The Evolution of Modern Thumri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Syllabus for MA (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental

Syllabus for M.A. (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental (Sitar, Sarod, Guitar, Violin, Santoor) SEMESTER-I Core Course – 1 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Historical and Theoretical Study of Ragas 70 Marks A. Historical Study of the following Ragas from the period of Sangeet Ratnakar onwards to modern times i) Gaul/Gaud iv) Kanhada ii) Bhairav v) Malhar iii) Bilawal vi) Todi B. Development of Raga Classification system in Ancient, Medieval and Modern times. C. Study of the following Ragangas in the modern context:- Sarang, Malhar, Kanhada, Bhairav, Bilawal, Kalyan, Todi. D. Detailed and comparative study of the Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 2 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Music of the Asian Continent 70 Marks A. Study of the Music of the following - China, Arabia, Persia, South East Asia, with special reference to: i) Origin, development and historical background of Music ii) Musical scales iii) Important Musical Instruments B. A comparative study of the music systems mentioned above with Indian Music. Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 3 Practical Credit - 8 Practical : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Stage Performance 70 marks Performance of half an hour’s duration before an audience in Ragas selected from the list of Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Candidate may plan his/her performance in the following manner:- Classical Vocal Music i) Khyal - Bada & chota Khyal with elaborations for Vocal Music. Tarana is optional. Classical Instrumental Music ii) Alap, Jor, Jhala, Masitkhani and Razakhani Gat with eleaborations Semi Classical Music iii) A short piece of classical music /Thumri / Bhajan/ Dhun /a gat in a tala other than teentaal may also be presented. -

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian Rhythm Basics Solkattu, also known as konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally. It comes from the Carnatic music tradition of South India and is mostly used in conjunction with instrumental music and dance instruction, although it has been widely adopted throughout the world as a modern composition and performance tool. Similarly, the music of North India has its own system of rhythm vocalization that is based on Bols, which are the vocalization of specific sounds that correspond to specific sounds that are made on the drums of North India, most notably the Tabla drums. Like in the south, the bols are used in musical training, as well as composition and performance. In addition, solkattu sounds are often referred to as bols, and the practice of reciting bols in the north is sometimes referred to as solkattu, so the distinction between the two practices is blurred a bit. The exercises and compositions we will discuss contain bols that are found in both North and South India, however they come from the tradition of the North Indian tabla drums. Furthermore, the theoretical aspect of the compositions is distinctly from the Hindustani, (north Indian) tradition. Hence, for the purpose of this presentation, the use of the term Solkattu refers to the broader, more general practice of Indian rhythmic language. South Indian Percussion Mridangam Dolak Kanjira Gattam North Indian Percussion Tabla Baya (a.k.a. Tabla) Pakhawaj Indian Rhythm Terms Tal (also tala, taal, or taala) – The Indian system of rhythm. Tal literally means "clap". -

