Understanding Polarization in Responses to Genocidal Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Colonial Genealogy of Violence Against Tutsi Women in The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Gender-Based Violence and Submerged Histories: A Colonial Genealogy of Violence Against Tutsi Women in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Gender Studies by Helina Asmelash Beyene 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Gender-Based Violence and Submerged Histories: A Colonial Genealogy of Violence Against Tutsi Women in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide by Helina Asmelash Beyene Doctor of Philosophy in Gender Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Sondra Hale, Chair My dissertation is a genealogical study of gender-based violence (GBV) during the 1994 Rwandan genocide. A growing body of feminist scholarship argues that GBV in conflict zones results mainly from a continuum of patriarchal violence that is condoned outside the context of war in everyday life. This literature, however, fails to account for colonial and racial histories that also inform the politics of GBV in African conflicts. My project examines the question of the colonial genealogy of GBV by grounding my inquiry within postcolonial, transnational and intersectional feminist frameworks that center race, historicize violence, and decolonize knowledge production. I employ interdisciplinary methods that include (1) discourse analysis of the gender-based violence of Belgian rule and Tutsi women’s iconography in colonial texts; (2) ii textual analysis of the constructions of Tutsi women’s sexuality and fertility in key official documents on overpopulation and Tutsi refugees in colonial and post-independence Rwanda; and (3) an ethnographic study that included leading anti gendered violence activists based in Kigali, Rwanda, to assess how African feminists account for the colonial legacy of gendered violence in the 1994 genocide. -

We Are All Rwandans”

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “We are all Rwandans”: Imagining the Post-Genocidal Nation Across Media A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television by Andrew Phillip Young 2016 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION “We are all Rwandans”: Imagining the Post-Genocidal Nation Across Media by Andrew Phillip Young Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Chon A. Noriega, Chair There is little doubt of the fundamental impact of the 1994 Rwanda genocide on the country's social structure and cultural production, but the form that these changes have taken remains ignored by contemporary media scholars. Since this time, the need to identify the the particular industrial structure, political economy, and discursive slant of Rwandan “post- genocidal” media has become vital. The Rwandan government has gone to great lengths to construct and promote reconciliatory discourse to maintain order over a country divided along ethnic lines. Such a task, though, relies on far more than the simple state control of media message systems (particularly in the current period of media deregulation). Instead, it requires a more complex engagement with issues of self-censorship, speech law, public/private industrial regulation, national/transnational production/consumption paradigms, and post-traumatic media theory. This project examines the interrelationships between radio, television, newspapers, the ii Internet, and film in the contemporary Rwandan mediascape (which all merge through their relationships with governmental, regulatory, and funding agencies, such as the Rwanda Media High Council - RMHC) to investigate how they endorse national reconciliatory discourse. -

RSE | Listing Energicotel on The

PRESS RELEASE: ENERGICOTEL ‘ECTL’ PLC CORPORATE BOND LISTING ON THE RWANDA STOCK EXCHANGE. TODAY, ENERGICOTEL PLC or ‘ECTL’ by trading name officially listed its First Tranche of the FRW 6,500,000,000 Long-term Fixed Rate Corporate Bond amounting to FRW 3,500,000,000 on the Rwanda Stock Exchange Bond Market. Rwanda’s Ministry of Infrastructure, Honorable Ambassador Claver Gatete, rang the bell to grace the occasion and mark commencement of ECTL trading on the RSE.The listing event marked yet another milestone especially this time as the Exchange celebrates its 10 years of operations. ECTL listing is particularly significant as ENERGICOTEL PLC becomes the first company among 12 SMEs under the 1st cohort of the capital market investment clinic project to raise funds and list its securities on the the stock exchange. By the same token, the company also becomes the first company in the energy sector to join the stock market. Presiding over the launch of the listing and trading of ENERGICOTEL PLC’s Corporate Bond, the Minister of Infrastructure Amb. Claver Gatete came back on the role of the Government of Rwanda in the development of the capital market where it uses the market for issuances. “By issuing treasury bonds to the public and privatizing a few of its own companies through the market, the Government has shown a good example to the private sector to follow suit”. The Minister also commended ENERGICOTEL PLC for taking the bold decision to be a pioneer in the energy sector to use capital market in issuing its maiden corporate bond. -

