Meitei Pangal Occupational Shift in History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(L) N. Tomba Singh Mayang Imphal Konchak Mayai Leikai

Mayang Imphal A/C Sl No. Card no. Name of Pensioner Address 283 376 /10/MIMP Ningthoujam Shakhen Singh s/o (L) N. Tomba Singh Mayang Imphal konchak Mayai leikai 284 377 /10/MIMP Heisanma Ibecha Devi w/o (L) H. Munal Singh Mayang Imphal konchak Mayai leikai 285 378 /10/MIMP Soibam Mera Devi w/o (L) S. Shitol Singh Mayang Imphal Konchak Mamang leikai 286 379 /10/MIMP Oinam Kuper Singh s/o (L) O. Ibohal Singh Mayang Imphal Konchak Heigum Yangbi 287 380 /10/MIMP Chirom Itocha Devi w/o (L) Ch. Naba Singh Mayang Imphal Konchak Mamang leikai 288 381 /10/MIMP Yumnam Roso Singh s/o (L) Y. Achou Singh Mayang Imphal Anilongbi 289 382 /10/MIMP Laishram Ibopishak Singh s/o (L) L. Yaima Singh Mayang Imphal Anilongbi 290 383 /10/MIMP Angom Birkumar Singh s/o (L) A. Mangi Singh Phoubakchao Bazar 291 384 /10/MIMP Salam Jadumani Singh s/o S. Tombi Singh Tera Hiyangkhong 292 385 /10/MIMP Ningthoujam Ibecha Devi w/o (L) N. Khoimu Laphupat Tera Mayai Leikai 293 386 /10/MIMP Ningthoujam Ibemhal Devi w/o (L) N. Khomei Singh Laphupat Tera Khunou 294 387 /10/MIMP Salam Ibohal Singh s/o (L)S.Gulamjat Singh Laphupat Tera Khordak 295 388 /10/MIMP Thongam Naba Singh s/o (L) Th.Sajoubi Singh Hayel 296 389 /10/MIMP Nongmaithem Ibemhal Devi w/o N. Khomei Singh Mayang Imphal konchak Mayai leikai 297 390 /10/MIMP Sorokhaibam Yaipha Devi w/o (L) S. Kodom Singh Mayang Imphal Thana Khunou 298 391 /10/MIMP Thounaojam Rashamani Devi w/o Th. -

18 Nov Page 2

Imphal Times Supplementary issue Page No. 2 OF MALE AGGRESSION AND SUPPRESSED VOICES: POETICS OF VIOLENCE IN THE POETRY OF MANIPURI WOMEN AUTHORS By- Linthoingambi Thangjam The northeast region of India is now in Manipur ‘prefer to remain silent for involvement and recognition of [Memchoubi and Chanu, eds., 2003: comprised of eight states namely fear of repercussion in the form of women writers in Manipuri Literature 112]. The addressee is silent in the Assam, Nagaland, Manipur, Tripura, social ostracism, or from shame, and began mostly after the end of the poem, but it is clear that it is one who Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, a plethora of complex emotions and Second World War (1939-45). The is above her. The speaker humbles Meghalaya, and Sikkim. All these feelings’ [ Ibid., 3], holds true. It is dearth in the number of women herself as she conveys how she could states except Sikkim had hitherto been assumed that women in traditional writers before the war, or even meagre only get the flowers that had fallen at independent until their annexation societies in the northeast enjoy percentage after is explained by the the legs of the plants after having into British India in the 19 th Century. greater freedom compared to other prevalent conventional rules and ended their blooming journey. The Sikkim became a part of the Indian societies in India. But, if we look into restrictions placed by Manipuri humbled speaker, throughout the Union in May, 1975. The total these societies as autoethnographers, society on women, and Western poem, repeatedly presents herself as population of all the eight northeast this notion is a misconception not education being strictly discouraged a weak, innocent and submissive states is 3.1 percent of the total only from the politico-historical by ‘amang-asheng’ 1 practices. -

