Rwanda Leveraging Capital Markets for SME Financing in Rwanda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RSE | Listing Energicotel on The

PRESS RELEASE: ENERGICOTEL ‘ECTL’ PLC CORPORATE BOND LISTING ON THE RWANDA STOCK EXCHANGE. TODAY, ENERGICOTEL PLC or ‘ECTL’ by trading name officially listed its First Tranche of the FRW 6,500,000,000 Long-term Fixed Rate Corporate Bond amounting to FRW 3,500,000,000 on the Rwanda Stock Exchange Bond Market. Rwanda’s Ministry of Infrastructure, Honorable Ambassador Claver Gatete, rang the bell to grace the occasion and mark commencement of ECTL trading on the RSE.The listing event marked yet another milestone especially this time as the Exchange celebrates its 10 years of operations. ECTL listing is particularly significant as ENERGICOTEL PLC becomes the first company among 12 SMEs under the 1st cohort of the capital market investment clinic project to raise funds and list its securities on the the stock exchange. By the same token, the company also becomes the first company in the energy sector to join the stock market. Presiding over the launch of the listing and trading of ENERGICOTEL PLC’s Corporate Bond, the Minister of Infrastructure Amb. Claver Gatete came back on the role of the Government of Rwanda in the development of the capital market where it uses the market for issuances. “By issuing treasury bonds to the public and privatizing a few of its own companies through the market, the Government has shown a good example to the private sector to follow suit”. The Minister also commended ENERGICOTEL PLC for taking the bold decision to be a pioneer in the energy sector to use capital market in issuing its maiden corporate bond. -

The Challenges of Emerging Stock Markets in Africa, a Case of Rwanda

East African Journal of Science and Technology, Vol.5, Issue 1, 2015 THE CHALLENGES OF EMERGING STOCK MARKETS IN AFRICA, A CASE OF RWANDA STOCK EXCHANGE Wilson KAZARWA The Independent Institute of Lay Adventists of Kigali, Box 6392, Kigali Rwanda E-mail: , Abstract A number of studies previously carried out indicate that capital market development of any economy is synonymous with the growth and economic development, and almost every African country has put an effort to establish a stock market, including Rwanda. This study focuses on the challenges faced by emerging stock markets in Africa, a case study of Rwanda Stock Exchange. The main objectives of this study include establishing the types of securities traded, rules governing the market, challenges facing the market and the suggested recommendations to counter these challenges. A population comprising of five listed companies and the Capital Market Authority were considered and in each case, one respondent was selected using purposive sampling technique. Although this research used more of secondary data that was obtained through literature review, primary data was also collected using an interview guide. The study has found that currently, the types of securities traded include three government bonds and one corporate bond, and stocks from five companies that have listed and cross-listed on the market. The study established that rules are provided and well adhered to and challenges facing the market include among others the general public which is not fully knowledgeable about trading in stocks, coupled with less skilled investment experts and lacking long-term credit, all this reduce profitability and thus limit the chances of listing stocks onto the stock market. -

BRD 2009 Annual Report.Indd

“PROMOTInG GROWTh anD DeVelOPMenT” Rwanda Development Bank Annual Report 2009 Rwanda Development Bank Annual Report 2009 2 2009 Annual Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Profile of BRD 7 Board Of Directors 8 BRD Management 9 Message From The Chairman Of The Board 10 Achievements for the year 13 Corporate Governance 14 INTRODUCTION 18 I OPERATIONS OF THE BANK 22 1.1 Activities of the Bank 22 1.1.1 Loan 22 1.1.2 Equity 23 1.1.3 Guarantee Funds 24 1.2 Portfolio of the Bank 25 1.2.1 Disbursements 27 1.2.2 Loan portfolio per class of risk 28 1.3 Organization of the Bank 30 1.3.1 Organizational structure 30 1.3.2 Human Resources 32 1.3.3 Capacity Building 32 1.4 Risk management of the Bank 34 1.4.1 Risk Management Framework and Responsibilities 34 1.4.2 Achievements of the year 34 1.5 Development Impact 36 II FINANCIAL OVERVIEW OF THE BANK 40 2.1 Financial overview 40 2.2 Report of the Independent Auditors 42 2.3 Financial Statements 45 Shareholders of the Rwandan Development Bank on December 31st 2009 49 Notes To The Financial Statements 50 2009 Annual Report 3 LIST OF tables Table 1: Indicators on the financial soundness of the banking sector on 30/09/2009 19 Table 2: Evolution of outstanding loans in RWF Million (2006 - 2009) 25 Table 3: Trend in disbursements in RWF Million (2006 - 2009)2 27 Table 4: Evolution of the portfolio per class of risk in RWF Million 28 Table 5: Distribution of staff by level of education 32 Table 6: Overview of trainings in 2009 32 4 2009 Annual Report LIST OF GRAPHS Chart 1: Approved Projects by activity 22 Chart 2: Trend -

