Cultural Dilemmas in Public Service Broadcasting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BBC AR Front Part 2 Pp 8-19

Executive Committee Greg Dyke Director-General since Jana Bennett OBE Director of Mark Byford Director of World customer services and audience January 2000, having joined the BBC Television since April 2002. Service & Global News since research activities. Previously as D-G Designate in November Responsible for the BBC’s output October 2001. Responsible for all European Director for Unilever’s 1999. Previously Chairman and Chief on BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three the BBC’s international news and Food and Beverages division. Former Executive of Pearson Television from and BBC Four and for overseeing information services across all media positions include UK Marketing 1995 to 1999. Former posts include content on the UKTV joint venture including BBC World Service radio, Director then European Marketing Editor in Chief of TV-am (1983); channels and the international BBC World television and the Director with Unilever’s UK Food Director of Programmes for TVS channels BBC America and BBC international-facing online news and Beverages division and (1984), and Director of Programmes Prime. Previously General Manager sites. Previously Director of Regional Chairman of the Tea Council. (1987), Managing Director (1990) and Executive Vice President at Broadcasting. Former positions and Group Chief Executive (1991) at Discovery Communications Inc. include Head of Centre, Leeds and Carolyn Fairbairn Director of London Weekend Television. He has in the US. Former positions include Home Editor Television News. Strategy & Distribution since April also been Chairman of Channel 5; Director of Production at BBC; Head 2001. Responsible for strategic Chairman of the ITA; a director of BBC Science; Editor of Horizon, Stephen Dando Director of planning and the distribution of BBC of ITN, Channel 4 and BSkyB, and and Senior Producer on Newsnight Human Resources & Internal services. -

Revisiting Transnational Media Flow in Nusantara: Cross-Border Content Broadcasting in Indonesia and Malaysia

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 49, No. 2, September 2011 Revisiting Transnational Media Flow in Nusantara: Cross-border Content Broadcasting in Indonesia and Malaysia Nuurrianti Jalli* and Yearry Panji Setianto** Previous studies on transnational media have emphasized transnational media organizations and tended to ignore the role of cross-border content, especially in a non-Western context. This study aims to fill theoretical gaps within this scholarship by providing an analysis of the Southeast Asian media sphere, focusing on Indonesia and Malaysia in a historical context—transnational media flow before 2010. The two neighboring nations of Indonesia and Malaysia have many things in common, from culture to language and religion. This study not only explores similarities in the reception and appropriation of transnational content in both countries but also investigates why, to some extent, each had a different attitude toward content pro- duced by the other. It also looks at how governments in these two nations control the flow of transnational media content. Focusing on broadcast media, the study finds that cross-border media flow between Indonesia and Malaysia was made pos- sible primarily in two ways: (1) illicit or unintended media exchange, and (2) legal and intended media exchange. Illicit media exchange was enabled through the use of satellite dishes and antennae near state borders, as well as piracy. Legal and intended media exchange was enabled through state collaboration and the purchase of media rights; both governments also utilized several bodies of laws to assist in controlling transnational media content. Based on our analysis, there is a path of transnational media exchange between these two countries. -

Li4j'lsl!=I 2 Leeds Student Ma Aj Rnutidoo ®~1 the Bulk of Landlords .Trc \.\Ith News Ump,.'11

