Leon Russianoff: Clarinet Pedagogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nasher Sculpture Center's Soundings Concert Honoring President John F. Kennedy with New Work by American Composer Steven Macke

Nasher Sculpture Center’s Soundings Concert Honoring President John F. Kennedy with New Work by American Composer Steven Mackey to be Performed at City Performance Hall; Guaranteed Seating with Soundings Season Ticket Package Brentano String Quartet Performance of One Red Rose, co-commissioned by the Nasher with Carnegie Hall and Yellow Barn, moved to accommodate bigger audience. DALLAS, Texas (September 12, 2013) – The Nasher Sculpture Center is pleased to announce that the JFK commemorative Soundings concert will be performed at City Performance Hall. Season tickets to Soundings are now on sale with guaranteed seating to the special concert honoring President Kennedy on the 50th anniversary of his death with an important new work by internationally renowned composer Steven Mackey. One Red Rose is written for the Brentano String Quartet in commemoration of this anniversary, and is commissioned by the Nasher (Dallas, TX) with Carnegie Hall (New York, NY) and Yellow Barn (Putney, VT). The concert will be held on Saturday, November 23, 2013 at 7:30 pm at City Performance Hall with celebrated musicians; the Brentano String Quartet, clarinetist Charles Neidich and pianist Seth Knopp. Mr. Mackey’s One Red Rose will be performed along with seminal works by Olivier Messiaen and John Cage. An encore performance of One Red Rose, will take place Sunday, November 24, 2013 at 2 pm at the Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza. Both concerts will include a discussion with the audience. Season tickets are now available at NasherSculptureCenter.org and individual tickets for the November 23 concert will be available for purchase on October 8, 2013. -

PROGRAM NOTES Wolfgang Mozart Clarinet Concerto in a Major, K

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Wolfgang Mozart Born January 27, 1756, Salzburg, Austria. Died December 5, 1791, Vienna, Austria. Clarinet Concerto in A Major, K. 622 Mozart composed this concerto between the end of September and mid-November 1791, and it apparently was performed in Vienna shortly afterwards. The orchestra consists of two flutes, two bassoons, two horns, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-nine minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first performance of Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto was given at the Ravinia Festival on July 25, 1957, with Reginald Kell as soloist and Georg Solti conducting. The Orchestra’s first subscription concert performance was given at Orchestra Hall on May 2, 1963, with Clark Brody as soloist and Walter Hendl conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on October 11 and 12, 1991, with Larry Combs as soloist and Sir Georg Solti conducting. The Orchestra most recently performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on July 15, 2001, with Larry Combs as soloist and Sir Andrew Davis conducting. This concerto is the last important work Mozart finished before his death. He recorded it in his personal catalog without a date, right after The Magic Flute and La clemenza di Tito. The only later entry is the little Masonic Cantata, dated November 15, 1791. The Requiem, as we know, didn’t make it into the list. For decades the history of the Requiem was full of ambiguity, while that of the Clarinet Concerto seemed quite clear. But in recent years, as we learned more about the unfinished Requiem, questions about the concerto began to emerge. -

June WTTW & WFMT Member Magazine

Air Check Dear Member, The Guide As we approach the end of another busy fiscal year, I would like to take this opportunity to express my The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT heartfelt thanks to all of you, our loyal members of WTTW and WFMT, for making possible all of the quality Renée Crown Public Media Center content we produce and present, across all of our media platforms. If you happen to get an email, letter, 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue or phone call with our fiscal year end appeal, I’ll hope you’ll consider supporting this special initiative at Chicago, Illinois 60625 a very important time. Your continuing support is much appreciated. Main Switchboard This month on WTTW11 and wttw.com, you will find much that will inspire, (773) 583-5000 entertain, and educate. In case you missed our live stream on May 20, you Member and Viewer Services can watch as ten of the area’s most outstanding high school educators (and (773) 509-1111 x 6 one school principal) receive this year’s Golden Apple Awards for Excellence WFMT Radio Networks (773) 279-2000 in Teaching. Enjoy a wide variety of great music content, including a Great Chicago Production Center Performances tribute to folk legend Joan Baez for her 75th birthday; a fond (773) 583-5000 look back at The Kingston Trio with the current members of the group; a 1990 concert from the four icons who make up the country supergroup The Websites wttw.com Highwaymen; a rousing and nostalgic show by local Chicago bands of the wfmt.com 1960s and ’70s, Cornerstones of Rock, taped at WTTW’s Grainger Studio; and a unique and fun performance by The Piano Guys at Red Rocks: A Soundstage President & CEO Special Event. -

