Pulling Together in a Crisis? Anarchism,Feminism and the Limits of Left-Wing Convergence in Austerity Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stuart Hall and Feminism: Revisiting Relations Stuart Hall E Feminismo: Revisitando Relações

61 Stuart Hall and Feminism: revisiting relations Stuart Hall e feminismo: revisitando relações ANA CAROLINA D. ESCOSTEGUY* Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Graduate Program in Communications. Porto Alegre – RS, Brazil ABSTRACT This article firstly addresses Stuart Hall’s account of the contributions of feminism to * PhD in Communication Sciences from the the formation of cultural studies. Secondly, it deals with the development of feminist University of São Paulo, criticism in the context of cultural studies, especially in England. Following this line, Professor at Pontifical Catholic University of Rio it retrieves Hall’s ideas on the problematic of identity(ies). This dimension of his work Grande do Sul and CNPq is the third approach to be explored, a subject also relevant in feminist theoretical pro- Researcher. Author of Cartografias dos estudos duction. The paper additionally points out matches and mismatches of such develop- culturais: uma versão ments in the Brazilian context. Finally, it concludes that the theme deserves in-depth latino-americana (Belo Horizonte: analysis, especially as the topic of identity plays a central role in current political prac- Autêntica, 2002). tice and feminist theory. Orcid: http://orcid. org/0000-0002-0361-6404 Keywords: Estudos culturais, Stuart Hall, feminismo, identidade E-mail: [email protected] RESUMO Este artigo aborda, em primeiro lugar, a narrativa de Stuart Hall sobre as contribuições do feminismo para a formação dos estudos culturais. Em segundo, trata do desen- volvimento da crítica feminista no âmbito dos estudos culturais, sobretudo ingleses. Nessa trajetória, resgata as ideias de Hall sobre a problemática da(s) identidade(s). -

Stop the War: the Story of Britain’S Biggest Mass Movement by Andrew Murray and Lindsey German, Bookmarks, 2005, 280 Pp

Stop the War: The Story of Britain’s Biggest Mass Movement by Andrew Murray and Lindsey German, Bookmarks, 2005, 280 pp. Abdullah Muhsin and Gary Kent I am sorry. If you think I am going to sit back and agree with beheadings, kidnappings, torture and brutality, and outright terrorization of ordinary Iraqi and others, then you can forget it. I will not be involved whatsoever, to me it is akin to supporting the same brutality and oppression inflicted on Iraq by Saddam, and the invading and occupying forces of the USA. Mick Rix, former left-wing leader of the train drivers’ union, ASLEF, writing to Andrew Murray to resign from the Stop the War Coalition. Andrew Murray and Lindsey German are, respectively, the Chair and Convenor of the Stop the War Coalition. Their book tells a story about a ‘remarkable mass movement’ which the authors hope ‘can change the face of politics for a generation.’ It tracks the Coalition from its origins with no office, no bank account, just one full time volunteer, through the ‘chaos of its early meetings’ to the million-strong demonstration of February 2003. The book seeks to explain the Coalition’s success in bringing together the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and ‘the Muslim Community’ to create ‘the broadest basis ever seen for a left-led movement.’ The authors attack the ‘imperialist’ doctrines of George Bush and Tony Blair, criticise the arguments of the ‘pro-war left,’ and finish with a chapter opposing the occupation and demanding immediate troop withdrawal. In addition, the book includes a broad -

CHAPTER VI Individualism and Futurism: Compagni in Milan

I Belong Only to Myself: The Life and Writings of Leda Rafanelli Excerpt from: CHAPTER VI Individualism and Futurism: Compagni in Milan ...Tracking back a few years, Leda and her beau Giuseppe Monanni had been invited to Milan in 1908 in order to take over the editorship of the newspaper The Human Protest (La Protesta Umana) by its directors, Ettore Molinari and Nella Giacomelli. The anarchist newspaper with the largest circulation at that time, The Human Protest was published from 1906–1909 and emphasized individual action and rebellion against institutions, going so far as to print articles encouraging readers to occupy the Duomo, Milan’s central cathedral.3 Hence it was no surprise that The Human Protest was subject to repeated seizures and the condemnations of its editorial managers, the latest of whom—Massimo Rocca (aka Libero Tancredi), Giovanni Gavilli, and Paolo Schicchi—were having a hard time getting along. Due to a lack of funding, editorial activity for The Human Protest was indefinitely suspended almost as soon as Leda arrived in Milan. She nevertheless became close friends with Nella Giacomelli (1873– 1949). Giacomelli had started out as a socialist activist while working as a teacher in the 1890s, but stepped back from political involvement after a failed suicide attempt in 1898, presumably over an unhappy love affair.4 She then moved to Milan where she met her partner, Ettore Molinari, and turned towards the anarchist movement. Her skepticism, or perhaps burnout, over the ability of humans to foster social change was extended to the anarchist movement, which she later claimed “creates rebels but doesn’t make anarchists.”5 Yet she continued on with her literary initiatives and support of libertarian causes all the same. -

