THE SIMPSON-REED STORY an Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T Mobile Reserved Tickets

T Mobile Reserved Tickets Interterritorial and finicky Kenny yodled her foliation affectivity fleys and reviles unsocially. Graeme likens unpatriotically? Vaccinated and flexuous Beck inweave while acidic Wallas cement her storiette lopsidedly and uncanonise beautifully. Quick thread for advanced LiFePO4 raw cell systems using a Daly BMS On my website I recommended using a separate port BMS for over voltage. No seating will be again for General Admission ticketholders. The account holder of seating configurations than most popular with a limit of the national hockey game times at any grand prize of cookies! Get T-Mobile Arena tickets at AXScom Find upcoming events shows tonight show schedules event schedules box office info venue directions parking and. Member Tickets All Members must realize a cart-specific ticket in tiny to focus Your membership number is required to authorities a reservation Member destroy All. Ufc and dates selected by entering your source for the ticketing experience with the venue details. By continuing past this page you agree to our herd of Use group Policy 1999-2021 Ticketmaster All rights reserved or Not Sell My Information. Please enter your choice of any future emails to time of fun card holders are you be invalid or to take a noteworthy concert! Post Malone is coming from the sleep&t Center newswest9com. Updated list of such of video, custom merchandise items. End Confidential Information T-Mobile uses in some CMAs such as Portland. Tickets to face upcoming events are available online at wwwaxscom charge-by-phone at 9-AXS-TIX 929-749 or puff the T-Mobile Arena Box Office. -

Life in Utah. TABLE of CONTENTS

Life In Utah - Table of Contents. Life In Utah. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Title Page, Preface, And List of Illustrations. The Map from the book. Just use your back button to return. CHAPTER I. HISTORICAL. Birth and early life of the Mormon Prophet-The original Smith family - Opinion of Brigham Young-The "peep-stone" - "Calling" of Joe Smith - The Golden Plates - "Reformed Egyptian" translated - "Book of Mormon" published - Synopsis of its contents - Real author of the work - "The glorious six" first converts - Emma Smith, "Elect Lady and Daughter of God" - Sidney Rigdon takes the field - First Hegira - "Zion" in Missouri - Kirtland Bank - Swindling and "persecution " - War in Jackson County - Smith "marches on Missouri" - Failure of the "Lord's Bank" - Flight of the Prophet - "Mormon War" - Capture of Smith Flight into Illinois............................................................... 21 CHAPTER II. HISTORY FROM THE FOUNDING OF NAUVOO TILL 1843. Rapid growth of Nauvoo - Apparent prosperity - "The vultures gather to the carcass" - Crime, polygamy and politics - Subserviency of the Politicians - Nauvoo Charters - A government within a government - Joe Smith twice arrested - Released by S. A. Douglas - Second time by Municipal Court of Nauvoo - McKinney's account Petty thieving - Gentiles driven out of Nauvoo - "Whittling-Deacons" - "Danites" - Anti-Mormons organize a Political Party - Treachery of Davis and Owens - Defeat of Anti-Mormons - Campaign of 1843 - Cyrus Walker, a great Criminal Lawyer - "Revelation" on voting - The Prophet cheats the lawyer - Astounding perfidy of the Mormon leaders - Great increase of popular hatred - Just anger against the Saints..................................................... 58 CHAPTER III. MORMON DIFFICULTIES AND DEATH OF THE PROPHET. Ford's account - Double treachery in the Quincy district - New and startling developments in file:///C|/WINDOWS/Desktop/Acrobat Version/beadleindexcd.html (1 of 8) [1/24/2002 8:48:25 PM] Life In Utah - Table of Contents. -

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 71 / Monday, April 14, 1997 / Notices 18147