Hindustani Classic Music

HINDUSTANI CLASSIC MUSIC: Junior Grade or Prathamik : Syllabus : No theory exam in this grade Swarajnana Talajnana essential Ragajnana Practicals: 1. Beginning of swarabyasa - in three layas 2. 2 Swaramalikas 5 Lakshnageete Chotakyal Alap - 4 ragas Than - 4 Drupad - should be practiced 3. Bhajan - Vachana - Dasapadas 4. Theental, Dadara, Ektal (Dhruth), Chontal, Juptal, Kheruva Talu - Sam-Pet-Husi-Matras - should practice Tekav. 5. Swarajnana 6. Knowledge of the words - nada, shruthi, Aroha, Avaroha, Vadi - Samvedi, Komal - Theevra - Shuddha - Sasthak - Ganasamay - Thaat - Varjya. 7. Swaralipi - should be learnt. Senior Grade: (Madhyamik) Syllabus : Theory: 1. Paribhashika words 2. Sound & place of emergence of sound 3. The practice of different ragas out of “thaat” - based on Pandith Venkatamukhi Mela System 4. To practice ragalaskhanas of different ragas 5. Different Talas - 9 (Trital, Dadra, Jup, Kherva, Chantal, Tilawad, Roopak, Damar, Deepchandi) explanation of talas with Tekas. 6. Chotakhyal, Badakhyal, Bhajan, Tumari, Geethprakaras - Lakshanas. 7. Life history of Jayadev, Sarangdev, Surdas, Purandaradas, Tansen, Akkamahadevi, Sadarang, Kabeer, Meera, Haridas. 8. Knowledge of musical instrument Practicals: 1. Among 20 ragas - Chotakhyal in each 2. Badakhyal - for 10 ragas (Bhoopali, Yamani, Bheempalas, Bageshree, Malkonnse, Alhaiah Bilawal, Bahar, Kedar, Poorvi, Shankara. 3. Learn to sing one drupad in Tay, Dugun & Changun - one Damargeete. VIDHWAN PROFICIENCY Syllabus: Theory 1. Paribhashika Shabdas. 2. 7 types of Talas - their parts (angas) 3. Tabala bol - Tala Jnana, Vilambitha Ektal, Jumra, Adachontal, Savari, Panjabi, Tappa. 4. Raga lakshanas of Bhairav, Shuddha Sarang, Peelu, Multhani, Sindura, Adanna, Jogiya, Hamsadhwani, Gandamalhara, Ragashree, Darbari, Kannada, Basanthi, Ahirbhairav, Todi etc., Alap, Swaravisthara, Sama Prakruthi, Ragas criticism, Gana samay - should be known. -

The Concept of Tala 1N Semi-Classical Music

The Concept of Tala 1n Semi-Classical Music Peter Manuel Writers on Indian music have generally had less difficulty defining tala than raga, which remains a somewhat abstract, intangible entity. Nevertheless, an examination of the concept of tala in Hindustani semi-classical music reveals that, in many cases, tala itself may be a more elusive and abstract construct than is commonly acknowledged, and, in particular, that just as a raga cannot be adequately characterized by a mere schematic of its ascending and descending scales, similarly, the number of matra-s in a tala may be a secondary or even irrelevant feature in the identification of a tala. The treatment of tala in thumri parallels that of raga in thumn; sharing thumri's characteristic folk affinities, regional variety, stress on sentimental expression rather than theoretical complexity, and a distinctively loose and free approach to theoretical structures. The liberal use of alternate notes and the casual approach to raga distinctions in thumri find parallels in the loose and inconsistent nomenclature of light-classical tala-s and the tendency to identify them not by their theoretical matra-count, but instead by less formal criteria like stress patterns. Just as most thumri raga-s have close affinities with and, in many cases, ongms in the diatonic folk modes of North India, so also the tala-s of thumri (viz ., Deepchandi-in its fourteen- and sixteen-beat varieties-Kaharva, Dadra, and Sitarkhani) appear to have derived from folk meters. Again, like the flexible, free thumri raga-s, the folk meters adopted in semi-classical music acquired some, but not all, of the theoretical and structural characteristics of their classical counterparts. -

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks Semester I 12 300 MUS-PG-T101 Aesthetics Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P102 Analytical Study of Raga-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P103 Analytical Study of Tala-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P104 Raga Studies I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P105 Tala Studies I Practical 4 100 Semester II 16 400 MUS-PG-T201 Folk Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P202 Analytical Study of Raga-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P203 Analytical Study of Tala-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P204 Raga Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P205 Tala Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T206 Music and Media Theory 4 100 Semester III 20 500 MUS-PG-T301 Modern Traditions of Indian Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P302 Analytical Study of Tala-III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Raga Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Tala Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P304 Stage Performance I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T305 Music and Management Theory 4 100 Semester IV 16 400 MUS-PG-T401 Ethnomusicology Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-T402 Dissertation Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P403 Raga Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P404 Tala Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P405 Stage Performance II Practical 4 100 1 Semester I MUS-PG-CT101:- Aesthetic Course Detail- The course will primarily provide an overview of music and allied issues like Aesthetics. The discussions will range from Rasa and its varieties [According to Bharat, Abhinavagupta, and others], thoughts of Rabindranath Tagore and Abanindranath Tagore on music to aesthetics and general comparative. -

