Belanglo State Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Things to Do in and Around Bundanoon Index

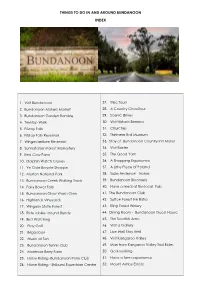

THINGS TO DO IN AND AROUND BUNDANOON INDEX 1. Visit Bundanoon 27. Trike Tours 2. Bundanoon Makers Market 28. A Country Chauffeur 3. Bundanoon Garden Ramble 29. Scenic Drives 4. Treetop Walk 30. Visit Historic Berrima 5. Fitzroy Falls 31. Churches 6. Fitzroy Falls Reservoir 32. Thirlmere Rail Museum 7. Wingecarribee Reservoir 33. Stay at Bundanoon Country Inn Motel 8. Sunnataram Forest Monastery 34. Visit Exeter 9. Red Cow Farm 35. The Good Yarn 10. Dolphin Watch Cruises 36. A Shopping Experience 11. Ye Olde Bicycle Shoppe 37. A Little Piece of Poland 12. Morton National Park 38. Suzie Anderson - Home 13. Bundanoon Creek Walking Track 39. Bundanoon Bloomery 14. Fairy Bower Falls 40. Have a meal at the local Pub 15. Bundanoon Glow Worm Glen 41. The Bundanoon Club 16. Highlands Vineyards 42. Sutton Forest Inn Bistro 17. Wingello State Forest 43. Eling Forest Winery 18. Ride a bike around Bundy 44. Dining Room - Bundanoon Guest House 19. Bird Watching 45. The Scottish Arms 20. Play Golf 46. Visit a Gallery 21. Brigadoon 47. Live Well Stay Well 22. Music at Ten 48. Visit Kangaroo Valley 23. Bundanoon Tennis Club 49. Man from Kangaroo Valley Trial Rides 24. Montrose Berry Farm 50. Go Kayaking 25. Horse Riding -Bundanoon Pony Club 51. Have a farm experience 26. Horse Riding - Shibumi Equestrian Centre 52. Mount Ashby Estate 1. VISIT BUNDANOON https://www.southern-highlands.com.au/visitors/visitors-towns-and-villages/bundanoon Bundanoon is an Aboriginal name meaning "place of deep gullies" and was formerly known as Jordan's Crossing. Bundanoon is colloquially known as Bundy / Bundi. -

Emily O'grady Thesis

Subverting the Serial Gaze: Interrogating the Legacies of Intergenerational Violence in Serial Killer Narratives Emily O’Grady Bachelor of Fine Arts (Honours) Creative Industries: Creative Writing and Literary Studies Queensland University of Technology Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 1 Abstract This thesis subverts, disrupts and reimagines dominant narratives of fictional serial crime through a hybrid research paradigm of creative practice and critical analysis. The creative output of this thesis is an 80,000 word literary novel titled The Yellow House, accompanied by a 20,000 word critical exegesis. In the following, I argue that current fictional iterations of the serial killer literary genre are rigidly conservative, and remain fixed within the safe confines of genre conventions wherein the narrative bears little resemblance to how abject violence and the aftermath of serial crime plays out in real life. The broad framework of genre theory, accompanied by trauma theory, allows for an examination of the serial killer genre to identify the space in which my creative practice—an Australian, literary rendering of serial crime—fits as an extension and subversion of the genre. By reimagining the Australian serial killer narrative, I seek to challenge the reductive serial killer genre, and come to a potential offering of serial homicide that interrogates how the legacies of abject violence can be transmitted across generations. I do this by shifting the focus onto the aftermath of the crime and its numerous victims—in particular, the descendants of serial killers. The Yellow House presents a destabilising fictionalisation of serial crime that disrupts the conventions of the genre in order to contend with the complexity and instability of serial homicide. -

Wingecarribee Local Government Area Final Report 2015 09

Rating and Taxing Valuation Procedures Manual v6.6.2 Wingecarribee Local Government Area Final Report 2015 09 November 2015 Rating and Taxing Valuation Procedures Manual v6.6.2 Page 1 Rating and Taxing Valuation Procedures Manual v6.6.2 Executive Summary LGA Overview Wingecarribee Local Government Area Wingecarribee Shire is located 75 kilometres from the south western fringe of Sydney and 110 kilometres from Sydney central business district. The Shire lies within the Sydney – Canberra – Melbourne transport corridor on the Southern rail line and Hume Highway. The M5 motorway provides rapid access to Campbelltown, Liverpool and other key metropolitan centres within Sydney. Wingecarribee is also referred to as the Southern Highlands due to its position on a spur of the Great Dividing Range some 640 to 800 metres above sea level. Wingecarribee Shire is predominantly rural in character with agricultural lands separating towns and villages characterised by unique landscape and aesthetic appeal. Development pressures are significant and include subdivision for residential and lifestyle purposes, infrastructure, industry and agriculture. The Southern Highlands forms part of Gundungurra tribal lands and preservation of Aboriginal heritage is significant. European settlement dates back to the early 1800s with first contact between Aboriginal people and Europeans occurring in 1798. Settlement followed in 1821 at Bong Bong. The Shire is rich in biodiversity with large areas of high conservation value including part of the World Heritage Greater Blue Mountains area and two declared wilderness areas. Environmental features include cold climatic conditions, rugged topography and significant areas of state forest, national park and other protected lands that form part of the Sydney water catchment area. -