Beethoven, Bagels & Banter

Beethoven, Bagels & Banter SUN / OCT 21 / 11:00 AM Michele Zukovsky Robert deMaine CLARINET CELLO Robert Davidovici Kevin Fitz-Gerald VIOLIN PIANO There will be no intermission. Please join us after the performance for refreshments and a conversation with the performers. PROGRAM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Trio in B-flat major, Op. 11 I. Allegro con brio II. Adagio III. Tema: Pria ch’io l’impegno. Allegretto Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) Quartet for the End of Time (1941) I. Liturgie de cristal (“Crystal liturgy”) II. Vocalise, pour l'Ange qui annonce la fin du Temps (“Vocalise, for the Angel who announces the end of time”) III. Abîme des oiseau (“Abyss of birds”) IV. Intermède (“Interlude”) V. Louange à l'Éternité de Jésus (“Praise to the eternity of Jesus”) VI. Danse de la fureur, pour les sept trompettes (“Dance of fury, for the seven trumpets”) VII. Fouillis d'arcs-en-ciel, pour l'Ange qui annonce la fin du Temps (“Tangle of rainbows, for the Angel who announces the end of time) VIII. Louange à l'Immortalité de Jésus (“Praise to the immortality of Jesus”) This series made possible by a generous gift from Barbara Herman. PERFORMANCES MAGAZINE 20 ABOUT THE ARTISTS MICHELE ZUKOVSKY, clarinet, is an also produced recordings of several the Australian National University. American clarinetist and longest live performances by Zukovsky, The Montréal La Presse said that, serving member of the Los Angeles including the aforementioned Williams “Robert Davidovici is a born violinist Philharmonic Orchestra, serving Clarinet Concerto. Alongside her in the most complete sense of from 1961 at the age of 18 until her busy performing schedule, Zukovsky the word.” In October 2013, he retirement on December 20, 2015. -

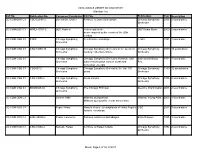

CSOA LEAGUE LIBRARY CD COLLECTION Member List Music

CSOA LEAGUE LIBRARY CD COLLECTION Member List Call No. Publication No. Composer/Conductor CD Title Publication Year Description CD COM BAR C3 CSO-CD-06-2 Barenboim, Daniel A tribute to Daniel Barenboim Chicago Symphony 2006 2 sound discs. Orchestra CD COM BBC C3 WMEF-0051-2 BBC Radio 4. This sceptred isle BBC Radio Music 2000 2 sound discs music inspired by the events of the 20th century. CD COM CSO C3 830IP Chicago Symphony Celebration Fantastique Teldec 1997 1 sound disc. Orchestra CD COM CSO C3 CSO CD00-10 Chicago Symphony Chicago Symphony Orchestra in the twentieth Chicago Symphony 2000 10 audio discs. Orchestra century: collector's choice Orchestra CD COM CSO C3 Chicago Symphony Chicago Symphony Orchestra trombone and Educational Brass 1971 1 sound disc. Orchestra tuba sections plays concert works and Rec. orchestral excerpts CD COM CSO C3 CSO90/12 Chicago Symphony Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the first 100 Chicago Symphony 1990 12 sound discs. Orchestra years Orchestra CD COM CSO C3 CSO CD95-2 Chicago Symphony Great soloists Chicago Symphony 1995 2 sound discs. Orchestra Orchestra CD COM CSO C3 B0000025-02 Chicago Symphony The Chicago Principal Deutche Grammopon 2003 2 sound discs. Orchestra CD COM DEN C3 Dennis, Allan Midwest young artists Midwest Young Artist 2003 1 sound disc Midwest young artitst : tenth anniversary CD COM FOG C3 Fogel, Henry Henry's choice : a compilation of Henry Fogel's CSO 2003 3 sound discs favorite recordings. CD COM FOS C3 2292-45860-2 Foster, Lawrence Famous romances and adagios Erato Disques 1985 1 sound disc. -

The Clarinet World

REVIEWS AUDIO NOTES by Kip Franklin Milton Babbit’s Composition for Four undauntedly masters the rapidly cascading Instruments begins with an extended arpeggios in the scherzando section and Stanley Drucker is unquestionably a titan clarinet passage that Drucker performs conveys control and color in the more of the clarinet world. In addition to his six in an improvisational off-the-cuff lyrical passages. This orchestration is decades with the New York Philharmonic manner. The work features a variety of a refreshing departure from the more (nearly five of them as principal clarinet), instrumental timbres and techniques, traditional clarinet and piano version. his career entails many commissions and resulting in a unique tapestry that Like Nature Moods and Contrasts, recordings. A new double-disc set, Stanley resembles the pointillistic writings of Weigl’s New England Suite showcases Drucker: Heritage Collection 6-7, Webern and Boulez. Valley Weigl’s Nature Drucker’s aptitude as a chamber musician. contains recordings of Drucker playing Moods ensues, with Drucker showcasing Her writing allows each instrument solo many of the most colossal works in the his ability to emulate the human voice. passages while still creating interwoven repertoire, as well as many important and Each of the five movements in this work and complex ensemble textures. Drucker’s rarely-played or obscure smaller works conveys a bucolic ambience with perfectly mellow, deep tone makes this an spanning the entirety of his career. That interwoven counterpoint between the especially memorable piece; at times it Drucker is on display as both a soloist clarinet, voice and violin. The balance in is contemplative and ponderous, and at and chamber musician throughout this this particular work is exceptional, with others jubilant and capricious. -