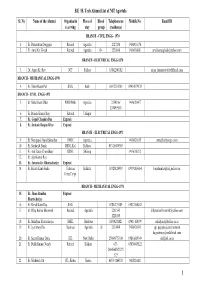

Order of Appointment of Presiding and Polling Officers Table

ORDER OF APPOINTMENT OF PRESIDING AND POLLING OFFICERS In pursuance of sub-section(1) and sub-section(3) of section 26 of Representation of the People's Act 1951. I hereby appoint the officers specified in the column no 2 of the table below as presiding officers/polling officers for the Election Duty. PARTY NO : 1 ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY : 9-Thangmeiband TABLE Sl No Name and Mobile No Department Office Designation Appoitnted As 1 CHANDRA SHEKHAR MEENA KENDRA KENDRA PGT HIST PRO 9001986485 VIDYALAYA VIDYALAYA NO 1 LAMPHELPAT 2 KH NABACHNDRA SINGH Education (S) BOARD OF Asst Section Officer PO-I 9436272852 SECONDARY EDUCATION BABUPARA 3 WAIKHOM PRASANTA SINGH Education (S) ZEO ZONE I PRAJA Primary Teacher PO-II 8730872424 UPPER PRIMARY SCHOOL 4 S JITEN SINGH Public Works OFFICE OF EE Road Mohoror PO-III 9612686960 Department HIGHWAYS SOUTH DIV PWD 5 K PEIJAIGAILU KABUINI P.H.E.D. OFFICE OF THE EE Mali PO-IV 0 WATER SUPPLY MAINTENANCE DIV NO I PHED NOTE:(1) The Officers named above shall attend following rehearsals on the date, time and venue mentioned below: Training Date and Time Vanue of Training Reporting Date and Time 04/04/2019 10 Hrs: 00 Min MODEL HR. SEC. SCHOOL (HALL NO. 4) 04/04/2019 : 09 Hrs: 30 Min District Election Officer Imphal West Date: 02/04/2019 14:25:39 Place : Imphal West N.B. Please ensure to bring two recent passport size photographs during training. ORDER OF APPOINTMENT OF PRESIDING AND POLLING OFFICERS In pursuance of sub-section(1) and sub-section(3) of section 26 of Representation of the People's Act 1951. -

Download Free Study Material & PYQ from Edumo.In

www.edumo.in Combined Higher Secondary Level Examination 2020 (Tier-l) Roll Number Venue Name Siddhi Vinayak Online Examination Center Exam Date 05/08/2021 Exam Time 12:00 PM - 1:00 PM Subject Combined Higher Secondary Level Exam 2020 Section : English Language Q.1 Select the most appropriate option to substitute the underlined segment in the given sentence. If there is no need to substitute it, select ‘No substitution required’. What are the options available of me for a change of career? Ans 1. options available over me 2. options available from me 3. options available to me 4. No substitution required Question ID : 6549786134 Status : Answered Chosen Option : 3 Q.2 Select the option that can be used as a one-word substitute for the given group of words. Instrument that measures the altitude of the land surface Ans 1. Altimeter 2. Thermometer 3. Barometer 4. Chronometer Question ID : 6549786142 Status : Answered Chosen Option : 1 Q.3 Select the most appropriate option to substitute the underlined segment in the given sentence. If there is no need to substitute it, select ‘No substitution required’. If the box breaking the glass bottle will be shattered. Ans 1. If the box break 2. If the box breaks 3. If the box broke 4. No substitution required Question ID : 6549786840 Status : Answered Chosen Option : 2 Download Free Study Material & PYQ from edumo.in www.edumo.in Q.4 Sentences of a paragraph are given below in jumbled order. Arrange the sentences in the right order to form a meaningful and coherent paragraph. -

