Nemesis Narratives the Relationship Between Embedded and Emergent Narrative in Middle Earth: Shadow of Mordor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inside the Video Game Industry

Inside the Video Game Industry GameDevelopersTalkAbout theBusinessofPlay Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman Downloaded by [Pennsylvania State University] at 11:09 14 September 2017 First published by Routledge Th ird Avenue, New York, NY and by Routledge Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business © Taylor & Francis Th e right of Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman to be identifi ed as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections and of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act . All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice : Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identifi cation and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Names: Ruggill, Judd Ethan, editor. | McAllister, Ken S., – editor. | Nichols, Randall K., editor. | Kaufman, Ryan, editor. Title: Inside the video game industry : game developers talk about the business of play / edited by Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman. Description: New York : Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa Business, [] | Includes index. Identifi ers: LCCN | ISBN (hardback) | ISBN (pbk.) | ISBN (ebk) Subjects: LCSH: Video games industry. -

2010 Annual Report

2010 Corporate Philosophy To spread happiness across the globe by providing unforgettable experiences This philosophy represents our company’s mission and the beliefs for which we stand. Each of our customers has his or her own definition of happiness. The Square Enix Group provides high-quality content, services, and products to help those customers create their own wonderful, unforgettable experiences, thereby allowing them to discover a happiness all their own. Management Guidelines These guidelines reflect the foundation of principles upon which our corporate philosophy stands, and serve as a standard of value for the Group and its members. We shall strive to achieve our corporate goals while closely considering the following: 1. Professionalism We shall exhibit a high degree of professionalism, ensuring optimum results in the workplace. We shall display initiative, make continued efforts to further develop our expertise, and remain sincere and steadfast in the pursuit of our goals, while ultimately aspiring to forge a corporate culture disciplined by the pride we hold in our work. 2. Creativity and Innovation To attain and maintain new standards of value, there are questions we must ask ourselves: Is this creative? Is this innovative? Mediocre dedication can only result in mediocre achievements. Simply being content with the status quo can only lead to a collapse into oblivion. To prevent this from occurring and to avoid complacency, we must continue asking ourselves the aforementioned questions. 3. Harmony Everything in the world interacts to form a massive system. Nothing can stand alone. Everything functions with an inevitable accord to reason. It is vital to gain a proper understanding of the constantly changing tides, and to take advantage of these variations instead of struggling against them. -

Die Erben Mittelerdes

wissenschaftliche Hausarbeit zur Ersten Staatsprüfung Uwe R. Hoeppe W Die Erben Mittelerdes Zum Einfluss von J.R.R. Tolkiens "Lord of the Rings" auf die fantastische Literatur sowie die Comic- und Spielekultur issenschaftliche Hausarbeit zur Ersten Staatspruefung fuer das Lehramt wissenschaftliche Hausarbeit zur Ersten Staatsprüfung Gewidmet meinen Eltern, die mir das Studium der Anglistik ermöglicht haben. Kassel, Sommer 1999 issenschaftliche Hausarbeit zur Ersten Staatspruefung fuer das Lehramt Uwe R. Hoeppe Die Erben Mittelerdes Inhalt Inhaltsverzeichnis Einleitung.........................................3 Genres.............................................4 Fantasy.................................................4 Comic.................................................11 Spiele.................................................14 Rollenspiele...........................................................15 Trading Card Games...............................................18 Computerspiele......................................................20 Film...................................................22 Analyse..........................................26 Geografie.............................................27 Magie & Macht.......................................33 Gut & Böse...........................................37 Rassen.................................................45 Ainur.....................................................................48 Elves.....................................................................50 Dwarves................................................................57 -

