Narrative and Culture in Versions of the Lizzie Borden Story (A Performative Approach)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Korea Section 3

DEFENSE WHITE PAPER Message from the Minister of National Defense The year 2010 marked the 60th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War. Since the end of the war, the Republic of Korea has made such great strides and its economy now ranks among the 10-plus largest economies in the world. Out of the ashes of the war, it has risen from an aid recipient to a donor nation. Korea’s economic miracle rests on the strength and commitment of the ROK military. However, the threat of war and persistent security concerns remain undiminished on the Korean Peninsula. North Korea is threatening peace with its recent surprise attack against the ROK Ship CheonanDQGLWV¿ULQJRIDUWLOOHU\DW<HRQS\HRQJ Island. The series of illegitimate armed provocations by the North have left a fragile peace on the Korean Peninsula. Transnational and non-military threats coupled with potential conflicts among Northeast Asian countries add another element that further jeopardizes the Korean Peninsula’s security. To handle security threats, the ROK military has instituted its Defense Vision to foster an ‘Advanced Elite Military,’ which will realize the said Vision. As part of the efforts, the ROK military complemented the Defense Reform Basic Plan and has UHYDPSHGLWVZHDSRQSURFXUHPHQWDQGDFTXLVLWLRQV\VWHP,QDGGLWLRQLWKDVUHYDPSHGWKHHGXFDWLRQDOV\VWHPIRURI¿FHUVZKLOH strengthening the current training system by extending the basic training period and by taking other measures. The military has also endeavored to invigorate the defense industry as an exporter so the defense economy may develop as a new growth engine for the entire Korean economy. To reduce any possible inconveniences that Koreans may experience, the military has reformed its defense rules and regulations to ease the standards necessary to designate a Military Installation Protection Zone. -

The Report of the Daniel Morgan Independent Panel

The Report of the Daniel Morgan Independent Panel The Report of the Daniel Morgan Independent Panel June 2021 Volume 1 HC 11-I Return to an Address of the Honourable the House of Commons dated 15th June 2021 for The Report of the Daniel Morgan Independent Panel Volume 1 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 15th June 2021 HC 11-I © Crown copyright 2021 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. ISBN 978-1-5286-2479-4 Volume 1 of 3 CCS0220047602 06/21 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Daniel Morgan Independent Panel Daniel Morgan Independent Panel Home Office 2 Marsham Street London SW1P 4DF Rt Hon Priti Patel MP Home Secretary Home Office 2 Marsham Street London SW1P 4DF May 2021 Dear Home Secretary On behalf of the Daniel Morgan Independent Panel, I am pleased to present you with our Report for publication in Parliament. The establishment of the Daniel Morgan Independent Panel was announced by the Home Secretary, the Rt Hon Theresa May MP, on 10 May 2013 in a written statement to the House of Commons. -

In the Supreme Court of Florida Jason Andrew

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA JASON ANDREW SIMPSON, Appellant, v. Case No. SC07-0798 STATE OF FLORIDA, Appellee. ON APPEAL FROM THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE FOURTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT, IN AND FOR DUVAL COUNTY, FLORIDA ANSWER BRIEF OF APPELLEE BILL McCOLLUM ATTORNEY GENERAL STEPHEN R. WHITE ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL Florida Bar No. 159089 Office of the Attorney General PL-01, The Capitol Tallahassee, Fl 32399-1050 (850) 414-3300 Ext. 4579 (850) 487-0997 (FAX) COUNSEL FOR APPELLEE TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE# TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................... i TABLE OF CITATIONS ............................................... iii PRELIMINARY STATEMENT .............................................. 1 STATEMENT OF THE CASE AND FACTS ..................................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................................ 14 ARGUMENT ISSUE I: ISSUES I THROUGH IV: DID THE TRIAL COURT REVERSIBLY ERR IN ITS HANDLING OF JUROR CODY'S POST GUILTY-VERDICT STATEMENTS? .................................................... 15 A. Overview of Juror Cody-related claims ..................... 16 B. Contextual timeline ....................................... 16 C. Applicable preservation principles ........................ 18 D. Judge's Order ............................................. 19 E. Simpson's self-serving inference of Juror Cody's timidness ................................................. 21 ISSUE I: DID THE TRIAL COURT UNREASONABLY DENY A MOTION FOR NEW TRIAL WHERE, OVER A WEEK AFTER THE GUILTY VERDICT WAS RENDERED -