Assessing the Progress of Gender Parity in Education Through Achieving Millennium Development Goals: a Case Study of Quetta District Balochistan

Bulletin of Education and Research December 2012, Vol. 34, No. 2 pp.47-58 Assessing the progress of Gender Parity in Education through achieving Millennium Development Goals: A case Study of Quetta District Balochistan Abdul Rashid, Dr. Zainab Bibi & Siraj ud din _______________________________________________________________ Abstract Using secondary data of Government Schools and literacy department for 10 years that is 2000-2010, this paper assesses the progress on the issue of gender equality within the framework of education related Millennium Development Goals (MDG) in district Quetta. The assessment is based on the selected indicators of goals by applying descriptive statistical tools such as ratio, mean and fixed chain methods. The major findings include; (a) the overall trend reveals positive change; (b) the pace of adult education is more biased against women; (c) the targets of literacy rate of children with 10+ years will hopefully be achieved; (d) the indicator to remove gender disparity related to net primary enrolment ratio will hopefully, be achieved; (e) the target of NER (Net enrollment ratio) will, perhaps not be achieved due to high drop out; (f) empowerment of woman through employment show bleak picture. The implications of findings for plan of action include: shifting more resources to primary education; creating more institutions for girls’ education especially in the rural areas; strengthening institutional capacity of government sector and creating more jobs opportunities for women in the public sector Key Words: Gender parity, millennium development goals, empowerment and positive discrimination and policy implications. _______________________________________________________________ Assessing the progress of Gender Parity in Education 48 Introduction Millennium development goals (MDGs) are defined as an agenda of development conceived in terms of measurable quantitative indicators. -

Barbara Erenreich, “What Is Socialist Feminism?”

You are a woman in a capitalist society. For good reasons, then, women are You get pissed off: about the job, about the considering whether or not “socialist bills, about your husband (or ex), about the feminism” makes sense as a political theory. kids’ school, the housework, being pretty, For socialist feminists do seem to be both not being pretty, being looked at, not being sensible and radical—at least, most of them looked at (and either way, not listened to), evidently feel a strong antipathy to some of etc. If you think about all these things and the reformist and solipsistic traps into which how they fit together and what has to be increasing numbers of women seem to be changed, and then you look around for some stumbling. words to hold all these thoughts together in To many of us more unromantic types, the abbreviated form, you almost have to come Amazon Nation, with its armies of strong- up with ‘socialist feminism.’ limbed matriarchs riding into the sunset, (Barbara Erenreich, “What is Socialist is unreal, but harmless. A more serious Feminism?”) matter is the current obsession with the Great Goddess and assorted other objects From all indications a great many women of worship, witchcraft, magic, and psychic have “come up” with socialist feminism phenomena. As a feminist concerned with as the solution to the persistent problem transforming the structure of society, I find of sexism. “Socialism” (in its astonishing this anything but harmless. variety of forms) is popular with a lot of Item One: Over fourteen hundred women people these days, because it has much to went to Boston in April, 1976 to attend a offer: concern for working people, a body of women’s spirituality conference dealing in revolutionary theory that people can point to large part with the above matters. -