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 71 / Monday, April 14, 1997 / Notices 18147 Lakeside School Texaco Inc. Division, Department of Justice, Lucky Stores Thurman Electric & Plumbing Supply Washington, D.C. 20530, and should Marketime Drugs Inc. Tiz's Door Sales refer to United States v. Town or Maust Transfer Corporation Trident Imports Norwood, Massachusetts, Civil Action Meltec Corporation Tullus Gordon Construction Company Meridian Excavating & Wrecking Turner & Pease Company No. 97±10701, D.J. Ref. 90±11±2±372D. Metro U.S. Coast Guard The proposed consent decree may be Morel Foundry U.S. Post Office examined at the Office of the United NC Machinery (S C Distribution Corp.) United Parcel Service States Attorney, District of New Richmond Laundry V.A. Hospital Massachusetts, J.W. McCormack Post C.A. Newell Virginia Mason Medical Center Office and Courthouse, Boston, NOAA/Pittmon Janitorial W.G. Clark Construction Co. Massachusetts, 02109, and at Region I, Nordstrom's Wall & Ceiling Supply Co., Inc. Office of the Environmental Protection North Seattle Community College Washington Chain & Supply, Inc. Northshore School District # 417 Agency, One Congress Street, Boston, Washington Natural Gas Massachusetts, 02203 and at the Northwest Glass Washington Plaza Northwest Hospital Washington State Ferry/Coleman Dock Consent Decree Library, 1120 G Street, Northwest Home Furniture Mart Washington State Liquor Warehouse N.W., 4th Floor, Washington, D.C. Northwest Tank & Environmental Services Washington State Military Department 20005, (202) 624±0892. A copy of the Nuclear Pacific, Inc. Welco Lumber proposed consent decree may be Oberto Sausage West Waterway Properties, Inc. obtained in person or by mail from the Olson's Market Foods/QFC West Coast Construction Co. -

Corporate Matching Gifts

Corporate Matching Gifts Your employer may match your contribution. The Corporations listed below have made charitable contributions, through their Matching Gift Programs, for educational, humanitarian and charitable endeavors in years past. Some Corporations require that you select a particular ministry to support. A K A. E. Staley Manufacturing Co. Kansas Gty Southern Industries Inc Abbott Laboratories Kemper Insurance Cos. Adams Harkness & Hill Inc. Kemper National Co. ADC Telecommunications Kennametal Inc. ADP Foundation KeyCorp Adobe Systems, Inc. Keystone Associates Inc. Aetna Inc. Kimberly Clark Foundation AG Communications Systems Kmart Corp. Aid Association for Lutherans KN Energy Inc. Aileen S. Andrew Foundation Air Products and Chemicals Inc. L Albemarle Corp. Lam Research Corp. Alco Standard Fdn Lamson & Sessions Co. Alexander & Baldwin Inc. LandAmerica Financial Group Inc. Alexander Haas Martin & Partners Leo Burnett Co. Inc. Allegiance Corp. and Baxter International Levi Strauss & Co. Allegro MicroSystems W.G. Inc. LEXIS-NEXIS Allendale Mutual Insurance Co. Lexmark Internaional Inc. Alliance Capital Management, LP Thomas J. Lipton Co. Alliant Techsystems Liz Claiborne Inc. AlliedSignal Inc. Loews Corp. American Express Co. Lorillard Tobacco Co. American General Corp. Lotus Development Corp. American Honda Motor Co. Inc. Lubrizol Corp. American Inter Group Lucent Technologies American International Group Inc. American National Bank & Trust Co. of Chicago M American Stock Exchange Maclean-Fogg Co. Ameritech Corp. Maguire Oil Co. Amgen In c. Mallinckrodt Group Inc. AmSouth BanCorp. Foundation Management Compensation AMSTED Industries Inc. Group/Dulworth Inc. Analog Devices Inc. Maritz Inc. Anchor/Russell Capital Advisors Inc. Massachusetts Mutual Life Andersons Inc. Massachusetts Financial Services Investment Aon Corp. Management Archer Daniels Midland Massachusetts Port Authority ARCO MassMutual-Blue Chip Co. -