Murder and Women in 19Th-Century America Trial Accounts in the Yale Law Library

Murder and Women in 19th-Century America Trial Accounts in the Yale Law Library Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School Murder and Women in 19th-Century America Trial Accounts in the Yale Law Library An exhibition curated by Emma Molina Widener & Michael Widener November 19, 2014 – February 21, 2015 Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School New Haven, Connecticut Emma Molina Widener retired in December 2014 after Michael Widener is the Rare Book Librarian at the Lillian twenty years teaching college Spanish at the University of Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School, and is on the faculty Texas, Austin Community College, the University of New of the Rare Book School, University of Virginia. He was previ- Haven, Yale University, and most recently at Southern Con- ously Head of Special Collections at the Tarlton Law Library, necticut State University. Her bachelor’s degree is in politi- University of Texas at Austin. He has a bachelor’s degree in cal science and public administration from the Universidad journalism and a master’s in library & information science, Nacional Autónoma de México. From the University of Texas both from the University of Texas at Austin. at Austin she has a master’s in library science, a Certificate of Advanced Study in Latin American libraries & archives, a master’s in Latin American Studies, and A.B.D. in Spanish literature. She worked as a librarian at El Colegio de Mexico and at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México before going to the Office of the President of Mexico, where she was in charge of the Presidential Library. -

Round 5 Round 5 First Half

USABB National Bowl 2015-2016 Round 5 Round 5 First Half (1) Brigade 2506 tried to overthrow this leader but was stymied at Playa Giron. This man took control of his country after leading the 26th of July Movement to overthrow Fulgencio Batista; in that coup, he was assisted by Che Guevara. After nearly a (*) half-century of control, this leader passed power on to his 77-year-old brother, Raul in 2008. The Bay of Pigs invasion sought to overthrow, for ten points, what long-time dictator of Cuba? ANSWER: Fidel Castro (1) This man murdered his brother for leaping over the wall he had built around the Palatine Hill. For ten points each, Name this brother of Remus. ANSWER: Romulus Romulus and Remus were the legendary founder twins of this city. ANSWER: Rome According to legend, Romulus and Remus were abandoned in the Tiber, but washed ashore safely and were protected by this animal until shepherds found and raised them. ANSWER: she-wolf (2) This man made the film Chelsea Girls and filmed his lover sleeping for five hours in his film Sleep. This artist, who was shot by Valerie Solanas, used a fine mesh to transfer ink in order to create portraits of icons like (*) Mao Zedong and Marilyn Monroe. This artist produced silk screens in his studio, \The Factory," and he coined the term “fifteen minutes of fame." For ten points, name this Pop Artist who painted Cambell's soup cans. ANSWER: Andrew \Andy" Warhola, Jr Page 1 USABB National Bowl 2015-2016 Round 5 (2) Two singers who work in this type of location sing \Au fond du temple saint," and Peter Grimes commits suicide in this type of location. -

Issues of Gender in Muscle Beach Party (1964) Joan Ormrod, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by E-space: Manchester Metropolitan University's Research Repository Issues of Gender in Muscle Beach Party (1964) Joan Ormrod, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK Muscle Beach Party (1964) is the second in a series of seven films made by American International Pictures (AIP) based around a similar set of characters and set (by and large) on the beach. The Beach Party series, as it came to be known, rode on a wave of surfing fever amongst teenagers in the early 1960s. The films depicted the carefree and affluent lifestyle of a group of middle class, white Californian teenagers on vacation and are described by Granat as, "…California's beautiful people in a setting that attracted moviegoers. The films did not 'hold a mirror up to nature', yet they mirrored the glorification of California taking place in American culture." (Granat, 1999:191) The films were critically condemned. The New York Times critic, for instance, noted, "…almost the entire cast emerges as the dullest bunch of meatballs ever, with the old folks even sillier than the kids..." (McGee, 1984: 150) Despite their dismissal as mere froth, the Beach Party series may enable an identification of issues of concern in the wider American society of the early sixties. The Beach Party films are sequential, beginning with Beach Party (1963) advertised as a "musical comedy of summer, surfing and romance" (Beach Party Press Pack). Beach Party was so successful that AIP wasted no time in producing six further films; Muscle Beach Party (1964), Pajama Party (1964) Bikini Beach (1964), Beach Blanket Bingo (1965) How to Stuff a Wild Bikini (1965) and The Ghost in the Invisible Bikini (1966). -

