JBSR 4.1.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preventable Tragedies

Preventable Tragedies How to Reduce Mental Health-Related Deaths in Texas Jails The University of Texas School of Law Civil Rights Clinic This report does not represent the official position of The University of Texas School of Law or of The University of Texas. The views presented here reflect only the opinions of the individual authors and of the Civil Rights Clinic. Preventable Tragedies: How to Reduce Mental-Health Related Deaths in Texas Jails © The University of Texas School of Law Civil Rights Clinic November 2016 THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN SCHOOL OF LAW Civil Rights Clinic 727 East Dean Keeton Street Austin, Texas 78705 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 AUTHORS, METHODOLOGY AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 4 INTRODUCTION 5 I. PREVENTABLE TRAGEDIES: STORIES FROM FAMILIES 10 Terry Borum: Swisher County Jail, Feb. 2013 11 Gregory Cheek: Nueces County Jail, Feb. 2011 13 Amy Lynn Cowling: Gregg County Jail, Dec. 2010 15 Lacy Dawn Cuccaro: Hansford County Jail, July 2012 17 Eric Dykes: Hays County Jail, Mar. 2011 19 Victoria Gray: Brazoria County Jail, Sep. 2014 21 Jesse C. Jacobs: Galveston County Jail, Mar. 2015 23 Robert Montano: Orange County Jail, Oct. 2011 25 Robert Rowan: Smith County Jail, Nov. 2014 27 Chad Snell: Denton County Jail, Mar. 2015 29 The Tip of the Iceberg 31 Increasing Transparency After a Jail Death 32 Ensuring Independent Investigations of Deaths in Custody 32 Advocating for Inmates Across Texas: The Texas Jail Project 33 Texas Sheriffs Support Mental Health Reforms 34 Advancing Wellness: Perspective from Mental Health Advocates 35 II. PATHWAYS TO REFORM: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR POLICIES AND PRACTICE 36 No. -

Top 200 Most Requested Songs

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2013 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 2 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 3 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 4 Lmfao Sexy And I Know It 5 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 6 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 7 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 8 Psy Gangnam Style 9 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 10 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 11 B-52's Love Shack 12 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 13 Maroon 5 Feat. Christina Aguilera Moves Like Jagger 14 Jepsen, Carly Rae Call Me Maybe 15 V.I.C. Wobble 16 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 17 Beatles Twist And Shout 18 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 19 Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Feat. Wanz Thrift Shop 20 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 21 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 22 Lmfao Feat. Lauren Bennett And Goon Rock Party Rock Anthem 23 Pink Raise Your Glass 24 Outkast Hey Ya! 25 Isley Brothers Shout 26 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 27 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 28 Mars, Bruno Marry You 29 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 30 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 31 Lumineers Ho Hey 32 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 33 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 34 Sister Sledge We Are Family 35 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 36 Temptations My Girl 37 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 38 Train Marry Me 39 Kool & The Gang Celebration 40 Daft Punk Feat. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Anti-Racism Resources

Anti-Racism Resources Prepared for and by: The First Church in Oberlin United Church of Christ Part I: Statements Why Black Lives Matter: Statement of the United Church of Christ Our faith's teachings tell us that each person is created in the image of God (Genesis 1:27) and therefore has intrinsic worth and value. So why when Jesus proclaimed good news to the poor, release to the jailed, sight to the blind, and freedom to the oppressed (Luke 4:16-19) did he not mention the rich, the prison-owners, the sighted and the oppressors? What conclusion are we to draw from this? Doesn't Jesus care about all lives? Black lives matter. This is an obvious truth in light of God's love for all God's children. But this has not been the experience for many in the U.S. In recent years, young black males were 21 times more likely to be shot dead by police than their white counterparts. Black women in crisis are often met with deadly force. Transgender people of color face greatly elevated negative outcomes in every area of life. When Black lives are systemically devalued by society, our outrage justifiably insists that attention be focused on Black lives. When a church claims boldly "Black Lives Matter" at this moment, it chooses to show up intentionally against all given societal values of supremacy and superiority or common-sense complacency. By insisting on the intrinsic worth of all human beings, Jesus models for us how God loves justly, and how his disciples can love publicly in a world of inequality. -