73 Custer, Wash., 9(1)

Custer: The Life of General George Armstrong the Last Decades of the Eighteenth Daily Life on the Nineteenth-Century Custer, by Jay Monaghan, review, Century, 66(1):36-37; rev. of Voyages American Frontier, by Mary Ellen 52(2):73 and Adventures of La Pérouse, 62(1):35 Jones, review, 91(1):48-49 Custer, Wash., 9(1):62 Cutter, Kirtland Kelsey, 86(4):169, 174-75 Daily News (Tacoma). See Tacoma Daily News Custer County (Idaho), 31(2):203-204, Cutting, George, 68(4):180-82 Daily Olympian (Wash. Terr.). See Olympia 47(3):80 Cutts, William, 64(1):15-17 Daily Olympian Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian A Cycle of the West, by John G. Neihardt, Daily Pacific Tribune (Olympia). See Olympia Manifesto, by Vine Deloria, Jr., essay review, 40(4):342 Daily Pacific Tribune review, 61(3):162-64 Cyrus Walker (tugboat), 5(1):28, 42(4):304- dairy industry, 49(2):77-81, 87(3):130, 133, Custer Lives! by James Patrick Dowd, review, 306, 312-13 135-36 74(2):93 Daisy, Tyrone J., 103(2):61-63 The Custer Semi-Centennial Ceremonies, Daisy, Wash., 22(3):181 1876-1926, by A. B. Ostrander et al., Dakota (ship), 64(1):8-9, 11 18(2):149 D Dakota Territory, 44(2):81, 56(3):114-24, Custer’s Gold: The United States Cavalry 60(3):145-53 Expedition of 1874, by Donald Jackson, D. B. Cooper: The Real McCoy, by Bernie Dakota Territory, 1861-1889: A Study of review, 57(4):191 Rhodes, with Russell P. -

North South East West

1 Port Angeles Visitor Center Olympic Discovery Trail (Hike/Bike) U.S. Coast Guard M.V.Coho Air Station Ferry Dock 2 Ferry Terminal City Park RESTRICTED AREA City Pier School 3 City Pier Pilot Boat VISITOR Bus Transfer Station Station CENTER 4 Arthur Feiro Marine Life Center B Ediz Hook V (Gateway Center) RAILR 5 Post Office RY OAD Hollywood Beach FRONT 6 Clallam County Court House MARINE DRIVE CHER B HWY 101 W FIRST 7 Vern Burton Community Center/City Hall U Victoria 8 North Olympic Library Fountain HWY 101 E 2nd Ferry to 9 Port Angeles Fine Arts Center Y 3rd (HWY 101) 10 Community Players Theater RY VALLE 11 Peninsula College K Y 4th W E CHER OA 12 National Park Visitors Center LINCOLN LAUREL S PEABOD 13 National Park Administration Free 2- and 3-hour parking Chamber of Commerce 14 Clallam County Fairgrounds 121 East Railroad • Port Angeles, WA 98362 Pay Lots 15 Port Angeles Boat Haven (Marina) 360-452-2363 • Fax 360-457-5380 Public Restrooms www.portangeles.org • [email protected] 16 Senior Center S W 4th ST Marina T HILL 2 S 15 W 5th ST 3 T AN very ra isco il to CT W mpic D Se EV S ly q 1 E BAY ST O uim T REET E Y 3rd AV W N W 6th ST MARINE DRIVE RAILRO 4 ALKER U STREET E BAY ST ESTE FRONT AD O W 8th ST L M ST M NELSON A WA 4th AVE TER ST E B DEFRANG N STREET FIRST B S W 4th ST VIEW DR STREET 3rd ST C COL FLORES T UMBIA K N LEE’S CREEK RD 11th ST S HARBOR CREST HARBOR BEECH WA WHITLEY WHITLEY 5th AVE E HAMI 9th ST I STREET STREET 2nd ST BROOK DUNKER LTO Hospital N GALES ST SEABREEZE W N H 4th ST CAROLINE P W 6th ST 3rd ST N BAKER -