South Korea: Defense White Paper 2010

DEFENSE WHITE PAPER Message from the Minister of National Defense The year 2010 marked the 60th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War. Since the end of the war, the Republic of Korea has made such great strides and its economy now ranks among the 10-plus largest economies in the world. Out of the ashes of the war, it has risen from an aid recipient to a donor nation. Korea’s economic miracle rests on the strength and commitment of the ROK military. However, the threat of war and persistent security concerns remain undiminished on the Korean Peninsula. North Korea is threatening peace with its recent surprise attack against the ROK Ship CheonanDQGLWV¿ULQJRIDUWLOOHU\DW<HRQS\HRQJ Island. The series of illegitimate armed provocations by the North have left a fragile peace on the Korean Peninsula. Transnational and non-military threats coupled with potential conflicts among Northeast Asian countries add another element that further jeopardizes the Korean Peninsula’s security. To handle security threats, the ROK military has instituted its Defense Vision to foster an ‘Advanced Elite Military,’ which will realize the said Vision. As part of the efforts, the ROK military complemented the Defense Reform Basic Plan and has UHYDPSHGLWVZHDSRQSURFXUHPHQWDQGDFTXLVLWLRQV\VWHP,QDGGLWLRQLWKDVUHYDPSHGWKHHGXFDWLRQDOV\VWHPIRURI¿FHUVZKLOH strengthening the current training system by extending the basic training period and by taking other measures. The military has also endeavored to invigorate the defense industry as an exporter so the defense economy may develop as a new growth engine for the entire Korean economy. To reduce any possible inconveniences that Koreans may experience, the military has reformed its defense rules and regulations to ease the standards necessary to designate a Military Installation Protection Zone. -

The Field Guide to Sponsored Films

THE FIELD GUIDE TO SPONSORED FILMS by Rick Prelinger National Film Preservation Foundation San Francisco, California Rick Prelinger is the founder of the Prelinger Archives, a collection of 51,000 advertising, educational, industrial, and amateur films that was acquired by the Library of Congress in 2002. He has partnered with the Internet Archive (www.archive.org) to make 2,000 films from his collection available online and worked with the Voyager Company to produce 14 laser discs and CD-ROMs of films drawn from his collection, including Ephemeral Films, the series Our Secret Century, and Call It Home: The House That Private Enterprise Built. In 2004, Rick and Megan Shaw Prelinger established the Prelinger Library in San Francisco. National Film Preservation Foundation 870 Market Street, Suite 1113 San Francisco, CA 94102 © 2006 by the National Film Preservation Foundation Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Prelinger, Rick, 1953– The field guide to sponsored films / Rick Prelinger. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-9747099-3-X (alk. paper) 1. Industrial films—Catalogs. 2. Business—Film catalogs. 3. Motion pictures in adver- tising. 4. Business in motion pictures. I. Title. HF1007.P863 2006 011´.372—dc22 2006029038 CIP This publication was made possible through a grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. It may be downloaded as a PDF file from the National Film Preservation Foundation Web site: www.filmpreservation.org. Photo credits Cover and title page (from left): Admiral Cigarette (1897), courtesy of Library of Congress; Now You’re Talking (1927), courtesy of Library of Congress; Highlights and Shadows (1938), courtesy of George Eastman House. -

Adjudicating Homicide: the Legal Framework and Social Norms

1 Adjudicating Homicide: The Legal Framework and Social Norms Robert Asher, Lawrence B. Goodheart, and Alan Rogers Mark Twain once asked, “If the desire to kill and the opportunity to kill came always together, who would escape hanging?” The great humorist was entertaining. But he was too glib. The essays in this volume indicate that throughout the history of England’s North American colonies and the United States, legal decisions about the guilt of people accused of murder and the proper punishment of those convicted of murder have not followed automati- cally any set of principles and procedures. People, with all their human preju- dices, create murder jurisprudence—the social rules that govern the arrest, trial, and punishment of humans accused of homicide, i.e., the killing of a human being. Between colonial and present times, the dominant English-speaking in- habitants in the area that became the United States have altered significantly the rules of criminal homicide, providing increasing numbers of constitu- tional and judicially constructed safeguards to those accused of homicide and to convicted murderers. Changing community ideas about insanity, the devel- opment of children, gender roles, and racism have affected the law. The essays in Murder on Trial analyze the effects of changing social norms on the development and application of the legal frameworks used to determine the motives and the ability to distinguish between right and wrong of people who are accused of a homicide. Especially after 1930, fewer white Americans—but not all—accepted the notion that racial and ethnic minorities were biologically and morally inferior. -

