Heterogeneous Networks in Three New South Wales Local Government Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Infrastructure Funding Performance Monitor

UDIA NSW | 2020 Infrastructure Funding Performance Monitor $2.7 billion is currently held as a restricted asset by Councils for the delivery of infrastructure • The current total balance of contributions held across the Greater Sydney megaregion is $2.7 billion, with the average amount held by a Council sitting at $56 million. • Every year new housing contributes almost $900 million to local infrastructure, Executive roads, stormwater, open space and community facilities across the Greater Sydney megaregion through the infrastructure charging framework. It is expected Summary that this infrastructure is built with the funds that are paid. • However, only 64% of the contributions that are paid for were spent in the last three years. Average Total Expenditure Total Income Balance E/I ($’000) ($’000) ($’000) Total 0.64 $650,679 $876,767 $2,653,316 Contributions Under a s7.11 0.85 $564,670 $711,912 $2,330,289 or s7.12 Under a s7.4 0.62 $41,640 $124,180 $259,501 The amount of unspent funding has increased over the past three years • Since FY16 total unspent contributions have increased 33% from $1.98 billion to over $2.65 billion. Executive • In the last year alone unspent contributions increased by 7.8%, or almost $191 million. Summary • Local Government must resolve local issues to ensure that infrastructure is actually provided on the ground. If necessary, the State Government should step-in to support Councils get infrastructure on the ground. Increased funding does not correlate to increased infrastructure delivery • The scatter graphs here show an extremely weak relationship between cash held and expenditure ratios. -

Amendment Regulation 2021 Under the Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997

New South Wales Protection of the Environment Operations (Clean Air) Amendment Regulation 2021 under the Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997 Her Excellency the Governor, with the advice of the Executive Council, has made the following Regulation under the Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997. MATT KEAN, MP Minister for Energy and Environment Explanatory note The objects of this Regulation are as follows— (a) to provide for different levels of control of burning in local government areas, including for the Environment Protection Authority and local councils to approve burning in the open, (b) to update references to local government areas following the amalgamation of a number of areas. This Regulation is made under the Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997, including section 323 (the general regulation-making power) and Schedule 2. Published LW 1 April 2021 (2021 No 163) Protection of the Environment Operations (Clean Air) Amendment Regulation 2021 [NSW] Protection of the Environment Operations (Clean Air) Amendment Regulation 2021 under the Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997 1 Name of Regulation This Regulation is the Protection of the Environment Operations (Clean Air) Amendment Regulation 2021. 2 Commencement This Regulation commences on the day on which it is published on the NSW legislation website. Page 2 Published LW 1 April 2021 (2021 No 163) Protection of the Environment Operations (Clean Air) Amendment Regulation 2021 [NSW] Schedule 1 Amendment of Protection of the Environment Operations (Clean Air) Regulation 2010 Schedule 1 Amendment of Protection of the Environment Operations (Clean Air) Regulation 2010 [1] Clause 3 Definitions Omit “Cessnock City”, “Maitland City” and “Shoalhaven City” from paragraph (e) of the definition of Greater Metropolitan Area in clause 3(1). -