B.E / B. Tech Alumni List of NIT Agartala Sl

B.E / B. Tech Alumni List of NIT Agartala Sl. No Name of the Alumni Organisatio Place of Blood Telephone no Mobile No. Email ID n serving stay group (residence) BRANCH - CIVIL ENGG - 1970 1. Er. Purusottam Dasgupta Retired Agartala 2327258 9436916170 2. Er. Amal Kr. Ghosh Retired Agartala O+ 2220540 9436138081 [email protected] BRANCH - ELECTRICAL ENGG-1970 3. Dr. Anjan Kr. Roy NIT Silchar 03842240182 [email protected] BRANCH - MECHANICAL ENGG-1970 4. Er. Timir Baran Pal SAIL Kulti 03412515303 09434579338 BRANCH - CIVIL ENGG-1971 5. Er. Subal Kanti Dhar PWD(PHE) Agartala 2350356/ 9436180477 2354919(O) 6. Er. Pranab Kumar Roy Retired Udaipur 7. Er. Gopal Chandra Das Expired 8. Er. Santosh Ranjan Dhar Expired BRANCH – ELECTRICAL ENGG-1971 9. Er. Nanigopal Gopal Sutradhar ONGC Agartala 9436120115 [email protected] 10. Er. Sankarlal Banik BSNL,Kol Kolkata 033-26630303 11. Er. Asit Baran Chowdhury BSNL Shilong 9436105212 12. Er. Ajit Kumar Roy 13. Er. Jayanta Kr. Bhattacharjee Expired 14. Er. Biresh Kanti Sinha Telecom Kolkata 03325128939 09339204664 bireshsinha@tcil_india.com Const.Corpn. BRANCH - MECHANICAL ENGG-1971 15. Er. Jiban Bandhu Expired Bhattacharjee 16. Er. Bimal Kanti Das SAIL 0788-275289 09827460042 17. Er. Dilip Kumar Bhowmik Retired Agartala 2201545 [email protected] 2221835 18. Er. Sukalyan Bhattacharjee BHEL Haridwar 01334232821 09411100199 [email protected] 19. Er. Jyotirmoy Das Business Agartala B+ 2330444 9436120345 [email protected] [email protected] 20. Er. Samir Kumar Datta EIL New Delhi 25089175/330 09818669349 [email protected] 21. Er. Pulak Kumar Nandy Retired Kolkata 033- 09830405822 26645680/25221 523 22. -

11 August Page 2

Imphal Times Supplementary issue 2 Editorial Saturday August 11,, 2018 Constitutional development of Manipur in a nutshell By - Rajkumar Maipaksana Repeating history – Will Contd. from yesterday MANIPUR be in the ratio of 30:18:3 respectively Council of Ministers should be made The dejure and defacto with an additional two seats, are responsible in the modern idea and it burnt the state again STAND STILL AGREEMENT constitution of Manipur was the representing the educational and in a responsible form of government. ‘Three words’ which was signed between the NSCN- On the eve of the implementation of Manipur Constitution Act, 1947. It commercial interests. Precisely the The second defect was that whereas the Indian Independence Act the was framed by a Constitution Assembly would consist 53 members the six Ministers were to be elected IM and the then interlocutor of the Government of British Government made advance making Committee popularly called of which 30 members from 30 General by the MLAs, the Chief Minister India Mr. Padmabhaiya killed 21 people and burnt Special preparations in respect of the Constituent Assembly constituencies, 18 members from 18 was to be appointed by the almost all offices of political parties in the state of the native States of India for the consisting of 16 members hill constituencies, 3 members from Maharaja in consultation with the Manipur. It was June 14, 2001, a day after the then transitional period between the representing the people and 3 Mahamaden constituencies, one Ministers. This gave the Maharaja Defence Minister George Fernandes of Samata Party, transfers of power and finalization officials of Manipur. -