Prominent Schools of Clarinet Sound (National Styles)

Prominent Schools of Clarinet Sound (National Styles) German School (Oehler system, up to 27 keys) Description: dark, compact, well in tune but difficult to play very softly Players: Karl Leister, Sabine Meyer French School (Boehm system, 16 or 17 keys) Description: clear, bright/too bright, large dynamic range Players: Anthony Gigliotti, Phillippe Cuper Italian School (Boehm system) Description: voice-like quality Opera tradition Players: Ernesto Cavallini, Alessandro Carbonare American School (Boehm system) Description: Strong French influence but more open and wide, more air and flexibility Connections to jazz and film music Players: Larry Combs, Richard Stolzman, Charles Neidich, Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw JDG 20200815 The Most-used Types of Clarinets Band Eb Clarinet Bb Clarinet***** Eb Alto Clarinet Bb Bass Clarinet Eb Contra Alto Clarinet Bb Contra Bass Clarinet Orchestra Eb Clarinet C Clarinet Bb Clarinet A Clarinet Bb Bass Clarinet Worth Mentioning Basset Horn (in F) Basset Clarinet (in A) When an instrument plays its C and that sound/pitch is the same as the piano’s C, we say the instrument is “in C” When an instrument plays its C and that sound/pitch is the same as the piano’s Bb, we say the instrument is “in Bb” When an instrument plays its C and that sound/pitch is the same as the piano’s Eb, we say the instrument is “in Eb” And so on. JDG 20200815 Equipment Clarinets Rubber/plastic/ebonite, wood, carbon composites • Buffet • Selmer • LeBlanc • Yamaha • Bundy Mouthpieces Rubber, glass (metal) • Vandoren • Selmer • Yamaha • LeBlanc Reeds Cane or synthetic • Vandoren • Rico • Alexander • Gonzalez Ligatures and mouthpiece caps • Vandoren • Bonade (inverted) • LeBlanc • Rovner • Unnamed Tips • I purchase new instruments and used instruments. -

Courtesy of Eric Nelson, As Posted on Klarinet, 9 and 11 Feb 1997. Eric Nelson Is Clarinetist with the Lightwood Duo, an Actively Touring Clarinet/Guitar Duo

Courtesy of Eric Nelson, as posted on Klarinet, 9 and 11 Feb 1997. Eric Nelson is clarinetist with The Lightwood Duo, an actively touring clarinet/guitar duo. Their CDs are available through their website, http://www.lightwoodduo.com. About two weeks ago, there were some questions about Aage Oxenvad on the list. Having studied Nielsen and clarinet at the Royal Conservatory in Copenhagen [in 1979], I would like to pass on some first-hand information on Oxenvad. There are two major obstacles to acquiring accurate information about Danish music. First, much of the info exists only in the Danish language; not exactly a familiar language to most. Second, the Danes are not inclined to value the sharing of such information. To quote Tage Scharff, the clarinet professor with whom I studied: "You Americans [and English as well] love to get together and give lectures, deliver papers, and hold conferences. Here in Denmark, vi spiller! [we PLAY]". He was quite amused that I, a performing clarinetist, would be so interested in such material. On a posting on this list, Jarle Brosveet wrote: "In the first place Oxenvad did not inspire Nielsen to write the concerto, although he was the first to perform it. It was written at the request of Nielsen's benefactor and one-time student Carl Johan Michaelsen. Second, Oxenvad, who is described as a choleric, made this unflattering remark about Nielsen and the concerto: "He must be able to play the clarinet himself, otherwise the would hardly have been able to find the worst notes to play." Oxenvad performed it on several occasions with no apparent success although he reportedly did all he could, whatever that is supposed to mean. -

