THE RITUAL FESTIVAL of the MEITEIS with REFERENCE to LAI HARAOBA Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(L) N. Tomba Singh Mayang Imphal Konchak Mayai Leikai

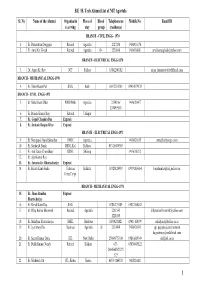

Mayang Imphal A/C Sl No. Card no. Name of Pensioner Address 283 376 /10/MIMP Ningthoujam Shakhen Singh s/o (L) N. Tomba Singh Mayang Imphal konchak Mayai leikai 284 377 /10/MIMP Heisanma Ibecha Devi w/o (L) H. Munal Singh Mayang Imphal konchak Mayai leikai 285 378 /10/MIMP Soibam Mera Devi w/o (L) S. Shitol Singh Mayang Imphal Konchak Mamang leikai 286 379 /10/MIMP Oinam Kuper Singh s/o (L) O. Ibohal Singh Mayang Imphal Konchak Heigum Yangbi 287 380 /10/MIMP Chirom Itocha Devi w/o (L) Ch. Naba Singh Mayang Imphal Konchak Mamang leikai 288 381 /10/MIMP Yumnam Roso Singh s/o (L) Y. Achou Singh Mayang Imphal Anilongbi 289 382 /10/MIMP Laishram Ibopishak Singh s/o (L) L. Yaima Singh Mayang Imphal Anilongbi 290 383 /10/MIMP Angom Birkumar Singh s/o (L) A. Mangi Singh Phoubakchao Bazar 291 384 /10/MIMP Salam Jadumani Singh s/o S. Tombi Singh Tera Hiyangkhong 292 385 /10/MIMP Ningthoujam Ibecha Devi w/o (L) N. Khoimu Laphupat Tera Mayai Leikai 293 386 /10/MIMP Ningthoujam Ibemhal Devi w/o (L) N. Khomei Singh Laphupat Tera Khunou 294 387 /10/MIMP Salam Ibohal Singh s/o (L)S.Gulamjat Singh Laphupat Tera Khordak 295 388 /10/MIMP Thongam Naba Singh s/o (L) Th.Sajoubi Singh Hayel 296 389 /10/MIMP Nongmaithem Ibemhal Devi w/o N. Khomei Singh Mayang Imphal konchak Mayai leikai 297 390 /10/MIMP Sorokhaibam Yaipha Devi w/o (L) S. Kodom Singh Mayang Imphal Thana Khunou 298 391 /10/MIMP Thounaojam Rashamani Devi w/o Th. -

JNEIC Volume 4, Number 2, 2019 | 58 the Dilemma of the Bishnupriya

The Dilemma of the Bishnupriya Identity Naorem Ranjita* Abstract Ethnic identity is a dynamic, multidimensional construct that refers to one's identity, or sense of self, as a member of an ethnic group. The reconstruction of an identity interacts with historical and social identities in the contemporary world. What is intend to discuss in this article is the reconstruction of the Bishnupriya identity in Manipur, and study it against the Bishnupriyas living outside Manipur. The Bishnupriyas remaining in Manipur prefer to be identified as 'Manipuri Meiteis' rather than Bishnupriyas and the logic for this is presumably the perceptions of Bishnupriyas as migrants by the Meiteis. On the other hand, the Bishnupriyas living beyond Manipur, namely in Tripura, Assam, and parts of Bangladesh, would rather be identified as 'Bishnupriya Manipuris', as an attempt to link their identity with the people of Manipur. An observation throughout this paper leads us to reflect upon what the assertion by the Bishnupriyas that 'they' (the Bishnupriyas) are the 'first cultural race' or the 'first settlers' of Manipur and that the Meiteis to be the 'next immigrants'. This speculation has created much doubt and conflict between the Meiteis and the Bishnupriyas. KEYWORDS: Bishnupriya, Meiteis, Manipur Introduction 'The North Eastern part of India is referred to as a melting pot of Mongoloid, Australoid, and Caucasoid populations, which is exhibited in the unique socio-cultural diversity of the region’ (Langstieh et al., 2004: 570). Given the hypothesis that Northeast India is the meeting ground of many diverse culture and population of ethnic and distinctive communities, each unique in its tradition, culture, dress and exotic ways of life, it is evident that migration of people has taken place in different directions. -