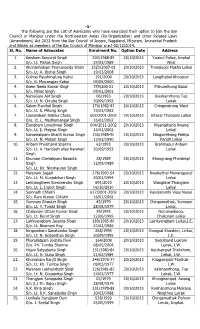

The Following Are the List of Advocates Who Have Exercised Their Option To

-1- The following are the List of Advocates who have exercised their option to join the Bar Council of Manipur under the Northeastern Areas (Re-Organization) and other Related Laws (Amendment) Act 2012 from the Bar Council of Assam, Nagaland, Mizoram, Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim as members of the Bar Council of Manipur w.e.f-02/12/2014. Sl. No. Name of Advocates Enrolment No. Option Date Address 1. Keisham Somorjit Singh 203/1988 -89 20/10/2013 Yaiskul Police, Imphal S/o. Lt. Pishak Singh 23/03/1989 West 2. Ahongshabam Premananda Singh 1523/2007 -08 20/10/2013 Tronglaobi Makha Leikai S/o. Lt. A. Ibohal Singh 19/03/2008 3. Golmei Paushinglung Kabui 191/2000 20/10/2013 Langthabal Khoupum S/o. G. Moirangjao Kabui 09/05/2000 4. Asem Neela Kumar Singh 759/200 -01 20/10/2013 Pishumthong Bazar S/o. Nimai Singh 09/01/2001 5. Namoijam Ajit Singh 06/1993 20/10/2013 Keishamthong Top S/o. Lt. N. Chroba Singh 30/09/1993 Leirak 6. Salam M anihal Singh 176/1982 -83 20/10/2013 Chingmeirong West S/o. Lt. S. Mitong Singh 15/03/1983 7. Lourembam Rebika Chanu 603/2001 -2002 20/10/2013 Khurai Thongam Leikai D/o. Lt. L. Madhumangal Singh 16/01/2002 8. Elangbam Lokeshwar Singh 604/2011 -2002 20/10/2013 Hiyangthang Awang S/o. Lt. E. Maipak Singh 16/01/2002 Leikai 9. Nameirakpam Shanti Kumar Singh 156/1989 -90 20/10/2013 Ningomthong Pebiya S/o. Lt. N. Mohan Singh 12/03/1990 Pandit Leikai 10. -

Review of Judicial Administration of Manipur in Early Period (33-1122 A.D)

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 14, Issue 1 (Jul. - Aug. 2013), PP 15-18 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.Iosrjournals.Org Review of Judicial Administration of Manipur in Early Period (33-1122 A.D) Yumkhaibam Brajakumar Singh Research Scholar, Department of History Manipur University, Imphal Abstract: The present study has been initiated to explore the authoritative accounts of Judicial System of Manipur in early period (33-1122 A.D). As an independent, autonomous and sovereign kingdom, Manipur had distinct system of Judiciary during the period. The findings may also be benefited to the researchers working in the field of anthropology, human geography, politics, law etc. Key Words: Stone Age, Judiciary, Women’s Court, Indian Independence I. Introduction Manipur is the extreme northeastern state of India with a rich cultural heritage. The language, dance, songs, dress, festivals, beliefs, agriculture, administration, and sports have greatly contributed towards Indian culture as a whole. Her unique historical tradition are recorded in the literature, epigraphs and the testimonies of the Greek, Chinese and the Persian travelers and adventures. M. Mc. Culloh was a political Agent of Manipur in two terms during the periods say „1844-1862‟ and „1863-1867‟ during the reign of Meidingu Nara Singh and Meidingu Chandrakirti. He remarked that Manipur had different names to call by different neighboring countries. It is called „Meitheileipak‟ by the Maniporees, the local people of Manipur. The Burmese called it Kathe, the Bengalees, Moglai and the Assamese, Mekle (Pande, 1985). Since the ancient time, Manipur was a trade route. -

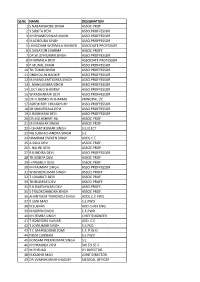

Slno Name Designation 1 S.Nabakishore Singh Assoc.Prof 2 Y.Sobita Devi Asso.Proffessor 3 Kh.Bhumeshwar Singh