The Challenges of Emerging Stock Markets in Africa, a Case of Rwanda

East African Journal of Science and Technology, Vol.5, Issue 1, 2015 THE CHALLENGES OF EMERGING STOCK MARKETS IN AFRICA, A CASE OF RWANDA STOCK EXCHANGE Wilson KAZARWA The Independent Institute of Lay Adventists of Kigali, Box 6392, Kigali Rwanda E-mail: , Abstract A number of studies previously carried out indicate that capital market development of any economy is synonymous with the growth and economic development, and almost every African country has put an effort to establish a stock market, including Rwanda. This study focuses on the challenges faced by emerging stock markets in Africa, a case study of Rwanda Stock Exchange. The main objectives of this study include establishing the types of securities traded, rules governing the market, challenges facing the market and the suggested recommendations to counter these challenges. A population comprising of five listed companies and the Capital Market Authority were considered and in each case, one respondent was selected using purposive sampling technique. Although this research used more of secondary data that was obtained through literature review, primary data was also collected using an interview guide. The study has found that currently, the types of securities traded include three government bonds and one corporate bond, and stocks from five companies that have listed and cross-listed on the market. The study established that rules are provided and well adhered to and challenges facing the market include among others the general public which is not fully knowledgeable about trading in stocks, coupled with less skilled investment experts and lacking long-term credit, all this reduce profitability and thus limit the chances of listing stocks onto the stock market. -

Topic: Share Price Change and Investment Decision On

COLLEGE OF BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS (CBE) TOPIC: SHARE PRICE CHANGE AND INVESTMENT DECISION ON THE RWANDA STOCK EXCHANGE (2011 – 2016) Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the Degree of Masters of Business Administration specialized in Finance. Submitted by: KANSIIME Gloria Supervisor: Dr. BARAYANDEMA Jonas June, 2018 I DECLARATION I declare that an evaluation of SHARE PRICE CHANGE AND INVESTMENT DECISION ON THE RWANDA STOCK EXCHANGE IN RWANDA is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. KANSIIME Gloria Reg. No: 214003207 MBA-Finance Signature: ……………………………………Date:……../……/2018 I certify that this project entitled “Share price change and investment decision on RSE” was carried out under my supervision. Supervisor name: Dr. BARAYANDEMA Jonas Signature………………………Date:……../………/2018 i COLLEGE OF BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS (CBE) Approval Sheet This thesis entitled SHARE PRICE CHANGE AND INVESTMENT DECISION ON THE RWANDA STOCK EXCHANGE IN RWANDA written and submitted by KANSIIME Gloria In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of finance is hereby accepted and approved. Supervisor Dr. BARAYANDEMA Jonas …………………………………… Date: ……………………… Member of the Jury Member of the Jury Dr. MUSEKURA Celestine Dr. BUSORO R. Theodore …………………………… …………………………… Date: ……………………… Date: ………………… Director of Graduate Studies Dr. NDIKUMANA Philippe ………………………………… Date ………………………… ii DEDICATION First and foremost, I dedicate my work to my beloved Aunt who toiled for my education and sacrificed the descent life they deserved to make sure I attained a bachelor’s degree without which I could not have enrolled for this Master’s Degree program. -

Assessing the Contribution of Military in Peace Building in Africa: Case Study Rwanda (1994-2016)

UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI INSTITUTE OF DIPLOMACY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES ASSESSING THE CONTRIBUTION OF MILITARY IN PEACE BUILDING IN AFRICA: CASE STUDY RWANDA (1994-2016) MPAGAZE Anthony Baguma Reg. No: R47/8917/2017 SUPERVISOR: Col (Dr) Steven HANDA RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR THE AWARD OF POST GRADUATE DIPLOMA IN STRATEGIC STUDIES. DECEMBER 2018 DECLARATION This research project is my own original work and it has never been presented for examination in any other university or any other award. All materials from other sources have been acknowledged appropriately. Name: MPAGAZE Anthony BAGUMA Registration No: R47/8917/2017 Signature: ___________________________ Date: ___________________________ The project has been submitted for examination with our approval as the University Supervisor. Name: Dr Steven HANDA Signature: ___________________________Date: _____________________________ i DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my beloved parents for their guidance ever since my childhood which became a strong base that propelled me to undertake this academic journey. My success is built on the foundation you gave me. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank God for the gift of life given into me throughout this course. Secondly I wish to pay special tribute to my family especially my wife Susan Asiimwe and our children, Nyemina Jordan, Beza Georgia and Mpagaze Josh for their understanding, sacrifice, perseverance, patience and moral support given to me during the course. I pledge to dedicate more time to them in the future. I wish to extend my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Steven HANDA without his intellectual guidance and support it would have been difficult to complete this task. -

