Writing Murder: Elements of Gothic Horror in Matthew Milat's 'Meat Axe'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Korea Section 3

DEFENSE WHITE PAPER Message from the Minister of National Defense The year 2010 marked the 60th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War. Since the end of the war, the Republic of Korea has made such great strides and its economy now ranks among the 10-plus largest economies in the world. Out of the ashes of the war, it has risen from an aid recipient to a donor nation. Korea’s economic miracle rests on the strength and commitment of the ROK military. However, the threat of war and persistent security concerns remain undiminished on the Korean Peninsula. North Korea is threatening peace with its recent surprise attack against the ROK Ship CheonanDQGLWV¿ULQJRIDUWLOOHU\DW<HRQS\HRQJ Island. The series of illegitimate armed provocations by the North have left a fragile peace on the Korean Peninsula. Transnational and non-military threats coupled with potential conflicts among Northeast Asian countries add another element that further jeopardizes the Korean Peninsula’s security. To handle security threats, the ROK military has instituted its Defense Vision to foster an ‘Advanced Elite Military,’ which will realize the said Vision. As part of the efforts, the ROK military complemented the Defense Reform Basic Plan and has UHYDPSHGLWVZHDSRQSURFXUHPHQWDQGDFTXLVLWLRQV\VWHP,QDGGLWLRQLWKDVUHYDPSHGWKHHGXFDWLRQDOV\VWHPIRURI¿FHUVZKLOH strengthening the current training system by extending the basic training period and by taking other measures. The military has also endeavored to invigorate the defense industry as an exporter so the defense economy may develop as a new growth engine for the entire Korean economy. To reduce any possible inconveniences that Koreans may experience, the military has reformed its defense rules and regulations to ease the standards necessary to designate a Military Installation Protection Zone. -

The Report of the Daniel Morgan Independent Panel

The Report of the Daniel Morgan Independent Panel The Report of the Daniel Morgan Independent Panel June 2021 Volume 1 HC 11-I Return to an Address of the Honourable the House of Commons dated 15th June 2021 for The Report of the Daniel Morgan Independent Panel Volume 1 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 15th June 2021 HC 11-I © Crown copyright 2021 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. ISBN 978-1-5286-2479-4 Volume 1 of 3 CCS0220047602 06/21 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Daniel Morgan Independent Panel Daniel Morgan Independent Panel Home Office 2 Marsham Street London SW1P 4DF Rt Hon Priti Patel MP Home Secretary Home Office 2 Marsham Street London SW1P 4DF May 2021 Dear Home Secretary On behalf of the Daniel Morgan Independent Panel, I am pleased to present you with our Report for publication in Parliament. The establishment of the Daniel Morgan Independent Panel was announced by the Home Secretary, the Rt Hon Theresa May MP, on 10 May 2013 in a written statement to the House of Commons. -

In the Supreme Court of Florida Jason Andrew

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA JASON ANDREW SIMPSON, Appellant, v. Case No. SC07-0798 STATE OF FLORIDA, Appellee. ON APPEAL FROM THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE FOURTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT, IN AND FOR DUVAL COUNTY, FLORIDA ANSWER BRIEF OF APPELLEE BILL McCOLLUM ATTORNEY GENERAL STEPHEN R. WHITE ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL Florida Bar No. 159089 Office of the Attorney General PL-01, The Capitol Tallahassee, Fl 32399-1050 (850) 414-3300 Ext. 4579 (850) 487-0997 (FAX) COUNSEL FOR APPELLEE TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE# TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................... i TABLE OF CITATIONS ............................................... iii PRELIMINARY STATEMENT .............................................. 1 STATEMENT OF THE CASE AND FACTS ..................................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................................ 14 ARGUMENT ISSUE I: ISSUES I THROUGH IV: DID THE TRIAL COURT REVERSIBLY ERR IN ITS HANDLING OF JUROR CODY'S POST GUILTY-VERDICT STATEMENTS? .................................................... 15 A. Overview of Juror Cody-related claims ..................... 16 B. Contextual timeline ....................................... 16 C. Applicable preservation principles ........................ 18 D. Judge's Order ............................................. 19 E. Simpson's self-serving inference of Juror Cody's timidness ................................................. 21 ISSUE I: DID THE TRIAL COURT UNREASONABLY DENY A MOTION FOR NEW TRIAL WHERE, OVER A WEEK AFTER THE GUILTY VERDICT WAS RENDERED -