THE REVOLT T F TH HT --FULL STORY PAGE NINE -----li4J'lSl!=I 2 www.leedsstudentorg.uk Leeds Student ma aJ rnutIDoo ®~1 the bulk of landlords .trc \.\ith News Ump,.'11. 20 per ce n1 uren ·1 and LIBERAL Democnil MP in the ..crabbl c 10 find holbm,1: S0%of Simon llu~ht-s has helped in LS6. .., ,uden~ forgc1 11t.11 kick-start a new student the) have nghl\." students have hou."iing crlCMJdc. Jame:; Blake, pre,;idenJ ot taken drugs lhc ·m1111 campaign . Ll'l I\ Lib Dem pan), said but they want wluch I\ be ing c;pearheadc<l h) ·-rm so plc:t5cd thut Simon the:" J~ll:, LT111vcr-.U) L1h rkm Hughe!. could launt:h th 1.:. stricter laws part). •~ .ummg In _maJ..i: c:1mpa1~.n· i1 ,hows YrC an• pt.-<1ple more aware. ol 1he1r ',C.."OOU!, nglu .. :L, IC/M Ii t.. Hu~hC!-i. \\ ho was narmwl} pages TennnL!- can dl!m.Jnd 1h i 11 w, hct11cn by Charles Kenned)- in like ',llltllu: de1cc1or... gu~ a le..ader.; lup contest. ~ id: {ee:-. for appl i,mcc\ and '"StuJcn1 .-. olten fc.el 1hat Uni of Leeds found wanting by aik-qualc 101.;b. filling,. becau~ they mm,e around 11 \ government watchdogs Greg Mulholland. a t.-01111 not '-"Onh \. Otmg. We wam 10 tell lhem lh:it ii I\, nnd lhat pages 6 · 7 cillur for l.ttJs ~fonh \\'1....,1 who i.. .il!.O baekm!! the wc · n: n:lc\'an1 ...chcme. ,,;md: ··1t\ the ... mall "If ~IUdent.,;. -

Crying with Tags

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository This item was submitted to Loughborough’s Institutional Repository (https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/) by the author and is made available under the following Creative Commons Licence conditions. For the full text of this licence, please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ __________________________________________________________________________________________ DISCURSIVE CONSTRUCTIONISM __________________________________________________________________________________________ Jonathan Potter & Alexa Hepburn Discourse and Rhetoric Group Email: [email protected] Department of Social Sciences Tel: 01509 223384 Loughborough University Email: [email protected] Loughborough Tel: 01509 223364 Leicestershire, LE11 3TU We would like to thank Derek Edwards, Elizabeth Stokoe and the editors of this volume for thoughtful comments on an earlier draft. To appear as: Potter, J. & Hepburn, A. (forthcoming). Discursive constructionism. In Holstein, J.A. & Gubrium, J.F. (Eds). Handbook of constructionist research. New York: Guildford. Final draft December 2006 0 INTRODUCTION Discursive constructionism (henceforth sometimes DC) is most distinctive in its foregrounding of the epistemic position of both the researcher and what is researched (texts or conversations). It studies a world of descriptions, claims, reports, allegations and assertions as parts of human practices, and it works to keep these as the central topic of research rather than trying to move beyond them to the objects or events that seem to be the topic of such discourse. It is radically constructionist in that it is sceptical of any guarantee beyond local and contingent texts, claims, arguments, demonstrations, exercises of logic and procedures of empiricism and so on. -

The Concepts and Methods of Phenomenographic Research

Review of Educational Research Spring 1999, Voi. 69, No. 1, pp. 53-82 The Concepts and Methods of Phenomenographic Research John T. E. Richardson Brunel University This article reviews the nature'of "phenomenographic" research and its alleged conceptual underpinnings in the phenomenological tradi- tion. In common with other attempts to apply philosophical phenom- enology to the social sciences, it relies on participants' discursive accounts of their experiences and cannot validly postulate causal men- tal entities such as conceptions of learning. The analytic procedures of phenomenography are very similar to those of grounded theory, and like the latter they fall foul of the "dilemma of qualitative method" in failing to reconcile the search for authentic understanding with the need for scientific rigor. It is argued that these conceptual and meth- odological difficulties could be resolved by a constructionist revision of phenomenographic research. During the last 25 years research on student learning in higher education has benefited immensely from a distinctive qualitative approach known as "phenomenography." This is associated with Ference Marton and his colleagues at the University of Gtteborg in Sweden, although it has been taken up by many other researchers in Australia, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. Marton (1986, 1988b) described phenomenography as an empirically based approach that aims to identify the qualitatively different ways in which differ- ent people experience, conceptualize., perceive, and understand various kinds of phenomena. Within this framework, learning assumes a central importance, be- cause it represents a qualitative change from one conception concerning some particular aspect of reality to another (Marton, 1988a). In this paper, I argue that a proper evaluation of the phenomenographic approach has in the past been bedevilled by a lack of specificity and explicit- ness concerning both the methods for the collection and analysis of data and the conceptual underpinning of those methods (cf. -