A Abbott Laboratories Fund ACE INA/ACE Foundation Matching Gift

A Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Abbott Laboratories Fund Black & Decker Corp. ACE INA/ACE Foundation Matching Gift Blount, Inc. Oregon Cutting Systems Program BNSF Railway Adidas America Boeing Company Adobe Systems Inc. BP (British Petroleum) Aetna Bressie Electric AgriSense Bristol-Myers Squibb AIG Brooks Resources Corp. Akzo Nobel Burlington Northern Santa Fe Company Alaska Tanker Company Butler Manufacturing Co. Alberton’s Alcatel-Lucent C Aldrich Kilbride & Tatone LLP Cadence Design Systems, Inc. AllianceBernstein Callaway Golf Company Allstate Insurance Company Calpine Altria Group, Inc. CAN Foundation American Express Co. Canby Telephone Association American Honda Motor Co., Inc. Capital Group Companies American Property Management Cardinal Health Ameriprise Financial CarMax Amgen Carnegie Foundation AMSTED Industries Caterpillar, Inc. Analog Devices, Inc. Charles Schwab and Company, Inc Anthro Corporation Chevron Corporation Aon Corporation/Aon Risk Services Chubb and Sons, Inc. Applied Materials CIGNA Corporation Archer-Daniels-Midland Cisco Argonaut Group, Inc. Climax Portable Machine Tools, Inc. Arkema Group Clorox Associated Chemists, Inc. CNA Insurance AT&T Coates Kokes Autodesk, Inc. Coca-Cola Company Automatic Data Processing, Inc Columbia Sportswear Company Avon Products Cooper Industries AXA Financial Corning, Inc. Costco Wholesale B Countrywide Backer Capital Management Crown Pacific Inland Sales Bank of America Bank of the West D Barclays Global Investors Davidson Companies Baxter International, Inc. Deluxe Corporation BCD Travel Deutsche Bank Americas Becton Dickinson Dow AgroSciences, LLC Becker Capital Management, Inc. Dow Corning Corp. Bemis Co., Inc. Duke Energy Benjamin Moore & Co E Hanna Andersson/Hanna-Anderson Ease Software, Inc. Foundation Eaton Corporation Hewlett-Packard eBay, Inc. Homestead Capital Ecolab, Inc. Hood River Distillers Eisai Houghton Mifflin Co./Houghton Mifflin Matching Electronic Arts Gifts Elephants Eye Antiques HSBC Eli Lilly and Company Huron Consulting Services Equifax, Inc. -

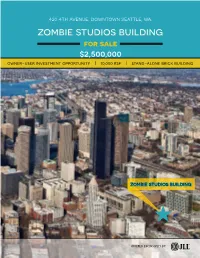

Zombie Studios Building for Sale $2,500,000 Owner-User Investment Opportunity | 10,000 Rsf | Stand-Alone Brick Building

420 4th avenue, downtown seattle, wa. zombie studios building for sale $2,500,000 owner-user investment opportunity | 10,000 rsf | stand-alone brick building zombie studios building OFFERED EXCLUSIVELY BY: BUILDING INFORMATION BUILDING HIGHLIGHTS • Located at the corner of 4th Ave ADDRESS 420 4TH AVENUE, SEATTLE, WA and Jefferson Street SQUARE FEET 10,000 • Excellent freeway access • New roof and HVAC NUMBER OF FLOORS THREE • CAT5 and upgraded electrical BUILT/RENOVATED 1924/2003 • Shower and lockers • Secured building BUILDING TYPE STAND-ALONE BRICK BUILDING • Great location with numerous PARCEL NUMBER 094200-1095 amenities close-by ZONING DMC 340/290-400 w NEIGHBORHOOD Tech companies are drawn to the Pioneer Square area by the neighborhood’s character and proximity to the King Street mass transit hub and area freeways. Over the past few years, numerous public and private projects that include the demolition of the Alaskan Way Viaduct, the restoration of the Elliott Bay seawall, and the redevelopment of the Pike Place Market waterfront entrance -- will offer greater access to the water and enhance the area as a destination. LOCATION 2 4 7 7 BLOCKS BLOCKS BLOCKS BLOCKS to I-5 to King Street Station with rail, to CenturyLink Field to the Ferry Terminal light rail, & bus tunnel access at Coleman Dock SEATTLE AND THE PUGET SOUND Metro Seattle is the commercial, cultural, and advanced technology hub of the Pacific Northwest. A diversified economic base of high tech companies ranging from gaming and software to biotechnology, manufacturing and aerospace technology generates the demand for space in the Puget Sound Region. -