Reliving the Horrors of the Ivan Milat Case

Reliving the horrors of the Ivan Milat case John Thompson | ABC, The Drum | Updated 31st August, 2010 "Police are investigating the discovery of human remains found in the Belanglo State Forest". Seven times I said those words as a former police reporter. Twice I broke the news to the world that another body had been discovered. But that was the second half of 1993. This week's news of one more discovery has brought the horror of the backpacker serial killings back to the present. I remember driving into the Belanglo State Forest for the first time. I nearly missed the turn- off. There's only a small sign on the right side of the Hume Highway, heading south from Sydney just past Mittagong. It's a rough dirt track that goes past a homestead. I remember trying to imagine what it must have been like to have been one of the backpackers: Deborah Everist, James Gibson, Simone Schmidl, Anja Habschied, Gabor Neugebauer, Joanne Walters and Caroline Clarke. The sheer terror each of them must have felt when this seemingly pleasant man with small eyes and a beard, who had offered them a lift, suddenly turned off the highway, pulled out a gun and drove into bush far far away from civilisation and any possible help. Knowing that this track, this bush, were some of the last images each of the young backpackers saw gave me more than a slight chill - to this day it still makes me feel sick. What gives someone the compulsion to kill like this? And to do it over and over again? How do they live with themselves? The man who knows most about Ivan Milat and what he did to each of his seven victims is cautioning the public not to draw too many links with the weekend discovery by trail bike riders. -

Mullum School Touchdown Harsh Feedback Over Fl Ood Response

THE BYRON SHIRE Volume 33 #14 Wednesday, September 12, 2018 S www.echo.net.au Phone 02 6684 1777 [email protected] [email protected] 23,200 copies every week DEMANDING THE BEST AND REGRETTABLY ACCEPTING LESS SINCE 1986 Mullum school touchdown Harsh feedback over fl ood response Paul Bibby We’ve subsequently had a test run during a possible fl ood event that Th e Byron Shire community has little didn’t eventuate and we found that faith in the ability of local authori- our warning systems and communi- ties such as Council and the police to cation had improved.’ provide them with accurate, timely Th e mistrust in local authorities information during floods, a new such as Council may have stemmed survey shows. from the unreliable information lo- And the results suggest that a size- cals received during the fl oods as- able majority of locals support meas- sociated with Cyclone Debbie last ures such as dredging, the removal of March. rock walls and new ocean outfalls to reduce the future fl ood risk. Confl icting info Th e survey, conducted by Byron Nearly 65 per cent of respondents Council to help it develop a fl ood said they had received confl icting risk management plan, found that information about fl oods in the past. Mullumbimby Public School students were excited to have crews from the Westpac Rescue Helicopter Service only the State Emergency Services ‘No-one was able to give me in- and the Little Ripper Drone Patrol drop-in for a visit on Friday. -

![Wolf Creek by Sonya Hartnett [Book Review]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0496/wolf-creek-by-sonya-hartnett-book-review-2040496.webp)

Wolf Creek by Sonya Hartnett [Book Review]

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Ryan, Mark (2011) Wolf Creek by Sonya Hartnett [Book Review]. Senses of Cinema, 2011(61), pp. 1-2. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/48070/ c Consult author(s) regarding copyright matters This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// www.sensesofcinema.com/ 2011/ book-reviews/ wolf-creek-by-sonya-hartnett/ Wolf Creek by Sonya Hartnett review by Mark David Ryan Mark David Ryan is a Lecturer in Film and Television for the Creative Industries Faculty, Queensland University of Technology and an expert on Australian horror films. -

