General Social Trust and Political Trust Within Social and Political Groups: a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ed 393 216 Author Title Report No Pub Date Available From

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 393 216 EA 027 482 AUTHOR Scribner, Jay D., Ed.; Layton, Donald H., Ed. TITLE The Study of Educational Politics. 1994 Commemorative Yearbook of the Politics of Education Association (1969-1994). Education Policy Perspectives Series. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7507-0419-5 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 225p. AVAILABLE FROM Falmer Press, Taylor & Francis, Inc., 1900 Frost Road, Suite 101, Bristol, PA 19007 (paperback: ISBN-0-7507-0419-5; clothbound: ISBN-0-7507-0418-7). PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Educational Principles; Educational Sociology; Elementary Secondary Education; Feminism; Ideology; International Education; *Policy Analysis; *Policy Formation; Political Influences; *Politics of Education; Role of Education; Values ABSTRACT This book surveys major trends in the politics of education over the last 25 years. Chapters synthesize political and policy developments at local, national, and state levels in the United States, as well as in the international arena. The chapters examine the emerging micropolitics of education and policy-analysis, cultural, and feminist studies. The foreword is by Paul E. Peterson and the introduction by Jay D. Scribner and Donald H.Layton. Chapters include:(1) "Values: The 'What?' of the Politics of Education" (Robert T. Stout, Marilyn Tallerico, and Kent Paredes Scribner) ;(2) "The Politics of Education: From Political Science to Interdisciplinary Inquiry" (Kenneth K. Wong);(3) "The Crucible of Democracy: The Local Arena" (Laurence Iannaccone and Frank W.Lutz); (4) "State Policymaking and School Reform: Influences and Influentials" (Tim L. Mazzoni);(5) "Politics of Education at the Federal Level" (Gerald E. Sroufe) ;(6) "The International Arena: The Global Village" (Frances C. -

Nlrcv20201.Pdf

1 2020 Nancy Lipton Rosenblum Senator Joseph S. Clark Professor of Ethics in Politics and Government, Emerita Harvard University Department of Government 1731 Cambridge St. Harvard University Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] Educational Background B.A., Radcliffe College, Social Studies, 1969 Ph.D., Harvard University Political Science, 1973 Teaching Positions Chair, Department of Government, Harvard University, 2004-2010 Senator Joseph S. Clark Professor of Ethics in Politics and Government, 2001 to 2016 Faculty Fellow, Safra Center for Ethics, Harvard University, 2003-4 Henry Merritt Wriston Professorship, Brown University, 1997- 2001 Chairperson, Political Science Department, Brown University, 1989-95 Professor, Brown University, 1980-2000 Liberal Arts Fellow, Harvard Law School, 1992-93 Fellow, Bunting Institute, Radcliffe College, 1988-89 Visiting Professor, Harvard University, Department of Government, Fall, 1985 Associate Professor, Department of Government, Harvard University, 1977-80 Henry LaBarre Jayne Assistant Professor, Department of Government, Harvard University, 1973-77 Publications Books A Lot of People are Saying: The New Conspiracism and the Assault on Democracy”, with Russell Muirhead (Princeton University Press, 2019) 2 Good Neighbors: The Democracy of Everyday Life in America (Princeton University Press, 2016) On the Side of the Angels: An Appreciation of Parties and Partisanship (Princeton University Press, 2008) Membership and Morals: The Personal Uses of Pluralism in America (Princeton University -