The Republic of Rwanda Us$620000000

THE REPUBLIC OF RWANDA U.S.$620,000,000 5.500 per cent. Notes due 2031 Issue Price: 100 per cent. The issue price of the U.S.$620,000,000 5.500 per cent. Notes due 2031 (the “Notes”) of the Republic of Rwanda (“Rwanda”, the “Republic” or the “Issuer”) is 100 per cent. of their principal amount. Unless previously redeemed or purchased and cancelled the Notes will be redeemed at their principal amount on 9 August 2031 (the “Maturity Date”). The Notes will bear interest from 9 August 2021 at the rate of 5.500 per cent. per annum payable semi-annually in arrear on 9 February and 9 August in each year commencing on 9 February 2022. Payments on the Notes will be made in US dollars without deduction for or on account of taxes imposed or levied by the Republic of Rwanda to the extent described under “Terms and Conditions of the Notes–Taxation”. This Offering Circular does not comprise a prospectus for the purposes of Regulation (EU) 2017/1129 as it forms part of domestic law by virtue of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 (“EUWA”) (the “UK Prospectus Regulation”). Application has been made to the United Kingdom Financial Conduct Authority in its capacity as competent authority under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (as amended) (the “FCA”) for the Notes to be admitted to a listing on the Official List of the FCA (the “Official List”) and to the London Stock Exchange plc (the “London Stock Exchange”) for such Notes to be admitted to trading on the London Stock Exchange’s main market (the “Main Market”). -

Britain's Hidden Role in Rwandan State Violence

E overtly by the British and US Britain’s hidden role in governments. It is arguable that the AT civil war continued for such a ST lengthy period due primarily to the Rwandan state violence substantial Western assistance granted to both forces. Hazel Cameron explores how an idealised The final three months of the civil history of the 1994 Rwandan Genocide war coincided with the period of the BRITISH Rwandan genocide perpetrated by has provided cover for Britain’s role in Hutu extremists against the Tutsi and moderate Hutu of Rwanda. THE violence abroad. Throughout the period of the genocide, the RPA’s relationship with OF British intelligence networks tan Cohen noted how in and geopolitical concerns as well as permitted their political Stalinist Russia, ‘the past has to mutual paranoia and deep representatives to assert some Sconform to the present to ideological and cultural divisions influence in respect of the mandate establish a version of history (a (Cameron, 2011). of the United Nations Assistance master narrative) to legitimate current In 1986, the Rwandan Tutsi Mission in Rwanda (UNAMIR) at United Nations Security Council VIOLENCE policy’ (Cohen, 2001). In Rwanda, refugees in exile in Anglophone Paul Kagame has skilfully Uganda formed a rebel guerrilla discussions. The genocide and civil orchestrated a ‘master narrative’ that organisation in opposition to the war ended in Kigali in July 1994 with has resulted in the West’s selective Francophone government of the victory of the guerrilla RPA who amnesia of historical and ongoing Rwanda. Its military wing became immediately established a human rights violations perpetrated known as the Rwanda Patriotic Army Government of National Unity. -

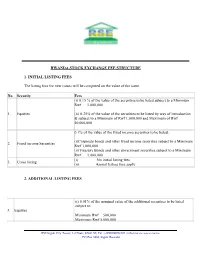

Rwanda Stock Exchange Fee Structure 1. Initial Listing

RWANDA STOCK EXCHANGE FEE STRUCTURE 1. INITIAL LISTING FEES The listing fees for new issues will be computed on the value of the issue. No. Security Fees (i) 0.15 % of the value of the securities to be listed subject to a Minimum Rwf 1,000,000 1. Equities (ii) 0.25% of the value of the securities to be listed by way of introduction & subject to a Minimum of Rwf 1,000,000 and Maximum of Rwf 50,000,000 0.1% of the value of the fixed income securities to be listed: (i)Corporate bonds and other fixed income securities subject to a Minimum 2. Fixed income Securities Rwf 1,000,000 (ii)Treasury Bonds and other government securities subject to a Minimum Rwf 1,000,000 (i) No initial listing fees 3. Cross listing (ii) Annual listing fees apply 2. ADDITIONAL LISTING FEES (i) 0.01% of the nominal value of the additional securities to be listed subject to: 3. Equities Minimum Rwf 500,000 Maximum Rwf 5,000,000 RSE Kigali City Tower, 1st Floor, KN81 ST, Tel : +(250)788516021 ; [email protected] www.rse.rw P O Box 3882, Kigali Rwanda (ii)0.05% of the value of the fixed income securities to be listed: (iii)Corporate bonds and other fixed income securities subject to a Minimum Rwf 1,000,000 4. Fixed income securities (iv) Treasury Bonds and other government securities subject to: Minimum Rwf 1,000,000 Maximum Rwf 10,000,000 The computation of the value of additional listings shall be based on the first date the securities trade ex entitlement after the additional offer. -