Seven Unveils Content Plans for 2019

SEVEN UNVEILS CONTENT PLANS FOR 2019 Slate includes new Bevan Lee drama and two supersized reality hits Geraldine Hakewill, Joel Jackson and Catherine McClements headline Miss Fisher spin-off MKR’s 10th anniversary season to launch the year “Top Gear meets food” in new Gordon Ramsay series New overseas dramas feature screen heavyweights Martin Clunes, Sheridan Smith, Kelsey Grammer and more (Sydney, Friday October 26): The Seven Network today unveiled its content plans for 2019. Four new local dramas, including the next offering from creator Bevan Lee; two supersized reality hits; a female spinoff to one of the year’s most heart-warming hits and the landmark 10th season of one of Australia’s biggest shows are just some of the programs set to take Seven into its 13th consecutive year of leadership. Commenting, Seven’s Director of Network Programming Angus Ross said: “After a close win last year, we promised to up our game in 2018, and the team has delivered in spades. We’ve broken records and dominated the ratings throughout the year. In fact, in every month we have never dropped below a 39% share, while our competitors have never been above 39%. Our worst is still better than their best. “What’s particularly pleasing is that this success is down to the strength and depth of our programming across the board. From 6am to midnight, we have the strongest spine of ratings winners, bar none. And with the AFL and Cricket locked up until 2022, Seven can guarantee those mass audiences, and certainty for our advertisers, for years to come.” NEW TO SEVEN IN 2019 BETWEEN TWO WORLDS From Australia’s most prolific creator/writer Bevan Lee (Packed to the Rafters, A Place To Call Home, All Saints, Winners & Losers, Always Greener) comes an intense, high concept contemporary drama series about two disparate and disconnected worlds, thrown together by death and a sacrifice in one and the chance for new life in the other. -

Valley Walk Great Burragorang

THE Great Burragorang Valley Walk Connecting the Blue Mountains, Wollondilly and the Southern Highlands In Partnership With Contents The Great Burragorang Valley Walk page 3 Proposed Walk page 4 Places of Interest page 6 Community Benefits page 7 Estimated Investment page 8 Buxton Plateau by photographer Petar B Cover – Lake Burragorang by photograper John Spencer 2. THE Great Burragorang Valley Walk The Great Burragorang Valley Walk is a truly unprecedented opportunity to connect three neighbouring Councils, their communities, towns and villages. This Council collaboration will highlight iconic areas of unique natural beauty including the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Areas, National Parks and conservation areas. The potential for The Great Walk to become a leading attraction is enormous, enabling both community and visitors to enjoy and appreciate this immense natural landscape with its abundance of Australian native flora and fauna. Through a partnership led by Wollondilly Shire Council and in conjunction with Blue Mountains Council and Wingecarribee Shire Council, the Great Walk initiative is an opportunity to connect our communities, attract visitors and tourism, grow the local and regional economy and ensure our environment and heritage is valued and protected. The Great Walk will offer a setting to attract small group-guided tours and self-guided tours across a series of designated stages to suit individual experience and ability. Walk and nature enthusiasts can choose from a selection of shorter day walks or overnight experiences. With a variety of start and finish points in close proximity to Sydney, Wollongong and the Illawarra, the Southern Highlands, Western Sydney, Western Sydney International Airport, Macarthur and Canberra there are easy access points from major roads, making the area accessible to large populations. -

Wingecarribee Shire Council Impending ISDN Termination Forced Urgent Action for Local Council

Case Study: Wingecarribee Shire Council Impending ISDN termination forced urgent action for local council Impending termination of ISDN lines forced urgent action for Wingecarribee Shire Council. The Council needed to replace the PBX, and also wanted to take advantage of the many features and benefits of the Cloud. After a competitive procurement process, the Council engaged CommsChoice to review the range of available IP solutions. As the Council was already operating Microsoft Office 365 it was determined that the CommsChoice Direct Routing for Microsoft Teams application on Office 365 was the most suitable solution. Situation Wingecarribee Shire Council (WSC) was earmarked to have The services its ISDN services decommissioned in late 2019. Unfortunately, a offered by change in IT management at a critical point in time resulted in CommsChoice the connection details being overlooked. have been It was only when a final disconnection notice was issued “ flawless, and their regarding the impending termination of the Council’s ISDN lines project and sales that the issue came to the attention of the IT team. teams have been This impending termination forced rapid action. fantastic. John Crawford, Chief Information Officer, Wingecarribee Shire John Crawford, Chief Information Officer, Council (the Council or WSC) said the Council had previously Wingecarribee Shire Council been using an older generation PBX that was not capable of carrying IP voice. ” “We were forced to look at which of the available options could be implemented within a tight time frame, and also took the opportunity to identify a wish list of things we wanted from a new solution. We wanted a tool that enabled better collaboration, something to fit with the Microsoft suite, a solution that enabled video conferencing between sites, mobility, and to increase our Disaster Recovery capability. -