Topic: Share Price Change and Investment Decision On

COLLEGE OF BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS (CBE) TOPIC: SHARE PRICE CHANGE AND INVESTMENT DECISION ON THE RWANDA STOCK EXCHANGE (2011 – 2016) Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the Degree of Masters of Business Administration specialized in Finance. Submitted by: KANSIIME Gloria Supervisor: Dr. BARAYANDEMA Jonas June, 2018 I DECLARATION I declare that an evaluation of SHARE PRICE CHANGE AND INVESTMENT DECISION ON THE RWANDA STOCK EXCHANGE IN RWANDA is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. KANSIIME Gloria Reg. No: 214003207 MBA-Finance Signature: ……………………………………Date:……../……/2018 I certify that this project entitled “Share price change and investment decision on RSE” was carried out under my supervision. Supervisor name: Dr. BARAYANDEMA Jonas Signature………………………Date:……../………/2018 i COLLEGE OF BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS (CBE) Approval Sheet This thesis entitled SHARE PRICE CHANGE AND INVESTMENT DECISION ON THE RWANDA STOCK EXCHANGE IN RWANDA written and submitted by KANSIIME Gloria In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of finance is hereby accepted and approved. Supervisor Dr. BARAYANDEMA Jonas …………………………………… Date: ……………………… Member of the Jury Member of the Jury Dr. MUSEKURA Celestine Dr. BUSORO R. Theodore …………………………… …………………………… Date: ……………………… Date: ………………… Director of Graduate Studies Dr. NDIKUMANA Philippe ………………………………… Date ………………………… ii DEDICATION First and foremost, I dedicate my work to my beloved Aunt who toiled for my education and sacrificed the descent life they deserved to make sure I attained a bachelor’s degree without which I could not have enrolled for this Master’s Degree program. -

(Smes). These Smes Face Difficulties in Their Establishment and Functioning

FOREWORD The economic development of a country goes through development of its Medium and Small Enterprises (SMEs). These SMEs face difficulties in their establishment and functioning. They come up against different problems but the critical one is lack of information on operational credits be in Rwanda or abroad. Being aware of the importance that the private sector plays in economic development of the country and referring to suggestions made by participants during the official launching ceremony of the first edition, CAPMER has elaborated the second edition of the booklet on sources for financing Small and Medium Enterprises in Rwanda. This booklet deals with different types of financing that SME can access to in Rwanda such as credits from commercial banks, operational guarantee fund, the existing funding programmes in the form of competition of business plans, funds meant for micr finance institutions with purpose of financing the economically poor people who can not access to classical credits, joint ventures, franchising, different types of financing such as leasing, exporting financing, etc. This guide calls mainly upon economic action-oriented agents who figure out becoming entrepreneurs or want to get financing in a bid to implement their ideas of project. It’s meant for micro finance institutions so as to improve conditions of refinancing their activities. Done in Kigali, January 1 st , 2007 Pipien HAKIZABERA Director General 1 TABLE OF CONTENT FOREWORD ....................................................................................................................................... -

Evaluation of Microfinance Services and Potential to Finance Forest Land Restoration (FLR) Investments