SLNO NAME DESIGNATION 1 S.NABAKISHORE SINGH ASSOC.PROF 2 Y.SOBITA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 3 KH.BHUMESHWAR SINGH. ASSO.PROFFESSOR 4 N.ACHOUBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 5 LUNGCHIM WORMILA HUNGYO ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR 6 K.SANATON SHARMA ASSOC.PROFF 7 DR.W.JOYKUMAR SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 8 N.NIRMALA DEVI ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR 9 P.MUNAL SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 10 TH.TOMBI SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 11 ONKHOLUN HAOKIP ASSO.PROFFESSOR 12 M.MANGLEMTOMBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 13 L.MANGLEMBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 14 LUCY JAJO SHIMRAY ASSO.PROFFESSOR 15 W.RADHARANI DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 16 DR.H.IBOMCHA SHARMA PRINCIPAL I/C 17 ASHOK ROY CHOUDHURY ASSO.PROFFESSOR 18 SH.SHANTIBALA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 19 K.RASHMANI DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 20 DR.MD.ASHRAF ALI ASSOC.PROF 21 M.MANIHAR SINGH ASSOC.PROF. 22 H.SHANTIKUMAR SINGH S.E,ELECT. 23 NG SUBHACHANDRA SINGH S.E. 24 NAMBAM DWIJEN SINGH ADDL.C.E. 25 A.SILLA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 26 L.NALINI DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 27 R.K.INDIRA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 28 TH.SOBITA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 29 H.PREMILA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 30 KH.RAJMANI SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 31 W.BINODKUMAR SINGH ASSCO.PROFF 32 T.LOKABATI DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 33 TH.BINAPATI DEVI ASSCO.PROFF. 34 R.K.RAJESHWARI DEVI ASSO.PROFF., 35 S.TRILOKCHANDRA SINGH ASSOC.PROF. 36 AHANTHEM TOMCHOU SINGH ADDL.C.E.PWD 37 K.SANI MAO S.E.PWD 38 N.SUBHAS ADD.CHIEF ENG. 39 N.NOREN SINGH C.E,PWD 40 KH.TEMBA SINGH CHIEF ENGINEER 41 T.ROBINDRA KUMAR ADD. C.E. -

Global Journal of Human Social Science

Online ISSN: 2249-460X Print ISSN: 0975-587X DOI: 10.17406/GJHSS MalePerceptiononFemaleAttire ConceptofSilkPatternDesign TheSociologicalandCulturalFactors TrainersandtheirGender-Oriented VOLUME18ISSUE2VERSION1.0 Global Journal of Human-Social Science: C Sociology & Culture Global Journal of Human-Social Science: C Sociology & Culture Volume 18 Issue 2 (Ver. 1.0) Open Association of Research Society Global Journals Inc. *OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ (A Delaware USA Incorporation with “Good Standing”; Reg. Number: 0423089) Social Sciences. 2018. Sponsors:Open Association of Research Society Open Scientific Standards $OOULJKWVUHVHUYHG 7KLVLVDVSHFLDOLVVXHSXEOLVKHGLQYHUVLRQ Publisher’s Headquarters office RI³*OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO 6FLHQFHV´%\*OREDO-RXUQDOV,QF Global Journals ® Headquarters $OODUWLFOHVDUHRSHQDFFHVVDUWLFOHVGLVWULEXWHG XQGHU³*OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO 945th Concord Streets, 6FLHQFHV´ Framingham Massachusetts Pin: 01701, 5HDGLQJ/LFHQVHZKLFKSHUPLWVUHVWULFWHGXVH United States of America (QWLUHFRQWHQWVDUHFRS\ULJKWE\RI³*OREDO -RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO6FLHQFHV´XQOHVV USA Toll Free: +001-888-839-7392 RWKHUZLVHQRWHGRQVSHFLILFDUWLFOHV USA Toll Free Fax: +001-888-839-7392 1RSDUWRIWKLVSXEOLFDWLRQPD\EHUHSURGXFHG Offset Typesetting RUWUDQVPLWWHGLQDQ\IRUPRUE\DQ\PHDQV HOHFWURQLFRUPHFKDQLFDOLQFOXGLQJ SKRWRFRS\UHFRUGLQJRUDQ\LQIRUPDWLRQ G lobal Journals Incorporated VWRUDJHDQGUHWULHYDOV\VWHPZLWKRXWZULWWHQ 2nd, Lansdowne, Lansdowne Rd., Croydon-Surrey, SHUPLVVLRQ Pin: CR9 2ER, United Kingdom 7KHRSLQLRQVDQGVWDWHPHQWVPDGHLQWKLV ERRNDUHWKRVHRIWKHDXWKRUVFRQFHUQHG -