Appendix A: Non-Executive Directors of Channel 4 1981–92

Appendix A: Non-Executive Directors of Channel 4 1981–92 The Rt. Hon. Edmund Dell (Chairman 1981–87) Sir Richard Attenborough (Deputy Chairman 1981–86) (Director 1987) (Chairman 1988–91) George Russell (Deputy Chairman 1 Jan 1987–88) Sir Brian Bailey (1 July 1985–89) (Deputy Chairman 1990) Sir Michael Bishop CBE (Deputy Chairman 1991) (Chairman 1992–) David Plowright (Deputy Chairman 1992–) Lord Blake (1 Sept 1983–87) William Brown (1981–85) Carmen Callil (1 July 1985–90) Jennifer d’Abo (1 April 1986–87) Richard Dunn (1 Jan 1989–90) Greg Dyke (11 April 1988–90) Paul Fox (1 July 1985–87) James Gatward (1 July 1984–89) John Gau (1 July 1984–88) Roger Graef (1981–85) Bert Hardy (1992–) Dr Glyn Tegai Hughes (1983–86) Eleri Wynne Jones (22 Jan 1987–90) Anne Lapping (1 Jan 1989–) Mary McAleese (1992–) David McCall (1981–85) John McGrath (1990–) The Hon. Mrs Sara Morrison (1983–85) Sir David Nicholas CBE (1992–) Anthony Pragnell (1 July 1983–88) Usha Prashar (1991–) Peter Rogers (1982–91) Michael Scott (1 July 1984–87) Anthony Smith (1981–84) Anne Sofer (1981–84) Brian Tesler (1981–85) Professor David Vines (1 Jan 1987–91) Joy Whitby (1981–84) 435 Appendix B: Channel 4 Major Programme Awards 1983–92 British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) 1983: The Snowman – Best Children’s Programme – Drama 1984: Another Audience With Dame Edna – Best Light Entertainment 1987: Channel 4 News – Best News or Outside Broadcast Coverage 1987: The Lowest of the Low – Special Award for Foreign Documentary 1987: Network 7 – Special Award for Originality -

The Analysis of the Driving Factors of Turkish Foreign

THE ANALYSIS OF THE DRIVING FACTORS OF TURKISH FOREIGN POLICY FROM ASSERTIVENESS TO PRAGMATISM IN CASE OF TURKEY – ISRAEL RECONCILIATION ON THE MAVI MARMARA FLOTILLA INCIDENT (2010 – 2016) By MUHAMMAD ADNAN FATRON ID No. 016201300101 A Thesis presented to the Faculty of Humanities President University in partial fulfillment of the requirement of Bachelor Degree in International Relations Major in Security and Strategic Defense Studies 2017 THESIS ADVISER RECOMMENDATION LETTER Thesis entitled “THE ANALYSIS OF THE DRIVING FACTORS OF TURKISH FOREIGN POLICY FROM ASSERTIVENESS TO PRAGMATISM IN CASE OF TURKEY – ISRAEL RECONCILIATION ON THE MAVI MARMARA FLOTILLA INCIDENT (2010 – 2016)” prepared and submitted by Muhammad Adnan Fatron in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor in the Faculty of Humanities had been reviewed and found to have satisfied the requirements for a thesis fit to be examined. I therefore recommend this thesis for Oral Defense. Cikarang, Indonesia, January 24th 2017. Recommended and Acknowledged by, Drs. Teuku Rezasyah, M.A., Ph.D. i DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I declare that this thesis entitled “THE ANALYSIS OF THE DRIVING FACTORS OF TURKISH FOREIGN POLICY FROM ASSERTIVENESS TO PRAGMATISM IN CASE OF TURKEY – ISRAEL RECONCILIATION ON THE MAVI MARMARA FLOTILLA INCIDENT (2010-2016)” is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, an original piece of work that has not been submitted, either in whole or in part, to another university to obtain a degree. Cikarang, Indonesia, January 24th 2017 Muhammad -