Annual Report 2018/19

ANNUAL REPORT 2018/19 CreateWOLLONDILLY “Growth, development and change is inevitable and much of the time, out of our control. What we can control is how we respond to it and the direction that it takes. The challenge for Wollondilly's future will be 'balance' between the past, the present and the future. Wollondilly is unique. It is Sydney's water bowl and a large part of its food bowl. It's a beautiful rural setting and rural lifestyle with towns and villages, a strong sense of community, a rich and diverse environment including green space, rolling hills, rivers, lakes, mountains, heritage and agriculture. The challenge for Wollondilly will be the preservation of these treasured aspects of living in our Shire. I want our future generations to still have these views, to enjoy what we have now and what we possibly take for granted. Once it's gone, it's gone. You can't get it back.” Karen Burgess, Winner of the Create Wollondilly 2033 Art Competition (16 years and older category) 2 | WOLLONDILLY SHIRE COUNCIL ANNUAL REPORT 2018/19 | 3 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Acknowledgement of the Original Custodians 8 1.2 We are Wollondilly 9 1.3 Message from the Mayor and CEO 10 1.4 Your Councillors and Wards 12 1.5 Our Vision, Mission and Values 16 1.6 Organisational Structure 18 1.7 Service Delivery in a Growing Shire 21 1.8 What Council Delivers to the Community - Service Overview 22 2. COUNCIL PERFORMANCE 2.1 The Integrated Planning and Reporting Framework and Annual Report 27 2.2 Community Satisfaction with Council Services 28 2.3 Summary of Council’s Overall Annual Performance 32 2.4 Measuring Performance – Overall Performance by Strategic Theme 33 Theme 1: Sustainable and Balanced Growth 35 Theme 2: Management and Provision of Infrastructure 43 Theme 3: Caring for the Environment 49 Annual Re port Theme 4: Looking after the Community 55 Theme 5: Effective and Efficient Council 63 3. -

Privatization Examining the Potential Solutions to FAA Reform

Summer 2015 | VOLUME 57, NO. 2 Privatization Examining the Potential Solutions to FAA Reform Plus • A Cost-Effective Approach to ATM Modernization • The Career of Nevil Shute Norway • Remote Tower Systems – A Domestic and International Conversation JMA Solutions is a pioneering government contractor • Air Traffic Management whose primary focus is Program Management, • Engineering Services Engineering Services, Financial and Air Traffic • Financial Management Management. JMA is committed to meeting customer • Curriculum Development and Design requirements and exceeding expectations by providing • Conference Planning knowledgeable, seasoned professionals who offer exceptional service and support to our government • Safety Management & Information Assurance clients. Our commitment to excellence and unparalleled • Strategic Management & Planning customer service has earned us a proven track record of • Web Development & Graphic Design successfully delivering outstanding results. Service Disabled Veteran 8(a) Certified Twitter/JMA_Solutions YouTube / The JMASolutions LinkedIn / jma-solutions Woman Owned Small Business 600 Maryland Ave. SW, Suite 400 E, Washington, D.C. 20024 • Phone: 202-465-8205 • www.jma-solutions.com ATCA members and subscribers have access to the online edition of The Journal of Air Traffic Control. Visit lesterfiles.com/ pubs/ATCA. Password: ATCAPubs (case Contents sensitive). Summer 2015 | Vol. 57, No. 2 Articles Published for: 09 Managed Services Air Traffic Control Association 1101 King Street, Suite 300 A Cost-Effective -