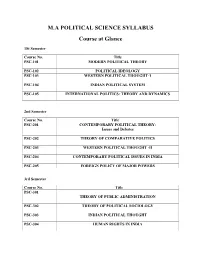

M.A POLITICAL SCIENCE SYLLABUS Course at Glance

M.A POLITICAL SCIENCE SYLLABUS Course at Glance 1St Semester Course No. Title PSC-101 MODERN POLITICAL THEORY PSC-102 POLITICAL IDEOLOGY PSC-103 WESTERN POLITICAL THOUGHT-1 PSC-104 INDIAN POLITICAL SYSTEM PSC-105 INTERNATIONAL POLITICS: THEORY AND DYNAMICS 2nd Semester Course No. Title PSC-201 CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL THEORY: Issues and Debates PSC-202 THEORY OF COMPARATIVE POLITICS PSC-203 WESTERN POLITICAL THOUGHT -II PSC-204 CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL ISSUES IN INDIA PSC-205 FOREIGN POLICY OF MAJOR POWERS 3rd Semester Course No. Title PSC-301 THEORY OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION PSC-302 THEORY OF POLITICAL SOCIOLOGY PSC-303 INDIAN POLITICAL THOUGHT PSC-304 HUMAN RIGHTS IN INDIA PSC-305 INDIA IN WORLD AFFAIRS 4th Semester Course No. Title PSC-401 CHANGING DIMENSIONS OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION IN INDIA PSC-402 INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZIATION AND ADMINISTRIATION PSC-403 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY PSC-404 COMPUTER BASICS: THEORY AND PRACTICE Elective CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL THOUGHT PSC-405 (i) 405 (ii) LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN INDIA 405 (iii) ETHICS AND POLITICS 405 (iv) COMPARATIVE FEDERALISM 405 (v) SOCIAL EXCLUSION IN INDIA Courses of Studies for M.A. in Political Science (Under Semester System of Teaching & Examination Effective from the Academic Session 2016-17) SEMESTER-I Course No. PSC-101 MODERN POLITICAL THEORY Unit-I (i) Political Theory- Evolution, The Traditional Approach; Nature and Scope of Traditional Political Theory; Prime Concerns. (ii) Modern Political Theory- Genesis and Evolution; The Modern Behavioural Approach; Nature and Scope of Modern Political Theory; Prime Concerns. Unit-II (i) Political Decision-making Theory of Harold. D. Laswell – The Concept of Politics as the Societal Decision-making Process; Classification of Societal Values; Role of Elites in the Societal Decision-making Process; Effectiveness and Legitimacy of the Societal Decision-making Structure. -

Political Education in the Elementary School: a Decision-Making Rationale

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-6748 COG AN, John Joseph, 1942- POLITICAL EDUCATION IN THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL: A DECISION-MAKING RATIONALE. The Ohio State U niversity, Ph.D., 1969 Education, theory and practice University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan (£) Copyright by John Joseph Cogan ,1970 POLITICAL EDUCATION IN THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL: A DECISION-MAKING RATIONALE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By John Joseph Cogan, B.S., M.A, ****** The Ohio State University 1969 Approved by College of Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This writer would like to extend hiB appreciation to all who provided guidance and help in any manner during the completion of this study. The writer is indebted immeasurably to his adviser, Professor Raymond H. Muessig, whose patient and continuous counsel made the completion of this study possible. Appreciation is also extended to Professors Robert E. Jewett and Alexander Frazier who served as readers of the dissertation. Finally, the writer is especially grateful to his wife, Norma, and hiB daughter, Susan, whose patience and understanding have been unfailing throughout the course of this study. ii VITA May 30, 19^2 . Born - Youngstown, Ohio 1 9 6 3. B.S., Kent State University, Kent, Ohio 1963-1965.... Elementary Teacher, Columbus Public Schools, Columbus, Ohio I965 ............ M.A., The Ohio State University, ColumbuB, Ohio 1965-1966 .... Graduate Assistant, College of Education, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1966-1967 .... United States Office of Education Fellow, Washington, D.C. Summer, 1967 . Acting Director, Consortium of Professional Associations for the Study of Special Teacher Improvement Programs (CONPASS), Washington, D.C. -