Leisure Opportunities 20Th September 2016 Issue

Find great staffTM leisure opportunities 20 SEPTEMBER - 3 OCTOBER 2016 ISSUE 693 Daily news & jobs: www.leisureopportunities.co.uk ukactive: Tech to ‘transform fitness’ Health club members expect there is hope for club operators wearable technology and too, as a clear majority (66 per Netflix-style workout services cent) cite the gym as their main to “transform” their gym way of keeping fit – now and in experience over the next decade. the future. That is the headline finding When it comes to predicting of a study commissioned by what a future health club could ukactive and retailer Argos look like, expectations include which quizzed more than 1,000 anti-gravity workout rooms fitness fans on what they expect and machines that ‘trick fitness to look like in 2026. muscles’ into thinking they’re Two thirds (66 per cent) working out. of respondents believe Baroness Tanni Grey- technological advances will help Thompson, ukactive chair, keep them fitter, while more than said: “As physical activity and half think wearable technology technology align, we’re entering will dictate their workouts. a brave new world with exciting One in five (20 per cent) Technological advances such as virtual fitness are expected to transform the sector opportunities to get people think virtual reality will allow more active. With two thirds them to work out with their favourite athletes (22 per cent) expecting roads to have jogging of those questioned expecting to be fitter in in their own living rooms and more than half lanes next to cycling lanes, while 8 per cent future, there is growth potential for the sector.” (57 per cent) expect to engage virtually with think drones will be on hand to encourage Undertaken in July 2016, the study of personal trainers via TVs and computers. -

Social Representations and Discursive Psychology

Culture & Psychology http://cap.sagepub.com/ Social Representations and Discursive Psychology: From Cognition to Action Jonathan Potter and Derek Edwards Culture Psychology 1999 5: 447 DOI: 10.1177/1354067X9954004 The online version of this article can be found at: http://cap.sagepub.com/content/5/4/447 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Culture & Psychology can be found at: Email Alerts: http://cap.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://cap.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://cap.sagepub.com/content/5/4/447.refs.html >> Version of Record - Dec 1, 1999 What is This? Downloaded from cap.sagepub.com at NORTH DAKOTA STATE UNIV LIB on October 28, 2014 Commentary Abstract This article compares and contrasts the way a set of fundamental issues are treated in social representations theory and discursive psychology. These are: action, representation, communication, cognition, construction, epistemology and method. In each case we indicate arguments for the discursive psychological treatment. These arguments are then developed and illustrated through a discussion of Wagner, Duveen, Themel and Verma (1999) which highlights in particular the way the analysis fails to address the activities done by people when they are producing representations, and the epistemological troubles that arise from failing to address the role of the researcher’s own representations. Key Words -

Efficiency and Rentability of Introducing DVB-T2 HEVC System in Germany and Croatia

WSEAS TRANSACTIONS on BUSINESS and ECONOMICS DOI: 10.37394/23207.2020.17.92 Fran Galetic Technological Progress in Terrestrial Television Transmitting – Efficiency and Rentability of Introducing DVB-T2 HEVC System in Germany and Croatia FRAN GALETIC Faculty of Economics and Business University of Zagreb Trg J.F. Kennedyja 6, 10000 Zagreb CROATIA Abstract: - Germany and Croatia are among first European countries that have adopted the strategy of switching from DVB-T h.264 system to DVB-T2 h.265 (HEVC) system of broadcasting for terrestrial television. The newer h.265 system has better performance compared to previously h.264 especially in terms of efficiency of transmitting. On a single frequency, h.265 enables much more data flow, which means more channels and/or better quality of transmitting. This paper investigates the efficiency and rentability of such transition and compares Germany as s big and Croatia as a small European country. The aim of the analysis is to show the background for such a technological change in these two countries and to compare it having in mind the difference of capacities necessary for terrestrial transmission. This switch to the DVB-T2 HEVC system represents the classical example of technological progress in practice, and is especially interesting in the period when other countries are setting up strategies for the future of terrestrial television transmission. Key-Words: - Terrestrial television; DVB-T; DVB-T2; HEVC; Germany; Croatia Received: August 5, 2019. Revised: September 14, 2020. Accepted: September 21, 2020. 1 Introduction resolution 720x576, while HDTV is using The most significant switch in television was the 1920x1080 resolution. -