Evaluation of Microfinance Services and Potential to Finance Forest Land Restoration (FLR) Investments Final Report Prepared by Azimut Inclusive Finance SPRL November 2016 Azimut Inclusive Finance SPRL TVA : BE 0555.784.066 www.azimut-if.com – [email protected] Evaluation of Microfinance Services and Potential to Finance Forest Land Restoration (FLR) Investments Table of Content EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 1 CONTEXT 4 1.1 BACKGROUND 4 1.2 RATIONALE OF THE STUDY 4 1.3 SPECIFIC OBJECTIVES 4 2 FINANCIAL SECTOR AND REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT 5 2.1 BRIEF OVERVIEW OF THE FINANCIAL SECTOR IN RWANDA 5 2.1.1 FINANCIAL SERVICES PROVIDERS 5 2.2 THE MICROFINANCE SERVICE SECTOR 7 2.2.1 THE CONCEPT OF MICROFINANCE 7 2.2.2 THE MICROFINANCE SERVICE PROVIDERS 7 2.2.3 THE INFORMAL SECTOR 8 2.3 FINANCIAL INCLUSION 10 2.4 RELATED POLICIES AND LAWS 12 2.4.1 POLICY ENVIRONMENT 12 2.4.2 MICROFINANCE POLICY, LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND SUPERVISION 13 3 MICROFINANCE PRODUCTS AND SERVICES AND FLR EFFORTS 15 3.1 EXISTING PRODUCTS AND SERVICES 15 3.1.1 COMMERCIAL BANKS 15 3.1.2 MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS (MFIS) 19 3.2 ADAPTABILITY OF THE MICROFINANCE PRODUCT AND SERVICES TO SUPPORT FLR INITIATIVES (IN GATSIBO AND GICUMBI) 25 3.2.1 OPPORTUNITIES TO SUPPORT FLR INITIATIVES THROUGH MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS 25 3.2.2 CHALLENGES TO SUPPORT FLR INITIATIVES THROUGH MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS 28 3.2.2.1 Challenges related to the microfinance sector 28 3.2.2.2 Other challenges relating to the funding of FLR activities 29 4 RECOMMENDATIONS 30 FINANCIAL TERMS AND DEFINITIONS 35 ANNEXES 36 2 Evaluation of Microfinance Services and Potential to Finance Forest Land Restoration (FLR) Investments Executive Summary Rwanda has made international challenges, notably in terms of credit commitments via the Bonn Challenge to management policies, product restore 2 million hectares of degraded development, weak staff capacities and land. -

World Bank Document

The World Bank RESTRUCTURING ISDS Rwanda Housing Finance Project (P165649) Public Disclosure Authorized Integrated Safeguards Data Sheet Restructuring Stage Public Disclosure Authorized Restructuring Stage | Date ISDS Prepared/Updated: 30-Jun-2020| Report No: ISDSR30028 Public Disclosure Authorized Regional Vice President: Hafez M. H. Ghanem Country Director: Keith H. Hansen Regional Director: Asad Alam Practice Manager/Manager: Niraj Verma Task Team Leader(s): Brice Gakombe, Leyla V. Castillo Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank RESTRUCTURING ISDS Rwanda Housing Finance Project (P165649) Note to Task Teams: The following sections are system generated and can only be edited online in the Portal. I. BASIC INFORMATION 1. BASIC PROJECT DATA Project ID Project Name P165649 Rwanda Housing Finance Project Task Team Leader(s) Country Brice Gakombe, Leyla V. Castillo Rwanda Approval Date Environmental Category 29-Nov-2018 Financial Intermediary Assessment (F) Managing Unit EAEF1 PROJECT FINANCING DATA (US$, Millions) SUMMARY-NewFin1 Total Project Cost 150.00 Total Financing 150.00 Financing Gap 0.00 DETAILS-NewFinEnh1 World Bank Group Financing International Development Association (IDA) 150.00 IDA Credit 150.00 2. PROJECT INFORMATION The World Bank RESTRUCTURING ISDS Rwanda Housing Finance Project (P165649) PROG_INF O Current Program Development Objective To expand access to housing finance to households and to support capital market development in Rwanda. Note to Task Teams: End of system generated content, document is editable from here. 3. PROJECT DESCRIPTION A. Project Status 1. The Rwanda Housing Finance Project (RHFP) is a US$150 million five-year project aiming at expanding access to housing finance to households and to support capital market development in Rwanda. -