SS 12 Paper V Half 1 Topic 1B

Systems Analysis of David Easton 1 Development of the General Systems Theory (GST) • In early 20 th century the Systems Theory was first applied in Biology by Ludwig Von Bertallanfy. • Then in 1920s Anthropologists Bronislaw Malinowski ( Argonauts of the Western Pacific ) and Radcliffe Brown ( Andaman Islanders ) used this as a theoretical tool for analyzing the behavioural patterns of the primitive tribes. For them it was more important to find out what part a pattern of behaviour in a given social system played in maintaining the system as a whole, rather than how the system had originated. • Logical Positivists like Moritz Schilick, Rudolf Carnap, Otto Von Newrath, Victor Kraft and Herbert Feigl, who used to consider empirically observable and verifiable knowledge as the only valid knowledge had influenced the writings of Herbert Simon and other contemporary political thinkers. • Linguistic Philosophers like TD Weldon ( Vocabulary of Politics ) had rejected all philosophical findings that were beyond sensory verification as meaningless. • Sociologists Robert K Merton and Talcott Parsons for the first time had adopted the Systems Theory in their work. All these developments in the first half of the 20 th century had impacted on the application of the Systems Theory to the study of Political Science. David Easton, Gabriel Almond, G C Powell, Morton Kaplan, Karl Deutsch and other behaviouralists were the pioneers to adopt the Systems Theory for analyzing political phenomena and developing theories in Political Science during late 1950s and 1960s. What is a ‘system’? • Ludwig Von Bertallanfy: A system is “a set of elements standing in inter-action.” • Hall and Fagan: A system is “a set of objects together with relationships between the objects and between their attributes.” • Colin Cherry: The system is “a whole which is compounded of many parts .. -

American Political Science Association

A MERICAN P OLITICAL S CIENCE ASSOCIATION Assessing (In)Security after the Arab Spring John Gledhill, guest editor, April Longley Alley, Brian McQuinn, and Mohammad Ayatollahi Tabaar Misconceptions and Realities of the 2011 Tunisian Election Moez Habadou and Nawel Amrouche Political Science & Politics Katrina Seven Years On PSO CTOBER 2013, V OLUME 46, N UMBER 4 Christine L. Day American Political Science Association Make plans to attend the 2014 APSA Teaching & Learning Conference The 2014 APSA Teaching & Learning Conference theme is “Teaching Inclusively: Inte- grating Multiple Approaches into the Curriculum.” In this unique meeting, APSA strives to promote the greater understanding of cutting- edge approaches, techniques, and methodologies for the political science classroom. Using a working group format, the conference includes plenaries, tracks, and work- shops on topics such as: t Civic Engagement t Integrating Technology in the t Conflict and Conflict Resolution Classroom t Core Curriculum/General t Internationalizing the Curriculum Education t Teaching and Learning at Community t Curricular and Program Assessment Colleges t Distance Learning t Professional Development t Diversity, Inclusiveness, and Equality t Simulations and Role Play t Graduate Education: Teaching and t Teaching Political Theory and Theories Advising Graduate Students t Teaching Research Methods www.apsanet.org/teachingconference 1527 New Hampshire Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20036 | 202.483.2512 | www.apsanet.org ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Political Science & Politics

Political Science & Politics Volume XXI Number 2 Spring 1988 "/ <£lVE. TbU A MAM WHO 6 RELI&10U5, QUX Cb NO fAhKTlc; A MAM VVHO ^V&RS ^ ro A eo/Mr; /\ MAN WHO LIKES Private Lives and Public Careers Bruce Buchanan, Ronald Elving and Sanford Levinson 1988 Annual Meeting Preview Chatham House Checklist Box One, Chatham, NJ 07928 Telephone: (201) 635-2059 * Arian: Politics in Israel it Ball: Modern Politics and Government 4ed * Cannon and O'Brien: Views from the Bench * Dalton: Citizen Politics in Western Democracies * Dogan and Pelassy: How to Compare Nations * Dolbeare: American Political Thought * Dolbeare: Democracy at Risk rev ed * Dragnich et al.: Politics and Government 2ed •sir Fry: Masters of Public Administration it Godwin: Direct Marketing of Politics * Goodsell: The Case for Bureaucracy 2ed •sir Hancock: West Germany •sir Hancock et al.: Politics in Western Europe ~k Hershey: Running for Office it Hinckley: The Symbolic Presidency * Hood: Tools of Government * Jacobs et al.: Comparative Politics * Jones: The Reagan Legacy * Kaufman: Time, Chance, and Organizations * King: The State in Modern Society it Lynn &. Wildavsky: Public Administration * McFarland: Common Cause * Meehan: The Thinking Game: A Guide to Effective Study * Orren and Polsby: Media and Momentum: New Hampshire * Peters: American Public Policy 2ed •sir Rose: The Post-Modern Presidency * Sartori: The Theory of Democracy Revisited * Savas: Privatization: The Key to Better Government * Wilson: Business and Politics * Published it Forthcoming On your request for exam copies, please state course title, present text, and enrollment on your letterhead and send it to Edward Artinian, publisher, Chatham House Publishers, Inc., Box One, Chatham, New Jersey 07928 or telephone (201) 635-2059. -