Newbev201902 FRONT

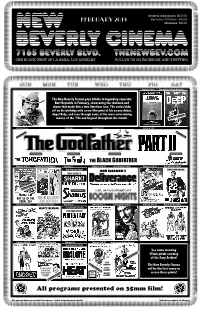

General Admission: $10.00 February 2019 Seniors / Children: $6.00 NEW Matinees: $6.00 BEVERLY cinema 7165 BEVERLY BLVD. THENEWBEV.COM ONE BLOCK WEST OF LA BREA, LOS ANGELES FOLLOW US ON FACEBOOK AND TWITTER! February 1 & 2 Two written by Peter Benchley The New Beverly Cinema pays tribute to legendary superstar Burt Reynolds in February, showcasing the charisma and charm that made him a true American icon. The series kicks off on his birthday with a rare film print of his screen debut, Angel Baby, and runs through some of his most entertaining movies of the ‘70s and beyond throughout the month. 4-track Mag Print DIRECTED BY STEVEN SPIELBERG February 3 & 4 February 5 February 6 & 7 February 8 & 9 IB Tech Print IB Tech Print MIDNIGHT SHOW! MIDNIGHT SHOW! MIDNIGHT SHOW! MIDNIGHT SHOW! THE BLACK GODFATHER (SATURDAY ONLY) February 10 & 11 Directed by Paul Wendkos February 12 February 13 & 14Burt Reynolds Tribute February 15 & 16 Burt Reynolds Tribute Burt Reynolds Tribute JOHN BOORMAN’S BURT REYNOLDS Sam Fuller’s SHARK! Sony Archive Print SONY ARCHIVE PRINT PAUL THOMAS ANDERSON’S BATTLE OF THE GEORGE HAMILTON CORAL SEA BURT REYNOLDS February 17 & 18 French Foreign Legion February 19 February 20 & 21 Burt Reynolds Tribute February 22 & 23 Burt Reynolds Tribute MARTY FELDMAN Jamaa Fanaka Double LEON ISAAC KENNEDY February 24 & 25 Directed by Paul Wendkos February 26 February 27 & 28 Jack Lemmon Double Feature Burt Reynolds Tribute See some stunning 35mm prints courtesy of the Sony Archive! Sony Archive Print JACK Sony Archive Print LEMMON The -

American Auteur Cinema: the Last – Or First – Great Picture Show 37 Thomas Elsaesser

For many lovers of film, American cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s – dubbed the New Hollywood – has remained a Golden Age. AND KING HORWATH PICTURE SHOW ELSAESSER, AMERICAN GREAT THE LAST As the old studio system gave way to a new gen- FILMFILM FFILMILM eration of American auteurs, directors such as Monte Hellman, Peter Bogdanovich, Bob Rafel- CULTURE CULTURE son, Martin Scorsese, but also Robert Altman, IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION James Toback, Terrence Malick and Barbara Loden helped create an independent cinema that gave America a different voice in the world and a dif- ferent vision to itself. The protests against the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and feminism saw the emergence of an entirely dif- ferent political culture, reflected in movies that may not always have been successful with the mass public, but were soon recognized as audacious, creative and off-beat by the critics. Many of the films TheThe have subsequently become classics. The Last Great Picture Show brings together essays by scholars and writers who chart the changing evaluations of this American cinema of the 1970s, some- LaLastst Great Great times referred to as the decade of the lost generation, but now more and more also recognised as the first of several ‘New Hollywoods’, without which the cin- American ema of Francis Coppola, Steven Spiel- American berg, Robert Zemeckis, Tim Burton or Quentin Tarantino could not have come into being. PPictureicture NEWNEW HOLLYWOODHOLLYWOOD ISBN 90-5356-631-7 CINEMACINEMA ININ ShowShow EDITEDEDITED BY BY THETHE -

Gidget Documentary a Hit at Maritime Museum

Gidget documentary a hit at maritime museum NIKKI GREY, NEWS-PRESS CORRESPONDENT September 25, 2011 6:46 AM With surf legends in attendance for the film screening of "Accidental Icon," the Santa Barbara Maritime Museum, Munger Theater sold out and had to open a second area for overflow seating. The documentary tells the story of Kathy Zuckerman, the woman who inspired "Gidget" -- the character who broke boundaries to discover surfing in the 1950s and gave rise to the novel, television series and movies. Kathy Kohner Zuckerman, the real The story of 15-year-old Gidget -- a moniker "Gidget," poses on a surfboard before the combining the words "girl" and "midget" -- centers screening of her film Saturday at the around a feisty girl who learned how to surf in Malibu Santa Barbara Maritime Museum long before women surfers were common and prior to the popularity of the sport. MIKE ELIASON/NEWS-PRESS Gidget became a role model to girls worldwide while simultaneously changing the surfing way of life after Mrs. Zuckerman's father wrote a book based on her unusual exploits. Greg Gora, executive director of the Maritime Museum, expressed his excitement about the documentary screening's success to the News-Press. "I've been here for 41/2 years and I've never had the theater sell out like this before," he said. "(Gidget) is an icon for female surfers." Mrs. Zuckerman bounced in and out of the theater, chatting excitedly about the energy of the crowd. "It's so exciting here," Mrs. Zuckerman said. "It's such a great audience.