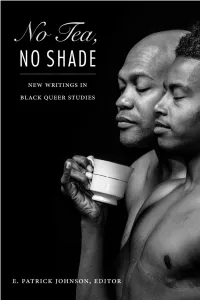

NO TEA, NO SHADE This Page Intentionally Left Blank No Tea, NO SHADE

NO TEA, NO SHADE This page intentionally left blank No Tea, NO SHADE New Writings in Black Queer Studies EDITED BY E. Patrick Johnson duke university press Durham & London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Adobe Caslon by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Johnson, E. Patrick, [date] editor. Title: No tea, no shade : new writings in Black queer studies / edited by E. Patrick Johnson. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016022047 (print) lccn 2016023801 (ebook) isbn 9780822362227 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362425 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373711 (e- book) Subjects: lcsh: African American gays. | Gay and lesbian studies. | African Americans in popu lar culture. | Gays in popu lar culture. | Gender identity— Political aspects. | Sex in popu lar culture. Classification: lcc e185.625.n59 2016 (print) | lcc e185.625 (ebook) | ddc 306.76/608996073— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2016022047 Cover art: Philip P. Thomas, Sharing Tea, 2016. © Philip P. Thomas. FOR ALL THE QUEER FOREMOTHERS AND FOREFATHERS This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS foreword Cathy J. Cohen xi acknowl edgments xv introduction E. Patrick Johnson 1 CHAPTER 1. Black/Queer Rhizomatics Train Up a Child in the Way Ze Should Grow . JAFARI S. ALLEN 27 CHAPTER 2. The Whiter the Bread, the Quicker You’re Dead Spectacular Absence and Post-Racialized Blackness in (White) Queer Theory ALISON REED 48 CHAPTER 3. Troubling the Waters Mobilizing a Trans* Analytic KAI M. -

Can You Predict a Hit?

CAN YOU PREDICT A HIT? FINDING POTENTIAL HIT SONGS THROUGH LAST.FM PREDICTORS BACHELOR THESIS MARVIN SMIT (0720798) DEPARTMENT OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE RADBOUD UNIVERSITEIT NIJMEGEN SUPERVISORS: DR. L.G. VUURPIJL DR. F. GROOTJEN Abstract In the field of Music Information Retrieval, studies on Hit Song Science are becoming more and more popular. The concept of predicting whether a song has the potential to become a hit song is an interesting challenge. This paper describes my research on how hit song predictors can be utilized to predict hit songs. Three subject groups of predictors were gathered from the Last.fm service, based on a selection of past hit songs from the record charts. By gathering new data from these predictors and using a term frequency-inversed document frequency algorithm on their listened tracks, I was able to determine which songs had the potential to become a hit song. The results showed that the predictors have a better sense on listening to potential hit songs in comparison to their corresponding control groups. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................... 1 2 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................ 2 2.1 MUSIC INFORMATION RETRIEVAL ................................................................................................. 2 2.2 HIT SONG SCIENCE ........................................................................................................................... -

Pour It up Rhiannon 3 Star Term 6 2019

Pour It Up – Rhiannon 3 STAR Term 6 2019 Chori by Sammy C Throw it up, throw it up Back to pole, right arm up left arm up Watch it all fall out Turn face the pole Pour it up, pour it up Candle legs That's how we ball out (ball out) Throw it up, throw it up Right arm up left arm up Watch it all fall out Pour it up, pour it up Candle legs That's how we ball out Strip clubs and dollar bills Pivot back to pole I still got my money clap legs together and open Patron shots. Can I get a refill? Left leg through right leg turn to face pole I still got my money Sit with pole between legs Strippers goin' up and down that Spin around 1 and half times to left pole side of pole And I still got my money Sit on left hip Four o'clock and we ain't going Lift right leg up home 'Cause I still got my money Roll over on tummy and to right hip Money make the world go round Fan lead with left leg I still got my money Turn onto tummy Bands make your girl go down Body roll down, lead with chest I still got my money Lift bum up Lot more where that came from Tap right to left I still got my money Slide up to knees The look in yo eyes I know you Stripper legs down want some I still got my money Oh oh oh Left leg lunge and right leg lunge All I see is signs Hip rolls All I see is dollar signs Hip roll and knees together Oh oh oh Bend and up, turn back to pole Money on my mind Hand up leg and fingers together Money, money on my mind Head roll Throw it, throw it up Turn to face pole Watch it fall off from the sky Climb head roll Throw it up, throw it up Star gazer -