The Republic of Rwanda Us$620000000

THE REPUBLIC OF RWANDA U.S.$620,000,000 5.500 per cent. Notes due 2031 Issue Price: 100 per cent. The issue price of the U.S.$620,000,000 5.500 per cent. Notes due 2031 (the “Notes”) of the Republic of Rwanda (“Rwanda”, the “Republic” or the “Issuer”) is 100 per cent. of their principal amount. Unless previously redeemed or purchased and cancelled the Notes will be redeemed at their principal amount on 9 August 2031 (the “Maturity Date”). The Notes will bear interest from 9 August 2021 at the rate of 5.500 per cent. per annum payable semi-annually in arrear on 9 February and 9 August in each year commencing on 9 February 2022. Payments on the Notes will be made in US dollars without deduction for or on account of taxes imposed or levied by the Republic of Rwanda to the extent described under “Terms and Conditions of the Notes–Taxation”. This Offering Circular does not comprise a prospectus for the purposes of Regulation (EU) 2017/1129 as it forms part of domestic law by virtue of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 (“EUWA”) (the “UK Prospectus Regulation”). Application has been made to the United Kingdom Financial Conduct Authority in its capacity as competent authority under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (as amended) (the “FCA”) for the Notes to be admitted to a listing on the Official List of the FCA (the “Official List”) and to the London Stock Exchange plc (the “London Stock Exchange”) for such Notes to be admitted to trading on the London Stock Exchange’s main market (the “Main Market”). -

Learning from Role Models in Rwanda: Incoherent Emulation In

Learning from Role Models in Rwanda: Incoherent emulation in the construction of a Neoliberal Developmental State By Pritish Behuria ABSTRACT In the 21st century, developing country policymakers are offered different market-led role models and varied interpretations of ‘developmental state role models’. Despite this confusion, African countries pursue emulative strategies for different purposes – whether they may be for economic transformation (in line with developmental state strategies), market-led reforms or simply to signal the implementation of ‘best practices’ to please donors. Rwanda has been lauded for the country’s economic recovery since the 1994 genocide, with international financial institutions and heterodox scholars both praising different facets of its development strategy. This paper argues that Rwanda is an example of a country that has simultaneously pursued emulative strategies for different purposes – often even within the same sector. This paper examines the Rwandan government’s emulation of different role models for varied purposes. Two studies of emulation are explored: the emulation of Singapore’s Economic Development Board (RDB) through the establishment of Rwanda’s own Rwanda Development Board (RDB) and the evolution of Rwanda’s financial sector with reference to the use of contending market-led and developmental state models. The paper argues that in Rwanda, incoherent emulation for different purposes has resulted in contradictory tensions within its development strategy and the construction of a neoliberal developmental state. Introduction To catch up with developing countries, governments often choose to emulate the experiences, institutions and strategies of advanced countries. Karl Marx highlighted the opportunities associated with emulating the successes of early developers in reference to Germany’s latecomer status in the context of industrial transformations in England. -

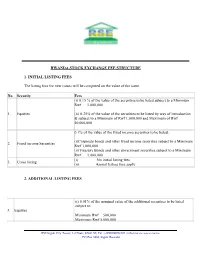

Rwanda Stock Exchange Fee Structure 1. Initial Listing

RWANDA STOCK EXCHANGE FEE STRUCTURE 1. INITIAL LISTING FEES The listing fees for new issues will be computed on the value of the issue. No. Security Fees (i) 0.15 % of the value of the securities to be listed subject to a Minimum Rwf 1,000,000 1. Equities (ii) 0.25% of the value of the securities to be listed by way of introduction & subject to a Minimum of Rwf 1,000,000 and Maximum of Rwf 50,000,000 0.1% of the value of the fixed income securities to be listed: (i)Corporate bonds and other fixed income securities subject to a Minimum 2. Fixed income Securities Rwf 1,000,000 (ii)Treasury Bonds and other government securities subject to a Minimum Rwf 1,000,000 (i) No initial listing fees 3. Cross listing (ii) Annual listing fees apply 2. ADDITIONAL LISTING FEES (i) 0.01% of the nominal value of the additional securities to be listed subject to: 3. Equities Minimum Rwf 500,000 Maximum Rwf 5,000,000 RSE Kigali City Tower, 1st Floor, KN81 ST, Tel : +(250)788516021 ; [email protected] www.rse.rw P O Box 3882, Kigali Rwanda (ii)0.05% of the value of the fixed income securities to be listed: (iii)Corporate bonds and other fixed income securities subject to a Minimum Rwf 1,000,000 4. Fixed income securities (iv) Treasury Bonds and other government securities subject to: Minimum Rwf 1,000,000 Maximum Rwf 10,000,000 The computation of the value of additional listings shall be based on the first date the securities trade ex entitlement after the additional offer. -