The Emergence of Gaudiya Vaishnavism in Manipur and Its Impact on Nat Sankirtana

ISSN (Online): 2350-0530 International Journal of Research -GRANTHAALAYAH ISSN (Print): 2394-3629 July 2020, Vol 8(07), 130 – 136 DOI: https://doi.org/10.29121/granthaalayah.v8.i7.2020.620 THE EMERGENCE OF GAUDIYA VAISHNAVISM IN MANIPUR AND ITS IMPACT ON NAT SANKIRTANA Subhendu Manna *1 *1 Guest Assistant Professor, Rajiv Gandhi University DOI: https://doi.org/10.29121/granthaalayah.v8.i7.2020.620 Article Type: Research Article ABSTRACT The Gaudiya Vaishnavism that emerged with Shri Chaitanya in the Article Citation: Subhendu Manna. fifteenth century continued even after his passing in the hands of his (2020). THE EMERGENCE OF disciples and spread to far-away Manipur. Bhagyachandra – the King of GAUDIYA VAISHNAVISM IN Manipur along with his daughter Bimbabati Devi, visited Nabadwip and MANIPUR AND ITS IMPACT ON NAT SANKIRTANA. International Journal established a temple to Lord Govinda which stands till today in the village of Research -GRANTHAALAYAH, called Manipuri in Nabadwip. Therefore, the strand of Bengal’s Gaudiya 8( ), 130-136. Vaishnavism that Bhagyachandra brought to Manipur continues to flow https://doi.org/10.29121/granthaa through the cultural life of the Manipuri people even today, a prime layah.v8.i7 7.2020.620 example of which is Nat Sankirtana. The influence of Gaudiya Vaishnavism on Nat Sankirtana is unparalleled. Received Date: 02 July 2020 Accepted Date: 27 July 2020 Keywords: Nat Sankirtana Pung Gaudiya Vaishnavism 1. INTRODUCTION The state of Manipur, in the North-Eastern region of India, currently occupies an area of 22,327 square Nagaland, at its south Mizoram. Assam is to its west and Myanmar is to the east. -

Text and Texture of Clothing in Meetei Community: a Contextual Study

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 8 Issue 2, February 2018, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell‟s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A Text and Texture of Clothing in Meetei Community: A Contextual Study Yumnam Sapha Wangam Apanthoi M* Abstract: This paper is an effort to understand Meetei identity through the text and texture of clothing in ritual context. Meeteis are the majority ethnic group of Manipur, who are Mongoloid in origin. According to the Meetei belief system, they consider themselves as the descendents of Lord Pakhangba, the ruling deity of Manipur. Veneration towards Pakhangba and various beliefs and practices related with the Paphal cult have significantly manifested in the cultural and social spheres of Meetei identity. As part of the material culture, dress plays an important role in manifesting the symbolic representation of their relation with Pakhangba in their mundane life. Meetei cloths are deeply embedded with the socio-cultural meaning of the Meeteiness presented in their oral and verbal expressive behaviors. When seven individual groups merged into one community under the political dominance of Mangang/Ningthouja clan, traditional costume became an important agent in order to recognise the individual identity and the common Meetei identity. There are some cloths which have intricate design with various motifs, believed to be derived from the mark of Pakhangba’s body and are used in order to identify the age, sex, social status, and ethnic identity in ritual context. -