The Role of Stock Market on Economic Development of Rwanda; a Case Study of Rwanda Stock Exchange

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2016): 79.57 | Impact Factor (2017): 7.296 The Role of Stock Market on Economic Development of Rwanda; A Case Study of Rwanda Stock Exchange Jerome Ndagijimana1, Dr. Patrick Mulyungi2 1Student, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology 2Lecturer, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Abstract: In Rwanda there is need to provide funds to start new businesses and to expand existing businesses and industries. The stock market provides companies and the government with an avenue to raise Stock through the sale of shares and bonds to the public. The stock markets bring together those with surplus funds and those with a deficit and facilitate the exchange of the monies. This has however not gotten to its optimal level due to the following challenges facing the Rwanda stock market. First, in RSE there are a limited number of companies listed in the Rwanda Stock Exchange, the investors in Rwanda have limited investment portfolio and another challenge is the limited access to long term securities. The general objective of this study examined the role of stock market on economic development of Rwanda. This study was adopted descriptive research design. The target population of this study is 12 employees of Rwanda Stock Exchange. The researcher was used an open ended questionnaire as data collection. This means that that researcher collected the data through questionnaire. Researcher was used primary data. The Rwanda economic development has an overall correlation with stock market products of 0.776 which is strong and positive. -

The Status Quo of East African Stock Markets: Integration and Volatility

Vol. 13(5), pp. 176-187, 14 March, 2019 DOI: 10.5897/AJBM2019.8742 Article Number: 0976CEA60297 ISSN: 1993-8233 Copyright© 2019 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article African Journal of Business Management http://www.academicjournals.org/AJBM Full Length Research Paper The status quo of East African stock markets: Integration and volatility Marselline Kasiti Atenya Department of Economics, Faculty of Electrical Engineering, University of Applied Sciences, Soest in cooperation with the University of Bolton, UK. Received 16 January, 2019; Accepted 13 February, 2019 This paper presents the current stock markets’ situation of East African markets compared to Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE). The study uses weekly price indices of Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, and Uganda, South Africa as a performance benchmark for the African market. The period used is from 17th January 2008 to 31st March 2017. The stock indices’ returns results show in general that there is relatively moderate-to-low volatility. The Dar-es-Salaam stock index and the Johannesburg stock index show a higher volatility relative to the other stock market indices with the JSE showing the highest return of 0.117089 when compared to the East African market indices. The Vector Autoregressive (VAR) and Granger causality results capture the linear interdependencies among the given markets and illustrate that JSE has a low contributory impact on the returns on the East African markets. Besides, evidence shows that East African markets are independent, thus offering regional diversification benefits. However, integration is still underway. Key words: East African stock markets, stock market integration, vector autoregressive, Johannesburg stock exchange, correlation coefficient, volatility. -

Capital Structure and Company's Performance Of

CAPITAL STRUCTURE AND COMPANY’S PERFORMANCE OF LISTED COMPANIES IN RWANDA STOCK EXCHANGE, KIGALI, RWANDA KADINDA ACHENI EDWARD MBA/3793/13 A Research Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for the Requirement of the Award of the Degree of Master of Business Administration (Finance and Accounting Option) of Mount Kenya University OCTOBER 2016 i DECLARATION This research project is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other University, or for any other award. Students Name: Kadinda Acheni Edward MBA/3793/13 Sign ____________________ Date _____________ This research project has been submitted with my approval as the Mount Kenya University Supervisor Name: Mr. Osiemo Kengere Athanas Sign ____________________ Date _____________ ii DEDICATION I dedicate this study to my beloved parents, my wife and my children for allowing me to pursue my studies without pressure but rather giving me the much needed support. iii ACKNOWLEGEMENT First of all, I give glory to almighty God for his blessing in health, knowledge, determination and wisdom to cover this long journey. I would like to appreciate all the staff members of Mount Kenya University. Without their support I wouldn’t have produced this research project to the quality it deserves. Special thanks go to my supervisor who instructed and guided me throughout the writing of the research project; their advice has helped me greatly. Thanks a lot. iv ABSTRACT Choice of capital structure affects performance of firm. The general objective of the study was to assess the impact of capital structure on company performance. Specifically, the researcher sought to establish the importance of using capital structure to improve company financial performance, establish the importance of using capital structure to improve company operational performance and it contribution in risk management.