Mordor-Manual

Book IV of The Two Towers Guide to Middle-earth Software Licensing & Marketing Ltd. A ~~ Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc. Reading, Massachusetts New York Menlo Park, California Don Mills, Ontario Wokingham, England Amsterdam Bonn Sydney Singapore Tokyo Madrid San Juan The plot of The Shadows of Mordor, Book IV of The Illustrations by J. R. R. Tolkien: Two Towers, the character of the Hobbit, and other The Mountain-path © George Allen &. Unwin (Pub characters from J. R. R. Tolkien's novel are copyright lishers) Ltd., 1937, 1975, 1977, 1979. The Misty Moun © George Allen &. Unwin Ltd., 1954, 1966. tains looking We st from the Eyrie towards Goblin Gate © George Allen &. Unwin (Publishers) Ltd., The Shadows of Mordor software program is copyright 1937, 1975, 1977, 1979· Orthanc © George Allen &. © 1988 by Beam Software. Unwin (Publishers) Ltd., 1976, 1977, 1979. Patterns (II) © George Allen &. Unwin (Publishers) Ltd., 1978, The Shadows of Mordor Software Adventure and 1979 . Floral DeSigns © George Allen &. Unwin (Pub User's Guide are copyright © 1988 by Addison-Wesley lishers) Ltd., 1978, 1979. Numen6rean Tile and Tex Publishing Company, Inc. tiles © George Allen &. Unwin (Publishers) Ltd., 1973, 1977, 1979· All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmit The Shadows of Mordor software program was a ma ted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechan jor effort by the programming team at Beam Software. ical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without The project took over twelve months to complete. the prior written permission of the Publisher. Project Coordination John Haward Inglish@ is a trademark of Software Licensing &. -

Warnermedia O Home Box Office, Inc

WarnerMedia o Home Box Office, Inc. and family companies including: . HBO Digital Services, Inc. HBO Home Entertainment, Inc. HBO Service Corporation . HBO Retail Ventures, Inc. Europe • HBO Bulgaria EOOD • HBO Adria d.o.o. • HBO Europe s.r.o. • HBO Adria SRB Lt. Belgrade. • HBO Holding Zrt. • HBO Polska Sp. z.o.o. • HBO Romania Srl • HBO poslovne storitve d.o.o. • HBO Code Labs International GmbH. • HBO Europe Original Programming Limited • HBO Nordic Services Denmark APS • HBO Nordic Services Norway AS • HBO Nordic Services Finland Oy • Home Box Office Spain Ventures, S.L. • HBO Nordic AB . Asia • Home Box Office (Taiwan) Co. Ltd. • Home Box Office (Singapore) Pte. Ltd. • Affiliates Asia, L.L.C. • HBO Pacific Partners, V.O.F. Canada • HBO Canada Services, Inc. o Turner Broadcasting System Inc. and family companies including: . Bleacher Report, Inc. Cable News International, Inc. Cable News Network, Inc. Cartoon Interactive Group, Inc. Cartoon Network Enterprises, Inc. Catch Sports LLC . CNE Tours, Inc. (F/K/A Cartoon Network Shop, Inc.) . CNN Interactive Group, Inc. Court TV Digital LLC . Courtroom Television Network LLC . Filmstruck LLC . Great Big Story, LLC . iStreamPlanet Co., LLC . Retro, Inc. Superstation, Inc. TBS Interactive Group, Inc. TCM Interactive Group, Inc. The Cartoon Network, Inc. TNT Interactive Group, Inc. TNT Originals, Inc. Turner Broadcasting Sales, Inc. Turner Classic Movies, Inc. Turner Digital Basketball Services, Inc. Turner Data Solutions, LLC . Super Deluxe, LLC (F/K/A Turner Digital Entertainment, LLC) . Turner Entertainment Networks, Inc. Turner Festivals, Inc. (F/K/A Turner Direct Retailing, Inc.) . Turner Media Ventures, Inc. Turner Network Sales, Inc. -

HOW to PLAY with MAPS by Ross Thorn Department of Geography, UW-Madison a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Require

HOW TO PLAY WITH MAPS by Ross Thorn Department of Geography, UW-Madison A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Geographic Information Science and Cartography) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN–MADISON 2018 i Acknowledgments I have so many people to thank for helping me through the process of creating this thesis and my personal development throughout my time at UW-Madison. First, I would like to thank my advisor Rob Roth for supporting this seemingly crazy project and working with me despite his limited knowledge about games released after 1998. Your words of encouragement and excitement for this project were invaluable to keep this project moving. I also want to thank my ‘second advisor’ Ian Muehlenhaus for not only offering expert guidance in cartography, but also your addictive passion for games and their connection to maps. You provided endless inspiration and this research would not have been possible without your support and enthusiasm. I would like to thank Leanne Abraham and Alicia Iverson for reveling and commiserating with me through the ups and downs of grad school. You both are incredibly inspirational to me and I look forward to seeing the amazing things that you will undoubtedly accomplish in life. I would also like to thank Meghan Kelly, Nick Lally, Daniel Huffman, and Tanya Buckingham for creating a supportive and fun atmosphere in the Cartography Lab. I could not have succeeded without your encouragement and reminder that we all deserve to be here even if we feel inadequate. You made my academic experience unforgettable and I love you all. -