Western Electric: a Survey of Recent Western Australian Electronic Music

Edith Cowan University Research Online Sound Scripts 2005 Western Electric: A survey of recent Western Australian electronic music Lindsay Vickery Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/csound Part of the Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, and the Music Commons Refereed papers from the Inaugural Totally Huge New Music Festival Conference, This Conference Proceeding is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/csound/5 Western Electric: A survey of recent Western Australian electronic music Lindsay Vickery La Salle-SIA College of the Arts, Singapore Abstract This paper surveys developments in recent Western Australian electronic music through the work of a number of representative artists in a range of internationally recognised genres. The article follows specific cases of practitioners in the fields of Sound Art (Alan Lamb and Hannah Clemen), live and interactive electronics (Jonathan Mustard and Lindsay Vickery) and noise/lo-fi electronics (Cat Hope and Petro Vouris) and glitch/electronica (Dave Miller and Matt Rösner). Like all Australian states Western Australia has a comparatively large land mass which has developed a highly centralized population (over 75% of inhabitants) in its capital city Perth. As a result this paper is principally a survey of recent activity in Perth, rather than the whole state. Perth is also rather peculiar, being a medium-sized city (roughly 1.5 million) that is separated from other similarly sized centres by four to five hours by air. This paper will consider some of the possible effects of this isolation in the context of the development of a range of practices and methods in electronic music that reflect similar directions elsewhere in the world. -

Prejudicial Publicity: Victoria and New South Wales Compared

2018 Restraining ‘Extraneous’ Prejudicial Publicity 1263 RESTRAINING ‘EXTRANEOUS’ PREJUDICIAL PUBLICITY: VICTORIA AND NEW SOUTH WALES COMPARED JASON BOSLAND* This article explores the powers available to courts in Victoria and New South Wales to restrain the media publication of ‘extraneous’ prejudicial material – that is, material that is derived from sources extraneous to court proceedings rather than from the proceedings themselves. Three sources of power are explored: the power in equity to grant injunctions to restrain threatened sub judice contempt, the inherent jurisdiction of superior courts and, finally, statutory powers in New South Wales under the Court Suppression and Non-publications Orders Act 2010 (NSW) and in Victoria under the Open Courts Act 2013 (Vic). It argues that the approach of the Victorian courts is much broader in terms of the scope and application of orders, which potentially explains why orders restraining extraneous material are more commonly made in Victoria than in New South Wales. It further argues that the Victorian approach presents some significant consequences for publishers. I INTRODUCTION The right to a fair trial is ingrained in the common law.1 It is also recognised as a fundamental human right,2 and, in some jurisdictions, as an express constitutional guarantee.3 According to the law, one of the ways that the right to * Associate Professor, Melbourne Law School, University of Melbourne; Co-Director, Centre for Media and Communications Law (CMCL), University of Melbourne. The author wishes to thank the staff of Melbourne Law School’s Law Research Service, especially Robin Gardner, Louis Ellis and Kirsten Bakker. Thanks also to Jonathan Gill and Vicki Huang for helpful advice, and to Tim Kyriakou, Claire Richardson and James Roberts for outstanding research assistance. -

Polonia in Australia

1PMPOJBJO"VTUSBMJB $IBMMFOHFTBOE1PTTJCJMJUJFTJOUIF/FX.JMMFOOJVN &MJ[BCFUI%SP[EBOE%FTNPOE$BIJMM POLONIA IN AUSTRALIA CHALLENGES AND POSSIBILITIES IN THE NEW MILLENNIUM Australian-Polish Community Services, Melbourne POLONIA IN AUSTRALIA: CHALLENGES AND POSSIBILITIES IN THE NEW MILLENNIUM Edited by Elizabeth Drozd and Desmond Cahill This book is published at theLearner.com a series imprint of the UniversityPress.com First published in Australian in 2004 by Common Ground Publishing Pty Ltd PO Box 463 Altona Vic 3018 ABN 66 074 822 629 In association with Australian-Polish Community Services Inc. 77 Droop Street Footscray Vic 3011 www.theLearner.com Selection and editorial matter copyright © Australian-Polish Community Services Inc. 2004 Individual chapters © individual contributors 2004 All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data: Where to Now? Polonia in Australia Conference 2003 : Moonee Ponds, Vic.). Australian-Polish Community Services Inc.: Polonia in Australia: challenges and possibilities in the new millennium ISBN 0 95779 745 1 ISBN 0 95779 746 X. (PDF) 1. Polish Australians - Services for - Congresses. 2. Polish Australians - Public welfare - Congresses. 3.Polish Australians - Social conditions - Congresses. I. Drozd, Elizabeth. II. Australian-Polish Community Services. III. Title. IV. Title: Polonia in Australia: challenges and possibilities in the new millennium. V. Title: Papers from the Where to Now? Polonia in Australia Conference. VI. Title: Polonia in Australia : challenges and possibilities in the new millennium. -

Download the Milat Letters: the Inside Story from the Backpacker Murderer Free Ebook