Policing at the Nexus of Race and Mental Health Camille A

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 43 Number 3 Mental Health, the Law, & the Urban Article 4 Environment 2016 Frontlines: Policing at the Nexus of Race and Mental Health Camille A. Nelson Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Recommended Citation Camille A. Nelson, Frontlines: Policing at the Nexus of Race and Mental Health, 43 Fordham Urb. L.J. 615 (2016). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol43/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FRONTLINES: POLICING AT THE NEXUS OF RACE AND MENTAL HEALTH Camille A. Nelson* ABSTRACT The last several years have rendered issues at the intersection of race, mental health, and policing more acute. The frequency and violent, often lethal, nature of these incidents is forcing a national conversation about matters which many people would rather cast aside as volatile, controversial, or as simply irrelevant to conversations about the justice system. It seems that neither civil rights activists engaged in the work of advancing racial equality nor disability rights activists recognize the potent combination of negative racialization and mental illness at this nexus that bring policing practices into sharp focus. As such, the compounding dynamics and effects of racism, mental health, and policing remain underexplored and will be the foci of this Article. -

Top 200 Most Requested Songs

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2013 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 2 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 3 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 4 Lmfao Sexy And I Know It 5 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 6 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 7 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 8 Psy Gangnam Style 9 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 10 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 11 B-52's Love Shack 12 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 13 Maroon 5 Feat. Christina Aguilera Moves Like Jagger 14 Jepsen, Carly Rae Call Me Maybe 15 V.I.C. Wobble 16 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 17 Beatles Twist And Shout 18 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 19 Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Feat. Wanz Thrift Shop 20 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 21 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 22 Lmfao Feat. Lauren Bennett And Goon Rock Party Rock Anthem 23 Pink Raise Your Glass 24 Outkast Hey Ya! 25 Isley Brothers Shout 26 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 27 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 28 Mars, Bruno Marry You 29 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 30 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 31 Lumineers Ho Hey 32 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 33 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 34 Sister Sledge We Are Family 35 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 36 Temptations My Girl 37 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 38 Train Marry Me 39 Kool & The Gang Celebration 40 Daft Punk Feat. -

Let Creativity Happen! Grant 2019 Quarter Four Recipients

Let Creativity Happen! Grant 2019 Quarter Four Recipients 1. Belonging (or not) Abroad By Group Acorde Contemporary Dance and Live Music A collaborative work inspired by Brazilian culture from the perspective of a Brazilian choreographer and dancer residing in Houston for 17 years. As part of The Texas Latino/a Dance Festival, Group Acorde is showcasing the story of its co-director and co-founder Roberta Paixao Cortes through choreography and live music. 2. The Flower Garden of Ignatius Beltran By Adam Castaneda Modern Dance and Literary Arts The Flower Garden of Ignatius Beltran is an original dance work built by the community and performed by the community. This process-based work brings together both professional dancers and non-movers for a process and performance experience that attempts to dismantle the hierarchy and exclusionary practices of Western concert dance. 3. First Annual Texas Latino/a Contemporary Dance Festival By The Pilot Dance Project Modern Dance The Texas Latino/a Contemporary Dance Festival is the first convening of its kind that celebrates the choreographic voices of the Latin American diaspora of Houston. The festival is an initiative to make space for the Latino/a perspective in contemporary dance, and to accentuate the uniqueness of this work. 4. Mommy & Me Pop Up Libraries By Kenisha Coleman Literary Arts Mommy & Me Pop Up Library is a program designed to enrich the lives of mothers and their children through literacy, social engagement, culture, arts, and crafts. We will help to cultivate lifelong skills of learning, comprehension, language, culture, community, and creativity. We will also offer bilingual learning opportunities. -