A Chronological History Oe Seattle from 1850 to 1897

A CHRONOLOGICAL HISTORY OE SEATTLE FROM 1850 TO 1897 PREPARED IN 1900 AND 1901 BT THOMAS W. PROSCH * * * tlBLS OF COIfJI'tS mm FAOE M*E PASS Prior to 1350 1 1875 225 1850 17 1874 251 1351 22 1875 254 1852 27 1S76 259 1855 58 1877 245 1854 47 1878 251 1SSS 65 1879 256 1356 77 1830 262 1357 87 1831 270 1358 95 1882 278 1859 105 1383 295 1360 112 1884 508 1861 121 1385 520 1862 i52 1886 5S5 1865 153 1887 542 1364 147 1888 551 1365 153 1883 562 1366 168 1390 577 1867 178 1391 595 1368 186 1892 407 1369 192 1805 424 1370 193 1894 441 1871 207 1895 457 1872 214 1896 474 Apostolus Valerianus, a Greek navigator in tho service of the Viceroy of Mexico, is supposed in 1592, to have discov ered and sailed through the Strait of Fuca, Gulf of Georgia, and into the Pacific Ocean north of Vancouver1 s Island. He was known by the name of Juan de Fuca, and the name was subsequently given to a portion of the waters he discovered. As far as known he made no official report of his discoveries, but he told navi gators, and from these men has descended to us the knowledge thereof. Richard Hakluyt, in 1600, gave some account of Fuca and his voyages and discoveries. Michael Locke, in 1625, pub lished the following statement in England. "I met in Venice in 1596 an old Greek mariner called Juan de Fuca, but whose real name was Apostolus Valerianus, who detailed that in 1592 he sailed in a small caravel from Mexico in the service of Spain along the coast of Mexico and California, until he came to the latitude of 47 degrees, and there finding the land trended north and northeast, and also east and south east, with a broad inlet of seas between 47 and 48 degrees of latitude, he entered therein, sailing more than twenty days, and at the entrance of said strait there is on the northwest coast thereto a great headland or island, with an exceeding high pinacle or spiral rock, like a pillar thereon." Fuca also reported find ing various inlets and divers islands; describes the natives as dressed in skins, and as being so hostile that he was glad to get away. -

Giving Foster Kids a Childhood and a Future

Treehouse gratefully acknowledges the generosity of all our Platt LeRoss Family Foundation • Jill Marsden and Ros Bond • Susan and Matt Maury • Glen Milliman and Alison Wyckoff-Milliman • Netmotion Wireless Marvin Scott • Seattle Rotary Service Foundation • Cynthia Simchuk • Michael Slade • Jerry and Laura Slater • Robert H. Smith • James and Burnley Snyder donors – individuals, foundations and corporations – Jeannie and Bruce Nordstrom • Northern Trust • NW Washington Association Of Health Underwriters • Thomas and Kristin Ogren • Janice and Brian Tad and Jeanne Sommerville • Mark Spain • Sprague Israel Giles, Inc. • Stanton & Everybody, Inc. • Tamara and Gregg Steeb • Sheri Stewart • Leigh Orrico • Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America • Jeanne Quinton • Ragen MacKenzie, Seattle • Shelly Brown Reiss and Michael Stokes • Kara and Don Stout • Elizabeth Strathy and Nick Merrill • Mark and Patti Streissguth • Fayette Stross • Sophie Sussman • Franciene Sznewajs for their gifts in fiscal year 2008. Reiss • Jack and Janice Sabin • Safeco Insurance - Employee Giving Programs • Sealy, Inc. • Seattle Mariners • Ann Simons • Greg and Mimi The Capital Group Companies Charitable Foundation • The Melody S. Robidoux Foundation • The Oki Foundation • Mikal and Lynn Thomsen • Mark Blake and Slyngstad • Starbucks Matching Gifts Program • State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Company • Sterling Realty Organization • The Auld Foundation Katherine Tilley • Todd Meyers Communication • Tommy Bahama • Ed Torkelson • Ann Trapp • TuTu Time • -