Order of Appointment of Presiding and Polling Officers Table

ORDER OF APPOINTMENT OF PRESIDING AND POLLING OFFICERS In pursuance of sub-section(1) and sub-section(3) of section 26 of Representation of the People's Act 1951. I hereby appoint the officers specified in the column no 2 of the table below as presiding officers/polling officers for the Election Duty. PARTY NO : 1 ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY : 9-Thangmeiband TABLE Sl No Name and Mobile No Department Office Designation Appoitnted As 1 CHANDRA SHEKHAR MEENA KENDRA KENDRA PGT HIST PRO 9001986485 VIDYALAYA VIDYALAYA NO 1 LAMPHELPAT 2 KH NABACHNDRA SINGH Education (S) BOARD OF Asst Section Officer PO-I 9436272852 SECONDARY EDUCATION BABUPARA 3 WAIKHOM PRASANTA SINGH Education (S) ZEO ZONE I PRAJA Primary Teacher PO-II 8730872424 UPPER PRIMARY SCHOOL 4 S JITEN SINGH Public Works OFFICE OF EE Road Mohoror PO-III 9612686960 Department HIGHWAYS SOUTH DIV PWD 5 K PEIJAIGAILU KABUINI P.H.E.D. OFFICE OF THE EE Mali PO-IV 0 WATER SUPPLY MAINTENANCE DIV NO I PHED NOTE:(1) The Officers named above shall attend following rehearsals on the date, time and venue mentioned below: Training Date and Time Vanue of Training Reporting Date and Time 04/04/2019 10 Hrs: 00 Min MODEL HR. SEC. SCHOOL (HALL NO. 4) 04/04/2019 : 09 Hrs: 30 Min District Election Officer Imphal West Date: 02/04/2019 14:25:39 Place : Imphal West N.B. Please ensure to bring two recent passport size photographs during training. ORDER OF APPOINTMENT OF PRESIDING AND POLLING OFFICERS In pursuance of sub-section(1) and sub-section(3) of section 26 of Representation of the People's Act 1951. -

B.E / B. Tech Alumni List of NIT Agartala Sl

B.E / B. Tech Alumni List of NIT Agartala Sl. No Name of the Alumni Organisatio Place of Blood Telephone no Mobile No. Email ID n serving stay group (residence) BRANCH - CIVIL ENGG - 1970 1. Er. Purusottam Dasgupta Retired Agartala 2327258 9436916170 2. Er. Amal Kr. Ghosh Retired Agartala O+ 2220540 9436138081 [email protected] BRANCH - ELECTRICAL ENGG-1970 3. Dr. Anjan Kr. Roy NIT Silchar 03842240182 [email protected] BRANCH - MECHANICAL ENGG-1970 4. Er. Timir Baran Pal SAIL Kulti 03412515303 09434579338 BRANCH - CIVIL ENGG-1971 5. Er. Subal Kanti Dhar PWD(PHE) Agartala 2350356/ 9436180477 2354919(O) 6. Er. Pranab Kumar Roy Retired Udaipur 7. Er. Gopal Chandra Das Expired 8. Er. Santosh Ranjan Dhar Expired BRANCH – ELECTRICAL ENGG-1971 9. Er. Nanigopal Gopal Sutradhar ONGC Agartala 9436120115 [email protected] 10. Er. Sankarlal Banik BSNL,Kol Kolkata 033-26630303 11. Er. Asit Baran Chowdhury BSNL Shilong 9436105212 12. Er. Ajit Kumar Roy 13. Er. Jayanta Kr. Bhattacharjee Expired 14. Er. Biresh Kanti Sinha Telecom Kolkata 03325128939 09339204664 bireshsinha@tcil_india.com Const.Corpn. BRANCH - MECHANICAL ENGG-1971 15. Er. Jiban Bandhu Expired Bhattacharjee 16. Er. Bimal Kanti Das SAIL 0788-275289 09827460042 17. Er. Dilip Kumar Bhowmik Retired Agartala 2201545 [email protected] 2221835 18. Er. Sukalyan Bhattacharjee BHEL Haridwar 01334232821 09411100199 [email protected] 19. Er. Jyotirmoy Das Business Agartala B+ 2330444 9436120345 [email protected] [email protected] 20. Er. Samir Kumar Datta EIL New Delhi 25089175/330 09818669349 [email protected] 21. Er. Pulak Kumar Nandy Retired Kolkata 033- 09830405822 26645680/25221 523 22. -