Murder and Women in 19Th-Century America Trial Accounts in the Yale Law Library

Murder and Women in 19th-Century America Trial Accounts in the Yale Law Library Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School Murder and Women in 19th-Century America Trial Accounts in the Yale Law Library An exhibition curated by Emma Molina Widener & Michael Widener November 19, 2014 – February 21, 2015 Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School New Haven, Connecticut Emma Molina Widener retired in December 2014 after Michael Widener is the Rare Book Librarian at the Lillian twenty years teaching college Spanish at the University of Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School, and is on the faculty Texas, Austin Community College, the University of New of the Rare Book School, University of Virginia. He was previ- Haven, Yale University, and most recently at Southern Con- ously Head of Special Collections at the Tarlton Law Library, necticut State University. Her bachelor’s degree is in politi- University of Texas at Austin. He has a bachelor’s degree in cal science and public administration from the Universidad journalism and a master’s in library & information science, Nacional Autónoma de México. From the University of Texas both from the University of Texas at Austin. at Austin she has a master’s in library science, a Certificate of Advanced Study in Latin American libraries & archives, a master’s in Latin American Studies, and A.B.D. in Spanish literature. She worked as a librarian at El Colegio de Mexico and at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México before going to the Office of the President of Mexico, where she was in charge of the Presidential Library. -

Round 5 Round 5 First Half

USABB National Bowl 2015-2016 Round 5 Round 5 First Half (1) Brigade 2506 tried to overthrow this leader but was stymied at Playa Giron. This man took control of his country after leading the 26th of July Movement to overthrow Fulgencio Batista; in that coup, he was assisted by Che Guevara. After nearly a (*) half-century of control, this leader passed power on to his 77-year-old brother, Raul in 2008. The Bay of Pigs invasion sought to overthrow, for ten points, what long-time dictator of Cuba? ANSWER: Fidel Castro (1) This man murdered his brother for leaping over the wall he had built around the Palatine Hill. For ten points each, Name this brother of Remus. ANSWER: Romulus Romulus and Remus were the legendary founder twins of this city. ANSWER: Rome According to legend, Romulus and Remus were abandoned in the Tiber, but washed ashore safely and were protected by this animal until shepherds found and raised them. ANSWER: she-wolf (2) This man made the film Chelsea Girls and filmed his lover sleeping for five hours in his film Sleep. This artist, who was shot by Valerie Solanas, used a fine mesh to transfer ink in order to create portraits of icons like (*) Mao Zedong and Marilyn Monroe. This artist produced silk screens in his studio, \The Factory," and he coined the term “fifteen minutes of fame." For ten points, name this Pop Artist who painted Cambell's soup cans. ANSWER: Andrew \Andy" Warhola, Jr Page 1 USABB National Bowl 2015-2016 Round 5 (2) Two singers who work in this type of location sing \Au fond du temple saint," and Peter Grimes commits suicide in this type of location. -

Narrative and Culture in Versions of the Lizzie Borden Story (A Performative Approach)

Intersecting Axes: Narrative and Culture in Versions of the Lizzie Borden Story (A Performative Approach) Stephanie Miller PhD Department of English and Related Literature September 2010 Miller 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines versions of the story of 32-year-old New Englander Lizzie Andrew Borden, famously accused of axe-murdering her stepmother Abby and father Andrew in 1892. Informed by narrative and feminist theories, Intersecting Axes draws upon interdisciplinary, contemporary re-workings of Judith Butler’s concept of “performativity” to explore the ways in which versions of the Lizzie Borden story negotiate such themes as repetition and difference, freedom and constraint, revision and reprisal, contingency and determinism, the specific and the universal. The project emphasizes and embraces the paradoxical sense in which interpretations are both enabled and constrained by the contextual situation of the interpreter and analyzes the relationship between individual versions and the cultural constructs they enact while purporting to describe. Moving away from symptomatic reading and its psychoanalytic underpinnings to focus upon the interpretive frames by which our understandings of Lizzie Borden versions (and of narrative/cultural texts more broadly) are shaped, this project exposes the complex performative processes whereby meaning is created. The chapters of this thesis offer contextual readings of a short story by Mary E. Wilkins Freeman, a ballet by Agnes de Mille, a made-for-television by Paul Wendkos, and a short story by Angela Carter to argue for the theoretical, political, narratological, cultural, and interpretive benefits of approaching the relationship between texts and contexts through a uniquely contemporary concept of performativity, bringing a valuable new perspective to current debates about the intersection of narrative and culture. -