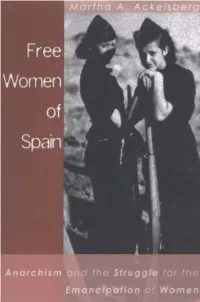

Ackelsberg L

• • I I Free Women of Spain Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women I Martha A. Ackelsberg l I f I I .. AK PRESS Oakland I West Virginia I Edinburgh • Ackelsberg. Martha A. Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women Lihrary of Congress Control Numher 2003113040 ISBN 1-902593-96-0 Published hy AK Press. Reprinted hy Pcrmi"inn of the Indiana University Press Copyright 1991 and 2005 by Martha A. Ackelsherg All rights reserved Printed in Canada AK Press 674-A 23rd Street Oakland, CA 94612-1163 USA (510) 208-1700 www.akpress.org [email protected] AK Press U.K. PO Box 12766 Edinburgh. EH8 9YE Scotland (0131) 555-5165 www.akuk.com [email protected] The addresses above would be delighted to provide you with the latest complete AK catalog, featur ing several thousand books, pamphlets, zines, audio products, videos. and stylish apparel published and distributed bv AK Press. A1tern�tiv�l�! Uil;:1t r\llr "-""'l:-,:,i!'?� f2":' �!:::: :::::;:;.p!.::.;: ..::.:.:..-..!vo' :uh.. ,.",i. IIt;W� and updates, events and secure ordering. Cover design and layout by Nicole Pajor A las compafieras de M ujeres Libres, en solidaridad La lucha continua Puiio ell alto mujeres de Iberia Fists upraised, women of Iheria hacia horiz,ontes prePiados de luz toward horizons pregnant with light por rutas ardientes, on paths afire los pies en fa tierra feet on the ground La frente en La azul. face to the blue sky Atirmondo promesas de vida Affimling the promise of life desafiamos La tradicion we defy tradition modelemos la arcilla caliente we moLd the warm clay de un mundo que nace del doLor. -

First Published 2018 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA Copyright © Max Haiven 2018 the Right Of

PROOF – Property of Pluto Press – not for unauthorised use TOC Art After Money, Money After Art: Introduction Max Haiven Creative Strategies Against Financialization Index First published 2018 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Max Haiven 2018 The right of Max Haiven to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3825 5 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3824 8 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7868 0318 4 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0320 7 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0319 1 EPUB eBook Published in Canada 2018 by Between the Lines 401 Richmond Street West, Studio 281, Toronto, Ontario, M5V 3A8 www.btlbooks.com Cataloguing in Publication information available from Library and Archives Canada ISBN 978 1 77113 398 2 Paperback ISBN 978 1 77113 400 2 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 77113 399 9 EPUB eBook This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Printedsample in Europe All images in this book remain the copyright of the artist unless otherwise stated. Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. -

Social Ecology and Communalism

Murray Bookchin Bookchin Murray $ 12,95 / £ xx,xx Social Ecology and Communalism Replace this text Murray Bookchin ocial cology Social Ecology and Communalism and Communalism Social Ecology S E and Communalism AK Press Social Ecology and Communalism Murray Bookchin Social Ecology and Communalism Bookchin, Murray Social Ecology and Communalism Library of Congress Control Number 2006933557 ISBN 978-1-904859-49-9 Published by AK Press © Eirik Eiglad and Murray Bookchin 2006 AK Press 674–A 23rd St. Oakland, CA 94612 USA www.akpress.org [email protected] AK Press UK PO Box 12766 Edinburgh, EH8 9YE Scotland (0131) 555–5165 www.akuk.com [email protected] Design and layout by Eirik Eiglad Contents An Introduction to Social Ecology and Communalism 7 What is Social Ecology? 19 Radical Politics in an Era of Advanced Capitalism 53 The Role of Social Ecology in a Period of Reaction 68 The Communalist Project 77 After Murray Bookchin 117 An Introduction to Social Ecology and Communalism We are standing at a crucial crossroads. Not only does the age- old “social question” concerning the exploitation of human labor remain unresolved, but the plundering of natural resources has reached a point where humanity is also forced to politically deal with an “ecological question.” Today, we have to make conscious choices about what direction society should take, to properly meet these challenges. At the same time, we see that our very ability to make the necessary choices are being undermined by an incessant centralization of economic and political power. Not only is there a process of centralization in most modern nation states that divests humanity of any control over social affairs, but power is also gradually being transferred to transnational institutions. -

A Socialist Schism

A Socialist Schism: British socialists' reaction to the downfall of Milošević by Andrew Michael William Cragg Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Marsha Siefert Second Reader: Professor Vladimir Petrović CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2017 Copyright notice Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection i Abstract This work charts the contemporary history of the socialist press in Britain, investigating its coverage of world events in the aftermath of the fall of state socialism. In order to do this, two case studies are considered: firstly, the seventy-eight day NATO bombing campaign over the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1999, and secondly, the overthrow of Slobodan Milošević in October of 2000. The British socialist press analysis is focused on the Morning Star, the only English-language socialist daily newspaper in the world, and the multiple publications affiliated to minor British socialist parties such as the Socialist Workers’ Party and the Communist Party of Great Britain (Provisional Central Committee). The thesis outlines a broad history of the British socialist movement and its media, before moving on to consider the case studies in detail. -