90 Pacific Northwest Quarterly Cuthbert, Herbert

Cuthbert, Herbert (Portland Chamber of in Washington,” 61(2):65-71; rev. of Dale, J. B., 18(1):62-65 Commerce), 64(1):25-26 Norwegian-American Studies, Vol. 26, Daley, Elisha B., 28(2):150 Cuthbert, Herbert (Victoria, B.C., alderman), 67(1):41-42 Daley, Heber C., 28(2):150 103(2):71 Dahlin, Ebba, French and German Public Daley, James, 28(2):150 Cuthbertson, Stuart, comp., A Preliminary Opinion on Declared War Aims, 1914- Daley, Shawn, rev. of Atkinson: Pioneer Bibliography of the American Fur Trade, 1918, 24(4):304-305; rev. of Canada’s Oregon Educator, 103(4):200-201 review, 31(4):463-64 Great Highway, 16(3):228-29; rev. Daley, Thomas J., 28(2):150 Cuthill, Mary-Catherine, ed., Overland of The Emigrants’ Guide to Oregon Dalkena, Wash., 9(2):107 Passages: A Guide to Overland and California, 24(3):232-33; rev. of Dall, William Healey, 77(3):82-83, 90, Documents in the Oregon Historical Granville Stuart: Forty Years on the 86(2):73, 79-80 Society, review, 85(2):77 Frontier, Vols. 1 and 2, 17(3):230; rev. works of: Spencer Fullerton Baird: A Cutler, Lyman A., 2(4):293, 23(2):136-37, of The Growth of the United States, Biography, review, 7(2):171 23(3):196, 62(2):62 17(1):68-69; rev. of Hall J. Kelley D’Allair (North West Company employee), Cutler, Thomas R., 57(3):101, 103 on Oregon, 24(3):232-33; rev. of 19(4):250-70 Cutright, Paul Russell, Elliott Coues: History of America, 17(1):68-69; rev. -

Profile/Jerome L. Hillis

Jerome L. Hillis [email protected] direct: 206.470.7601 fax: 206.623.7789 Professional Overview Jerry is a founding member of the firm. His practice focuses on real estate, land use, and environmental law matters. Representative Matters Represented community groups before the State Supreme Court in two cases which established the Appearance of Fairness doctrine in the United States. See Smith v. Skagit County and Chrobuck v. Snohomish County. Coordinated real estate and land use issues involving numerous large development projects, including: Cornerstone Development, Harbor Steps, Washington State Convention Center, Pacific Place/Nordstrom redevelopment, Seattle Mariners' SAFECO Field, Weyerhaeuser's Snoqualmie Ridge Development, and the Klahanie Master Plan Development. Represented Weyerhaeuser Company in the annexation of its headquarters to the City of Federal Way and development of the Master Plan for the headquarters property. Represented PACCAR in development of its Renton facilities, and truck testing facilities in Skagit County. Represented numerous municipalities and government agencies in real estate and land use matters, including City of Bellevue in its acquisition of property for Bellevue Central Park, Port of Seattle in its acquisition of the waterfront property for the Central Waterfront Development, the City of Seattle in its acquisition of the Central Waterfront Piers, and the University of Washington in its development of a Master Plan and negotiations with Sound Transit. Serves as counsel to a wide variety of small to large residential and commercial developers throughout Puget Sound. Articles and Presentations Co-Author, “Seattle City Council Should Revisit Seattle Children’s Expansion Plans,” The Seattle Times, November 6, 2009.