The Following Are the List of Advocates Who Have Exercised Their Option To

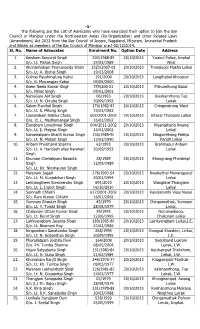

-1- The following are the List of Advocates who have exercised their option to join the Bar Council of Manipur under the Northeastern Areas (Re-Organization) and other Related Laws (Amendment) Act 2012 from the Bar Council of Assam, Nagaland, Mizoram, Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim as members of the Bar Council of Manipur w.e.f-02/12/2014. Sl. No. Name of Advocates Enrolment No. Option Date Address 1. Keisham Somorjit Singh 203/1988 -89 20/10/2013 Yaiskul Police, Imphal S/o. Lt. Pishak Singh 23/03/1989 West 2. Ahongshabam Premananda Singh 1523/2007 -08 20/10/2013 Tronglaobi Makha Leikai S/o. Lt. A. Ibohal Singh 19/03/2008 3. Golmei Paushinglung Kabui 191/2000 20/10/2013 Langthabal Khoupum S/o. G. Moirangjao Kabui 09/05/2000 4. Asem Neela Kumar Singh 759/200 -01 20/10/2013 Pishumthong Bazar S/o. Nimai Singh 09/01/2001 5. Namoijam Ajit Singh 06/1993 20/10/2013 Keishamthong Top S/o. Lt. N. Chroba Singh 30/09/1993 Leirak 6. Salam M anihal Singh 176/1982 -83 20/10/2013 Chingmeirong West S/o. Lt. S. Mitong Singh 15/03/1983 7. Lourembam Rebika Chanu 603/2001 -2002 20/10/2013 Khurai Thongam Leikai D/o. Lt. L. Madhumangal Singh 16/01/2002 8. Elangbam Lokeshwar Singh 604/2011 -2002 20/10/2013 Hiyangthang Awang S/o. Lt. E. Maipak Singh 16/01/2002 Leikai 9. Nameirakpam Shanti Kumar Singh 156/1989 -90 20/10/2013 Ningomthong Pebiya S/o. Lt. N. Mohan Singh 12/03/1990 Pandit Leikai 10. -

Nature Worship

© IJCIRAS | ISSN (O) - 2581-5334 March 2019 | Vol. 1 Issue. 10 NATURE WORSHIP haobam bidyarani devi international girl's hostel, manipur university, imphal, india benevolent and malevolent spirits who had to be Abstract appeased through various forms of sacrifice. Nature Worship Haobam Bidyarani Devi, Ph.D. Student, Dpmt. Of History, Manipur University Keyword: Ancestors, Communities, Nature, Abstract: Manipur is a tiny state of the North East Offerings, Sacrifices, Souls, Spiritual, Supreme Being, region of India with its capital in the city of Imphal. Worshiped. About 90% of the land is mountainous. It is a state 1.INTRODUCTION inhabited by different communities. While the tribals are concentrated in the hill areas, the valley Manipur is a tiny state of the North East region of India of Imphal is predominantly inhabited by the Meiteis, with its capital in the city of Imphal. About 90% of the followed by the Meitei Pangals (Muslim), Non land is mountainous. It is a state inhabited by different Manipuris and a sizable proportion of the tribals. communities. While the tribals are concentrated in the During the reign of Garibniwaz in the late 18th hill areas, the valley of Imphal is predominantly century, the process of Sanskritisation occurred in inhabited by the Meiteis, followed by the Meitei Pangals the valley and the Meitei population converted en (Muslim), Non Manipuris and a sizable proportion of the masse to Hinduism. The present paper is primarily tribals. During the reign of Garibniwaz in the late 18th focused on Nature worship and animism, belief and century, the process of Sanskritisation occurred in the sacrifices performed by the various ethnic groups in valley and the Meitei population converted en masse to Manipur. -