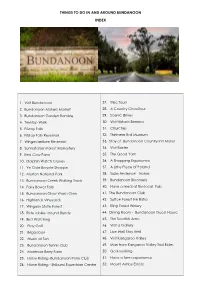

Things to Do in and Around Bundanoon Index

THINGS TO DO IN AND AROUND BUNDANOON INDEX 1. Visit Bundanoon 27. Trike Tours 2. Bundanoon Makers Market 28. A Country Chauffeur 3. Bundanoon Garden Ramble 29. Scenic Drives 4. Treetop Walk 30. Visit Historic Berrima 5. Fitzroy Falls 31. Churches 6. Fitzroy Falls Reservoir 32. Thirlmere Rail Museum 7. Wingecarribee Reservoir 33. Stay at Bundanoon Country Inn Motel 8. Sunnataram Forest Monastery 34. Visit Exeter 9. Red Cow Farm 35. The Good Yarn 10. Dolphin Watch Cruises 36. A Shopping Experience 11. Ye Olde Bicycle Shoppe 37. A Little Piece of Poland 12. Morton National Park 38. Suzie Anderson - Home 13. Bundanoon Creek Walking Track 39. Bundanoon Bloomery 14. Fairy Bower Falls 40. Have a meal at the local Pub 15. Bundanoon Glow Worm Glen 41. The Bundanoon Club 16. Highlands Vineyards 42. Sutton Forest Inn Bistro 17. Wingello State Forest 43. Eling Forest Winery 18. Ride a bike around Bundy 44. Dining Room - Bundanoon Guest House 19. Bird Watching 45. The Scottish Arms 20. Play Golf 46. Visit a Gallery 21. Brigadoon 47. Live Well Stay Well 22. Music at Ten 48. Visit Kangaroo Valley 23. Bundanoon Tennis Club 49. Man from Kangaroo Valley Trial Rides 24. Montrose Berry Farm 50. Go Kayaking 25. Horse Riding -Bundanoon Pony Club 51. Have a farm experience 26. Horse Riding - Shibumi Equestrian Centre 52. Mount Ashby Estate 1. VISIT BUNDANOON https://www.southern-highlands.com.au/visitors/visitors-towns-and-villages/bundanoon Bundanoon is an Aboriginal name meaning "place of deep gullies" and was formerly known as Jordan's Crossing. Bundanoon is colloquially known as Bundy / Bundi. -

The Old Hume Highway History Begins with a Road

The Old Hume Highway History begins with a road Routes, towns and turnoffs on the Old Hume Highway RMS8104_HumeHighwayGuide_SecondEdition_2018_v3.indd 1 26/6/18 8:24 am Foreword It is part of the modern dynamic that, with They were propelled not by engineers and staggering frequency, that which was forged by bulldozers, but by a combination of the the pioneers long ago, now bears little or no needs of different communities, and the paths resemblance to what it has evolved into ... of least resistance. A case in point is the rough route established Some of these towns, like Liverpool, were by Hamilton Hume and Captain William Hovell, established in the very early colonial period, the first white explorers to travel overland from part of the initial push by the white settlers Sydney to the Victorian coast in 1824. They could into Aboriginal land. In 1830, Surveyor-General not even have conceived how that route would Major Thomas Mitchell set the line of the Great look today. Likewise for the NSW and Victorian Southern Road which was intended to tie the governments which in 1928 named a straggling rapidly expanding pastoral frontier back to collection of roads and tracks, rather optimistically, central authority. Towns along the way had mixed the “Hume Highway”. And even people living fortunes – Goulburn flourished, Berrima did in towns along the way where trucks thundered well until the railway came, and who has ever through, up until just a couple of decades ago, heard of Murrimba? Mitchell’s road was built by could only dream that the Hume could be convicts, and remains of their presence are most something entirely different. -