Human Development and Generalized Trust: Multilevel Evidence

Anna Almakaeva1, Eduard Ponarin2, Christian Welzel3 HUMAN DEVELOPMENT AND GENERALIZED TRUST: MULTILEVEL EVIDENCE Generalized trust is one of the most debated topics in social sciences. A flood of papers attempting to examine its foundations has been published over the last few decades. However, only a handful of studies incorporates a multilevel approach and investigates how macro conditions shape the individual determinants of generalized trust. This investigation seeks to fill this gap, using the broad sample of the fifth round of the World Values Survey, multilevel regression modeling, human development as country-level moderator and trust in unknown people as a more perfect measure of generalized trust. We took six theories of trust origin suggested by Delhey and Newton (2003) as a starting point, and demonstrate that along with common factors (such as particularized trust and confidence in institutions), generalized trust can be influenced by a set of specific determinants which differ depending on the level of human development. In poorly developed societies, financial satisfaction was the only indicator that fostered generalized trust, while education decreased it. In highly developed countries it was active membership, open-access activities, emancipative values, age and education which contributed to the strengthening of trust. Key words: generalized trust, trust radius, trust theories, human development, multilevel regression modeling, moderation effect JEL: C21, D64 1 Laboratory for Comparative Social Research, HSE, Russia, [email protected] 2 Laboratory for Comparative Social Research, HSE, Russia, [email protected] 3 Leuphana University Lueneburg, Germany; Laboratory for Comparative Social Research, HSE, Russia, [email protected] 1. Introduction Trust, one of the most important ingredients for social life, eases human interactions and creates a solid basis for prolonged and successful cooperation between people. -

Foundation of Political Science

School of Distance Education UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION I SEMESTER B.A POLITICAL SCIENCE (2013 ADMISSION) CORE COURSE FOUNDATION OF POLITICAL SCIENCE QUESTION BANK 1. Who defined political science is “that part of social science which treats the foundations of the foundations of the state and principles of government”? a. Paul Janet; b. Dyke; c. Gettell; d. None of it 2. Who is the author of “A History of Political Theory”? a. Karl Popper; b. Sabine; c. Mill; d. Locke 3. Who described historical approach as ‘historicism’? a. Bentham; b. Hegel; c. Popper; d. Marx 4. Which approach is, according to Rober A Dahl, an attempt to make the empirical content of Political Science more scientific “ a. Institutional Approach c. Philosophical Approach b. Historical Approach d. Behavioural Approach 5. Who introduced ‘intellectual foundations’ for behavioural approach? a. Easton; b. Merriam; c. Lasswell; d. Bentley 6. Who said “the concept of power is the most fundamental in the whole of Political Science: the Political Process is the shaping, dissolution and exercise of power” ? a. Merriam and Easton c. Catlin and Bentley b. Lasswell and Kaplan d. None of them 7. Who is known as the greatest advocate of Post-Behaviouralism? a. Merriam; b. Easton; c. Lasswell; d. Bentley 8. Which approach demands ‘relevance’ and ‘action’? a. Institutional Approach c. Behaviouralist b. Post-Behaviouralist Approach d. Historical Approach 9. Whose definition encompasses the ‘politics of consent’ as well as the ‘politics of struggle’? a. Easton; b. Merriam; c. Lasswell; d. Kaplan 10. Who introduced ‘politics of consent’ ? a. Lasswell; b. -