WGLT Program Guide, October, 1987

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData WGLT Program Guides Arts and Sciences Fall 10-1-1987 WGLT Program Guide, October, 1987 Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/wgltpg Recommended Citation Illinois State University, "WGLT Program Guide, October, 1987" (1987). WGLT Program Guides. 69. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/wgltpg/69 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts and Sciences at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in WGLT Program Guides by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WGLT fm89 OCTOBER 1987 PROGRAM GUIDE Public Radio from !SU Keith and Betty thought good quality stereo equipment and good quality music made a perfect combination, and so became interested in . underwriting on WGLT. "We felt the WGLT listeners would be very audio BE conscious," Betty said. UNDERWRITER Consequently, the listeners on WGLT are very similar A to the target customers of PROFILE: Curtis Mathes. MEMBER Keith and Betty feel CURTIS public radio is an important Show your support of part of the community and your public radio station MATHES provides a service the SEND and send in your pledge community wants. today! I According to Betty, "Public OF radio brings culture to the YOUR community without the BLOOMINGTON community having to ow that TENDER his month we search for it." summer has feature Curtis The idea of quality radio ended and Mathes of is very similar to Keith and winter is Bloomington Betty's business philosophy. -

12 NI 6340 MASHKOOR ALI KHAN, Vocals ANINDO CHATTERJEE, Tabla KEDAR NAPHADE, Harmonium MICHAEL HARRISON & SHAMPA BHATTACHARYA, Tanpuras

From left to right: Pandit Anindo Chatterjee, Shampa Bhattacharya, Ustad Mashkoor Ali Khan, Michael Harrison, Kedar Naphade Photo credit: Ira Meistrich, edited by Tina Psoinos 12 NI 6340 MASHKOOR ALI KHAN, vocals ANINDO CHATTERJEE, tabla KEDAR NAPHADE, harmonium MICHAEL HARRISON & SHAMPA BHATTACHARYA, tanpuras TRANSCENDENCE Raga Desh: Man Rang Dani, drut bandish in Jhaptal – 9:45 Raga Shahana: Janeman Janeman, madhyalaya bandish in Teental – 14:17 Raga Jhinjhoti: Daata Tumhi Ho, madhyalaya bandish in Rupak tal, Aaj Man Basa Gayee, drut bandish in Teental – 25:01 Raga Bhupali: Deem Dara Dir Dir, tarana in Teental – 4:57 Raga Basant: Geli Geli Andi Andi Dole, drut bandish in Ektal – 9:05 Recorded on 29-30 May, 2015 at Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, NY Produced and Engineered by Adam Abeshouse Edited, Mixed and Mastered by Adam Abeshouse Co-produced by Shampa Bhattacharya, Michael Harrison and Peter Robles Sponsored by the American Academy of Indian Classical Music (AAICM) Photography, Cover Art and Design by Tina Psoinos 2 NI 6340 NI 6340 11 at Carnegie Hall, the Rubin Museum of Art and Raga Music Circle in New York, MITHAS in Boston, A True Master of Khayal; Recollections of a Disciple Raga Samay Festival in Philadelphia and many other venues. His awards are many, but include the Sangeet Natak Akademi Puraskar by the Sangeet Natak Aka- In 1999 I was invited to meet Ustad Mashkoor Ali Khan, or Khan Sahib as we respectfully call him, and to demi, New Delhi, 2015 and the Gandharva Award by the Hindusthan Art & Music Society, Kolkata, accompany him on tanpura at an Indian music festival in New Jersey. -