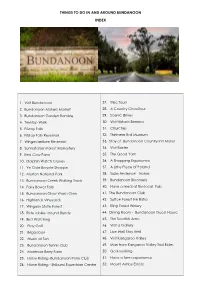

Things to Do in and Around Bundanoon Index

THINGS TO DO IN AND AROUND BUNDANOON INDEX 1. Visit Bundanoon 27. Trike Tours 2. Bundanoon Makers Market 28. A Country Chauffeur 3. Bundanoon Garden Ramble 29. Scenic Drives 4. Treetop Walk 30. Visit Historic Berrima 5. Fitzroy Falls 31. Churches 6. Fitzroy Falls Reservoir 32. Thirlmere Rail Museum 7. Wingecarribee Reservoir 33. Stay at Bundanoon Country Inn Motel 8. Sunnataram Forest Monastery 34. Visit Exeter 9. Red Cow Farm 35. The Good Yarn 10. Dolphin Watch Cruises 36. A Shopping Experience 11. Ye Olde Bicycle Shoppe 37. A Little Piece of Poland 12. Morton National Park 38. Suzie Anderson - Home 13. Bundanoon Creek Walking Track 39. Bundanoon Bloomery 14. Fairy Bower Falls 40. Have a meal at the local Pub 15. Bundanoon Glow Worm Glen 41. The Bundanoon Club 16. Highlands Vineyards 42. Sutton Forest Inn Bistro 17. Wingello State Forest 43. Eling Forest Winery 18. Ride a bike around Bundy 44. Dining Room - Bundanoon Guest House 19. Bird Watching 45. The Scottish Arms 20. Play Golf 46. Visit a Gallery 21. Brigadoon 47. Live Well Stay Well 22. Music at Ten 48. Visit Kangaroo Valley 23. Bundanoon Tennis Club 49. Man from Kangaroo Valley Trial Rides 24. Montrose Berry Farm 50. Go Kayaking 25. Horse Riding -Bundanoon Pony Club 51. Have a farm experience 26. Horse Riding - Shibumi Equestrian Centre 52. Mount Ashby Estate 1. VISIT BUNDANOON https://www.southern-highlands.com.au/visitors/visitors-towns-and-villages/bundanoon Bundanoon is an Aboriginal name meaning "place of deep gullies" and was formerly known as Jordan's Crossing. Bundanoon is colloquially known as Bundy / Bundi. -

South Korea: Defense White Paper 2010

DEFENSE WHITE PAPER Message from the Minister of National Defense The year 2010 marked the 60th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War. Since the end of the war, the Republic of Korea has made such great strides and its economy now ranks among the 10-plus largest economies in the world. Out of the ashes of the war, it has risen from an aid recipient to a donor nation. Korea’s economic miracle rests on the strength and commitment of the ROK military. However, the threat of war and persistent security concerns remain undiminished on the Korean Peninsula. North Korea is threatening peace with its recent surprise attack against the ROK Ship CheonanDQGLWV¿ULQJRIDUWLOOHU\DW<HRQS\HRQJ Island. The series of illegitimate armed provocations by the North have left a fragile peace on the Korean Peninsula. Transnational and non-military threats coupled with potential conflicts among Northeast Asian countries add another element that further jeopardizes the Korean Peninsula’s security. To handle security threats, the ROK military has instituted its Defense Vision to foster an ‘Advanced Elite Military,’ which will realize the said Vision. As part of the efforts, the ROK military complemented the Defense Reform Basic Plan and has UHYDPSHGLWVZHDSRQSURFXUHPHQWDQGDFTXLVLWLRQV\VWHP,QDGGLWLRQLWKDVUHYDPSHGWKHHGXFDWLRQDOV\VWHPIRURI¿FHUVZKLOH strengthening the current training system by extending the basic training period and by taking other measures. The military has also endeavored to invigorate the defense industry as an exporter so the defense economy may develop as a new growth engine for the entire Korean economy. To reduce any possible inconveniences that Koreans may experience, the military has reformed its defense rules and regulations to ease the standards necessary to designate a Military Installation Protection Zone. -

Adjudicating Homicide: the Legal Framework and Social Norms

1 Adjudicating Homicide: The Legal Framework and Social Norms Robert Asher, Lawrence B. Goodheart, and Alan Rogers Mark Twain once asked, “If the desire to kill and the opportunity to kill came always together, who would escape hanging?” The great humorist was entertaining. But he was too glib. The essays in this volume indicate that throughout the history of England’s North American colonies and the United States, legal decisions about the guilt of people accused of murder and the proper punishment of those convicted of murder have not followed automati- cally any set of principles and procedures. People, with all their human preju- dices, create murder jurisprudence—the social rules that govern the arrest, trial, and punishment of humans accused of homicide, i.e., the killing of a human being. Between colonial and present times, the dominant English-speaking in- habitants in the area that became the United States have altered significantly the rules of criminal homicide, providing increasing numbers of constitu- tional and judicially constructed safeguards to those accused of homicide and to convicted murderers. Changing community ideas about insanity, the devel- opment of children, gender roles, and racism have affected the law. The essays in Murder on Trial analyze the effects of changing social norms on the development and application of the legal frameworks used to determine the motives and the ability to distinguish between right and wrong of people who are accused of a homicide. Especially after 1930, fewer white Americans—but not all—accepted the notion that racial and ethnic minorities were biologically and morally inferior. -