“East Asian Miracle” in Africa? : a Case Study Analysis of the Rwandan Governance Reform Process Since 2000

Chasing the “East Asian Miracle” in Africa? : A case study analysis of the Rwandan governance reform process since 2000 Francis Gaudreault A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy degree in Public Administration Faculty of Social Sciences School of Political Studies University of Ottawa © Francis Gaudreault, Ottawa, Canada, 2019 To Amandine My better half, literally ii iii Abstract In the last few decades, many governments around the world—especially in emerging economies—have strayed from neoliberal prescriptions to get closer to a model originating from East Asia: the developmental state. These East Asian countries (Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan) instead of just regulating market mechanisms, have exercised strong control over their economies and society through highly-ambitious long-term economic and social development programs implemented in tight partnership with the private sector. Indeed, this phenomenon is worth exploring when we ask the question of how governance and political economy is evolving in the world and what are the new approaches that can inform governments. This Ph.D. thesis focuses on the evolution of strategies for social and economic development and more specifically on the emergence of developmental states in Africa. By looking at the case of Rwanda that is often considered as a success story in Africa, the aim of this thesis is to show how much this state is transforming its institutions in line with a model that resembles the developmental state, but with its specificities and perspective. Based on a large selection of primary sources gathered in Rwanda between 2015 and 2016, we argue that the system of governance of Rwanda has evolved in a different direction than the typical neo-liberal model often advocated by the West and is following a developmentalist approach much closer to some early East Asian developmental states. -

Corporate Action on Malaria Control: Best Practices and Interventions

CORPORATE ALL ACT CORPORATE i i ANCE ON MALAR ON MALAR ANGOLA BENIN CONGO ETHIOPIA GHANA KENYA LIBERIA MADAGAS - CAR MALAWI MALI MOZAMBIQUE NIGERIA RWANDA SENEGAL SUDAN i TANZANIA UGANDA ZAMBIA ANGOLA BENIN CONGO ETHIOPIA GHANAA CONTROL • i KENYA LIBERIA MADAGASCAR MALAWI MALI MOZAMBIQUE NIGERIA A i RWANDA SENEGAL SUDAN TANZANIA UGANDA ZAMBIA ANGOLA BE N AFR - NIN CONGOCorporate ANGOLA BENIN CONGO Action ETHIOPIA GHANA KENYA LIBERIA i MADAGASCAR MALAWI MALI MOZAMBIQUE NIGERIA RWANDA SENEGAL • (CAMA) CA SUDAN TANZANIAon Malaria UGANDA ZAMBIA Control ANGOLA BENIN CONGO ETHIOPIA AND INTERVENTIONS BEST PRACTICES GHANA KENYABest PracticesLIBERIA MADAGASCAR and Interventions MALAWI MALI MOZAMBIQUE NIGERIA RWANDA SENEGAL SUDAN TANZANIA UGANDA ZAMBIA AN - GOLA BENIN CONGO ANGOLA BENIN CONGO ETHIOPIA GHANA KENYA LIBERIA MADAGASCAR MALAWI MALI MOZAMBIQUE NIGERIA RWANDA REGION: ANGOLA - EAST AFRICA SENEGAL SUDAN TANZANIA UGANDA ZAMBIA ANGOLA BENIN CONGO ETHIOPIA GHANA KENYA LIBERIA MADAGASCAR MALAWI MALI MO - ZAMBIQUE NIGERIA RWANDA SENEGAL SUDAN TANZANIA UGANDA ZAMBIA ANGOLA BENIN CONGO ANGOLA BENINWhat’s CONGO inside: ETHIOPIA GHANA KENYA LIBERIA MADAGASCAR MALAWI •MALI 2011 Case MOZAMBIQUE Studies NI - GERIA RWANDA ANGOLA BENIN CONGO ETHIOPIA• Foreword GHANA KENYA LI - BERIA MADAGASCAR MALAWI MALI MOZAMBIQUE• Critical NIGERIA Success Factors RWANDA SENEGAL SUDAN TANZANIA UGANDA ZAMBIA ANGOLA BENIN CONGO ETHIOPIA GHANA KENYA LIBERIA MADAGASCAR MALAWI MALI MO - ZAMBIQUE NIGERIA RWANDA SENEGAL SUDAN TANZANIA UGANDA ZAMBIA ANGOLA BENIN CONGO ETHIOPIA