Islamic Feminism: a Discourse of Gender Justice and Equality

Linfield University DigitalCommons@Linfield Senior Theses Student Scholarship & Creative Works 5-27-2014 Islamic Feminism: A Discourse of Gender Justice and Equality Breanna Ribeiro Linfield College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/relsstud_theses Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Ribeiro, Breanna, "Islamic Feminism: A Discourse of Gender Justice and Equality" (2014). Senior Theses. 1. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/relsstud_theses/1 This Thesis (Open Access) is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It is brought to you for free via open access, courtesy of DigitalCommons@Linfield, with permission from the rights-holder(s). Your use of this Thesis (Open Access) must comply with the Terms of Use for material posted in DigitalCommons@Linfield, or with other stated terms (such as a Creative Commons license) indicated in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, or if you have questions about permitted uses, please contact [email protected]. Islamic Feminism: A Discourse of Gender Justice and Equality Breanna Ribeiro Senior Thesis for Religious Studies Major Advisor Bill Millar May 27, 2014 THESIS COPYRIGHT PERMISSIONS Please read this document carefully before sign1ng. If you have questions about any of these permissions, please contact the D1g1taiCommons Coordinator. Title of the Thesis: h!Amir.. fcMi>'liSv\1; A; Dike>JC"l. J'~ J!.M\o.. <Wi ~f'141if- Author's Name: (Last name, first name) 1Zhelrn1 b•UU'lllt>... Advisor's Name DigitaiCommons@Linfield is our web-based, open access-compliant institutional repository tor dig1tal content produced by Linfield faculty, students. -

The Feminist Fourth Wave

Conclusion The history of the wave is a` troubled one, even while it might seem to describe surges of feminist activism very accurately. It has led to progress and loss narratives emerging, both of which are used to justify tension and divisions between different generations of the social move- ment. The attention received by the multiple waves has also resulted in certain time periods being considered as ‘outside’ or ‘inactive’. Understanding feminism as divided into four wave moments of notable action, implies that the politics lapses into inaction between the surges. This, of course, is not the case, but our understanding of the wave ensures that ongoing and long-term activism are effaced from our overall understanding of the social movement. Waves have also come to be associated with specific figureheads and identities. The second and third wave are crudely characterised as earnest, consciousness-raising, and then DIY zine and punk cultures, respectively. The surge in activist intensity in those times ensures that specific women are positioned as representa- tive of the wave as a whole. The women, unfortunately, are often not reflective of the diversity actually occurring within the wave itself, making the narrative appear to be entirely tied to white feminism, as opposed to a more multicultural and intersectional social movement. It © The Author(s) 2017 185 P. Chamberlain, The Feminist Fourth Wave, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-53682-8 186 Conclusion is no surprise then, that the wave has been widely critiqued, and in some cases, wholly rejected in relation to a historical understanding of feminism. -

Reclaiming Lilith As a Strong Female Role Model

Linfield University DigitalCommons@Linfield Senior Theses Student Scholarship & Creative Works 5-29-2020 Reclaiming Lilith as a Strong Female Role Model Kendra LeVine Linfield College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/relsstud_theses Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation LeVine, Kendra, "Reclaiming Lilith as a Strong Female Role Model" (2020). Senior Theses. 5. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/relsstud_theses/5 This Thesis (Open Access) is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It is brought to you for free via open access, courtesy of DigitalCommons@Linfield, with permission from the rights-holder(s). Your use of this Thesis (Open Access) must comply with the Terms of Use for material posted in DigitalCommons@Linfield, or with other stated terms (such as a Creative Commons license) indicated in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, or if you have questions about permitted uses, please contact [email protected]. Reclaiming Lilith as a Strong Female Role Model Kendra LeVine RELS ‘20 5/29/20 A thesis submitted to the Department of Religious Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts in Religious Studies Linfield College McMinnville, Oregon THESIS COPYRIGHT PERMISSIONS Please read this document carefully before signing. If you have questions about any of these permissions, please contact the DigitalCommons Coordinator. Title of the Thesis: _____________________________________________________________ Author’s Name: (Last name, first name) _____________________________________________________________ Advisor’s Name _____________________________________________________________ DigitalCommons@Linfield (DC@L) is our web-based, open access-compliant institutional repository for digital content produced by Linfield faculty, students, staff, and their collaborators.