Emily O'grady Thesis

Subverting the Serial Gaze: Interrogating the Legacies of Intergenerational Violence in Serial Killer Narratives Emily O’Grady Bachelor of Fine Arts (Honours) Creative Industries: Creative Writing and Literary Studies Queensland University of Technology Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 1 Abstract This thesis subverts, disrupts and reimagines dominant narratives of fictional serial crime through a hybrid research paradigm of creative practice and critical analysis. The creative output of this thesis is an 80,000 word literary novel titled The Yellow House, accompanied by a 20,000 word critical exegesis. In the following, I argue that current fictional iterations of the serial killer literary genre are rigidly conservative, and remain fixed within the safe confines of genre conventions wherein the narrative bears little resemblance to how abject violence and the aftermath of serial crime plays out in real life. The broad framework of genre theory, accompanied by trauma theory, allows for an examination of the serial killer genre to identify the space in which my creative practice—an Australian, literary rendering of serial crime—fits as an extension and subversion of the genre. By reimagining the Australian serial killer narrative, I seek to challenge the reductive serial killer genre, and come to a potential offering of serial homicide that interrogates how the legacies of abject violence can be transmitted across generations. I do this by shifting the focus onto the aftermath of the crime and its numerous victims—in particular, the descendants of serial killers. The Yellow House presents a destabilising fictionalisation of serial crime that disrupts the conventions of the genre in order to contend with the complexity and instability of serial homicide. -

SWT 2003-04 Areport.Indd

2003 – 2004 Annual Report INVESTING IN CONTENT / FOR WORLD SCREENS VISION To lead the West Australian screen industry to a level of creative and commercial success which is a source of pride and opportunity for all Western Australians. SCREENWEST’S ROLE ScreenWest’s role as described in its Constitution is to: • Encourage and promote the development of the Western Australian screen industry encompassing every aspect of filmmaking. • Administer financial and other assistance provided by the Government of Western Australia or other public. • Assist with the development of film scripts and film projects for production in Western Australia. • Encourage a viable and diverse screen culture in Western Australia including the promotion of Western Australian film projects, practitioners, issues, exhibitions and facilities. • Develop an awareness of the Western Australian film industry on a national and international level and assist practitioners in the Western Australian film industry to a national and international focus. • Keep itself informed of new technological developments in all aspects of filmmaking and assist practitioners in the Western Australian film industry in expanding their technical, professional and creative skills. ScreenWest considers its role is to work with the screen industry to develop relationships with key strategic partners and create new initiatives in order to expand and strengthen the WA screen industry. Accordingly, ScreenWest is identifying new market opportunities, providing incentive funding and identifying skill -

180227 NCC Live Music Strategy

SUBJECT: 27/02/18 – Newcastle City Council Live Music Strategy COUNCILLORS: Cr Nelmes; Cr Clausen; Cr Dunn; Cr Byrne; Cr Winney Baartz; Cr Duncan; Cr White MOTION That Newcastle City Council: 1. Notes that the City of Newcastle has a proud and rich history of celebrating and promoting live music; 2. Notes that the City of Newcastle's night time economy is now worth $1.4 billion and employs over 12,000 people, including many in the live music industry; 3. Supports the creation of a Newcastle Local Live Music Industry Advisory Group to advise all three tiers of government on policy development aimed at supporting the growth and sustainability of Newcastle's live music industry; 4. Embeds a commitment to a vibrant live music scene in the next iteration of the Community Strategic Plan (CSP) and works to finalise the draft Newcastle After Dark Nighttime Economy Strategy, including a detailed Live Music Strategy, guided by best practice local government principles for live music policy as developed by the New South Wales Government's Live Music Office; and 5. Develops a process to make available Council owned venues like the Civic Playhouse and City Hall Banquet Room for in-kind use on certain days by live music providers catering for all-ages gigs. BACKGROUND Recently, live music industry professionals, artists, venue operators and music industry businesses have raised a number of concerns about the future of the live music industry in Newcastle. The NSW Government's Live Music Office has identified a number of initiatives that can be implemented in the short, medium to long term to protect, support and grow the live music industry across Newcastle.