THE MILAT LETTERS: THE INSIDE STORY FROM THE BACKPACKER MURDERER DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Alistair Shipsey | 274 pages | 07 Nov 2014 | Alistair Shipsey | 9780992497750 | English | United States BIOGRAPHY NEWSLETTER They say he had someone or others with him which we will never kw. You know the saying: There's no time like the present Nineteen-year-old Gibson was found in the fetal position riddled with stab wounds so deep that his spine had been severed and lungs punctured. Share this article Share. Item location:. Report a bad ad experience. Alistair Shipsey. He has been on hunger strikes, Even cut off his finger and wrapped it in paper And put it in an envelope addressed To the judge who has been rejecting his appeal Applications as he protests his innocence. Rod Milton. The shocking claims form part of his book The Milat Lettersself The Milat Letters: The Inside Story from the Backpacker Murderer in Australia last year and due for release in the UK at the end of the month. Related sponsored items Feedback on our suggestions - Related sponsored items. I ate it one handed. Passengers chant 'Off off off! Milat was recently diagnosed with oesophageal cancer and has been spending the remainder of his days in the medical ward of Long Bay jail undergoing chemotherapy. Britons living under Tier-3 lockdown rules will NOT get refunds for holiday and flights - but could be May 31, Chantal rated it did not like it. They had planned to meet friends, but never arrived. This book is just a compilation of the letters Ivan Milat wrote his nephew. -

Caged Untold

Contents US V�S THEM =ANTI- AUTHORITARIAN WAYS. WHEN AND WHERE DID IT ALL BEGIN. A BRIEF SUMMARY AND HISTORY OF INMATE 43517. I was made a ward of the state 11 August 1986. Graduate to the Big House �Pentridge� A fresh 17yr old kid.� 28th DECEMBER 1986 TRANSFERRED TO H- DIVISION. RELEASED 9 APRIL 1988; I WAS RELEASED FULL OF HATE AND RAGE. IT�S YOUR TURN F*CKER YOUR DOSE NOW! GAME ON. ARRESTED 8 JULY 1988. �EGGSCELL-LENT, SPLAT!� ROCKED! Hate all those who hate you. To Hate them even more and become their f*cking nightmare! You gotta be lucky every day. I only gotta be lucky ONCE! CONTRARY TO WHAT MATHEW THOMPSON CLAIMS IN HIS FALSIFIED CRIME FICTION NOVEL �MAYHEM�, I HAVE NEVER EVER APPLIED SEMEN IN ANY OF MY BRONZE UP MIXS PERIOD! RELEASED FULL OF HATE AND RAGE. ARRESTED 27 OCTOBER 1989; CAB RIDE! I still kept going. No surrender Eat Shit and Die. Us V�s Them. Green/ Blue at its best in full on warfare. �YOU GOTTA BE LUCKY EVERY DAY, I ONLY GOTTA BE LUCKY ONCE!� The chief was now on sick leave popping sara packs as if they were tic- tacs! (ADVERSARIAL) the Me V�s The System. Who cares a f*ck! I don�t, nor the others. A �LOW� P.O. SOLJA�S ROLL CALL! 10 JANUARY 199, RELEASED FROM H- DIVISION: CRAZY MAD AND REAL F*CKING BAD! ME V�S THEM.) YES! COME CATCH ME COPPER! 20 MAY 1991.ARRESTED BY ARMED HOLD UP SQUAD/ BASHED. -

A Study Guide by Marguerite O'hara

© ATOM 2014 A STUDY GUIDE BY MARGUERITE O’HARA http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-533-9 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au CONTENTS 2 CURRICULUM GUIDELINES 3 THE CRIME GENRE 5 MAP OF THE AREA 6 CAST AND CREW 7 PRE-VIEWING ACTIVITY 7 SYNOPSIS 7 STUDENT ACTIVITIES: WATCHING, REFLECTING AND RESPONDING 11 RESOURCES AND REFERENCES CURRICULUM GUIDELINES Catching Milat is a dramatic reconstruction of how mem- bers of the NSW Police Department tracked down and secured the conviction of a notorious killer Ivan Milat. His murderous spree took place over a number of years in the early 1990s. While the film does show something of how Milat is thought to have operated and managed to escape detection for some years, the program is more concerned with the police enquiry (catching Milat); how the investigat- ing team were able to link his movements and behaviour to the murders through a meticulous process of gathering INTRODUCTION evidence and following up earlier leads. Catching Milat is a two-part drama based on the events surrounding the investigation that led to the arrest and conviction of serial killer Ivan Milat. Most characters play the roles of actual people, but certain events and charac- ters have been created or changed for dramatic effect. Incorporating stylised flashbacks and archival footage, Catching Milat is a television mini-series that returns viewers to a time when backpacking was a rite-of-pas- sage for young people eager to explore the world. Ivan Milat was arrested in 1994. Catching Milat is the story of the men who brought him to justice.