Black Feminism Reimagined After Intersectionality Jennifer C. Nash

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Intersectional Feminist Approach

GUIDING PRINCIPLE 1 AN INTERSECTIONAL FEMINIST APPROACH An intersectional approach to feminism acknowledges that while women share similar experiences of discrimination, harassment, sexism, inequality and oppression on the basis of their sex and gender, not all women are equally disadvantaged or have equal access to resources, power and privilege. An intersectional approach to feminism requires analysis and action that is not only gendered, but considers how other forms of systemic oppression and discrimination – such as racism, homophobia, transphobia, biphobia or ableism – can intersect with and impact on women’s experiences of gender, inequality, discrimination, harassment, violence or abuse. In the context of addressing violence against women, an intersectional approach recognises that the way women experience gender and inequality can be different based on a range of other cultural, individual, historical, environmental or structural factors including (but not limited to) race, age, geographic location, sexual orientation, ability or class. This approach also recognises that the drivers, dynamics and impacts of violence women experience can be compounded and magnified by their experience of other forms of oppression and inequality, resulting in some groups of women experiencing higher rates and/or more severe forms of violence, or facing barriers to support and safety that other women do not experience. DVRCV stands in solidarity with and supports work that addresses other forms of discrimination and oppression. We actively promote and give voice to this work and support those leading it to consider gender in their approach, just as we consider how our work to address violence against women can challenge other forms of oppression that women experience. -

The Variety of Feminisms and Their Contribution to Gender Equality

JUDITH LORBER The Variety of Feminisms and their Contribution to Gender Equality Introduction My focus is the continuities and discontinuities in recent feminist ideas and perspectives. I am going to discuss the development of feminist theories as to the sources of gender inequality and its pervasiveness, and the different feminist political solutions and remedies based on these theories. I will be combining ideas from different feminist writers, and usually will not be talking about any specific writers. A list of readings can be found at the end. Each perspective has made important contributions to improving women's status, but each also has limitations. Feminist ideas of the past 35 years changed as the limitations of one set of ideas were critiqued and addressed by what was felt to be a better set of ideas about why women and men were so unequal. It has not been a clear progression by any means, because many of the debates went on at the same time. As a matter of fact, they are still going on. And because all of the feminist perspectives have insight into the problems of gender inequality, and all have come up with good strategies for remedying these problems, all the feminisms are still very much with us. Thus, there are continuities and convergences, as well as sharp debates, among the different feminisms. Any one feminist may incorporate ideas from several perspec- tives, and many feminists have shifted their perspectives over the years. I myself was originally a liberal feminist, then a so- 8 JUDITH LORBER cialist feminist, and now consider myself to be primarily a so- cial construction feminist, with overtones of postmodernism and queer theory. -

Gendering (Bi)Sexuality by Laura Honsig

EHJVolume IX: Issue IISpring 2017 Gendering (Bi)Sexuality ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Laura Honsig In the United States we often associate the decade of the 1960’s with “free love” and radically liberated notions of gender and sexuality. Yet fascinating discussions around gender and sexuality were also happening in the early- and mid- 1970’s, ones that illuminate not only the evolution of movements and ideas during these decades, but also our own historical moment. This paper, which relies on primary sources, situates questions of sexual object choice, gender non-conformity, racialization, and “bisexuality” in the historical moment(s) of the 1970’s. These histories also have important connections to the contemporary moment of LGBT identities. I argue that today both bisexuality and transgender, while certainly acknowledged as labels that fit with lesbian and gay in a certain sense, are treated discursively and materially differently than the latter two, so often violently. For this reason, the last section of my paper draws connections between the 1970’s and the present. The decade of the 1970’s provides important perspectives for understanding how the currents of this earlier -

13 White Woman Listen! Black Feminism and the Boundaries of Sisterhood

13 White Woman Listen! Black Feminism and the Boundaries of Sisterhood Hazel V. Carby I'm leaving evidence. And you got to leave evidence too. And your children got to leave evidence.... They burned all the documents.... We got to burn out what they put in our minds, like you burn out a wound. Except we got to keep what we need to bear witness. That scar that's left to bear witness. We got to keep it as visible as our blood. (Jones 1975) The black women's critique of history has not only involved us in coming to terms with "absences"; we have also been outraged by the ways in which it has made us visible, when it has chosen to see us. History has constructed our sexuality and our femininity as deviating from those qualities with which white women, as the prize objects of the Western world, have been endowed. We have also been defined in less than human terms (Jordon 1969). Our continuing struggle with History began with its "discovery" of us. However, this chapter will be concerned with herstory rather than history. We wish to address questions to the feminist theories that have been developed during the last decade; a decade in which black women have been fighting, in the streets, in the schools, through the courts, inside and outside the wage relation. The significance of these struggles ought to inform the writing of the herstory of women in Britain. It is fundamental to the development of a feminist theory and practice that is meaningful for black women. -