The Shadows of Mordor

The Shadows of Mordor INTRODUCTION Welcome to The Shadows of Mordor, in which Frodo Baggins and Sam Gamgee continue their quest to destroy the power of the evil Dark Lord, Sauron. In playing this adventure game, you will be assuming the role of characters in JRR. Tolkien’s fantasy world. You must detail out the actions which your characters are to perform, and the computer will moderate the results accordingly. It should be noted that there are few if any problems in this game which have a single solution. The game has been designed to allow a variety of responses to the adventure problems, some of which are more efficient than others. The Shadows of Mordor is a brilliant piece of fantasy software thanks to the re- working of many of the games systems by a highly trained team of idiots. The game system will be familiar to players of Lord of the Rings Game One, with the exception of the improvements in the flexibility of play. For instance, it is now possible to talk to characters and give them a string of instructions which they will follow in sequence, rather than painstakingly telling them what to do at each and every turn. In order to provide players with the host of problems expected from a high quality computer adventure, it has been necessary to take minor liberties with Lord of the Rings storyline (it wouldn’t be much of a game if there was no challenge to interrupt the storyline of Tolkien’s master work), and thus we hope that you will see them in the light in which they were intended, and not as blasphemous attempts to butcher one of the great works of fantasy literature. -

Games Overview

Games Overview April 2013 Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment Overview Business Overview Videogame Development • Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment (“WBIE”) is a developer, • WBIE currently operates across videogame development, publisher, licensor and distributor of videogames publishing, licensing and distribution • Offers videogames across console, handheld platforms, social • Grew operations from licensing to publishing through organic networks and mobile growth and notable strategic acquisitions: • WB Games is the production unit of WBIE and was • 1995: Licensed properties for videogame development established in 2007 under the Warner Bros. name • WBIE's videogames are based on newly created IP, IP owned by • 2004: Acquired Monolith Productions (developer) Warner Bros. (“WB”), DC Comics (wholly owned by WB) and third • 2007: Acquired TT Games (developer/publisher) party licensors • 2010: Acquired Turbine (developer/publisher) • FY2012 videogame revenue was $800mm • 2012 videogame releases: $548mm Content Platforms • Prior videogame releases: $203mm Mobile / Online / • Third party distribution: $49mm Console Download Apps Social) MMOGs • WBIE was established in Jan-2004 and is a division of Warner Bros. Home Entertainment Group (“WBHE”) • WBHE operates under Time Warner’s (NYSE: TWX) Film Paid / Paid / Paid Paid / Free Freemium and TV Entertainment reporting segment (FY12 Revenue: Freemium Freemium $12bn), which consists of feature film, TV, home video and videogame production and distribution Source: Company filings, company -

News from Bree

NewsNewsNews fromfromfrom BreeBreeBree MEPBM Newsletter: Issue 29, September'05 "Strange as News from Bree..." Is this the best The Lord of the Rings, chapter 9 1650 character? by Sam “Does Anyone Mind Talk at the If I Retire Elrond?” Roads Is it Fatboy Elrond with his 70/70 vision? Is it Din what Tencom’s other stats are. However, ‘Commander 'Prancing'Prancing “Quick Kill” Ohtar or occasional army commander Tencom’ would very likely to be a 30/0/0/0 character Ji Indur*? Maybe the King of the Nazgul - Mumu? and therefore safe to challenge. If you’re planning on Pony... No, gentle reader, the finest character in 1650 is going down this path to victory, you might want to Pony... from Cardolan and hasn’t been created at the game pass over Tencom as a potential name and try something start. This lady has the following game breaking a little more Cardiff-city-centre-on-Friday-night, like The Best 1650 Character? stats: 10/0/0/0(0) ‘Mauler’, ‘Bloodhowler’ or maybe ‘Clint’. Sam is trying to retire Elrond again ... Whilst an initial comparison between this 10 · Tencom can hire for free. commander and Elrond might lead you to spot the · You will not be petrified of losing Tencom and thus An A-Z of Tolkien slight difference in power levels, there are many issue unneccessary 215 orders whilst ‘at risk’ in the Castamir, Elves, Frodo, things in favour of ‘Tencom’. forests of Mithlond. Gimli & Hobbits · Your teammates will not laugh themselves silly** · Tencom costs 200 gold per turn. -