Groupie Confessions! Pimps & Hoes! Real Talk: Adult Sex

GROUPIE CONFESSIONS! PIMPS & HOES! REAL TALK: ADULT SEX ED! THE THIRD ANNUAL SEX ISSUE FEATURING TRINA BOBBY VALENTINO BOHAGON DEM FRANCHIZE BOYZ FIELD MOB HEATHER HUNTER JIM JONES JODY BREEZE KILLER MIKE PETEY PABLO PRETTY RICKY REMY MA SHEEK LOUCH & STYLES P SLIM THUG SMITTY T-PAIN & YOUNG CASH TONY YAYO TRICK DADDY TRILLVILLE WEBBIE YING YANG TWINS & MORE GROUPIE CONFESSIONS! PIMPS & HOES! REAL TALK: ADULT SEX ED! FEATURING SMITTY BOBBY VALENTINO BOHAGON DEM FRANCHIZE BOYZ FIELD MOB HEATHER HUNTER JIM JONES JODY BREEZE KILLER MIKE PETEY PABLO PRETTY RICKY REMY MA SHEEK LOUCH SLIM THUG STYLES P T-PAIN TONY YAYO TRICK DADDY TRILLVILLE TRINA WARREN G WEBBIE YING YANG TWINS YOUNG CASH THE THIRD ANNUAL YOUNG JEEZY & MORE SEX ISSUE dec05contents PUBLISHER/EDITOR: Julia Beverly OPERATIONS MANAGER: Gary LaRochelle ADVERTISING SALES: COVER STORIES: Che’ Johnson (Gotta Boogie) Trina pg 34-36 LEGAL AFFAIRS: Kyle P. King, P.A. (King Law Firm) Smitty pg 84-87 ASSOCIATE EDITORS: Matt Sonzala, Maurice Garland MARKETING & PROMOTIONS: Malik “Highway” Abdul MUSIC EDITORS: ADG, Wally Sparks CAFFEINE SUBSTITUTES: Mercedes CONTRIBUTORS: Amanda Diva, Bogan, E-Feezy, Felita Knight, Iisha Hillmon, Jaro Vacek, Jessica Koslow, J Lash, Johnny Louis, Kamikaze, Keadron Smith, Keith Kennedy, K.G. Mosley, Killer Mike, King Yella, Lisa Coleman, Marcus DeWayne, Mayson Drake, Natalia Gomez, Noel Malcolm, Ray Tamarra, Rico Da Crook, Robert Gabriel, Rohit Loomba, Shannon McCollum, Spiff, Swift, Wendy Day STREET REPS: Al-My-T, B-Lord, Big Teach (Big Mouth), Bigg C, Bigg V, Black, Buggah D. Govanah (On Point), Bull, C Rola, Cedric Walker, Chill, Chilly C, Chuck T, Controller, Dap, Delight, Dolla Bill, Dwayne Barnum, Dr. -

Black Feminism Reimagined After Intersectionality Jennifer C. Nash

black feminism reimagined after intersectionality jennifer c. nash next wave New Directions in Women’s Studies A series edited by Inderpal Grewal, Caren Kaplan, and Robyn Wiegman jennifer c. nash black feminism reimagined after intersectionality Duke University Press Durham and London 2019 © 2019 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Courtney Leigh Baker and typeset in Whitman and Futura by Graphic Composition, Inc., Bogart, Georgia Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Nash, Jennifer C., [date] author. Title: Black feminism reimagined : after intersectionality / Jennifer C. Nash. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Series: Next wave | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2018026166 (print) lccn 2018034093 (ebook) isbn 9781478002253 (ebook) isbn 9781478000433 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9781478000594 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Womanism—United States. | Feminism— United States. | Intersectionality (Sociology) | Feminist theory. | Women’s studies—United States. | Universities and colleges— United States—Sociological aspects. Classification: lcc hq1197 (ebook) | lcc hq1197 .n37 2019 (print) | ddc 305.420973—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018026166 cover art: Toyin Ojih Odutola, The Uncertainty Principle, 2014. © Toyin Ojih Odutola. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. contents Acknowledgments vii introduction. feeling black feminism 1 1. a love letter from a critic, or notes on the intersectionality wars 33 2. the politics of reading 59 3. surrender 81 4. love in the time of death 111 coda. some of us are tired 133 Notes 139 Bibliography 157 Index 165 acknowledgments Over the course of writing this book, I moved to a new city, started a new job, and welcomed a new life into the world.