Womanism: the Fight for Social Equality

University of Washington Tacoma UW Tacoma Digital Commons Gender & Sexuality Studies Student Work Collection School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Spring 6-2-2020 Womanism: The Fight for Social Equality Demetria Hawkins [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/gender_studies Recommended Citation Hawkins, Demetria, "Womanism: The Fight for Social Equality" (2020). Gender & Sexuality Studies Student Work Collection. 58. https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/gender_studies/58 This Undergraduate Zine is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences at UW Tacoma Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gender & Sexuality Studies Student Work Collection by an authorized administrator of UW Tacoma Digital Commons. Z I N E P R O J E C T WOMANISM: The Fight for Social Equality Presented by Demetria Hawkins -What is Womanism? -Womanism vs. Feminism -Gender/ Racial Discrimination in the Content Summary Work Place -Quality of Life: Men vs. Women DISCUSSION OVERVIEW -What does this all mean? MERRIAM- WEBSTER DEFINITION What is "A form of feminism focused especially on the conditions and concerns of black women." WOMANISM? THOUGHT CO. DEFINITION BY LINDA NAPIKOSKI "Identifies and critically analyzes sexism, black racism, and their intersection." ALICE WALKER DEFINITION "A [B]lack feminist or feminist of color," and "a woman who loves other women, sexually and/or non-sexually [...] committed to survival and wholeness of entire people, male and female." Alice Walker FOUNDER OF WOMANISM WHO IS SHE? Alice Walker is a known social activist, poet, novelist and known famously as the woman who coined the phrase Womanism. -

The Dialectic of Freedom 1St Edition Pdf Free Download

THE DIALECTIC OF FREEDOM 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Maxine Greene | 9780807728970 | | | | | The Dialectic of Freedom 1st edition PDF Book She examines the ways in which the disenfranchised have historically understood and acted on their freedom—or lack of it—in dealing with perceived and real obstacles to expression and empowerment. It offers readers a critical opportunity to reflect on our continuing ideological struggles by examining popular books that have made a difference in educational discourse. Professors: Request an Exam Copy. Major works. Max Horkheimer Theodor W. The latter democratically makes everyone equally into listeners, in order to expose them in authoritarian fashion to the same programs put out by different stations. American Paradox American Quest. Instead the conscious decision of the managing directors executes as results which are more obligatory than the blindest price-mechanisms the old law of value and hence the destiny of capitalism. Forgot your password? There have been two English translations: the first by John Cumming New York: Herder and Herder , ; and a more recent translation, based on the definitive text from Horkheimer's collected works, by Edmund Jephcott Stanford: Stanford University Press, Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. Peter Lang. The truth that they are nothing but business is used as an ideology to legitimize the trash they intentionally produce. Archetypal literary criticism New historicism Technocriticism. The author concludes with suggestions for approaches to teaching and learning that can provoke both educators and students to take initiatives, to transcend limits, and to pursue freedom—not in solitude, but in reciprocity with others, not in privacy, but in a public space. -