Timothy Bonenfant CV 2020-21

Timothy Bonenfant, D.M.A., Clarinetist Carr Education Fine-Arts Building, Room 217 ASU Station #10906; San Angelo, TX 76909-0906 (325) 486-6029 | [email protected] TEACHING EXPERIENCE 2005-present Professor of Music Angelo State University: San Angelo, TX Teach single reed studio (clarinet and saxophone) and advise students within the studio. Direct ASU Jazz Ensemble. Teach classes in Improvisation, Woodwind Methods, Jazz History, Introduction to Music and Survey of Rock and Roll. Direct/coach small woodwind ensembles (saxophone quartet, clarinet choir). 2017-2018 Adjunct Professor of Music Hardin Simmons University: Abilene, TX Taught saxophone studio while a search for a permanent replacement was conducted. 1996-2005 Instructor Las Vegas Academy for the Fine and Performing Arts: Las Vegas, NV Taught private lessons, fundamentals of music, and coached woodwind sectionals. 1993-2005 Lecturer University of Nevada, Las Vegas Taught Jazz Appreciation, Music Appreciation, History of Rock and Roll, History of American Popular Music, Finale: An Introduction, Music Fundamentals (for non-majors), Remedial Music Theory/Ear-Training. Also taught private lessons for clarinet and saxophone students. Developed new courses for the department; History of American Popular Music, and Finale: An Introduction. UNIVERSITY CLASSES TAUGHT Applied Music: Clarinet/Saxophone Woodwind Chamber Music Jazz Ensemble Improvisation Survey of Rock and Roll History of Jazz History of American Popular Music Introduction to Music Woodwind Methods Senior Recital Finale™ -

A Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in This Issue

Vol. 45 • No. 1 December 2017 Tao AChunxiao: Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in this issue... ClarinetFest® 2017 Report The Genesis of Gustav Jenner’s Clarinet Sonata D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jessica Harrie [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Dear ICA Members, Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Jessica Harrie, ope you are enjoying a wonderful new season Caroline Hartig, Rachel Yoder of music making with fulflling activities and MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR events. Many exciting things are happening in Gregory Barrett – [email protected] our organization. Te ICA believes that if you Hdo good things, good things happen! I want to thank everyone AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR who has contributed to our Capital Campaign. We especially Chris Nichols – [email protected] wish to thank Alan and Janette Stanek for their amazing gift of $11,250.00 to fund our competitions for the coming GRAPHIC DESIGN ClarinetFest® 2018. Te ICA is grateful for your generosity Karry Tomas Graphic Design and the generosity of all Capital Campaign donors. Please [email protected] visit www.youcaring.com/internationalclarinetassociation to Caroline Hartig make your donation today. We would love to hear your story ADVERTISING COORDINATOR and look forward to our continued campaign which will last Elizabeth Crawford – [email protected] through ClarinetFest® 2018. Also, visit www.clarinet.org/ donor-wall to check out our donor wall with many photos and thank-yous to those who INDEX MANAGER contributed to the ICA for ClarinetFest® 2017. -

School of Music 2016–2017

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut School of Music 2016–2017 School of Music 2016–2017 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 7 July 25, 2016 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 7 July 25, 2016 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 status as a protected veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Goff-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and protected veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valarie Stanley, Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 3rd Floor, 203.432.0849. -

CHARLES NEIDICH · Clarinetist/Conductor Biography

CHARLES NEIDICH · Clarinetist/Conductor Biography Charles Neidich (U.S.A.) Hailed by the New Yorker as "a master of his instrument and beyond a clarinetist” Charles Neidich has been described as one of the most mesmerizing musicians performing before the public today. He regularly appears as soloist and as collaborator in chamber music programs with leading ensembles including the Saint Louis Symphony, Minneapolis Symphony, I Musici di Montreal, Tafelmusik, Handel/Haydn Society, Royal Philharmonic, Deutsches Philharmonic, MDR Symphony, Yomiuri Symphony, National Symphony of Taiwan, and the Juilliard, Guarneri, Brentano, American, Mendelssohn, Carmina, Colorado, and Cavani String Quartets. He is currently a member of the New York Woodwind Quintet and a member emeritus of the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra. Charles Neidich has performed throughout Europe, Asia, and the United States, and is a sought after participant at many summer festivals such as the Marlboro and Sarasota festivals in the USA, the Orford and Domaines Forget festivals in Canada, BBC Proms in England, Festival Consonances and Pontivy in France, Corsi Internazionali di Perfezionamento in Italy, Kuhmo, Crusell Week, Turku, and Korsholm festivals in Finland, the Apeldoorn Festival in Holland, Music from Moritzburg in Germany, the Kirishima and Lilia summer festivals in Japan, and the Beijing Festival in China. When Charles Neidich began studying clarinet with his father, Irving Neidich at the age of 7, he had already started piano lessons with his mother, Litsa Gania Neidich. He continued studying both instruments, but the clarinet gradually won out, and he went at the age of 17 to continue studying with the noted clarinet teacher, Leon Russianoff.