History of North East India (1228 to 1947)

HISTORY OF NORTH EAST INDIA (1228 TO 1947) BA [History] First Year RAJIV GANDHI UNIVERSITY Arunachal Pradesh, INDIA - 791 112 BOARD OF STUDIES 1. Dr. A R Parhi, Head Chairman Department of English Rajiv Gandhi University 2. ************* Member 3. **************** Member 4. Dr. Ashan Riddi, Director, IDE Member Secretary Copyright © Reserved, 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form or by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Publisher. “Information contained in this book has been published by Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, IDE—Rajiv Gandhi University, the publishers and its Authors shall be in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use” Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT LTD E-28, Sector-8, Noida - 201301 (UP) Phone: 0120-4078900 Fax: 0120-4078999 Regd. Office: 7361, Ravindra Mansion, Ram Nagar, New Delhi – 110 055 Website: www.vikaspublishing.com Email: [email protected] About the University Rajiv Gandhi University (formerly Arunachal University) is a premier institution for higher education in the state of Arunachal Pradesh and has completed twenty-five years of its existence. -

Towards the Understanding of Surnames and Naming Patterns in Meitei Society

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 22, Issue 11, Ver. 1 (November. 2017) PP 35-43 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Towards the understanding of surnames and naming patterns in Meitei society Bobita Sarangthem, Centre for Endangered Languages, Tezpur University, Assam India, [email protected] ABSTRACT: Meiteis are the major ethnic group in Manipur, a North East Indian state. Surnames came into existence before king Loiyumpa (1074-1122 AD). Surname is part of a personal name that is passed from either or both parents to their offspring. Surnames in Meitei society are derived from father‟s name. Meiteis have 7 clans and each clan has several surnames. In the 14th century A.D during the reign of King Kiyamba, Brahmins from the mainland of India started to come and settled in Manipur. They have been given different surnames except the seven clans. Again, during the reign of King Khagemba, in the 16th century, Muslims from Bengal started to settle at Manipur, known as Pangal [paŋəl]. These people are now known by the name Meitei pangal. They also have been given with different surnames except the seven clans. This paper is an attempt to provide some insights of surnames and naming patterns in Meitei society and their importance in the society. Keywords - Bamon, clan, Meitei, Pangal, surname. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- Date of Submission: 24-10-2017 Date of acceptance: 04-11-2017 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- I. INTRODUCTION 1. Introduction Meitei or Meetei belongs to the Tibeto-Burman family. Meiteis are the major ethnic group in Manipur, a North East Indian state. -

Slno Name Designation 1 S.Nabakishore Singh Assoc.Prof 2 Y.Sobita Devi Asso.Proffessor 3 Kh.Bhumeshwar Singh