Citation Abstract

Citation # I.1 Wokabi, F.G. (?). Critical thinking triad as a model for enhancing the quality and relevance of higher education in Kenya. (Paper). Kenyatta University, Department of Philosophy, Nairobi, Kenya. 1-11. [PDF+] URL http://www.daad.de/de/download/alumni/veranstaltungen/06_11_06/Presented%20papers/Copy%20of%20Francis%20Gikonyo.pdf Abstract Introduction: The purpose of this paper is to show the significance of the Critical Thinking Triad in enhancing the quality and relevance of higher education in Kenya. In order to pursue this goal, it is necessary to clarify the key concepts that inform this paper namely: Education, Quality, Relevance, Critical Thinking, and Critical Thinking Triad. The analytical dimension of critical thinking involves identifying the fundamental structures or elements of any form of thinking. Thought comprises of parts namely: purposes, questions, points of view, information, inferences, concepts, implications, and assumptions. (Paul and Elder, 2001: 50). The evaluative dimension of critical thinking comprises of universal intellectual standards that are useful in assessing the quality of thought. They include: clarity, accuracy, precision, relevance, depth, breadth, logicalness, significance, and adequacy among others (Paul and Elder, 2002:98). Quotes -The conceptual framework that informs the paper is Paul and Elder’s (2002) conception of Critical Thinking. Referenced From Paul, R. 1995. Critical Thinking: How to Prepare Students for a Rapidly Changing World. California: Foundation for Critical Thinking. Paul, R. and Elder, L. 2001. Critical Thinking: Tools for Taking Charge of Your Learning and Your Life. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall. Paul, R. and Elder, L.2002. Critical Thinking: Tools for Taking Charge of Your Professional and Personal Life. -

JBSR 4.1.Indd

volume 4 number 1 summer 2017 Journal of Black Sexuality and Relationships james c. wadley, phd, editor Lincoln University jeanine staples, edd, guest editor Penn State University Copyright © 2018 James C. Wadley Th e Journal of Black Sexuality and Relationships (JBSR) is a refereed, interdisciplinary, scholarly inquiry devoted to addressing the epistemological, ontological, and social con- struction of sexual expression and relationships of persons within the African diaspora. Th e journal will be used as a medium to capture the functionality and dysfunctionality of individuals, couples, and families as well as the effi cacy in which relationships are nego- tiated. Th e journal seeks to take into account the transhistorical substrates that subsume behavioral, aff ective, and cognitive functioning of persons of African descent as well as those who educate or clinically serve this important population. For additional informa- tion about the JBSR, you can visit Th eJBSR .com, follow us on twitter @Th eJBSR, like our Facebook page, or review current JBSR trends on LinkedIn. Subscriptions Th e Journal of Black Sexuality and Relationships (ISSN 2334- 2668) is published quarterly by the University of Nebraska Press. For current subscription rates please see our website: www .nebraskapress .unl .edu. If ordering by mail, please make checks payable to the University of Nebraska Press and send to Th e University of Nebraska Press 1111 Lincoln Mall Lincoln, NE 68588- 0630 Telephone: 402- 472- 8536 submissions Manuscripts should be prepared in 12- point Times New Roman with 1- inch margins. Notes and apparatus must conform to the sixth edition of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association. -

Multiple Jeopardy in the Works of African American Writers and Maya Angelou P.Jayageetha#1, Dr.S.S

Journal of Interdisciplinary Cycle Research ISSN NO: 0022-1945 Multiple jeopardy in the works of African American writers and Maya Angelou P.Jayageetha#1, Dr.S.S. Jansirani*2. # Research Scholar, PG and Research Department of English, Government Arts College, Trichy, Tamilnadu-22. Abstract— The Twentieth century has been a period of intense literary activity for African American women writers. It was a time when for the first time these talented writers started to write and empress their creative genius, Maya Angelou and women writers started to express themselves truly for the first time. Their works portray their growth, struggle. African American women writers have given readers powerful insights into grim issues such as race, gender and class, but before one makes a deep inquiry into the works of these women writers, it is highly essential to know about their past. Keywords— Ieopardy, Racism, Classicism, Sexism, Pejorative. I. INTRODUCTION The twentieth century has been an epoch making era for the African American literary tradition because of the significant contributions made by African American women writers during this century. African American women writers such as Zora Neale Hurston, Ann Petry, Paule Marshall, Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Gloria Naylor and many others have rewritten the existing literary traditions by expressing themselves and creating a deep impact on the African American, literary arena. The works of these women writers reverberate with self-expression, thus achieving a canonical status and enriching not only African American but also the American literary world. These writers write not only about themselves, but also about African American women. -