Middle-Earth: Shadow of Mordor (PS4) Review – Befitting Of

Trending 2D-X Staff » Features » X-Lists How To The Best Damn Video Game Podcast Ever PC Gaming Console Gaming Handheld Gaming Middle-Earth: Shadow of Mordor (PS4) Review POPULAR COMMENTS LATEST – Befitting of Tolkien’s legacy TODAY WEEK MONTH ALL X-List: The 18 best 2D games of the Posted on Oct 30 2014 - 7:35am by Stephanie Burdo Edit HD era X-List: The 10 worst one-liners in video game history X-List: The 7 best 2D PC games X-List: The 13 best PSP games of all time Diablo III: Reaper of Souls - PS4 vs. PC, battle to the bloody death X-List: The 9 best 2D fighting games of all time Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor Epic 4chan Pokemon artwork: Take two Epic 4chan Pokemon artwork: Part one X-List: The 10 Best PS2 games of all time Ask Tatjana: What's it REALLY like to work at GameStop? Anxiety has grown for the long awaited arrival of a game that would set a standard for the future of PlayStation 4 and Xbox One. That game has finally arrived. This entirely new IP is not a remake or a past-gen port, as many current gen titles have been so far. Not only does this new title take “triple A” games to the next level, but it has already overcome what some would call a tremendous feat which is, creating a game that is deserving of classic Tolkien, Middle-earth lore. Many have tried and many have done well, but none have hit such a high pitch as Middle- earth: Shadow of Mordor. -

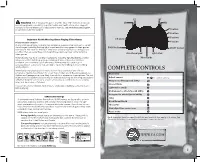

Complete Controls Symptoms

LT RT WARNING Before playing this game, read the Xbox 360® Instruction Manual LB RB and any peripheral manuals for important safety and health information. Keep all manuals for future reference. For replacement manuals, see www.xbox.com/support or call Xbox Customer Support. Y button X button B button Important Health Warning About Playing Video Games left stick A button Photosensitive seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including fl ashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. BACK button START button Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. directional pad right stick These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered Xbox Guide vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these CoMplete Controls symptoms. Parents should watch for or ask their children about the above symptoms— Movement children and teenagers are more likely than adults to experience these seizures. The risk of photosensitive epileptic seizures may be reduced by taking the following precautions: Adjust camera ( to center camera) Sit farther from the screen; use a smaller screen; play in a well-lit room; do not play Weapon modifier/Special ability when you are drowsy or fatigued. -

The Inform Designer's Manual

Cited Works of Interactive Fiction The following bibliography includes only those works cited in the text of this book: it makes no claim to completeness or even balance. An index entry is followed by designer's name, publisher or organisation (if any) and date of first substantial version. The following denote formats: ZM for Z-Machine, L9 for Level 9's A-code, AGT for the Adventure Game Toolkit run-time, TADS for TADS run-time and SA for Scott Adams's format. Games in each of these formats can be played on most modern computers. Scott Adams, ``Quill''-written and Cambridge University games can all be mechanically translated to Inform and then recompiled as ZM. The symbol marks that the game can be downloaded from ftp.gmd.de, though for early games} sometimes only in source code format. Sa1 and Sa2 indicate that a playable demonstration can be found on Infocom's first or second sampler game, each of which is . Most Infocom games are widely available in remarkably inexpensive packages} marketed by Activision. The `Zork' trilogy has often been freely downloadable from Activision web sites to promote the ``Infocom'' brand, as has `Zork: The Undiscovered Underground'. `Abenteuer', 264. German translation of `Advent' by Toni Arnold (1998). ZM } `Acheton', 3, 113 ex8, 348, 353, 399. David Seal, Jonathan Thackray with Jonathan Partington, Cambridge University and later Acornsoft, Topologika (1978--9). `Advent', 2, 47, 48, 62, 75, 86, 95, 99, 102, 105, 113 ex8, 114, 121, 124, 126, 142, 146, 147, 151, 159, 159, 179, 220, 221, 243, 264, 312 ex125, 344, 370, 377, 385, 386, 390, 393, 394, 396, 398, 403, 404, 509 an125.