DOWNLOAD the Educators' Guide

Educators’ Guide Includes Common Core State Standards Correlations RHTeachersLibrarians.com ABOUT THE AUTHOR Sarah Miller is the author of two historical fiction novels, Miss Spitfire: Reaching Helen Keller, which was called “an accomplished debut” in a starred review from Booklist and was named an ALA-ALSC Notable Children’s Book; and The Lost Crown, about the Romanovs, hailed as “fascinating” in a starred review from Kirkus Reviews and named an ALA-YALSA Best Book for Young Adults. Pre-Reading Activity Discuss the definition of the word rumor. Ask students to offer examples of a time when they were or a friend was a victim of a false story. Next, discuss how stories that are told second- and thirdhand have a way of changing as they are repeated. As students prepare to read The Borden Murders, play a game of telephone to underscore how information passed from one person to the next can very easily change as it moves down the line. After playing the game a few times, lead a class discussion about how passing rumors can be damaging and hurtful. Grades 5 & up HC: 978-0-553-49808-0 GLB: 978-0-553-49809-7 Lizzie Borden Took an Axe (pp. xiii–x) EL: 978-0-553-49810-3 For Discussion: The author writes that the “brutal About the Book hatchet murders of Miss Lizbeth’s father and More than 120 years after Andrew and Abby stepmother captured the nation’s attention.” What Borden were brutally murdered in their Fall does it mean to capture the attention of an entire River, Massachusetts, home, the name Lizzie nation, and what types of events are powerful Borden can still send chills up the spine. -

Wingecarribee Local Government Area Final Report 2015 09

Rating and Taxing Valuation Procedures Manual v6.6.2 Wingecarribee Local Government Area Final Report 2015 09 November 2015 Rating and Taxing Valuation Procedures Manual v6.6.2 Page 1 Rating and Taxing Valuation Procedures Manual v6.6.2 Executive Summary LGA Overview Wingecarribee Local Government Area Wingecarribee Shire is located 75 kilometres from the south western fringe of Sydney and 110 kilometres from Sydney central business district. The Shire lies within the Sydney – Canberra – Melbourne transport corridor on the Southern rail line and Hume Highway. The M5 motorway provides rapid access to Campbelltown, Liverpool and other key metropolitan centres within Sydney. Wingecarribee is also referred to as the Southern Highlands due to its position on a spur of the Great Dividing Range some 640 to 800 metres above sea level. Wingecarribee Shire is predominantly rural in character with agricultural lands separating towns and villages characterised by unique landscape and aesthetic appeal. Development pressures are significant and include subdivision for residential and lifestyle purposes, infrastructure, industry and agriculture. The Southern Highlands forms part of Gundungurra tribal lands and preservation of Aboriginal heritage is significant. European settlement dates back to the early 1800s with first contact between Aboriginal people and Europeans occurring in 1798. Settlement followed in 1821 at Bong Bong. The Shire is rich in biodiversity with large areas of high conservation value including part of the World Heritage Greater Blue Mountains area and two declared wilderness areas. Environmental features include cold climatic conditions, rugged topography and significant areas of state forest, national park and other protected lands that form part of the Sydney water catchment area. -

Reliving the Horrors of the Ivan Milat Case

Reliving the horrors of the Ivan Milat case John Thompson | ABC, The Drum | Updated 31st August, 2010 "Police are investigating the discovery of human remains found in the Belanglo State Forest". Seven times I said those words as a former police reporter. Twice I broke the news to the world that another body had been discovered. But that was the second half of 1993. This week's news of one more discovery has brought the horror of the backpacker serial killings back to the present. I remember driving into the Belanglo State Forest for the first time. I nearly missed the turn- off. There's only a small sign on the right side of the Hume Highway, heading south from Sydney just past Mittagong. It's a rough dirt track that goes past a homestead. I remember trying to imagine what it must have been like to have been one of the backpackers: Deborah Everist, James Gibson, Simone Schmidl, Anja Habschied, Gabor Neugebauer, Joanne Walters and Caroline Clarke. The sheer terror each of them must have felt when this seemingly pleasant man with small eyes and a beard, who had offered them a lift, suddenly turned off the highway, pulled out a gun and drove into bush far far away from civilisation and any possible help. Knowing that this track, this bush, were some of the last images each of the young backpackers saw gave me more than a slight chill - to this day it still makes me feel sick. What gives someone the compulsion to kill like this? And to do it over and over again? How do they live with themselves? The man who knows most about Ivan Milat and what he did to each of his seven victims is cautioning the public not to draw too many links with the weekend discovery by trail bike riders.