Thinking Feminism Cross-Culturally

Thinking feminism cross-culturally -The tension between culture and gender equality- Frieda Pauline Reitzer (u894089) Honours Program: Discourses on Europe Prof: Paul Scheffer Tilburg University, Tilburg the 03.02.2018 One day after the Golden Globes took place with its visitors wearing all black, the BBC published an article which asked if now, Bollywood would follow Hollywood in that big step taken towards gender equality. The reaction of Bollywood-star Kalki Koechlin showed of the misconstruction of global feminism by the BBC: “it would just become a shocking headline”, “If you get touched in a bus, you don’t even think about it anymore” (BBC, 2018). The act of sexual abuse is a crime independent of place and time, the approach to fight it is not. “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.” - (Art 1, Universal declaration of Human Rights) Introduction Globalization entails an increase in cultural plurality that will confront Europe in the near future. Rising economies like India bring merely aspects of culture on the global stage which seem to contradict the norms of the European community. India is a country in which many women face the attack of their dignity in every sphere of life. Unpunished rapes, domestic violence, less chances for education and the patronization in essential decisions are just a few examples. The idea of women being subordinated by men is widespread and rooted in cultural beliefs and traditions. The question is, how should one take a position when women’s rights are systematically violated in the name of culture? How should the tension between the tolerance of cultural plurality and the universal demand for gender equality be balanced? And what are the political conditions when aiming at the global gender equality? The first part of the essay will explore the tensions between culture and gender equality. -

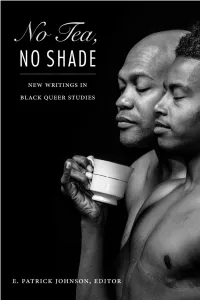

NO TEA, NO SHADE This Page Intentionally Left Blank No Tea, NO SHADE

NO TEA, NO SHADE This page intentionally left blank No Tea, NO SHADE New Writings in Black Queer Studies EDITED BY E. Patrick Johnson duke university press Durham & London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Adobe Caslon by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Johnson, E. Patrick, [date] editor. Title: No tea, no shade : new writings in Black queer studies / edited by E. Patrick Johnson. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016022047 (print) lccn 2016023801 (ebook) isbn 9780822362227 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362425 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373711 (e- book) Subjects: lcsh: African American gays. | Gay and lesbian studies. | African Americans in popu lar culture. | Gays in popu lar culture. | Gender identity— Political aspects. | Sex in popu lar culture. Classification: lcc e185.625.n59 2016 (print) | lcc e185.625 (ebook) | ddc 306.76/608996073— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2016022047 Cover art: Philip P. Thomas, Sharing Tea, 2016. © Philip P. Thomas. FOR ALL THE QUEER FOREMOTHERS AND FOREFATHERS This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS foreword Cathy J. Cohen xi acknowl edgments xv introduction E. Patrick Johnson 1 CHAPTER 1. Black/Queer Rhizomatics Train Up a Child in the Way Ze Should Grow . JAFARI S. ALLEN 27 CHAPTER 2. The Whiter the Bread, the Quicker You’re Dead Spectacular Absence and Post-Racialized Blackness in (White) Queer Theory ALISON REED 48 CHAPTER 3. Troubling the Waters Mobilizing a Trans* Analytic KAI M. -

Intersectional Invisibility (2008).Pdf

Sex Roles DOI 10.1007/s11199-008-9424-4 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Intersectional Invisibility: The Distinctive Advantages and Disadvantages of Multiple Subordinate-Group Identities Valerie Purdie-Vaughns & Richard P. Eibach # Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2008 Abstract The hypothesis that possessing multiple subordi- Without in any way underplaying the enormous nate-group identities renders a person “invisible” relative to problems that poor African American women face, I those with a single subordinate-group identity is developed. want to suggest that the burdens of African American We propose that androcentric, ethnocentric, and heterocentric men have always been oppressive, dispiriting, demor- ideologies will cause people who have multiple subordinate- alizing, and soul-killing, whereas those of women group identities to be defined as non-prototypical members of have always been at least partly generative, empower- their respective identity groups. Because people with multiple ing, and humanizing. (Patterson 1995 pp. 62–3) subordinate-group identities (e.g., ethnic minority woman) do not fit the prototypes of their respective identity groups (e.g., ethnic minorities, women), they will experience what we have Introduction termed “intersectional invisibility.” In this article, our model of intersectional invisibility is developed and evidence from The politics of research on the intersection of social historical narratives, cultural representations, interest-group identities based on race, gender, class, and sexuality can politics, and anti-discrimination legal frameworks is used to at times resemble a score-keeping contest between battle- illustrate its utility. Implications for social psychological weary warriors. The warriors display ever deeper and more theory and research are discussed. gruesome battle scars in a game of one-upmanship, with each trying to prove that he or she has suffered more than Keywords Intersectionality.