange Luxe.TV (HD) (version anglaise) Luxe.TV (HD) (version française) Opuntia s.a. Luxe.TV Luxembourg (UHD 4K) 45, rue Siggy vu Lëtzebuerg (version anglaise) L-1933 Luxembourg Luxe TV Luxembourg (UHD 4K) (version française) Goto Luxe.TV (SD) (version anglaise) N 1 (version croate) N 1 (version bosnienne) Adria News s.à r.l. -

&\Brking Documenats

Eunopean Comnmunities EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT &\brking Documenats 1.981 ].982 23 FEBRUARY 1982 DOCUMENT I-IOI3/81 REPORT DRAWN I]P ()N BEIIALF OIT 'l'llE Cornmit-tee on Youth, CuI ture, Education, 1 nformation and Sport on radio and television broadcasting 1n thc European Community Rapporteur: MT W. IIAIIN i:nglish ljdition Pll 7 ).271/'f in. At its sitting oi- 19 September 1980, tlre European Pqrl lanl(.:nL referred to the Comrnittee on Youth, Culture, EducaLron, Information and Sport as the eommittee responsible and to the Committee on Budgets, the Political Affairs Committee and the Legal Affarrs Committee for their opinion, the motion for a resofution tabled by Mr PEDII*II,, Mr IIAHN and others on 'radio and television broadcasting in the European Community' (Doc. L-4O9/80), and the motion for a reeolution tabled by Ivlr SCHINZEL and others on rthe threat to diversity of opinion posed by commercial- j, isarion of new me<1ial(Doc. ]--4t'?/t)o). The ConuniLtce on BudqeLs srrbse,{rreht:Iy communicated its decision not I o drafL an opinion at thi.s stage. The commj.ttee declded that, although 'the subit'r:Ls rrf thr' t.vl() m(,i jr)r.:) for resolutj.on overlatrped in certain respecEs whi.clr might -c,1 rire cros$- references, they differed sufficientLy to warrant the preparatit-rn of two separate reports At its meeting of 22 october 1980, tlre Committee on Youth, Culture, Education, lnformation and Sport appointed Mr HAUN rapporteur onrradio and television broadeasting ir, the European Community'. The committee considered the motion for a resolution at its meetings of 23-24 September I98l and 10-Il Novem!'rer I'r8I. -

Crime for Everyone Launching the Digital Channel RTL Crime, RTL Nederland Creates a New Brand for Those Who Love the Thrill

1 September 2011 week 35 Crime for everyone Launching the digital channel RTL Crime, RTL Nederland creates a new brand for those who love the thrill Germany Netherlands IP Deutschland introduces RTL Nederland presents a common ‘convergence’ currency new season line-up France Belgium M6 and CBS Studios International Consistency is the key word extend partnership for the new season the RTL Group intranet week 35 Cover: Montage with RTL Crime’s TV programmes such as CSI and 24 2 the RTL Group intranet week 35 Thrills by the score Dutch crime lovers have a reason to cheer, when RTL Nederland launches its second digital channel. Nicolas Eglau explains how RTL Crime takes viewers into custody. The RTL Crime logo was designed bright and friendly The Netherlands - 1 September 2011 Starting 1 September, RTL Nederland watch crime series like the CSI franchise.” The extends its family of channels with a second RTL Crime channel design reflects this insight. digital thematic channel: RTL Crime. The new Nicolas Eglau says “its logo and optics are channel offers the best of domestic and US brighter and more friendly than one would expect crime series as well as documentaries on true from a crime-themed channel, as we target both stories behind high-profile criminal cases. women and men.” Nicolas Eglau, Director RTL Ventures, explains: “RTL Crime gives all fans of crime stories an alibi. We are expanding our range of digital broadcasts by launching a new channel that fits perfectly into our existing family. We are launching RTL Crime not just as an entertainment channel, but as a new brand for all crime story fans”. -

Full-Year Results 2020

FULL-YEAR RESULTS 2020 ENTERTAIN. INFORM. ENGAGE. KEY FIGURES +18.01 % SDAX +8.77 % MDAX SHARE PERFORMANCE 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2020 in per cent INDEX = 100 -7.65 % SXMP -9.37 % RTL GROUP -1.11 % PROSIEBENSAT1 RTL Group share price development for January to December 2020 based on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange (Xetra) against MDAX/SDAX, Euro Stoxx 600 Media and ProSiebenSat1 RTL GROUP REVENUE SPLIT 8.5 % OTHER 17.5 % DIGITAL 43.8 % TV ADVERTISING 20.0 % CONTENT 6.7 % 3.5 % PLATFORM REVENUE RADIO ADVERTISING RTL Group’s revenue is well diversified, with 43.8 per cent from TV advertising, 20.0 per cent from content, 17.5 per cent from digital activities, 6.7 per cent from platform revenue, 3.5 per cent from radio advertising, and 8.5 per cent from other revenue. 2 RTL Group Full-year results 2020 REVENUE 2016 – 2020 (€ million) ADJUSTED EBITA 2016 – 2020 (€ million) 20 6,017 20 853 19 6,651 19 1,156 18 6,505 18 1,171 17 6,373 17 1,248 16 6,237 16 1,205 PROFIT FOR THE YEAR 2016 – 2020 (€ million) EQUITY 2016 – 2020 (€ million) 20 625 20 4,353 19 864 19 3,825 18 785 18 3,553 17 837 17 3,432 16 816 16 3,552 MARKET CAPITALISATION* 2016 – 2020 (€ billion) TOTAL DIVIDEND/DIVIDEND YIELD PER SHARE 2016 – 2020 (€ ) (%) 20 6.2 20 3.00 8.9 19 6.8 19 NIL* – 18 7.2 18 4.00** 6.3 17 10.4 17 4.00*** 5.9 16 10.7 16 4.00**** 5.4 *As of 31 December *On 2 April 2020, RTL Group’s Board of Directors decided to withdraw its earlier proposal of a € 4.00 per share dividend in respect of the fiscal year 2019, due to the coronavirus outbreak ** Including