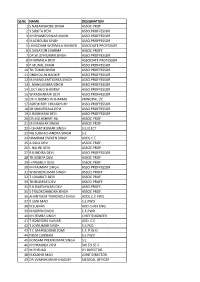

SLNO NAME DESIGNATION 1 S.NABAKISHORE SINGH ASSOC.PROF 2 Y.SOBITA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 3 KH.BHUMESHWAR SINGH. ASSO.PROFFESSOR 4 N.ACHOUBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 5 LUNGCHIM WORMILA HUNGYO ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR 6 K.SANATON SHARMA ASSOC.PROFF 7 DR.W.JOYKUMAR SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 8 N.NIRMALA DEVI ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR 9 P.MUNAL SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 10 TH.TOMBI SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 11 ONKHOLUN HAOKIP ASSO.PROFFESSOR 12 M.MANGLEMTOMBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 13 L.MANGLEMBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 14 LUCY JAJO SHIMRAY ASSO.PROFFESSOR 15 W.RADHARANI DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 16 DR.H.IBOMCHA SHARMA PRINCIPAL I/C 17 ASHOK ROY CHOUDHURY ASSO.PROFFESSOR 18 SH.SHANTIBALA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 19 K.RASHMANI DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 20 DR.MD.ASHRAF ALI ASSOC.PROF 21 M.MANIHAR SINGH ASSOC.PROF. 22 H.SHANTIKUMAR SINGH S.E,ELECT. 23 NG SUBHACHANDRA SINGH S.E. 24 NAMBAM DWIJEN SINGH ADDL.C.E. 25 A.SILLA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 26 L.NALINI DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 27 R.K.INDIRA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 28 TH.SOBITA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 29 H.PREMILA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 30 KH.RAJMANI SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 31 W.BINODKUMAR SINGH ASSCO.PROFF 32 T.LOKABATI DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 33 TH.BINAPATI DEVI ASSCO.PROFF. 34 R.K.RAJESHWARI DEVI ASSO.PROFF., 35 S.TRILOKCHANDRA SINGH ASSOC.PROF. 36 AHANTHEM TOMCHOU SINGH ADDL.C.E.PWD 37 K.SANI MAO S.E.PWD 38 N.SUBHAS ADD.CHIEF ENG. 39 N.NOREN SINGH C.E,PWD 40 KH.TEMBA SINGH CHIEF ENGINEER 41 T.ROBINDRA KUMAR ADD. C.E. -

Global Journal of Human Social Science

Online ISSN: 2249-460X Print ISSN: 0975-587X DOI: 10.17406/GJHSS MalePerceptiononFemaleAttire ConceptofSilkPatternDesign TheSociologicalandCulturalFactors TrainersandtheirGender-Oriented VOLUME18ISSUE2VERSION1.0 Global Journal of Human-Social Science: C Sociology & Culture Global Journal of Human-Social Science: C Sociology & Culture Volume 18 Issue 2 (Ver. 1.0) Open Association of Research Society Global Journals Inc. *OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ (A Delaware USA Incorporation with “Good Standing”; Reg. Number: 0423089) Social Sciences. 2018. Sponsors:Open Association of Research Society Open Scientific Standards $OOULJKWVUHVHUYHG 7KLVLVDVSHFLDOLVVXHSXEOLVKHGLQYHUVLRQ Publisher’s Headquarters office RI³*OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO 6FLHQFHV´%\*OREDO-RXUQDOV,QF Global Journals ® Headquarters $OODUWLFOHVDUHRSHQDFFHVVDUWLFOHVGLVWULEXWHG XQGHU³*OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO 945th Concord Streets, 6FLHQFHV´ Framingham Massachusetts Pin: 01701, 5HDGLQJ/LFHQVHZKLFKSHUPLWVUHVWULFWHGXVH United States of America (QWLUHFRQWHQWVDUHFRS\ULJKWE\RI³*OREDO -RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO6FLHQFHV´XQOHVV USA Toll Free: +001-888-839-7392 RWKHUZLVHQRWHGRQVSHFLILFDUWLFOHV USA Toll Free Fax: +001-888-839-7392 1RSDUWRIWKLVSXEOLFDWLRQPD\EHUHSURGXFHG Offset Typesetting RUWUDQVPLWWHGLQDQ\IRUPRUE\DQ\PHDQV HOHFWURQLFRUPHFKDQLFDOLQFOXGLQJ SKRWRFRS\UHFRUGLQJRUDQ\LQIRUPDWLRQ G lobal Journals Incorporated VWRUDJHDQGUHWULHYDOV\VWHPZLWKRXWZULWWHQ 2nd, Lansdowne, Lansdowne Rd., Croydon-Surrey, SHUPLVVLRQ Pin: CR9 2ER, United Kingdom 7KHRSLQLRQVDQGVWDWHPHQWVPDGHLQWKLV ERRNDUHWKRVHRIWKHDXWKRUVFRQFHUQHG