Humans Adapt to Social Diversity Over Time

Humans adapt to social diversity over time Miguel R. Ramosa,b,1, Matthew R. Bennettc, Douglas S. Masseyd,1, and Miles Hewstonea,e aDepartment of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, Oxford OX2 6AE, United Kingdom; bCentro de Investigação e de Intervenção Social, Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), 1649-026 Lisboa, Portugal; cDepartment of Social Policy, Sociology and Criminology, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom; dOffice of Population Research, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544; and eSchool of Psychology, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia Contributed by Douglas S. Massey, March 1, 2019 (sent for review November 2, 2018; reviewed by Oliver Christ, Kathleen Mullan Harris, and Mary C. Waters) Humans have evolved cognitive processes favoring homogeneity, (21) recognizes that humans share an impulse to engage in contact stability, and structure. These processes are, however, incompatible with other people, even those in outgroups. Indeed, biological and with a socially diverse world, raising wide academic and political cultural anthropology contend that humans have evolved and concern about the future of modern societies. With data comprising fared better than other species because contact with outgroups 22 y of religious diversity worldwide, we show across multiple brings a variety of benefits that cannot be attained by intragroup surveys that humans are inclined to react negatively to threats to interactions. There is, for example, a biological advantage to homogeneity (i.e., changes in diversity are associated with lower gaining genetic variability through new mating opportunities (22) self-reported quality of life, explained by a decrease in trust in and intergroup contact allows individuals access to more diverse others) in the short term. -

Storefront Toolkit: Understanding and Measuring “Trust” by Haifa Alarasi, Ma Liang & Stuart Burkimsher Instructor: Professor Susan Ruddick

PLA1503 – Planning and Social Policy Storefront Toolkit: Understanding and Measuring “Trust” By Haifa Alarasi, Ma Liang & Stuart Burkimsher Instructor: Professor Susan Ruddick Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................... iii Research Strategy ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Trust vs. Social Capital ........................................................................................................................... 2 What Does the Term “Social Capital” Mean? ..................................................................................... 2 Bonding, Bridging, Linking ................................................................................................................... 3 Solidarity & Reciprocity ......................................................................................................................... 4 “Trust” as A Conceptual Model ............................................................................................................ 5 Measuring Trust: Methods & Case Studies From the Literature .......................................................... 7 Building Informal Trust: A Few Findings ........................................................................................... -

Generalized Trust and Economic Growth: the Nexus in MENA Countries

economies Article Generalized Trust and Economic Growth: The Nexus in MENA Countries Rania S. Miniesy * and Mariam AbdelKarim Department of Economics, The British University in Egypt, El Sherouk City 11837, Egypt; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This study mainly examines the relationship between generalized/horizontal/social trust and economic growth in countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, considering the substantial decline in their trust values since 2005. The study utilizes a multiple linear regression model based on panel data comprising 104 countries over the period from 1999 to 2020. Trust data were obtained from the last four waves of the World Values Survey (WVS). A Pooled Ordinary Least Squares (POLS) estimation technique was used, and interaction terms between trust and several dummy variables were employed. The results show an overall positive and significant relation- ship between trust and economic growth in the general model and for all country classifications, except for MENA, where the overall relationship is negative but almost negligible. Trust has the highest impact on growth in transition economies, followed in order by developing Asia, developed, developing/Sub-Saharan Africa, developing America, and then MENA countries. Further investiga- tions reveal that the overall negative/reversed effect of trust on economic growth in MENA is only during waves 6 and 7, where the coefficients are sizable. Keywords: generalized trust; horizontal trust; social trust; social capital; economic growth; democ- racy; MENA; developing countries; Arab Spring; WVS Citation: Miniesy, Rania S., and JEL Classification: O17; O43; O57 Mariam AbdelKarim. 2021. Generalized Trust and Economic Growth: The Nexus in MENA Countries.