14 August Page 1

Evening daily Imphal Times Regd.No. MANENG /2013/51092 Volume 6, Issue 197, Tuesday, Aug 14, 2018 www.imphaltimes.com Maliyapham Palcha Kumshing 3416 2/- Manipur’s Independence Day celebrated Arrest VC, AP Pandey and Leishemba Sanajaoba demands resolve MU issue - Sanajaoba IT News government, said the Titular leaders of the Central Imphal, Aug 14, King while addressing the Government, but government pre-merger status for Manipur nd gathering at the 72 could arrest him immediately The Titular King of Manipur, celebration of Manipur to ensure normalcy,” said Leishemba Sanajaoba has Independence Day held at Leishamba, while adding that IT News demanded to arrest the Sanakonung here today even if the people of Manipur Imphal, Aug 14, controversial Vice-Chancellor morning. wanted to arrest the VC or of Manipur, AP Pandey for While questioning the state resolve the ongoing MU Titular King of Manipur, causing social unrest in the government of not arresting issue, the state government Leishemba Sanajaoba has state of Manipur. the VC, Leishemba said that could not to do so because of demanded pre-merger political Due to the ongoing demand law and order is under state the state-centre relationship. status of Manipur, while for removal of the Vice- subject. Any person causing The only solution to long speaking on the 72nd Chancellor of Manipur social turmoil should be lasting solution to all the Manipur’s Independence Day University large number of arrested immediately and problems in Manipur is review celebration at Sanakonung, students are suffering and enquiry could be conducted the Instrument of Accession here in Imphal today. -

MSME) MANIPUR ( EM Part-II Filed As on 2013-2014

DIRECTORY OF MICRO, SMALL & MEDIUM ENTERPRISES (MSME) MANIPUR ( EM Part-II filed as on 2013-2014 ) VOLUME-I Department of Commerce & Industries Government of Manipur Govvindas Konthoujam Minister Commerce & Industries Veterinary & An imal Husban dry and Sericulture Manipur MESSAGE I am happy to learn that the Directorate of Commerce & Industries, Manipur, is publishing a Directory of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs). The importance of a Directory is needless to mention as all the vital information of an enterprise can be known from this Directory easily. The tireless efforts and endeavours rendered by S/Shri M. Lyanchinpao (Statistical Supervisor), N. Rupachandra Singh (Statistical Supervisor), Ch. Khogendra Singh (Statistical Supervisor) and M. Kunjeshwar Meetei (Extension Officer) and RV. John, OSD (Nucleus Cell) under the guidance of Shri B. John Tlangtinkhuma, IAS, Director of Commerce & Industries, Manipur for printing of the Directory is highly appreciated. It may not be out of place to mention that the valuable contribution made by Shri S. Birendra Singh, former Functional Manager (KVI), OSD Handicrafts/Nucleus Cell who took the initial role to publish this Directory, deserves special appreciation from all the hearts involved in the production of such an important Directory. I hope that this Directory will be useful for the Entrepreneurs, Econoomists and Scholars for various purposes as growth of MSMEs, its employment, production, etc. are included in this Directory with graphical presentation and tabulation. I wish the publication all success. (Govindas Konthoujam) Lungmuana Lakher IAS Prrincipal Secretary(C&I) FOREWORD It gives me immense pleasure to learn that the Directorate of Commerce & Industries, Manipur, is bringing out a Directory of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME) for the years 2007-08 to 2013-14.