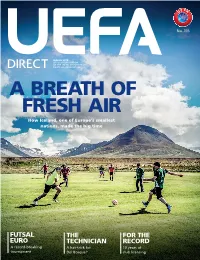

UEFA"Direct #155 (01.03.2016)

No. 155 MARCH 2016 OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE UNION OF EUROPEAN FOOTBALL ASSOCIATIONS A BREATH OF NONO TOTO RACISMRACISM FRESH AIR How Iceland, one of Europe’s smallest nations, made the big time No.155 • March 2016 • March No.155 FUTSAL THE FOR THE EURO TECHNICIAN RECORD A record-breaking A hat-trick for 10 years of tournament Del Bosque? club licensing BIRTHDAYS, COMMUNICATIONS, FORTHCOMING EVENTS BIRTHDAYS Jim Boyce (Northern Ireland, 21 March) Alan Snoddy (Northern Ireland, 29 March) Kai-Erik Arstad (Norway, 21 March) Bernadette Constantin (France, 29 March) Denis Bastari (Albania, 21 March) Bernadino González Vázquez (Spain, Benny Jacobsen (Denmark, 1 March) Ginés Meléndez (Spain, 22 March) 29 March) 50th Luis Medina Cantalejo (Spain, 1 March) Chris Georghiades (Cyprus, 22 March) Sanna Pirhonen (Finland, 29 March) Damir Vrbanović (Croatia, 2 March) Michail Kassabov (Bulgaria, 22 March) William Hugh Wilson (Scotland, 30 March) Jenni Kennedy (England, 2 March) Pascal Fritz (France, 25 January) Richard Havrilla (Slovakia, 31 March) 50th Hans Lorenz (Germany, 3 March) Luca Zorzi (Switzerland, 22 March) Marina Mamaeva (Russia, 31 March) Zbigniew Boniek (Poland, 3 March) 60th Hugo Quaderer (Liechtenstein, 22 March) Matteo Simone Trefoloni (Italy, 31 March) Alexandru Deaconu (Romania, 3 March) Pafsanias Papanikolaou (Greece, Carolin Greiner Mai (Germany, 3 March) 22 March) 40th François Vasseur (France, 3 March) Andrew Niven (Scotland, 22 March) COMMUNICATIONS Patrick McGrath (Republic of Ireland, Franz Krösslhuber (Austria, 23 March) -

Atributos De Séries Dramáticas De Sucesso E Engajamento Da Audiência Successful Drama TV Series // Features and Audience Engagement

DOI: 10.11606/issn.2316-7114.sig.2018.143013 Atributos de séries dramáticas de sucesso e engajamento da audiência Successful drama TV series // features and audience engagement //////////////// Sílvio Antonio Luiz Anaz1 1 Pesquisador de pós-doutorado em Meios e Processos Audiovisuais na Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo (ECA- USP). Doutor em Comunicação e Semiótica pela Pontifícia Universidade Católica (PUC-SP). E-mail: [email protected] Significação, São Paulo, v. 45, n. 50, p. 239-258, jul-dez. 2018 | 239 //////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// Atributos de séries dramáticas de sucesso e engajamento da audiência | Sílvio Antonio Luiz Anaz Resumo: parte das séries dramáticas da TV caracteriza-se pela hibridação dos formatos episódico e serial, universo expandido (transmídia), engajamento da audiência e arcos longos que aprofundam as características dos personagens. Este artigo analisa esse fenômeno a partir da identificação das principais especificidades dos processos contemporâneos de criação e de fruição das séries televisivas para, em seguida, mapear e descrever os recursos que têm se destacado e contribuído para o seu êxito. Os resultados mostram a importância do papel do showrunner, da lógica de produção e consumo dos canais por assinatura e do uso de recursos narrativos desafiadores para a audiência no sucesso dessas séries. Palavras-chave: série de TV; narrativa complexa; série dramática; engajamento da audiência; processo criativo. Abstract: some contemporary drama TV series are characterized by hybrid format (serial and episodic), expanded universe (transmedia), audience engagement, and long arcs that elaborate on personage’s characteristics. This paper analyzes this phenomenon in two steps: first, it establishes the main specificities in contemporary creation and fruition processes of TV series; second, it maps and delineates the outstanding resources that have contributed to their success.