Sonic Performativity: Analysing Gender in North Indian Classical Vocal Music

The University of Manchester Research Sonic Performativity: Analysing Gender in North Indian Classical Vocal Music DOI: 10.1080/17411912.2015.1082925 Document Version Accepted author manuscript Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Alaghband-Zadeh, C. (2015). Sonic Performativity: Analysing Gender in North Indian Classical Vocal Music. Ethnomusicology Forum, 24(3), 349-379. https://doi.org/10.1080/17411912.2015.1082925 Published in: Ethnomusicology Forum Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:04. Oct. 2021 Sonic performativity: analysing gender in North Indian classical vocal music This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor and Francis in Ethnomusicology Forum (volume 24, issue 3) on 23/10/2015, available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/17411912.2015.1082925 Abstract Many aspects of contemporary North Indian classical vocal music are gendered: genres, improvisational techniques and even certain ornaments evoke gendered connotations for musicians and listeners. -

DEFAULTER PART-A.Xlsx

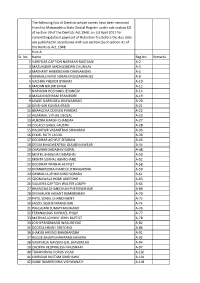

The following lists of Dentists whose names have been removed from the Maharashtra State Dental Register under sub-section (2) of section 39 of the Dentists Act,1948, on 1st April 2017 for committing default payment of Retention fee before the due date are published in accordance with sub section (5) of section 41 of the Dentists Act, 1948. Part-A Sr. No. Name Reg.No. Remarks 1 VARIFDAR CAPTION NARIMAN RUSTAMJI A-2 2 MAZUMDAR MADHUSNDAN CHUNILAL A-3 3 MAEHANT HARIKRISHAN DHANAMDAS A-5 4 GINWALS MINO SORABJI NUSSAWANJEE A-9 5 VACHHA PHEROX BYRAMJI A-10 6 MADAN BALBIR SINGH A-12 7 NARIMAN HOSHANG JEHANGIV A-14 8 MASANI BEHRAM FRAMRORE A-19 9 JAWLE NARENDEA BHAWANRAO A-20 10 DINSHAW KAVINA ERAEH A-21 11 BHARUCHA COOVER PHIRORE A-22 12 AGARWAL VITHAL DEOLAL A-23 13 AURORA HARISH CHANDAR A-27 14 COLACO ISABEL FAUSTIN A-28 15 HALDIPWR VASANTRAO SHAMRAO A-33 16 EEKIEL RUTH JACOB A-39 17 DEODHAR ACHYUT SITARAM A-43 18 DESIAI BHAGWENTRAI GULABSHAWEAR A-44 19 CHAVHAN SADASHIV GOPAL A-48 20 MISTRI JEHANGIR DADABHAI A-50 21 MEHTA SUKHAL ABHECHAND A-52 22 DEODHAR PRABHA ACHYUT A-58 23 DHANBHOORA MANECK JEHANGIRSHA A-59 24 GINWALLA JEHMI MINO SORABJI A-61 25 SOONAWALA HOMI ARDESHIR A-63 26 SIGUEIRA CAPTION WALTER JOSEPH A-65 27 BHANICHA DHANJISHAH PHERIZWSHAW A-66 28 DESHMUKH VASANT RAMKRISHAN A-70 29 PATIL SONAL CHANDHAKNT A-72 30 JAGOS JASSI BYARANSHAW A-74 31 PAHLAJANI SUMATI MUKHAND A-76 32 FERANANDAS RUPHAEL PHILIP A-77 33 MATHIAS JOHNNY JOHN BAPTIST A-78 34 JOSHI PANDMANG WASUDEVAO A-82 35 DCOSTA HENNY SERTORIO A-86 36 JHAKUR ARVIND BHAKHANDRA -

Ruchira Panda, Hindusthani Classical Vocalist and Composer

Ruchira Panda, Hindusthani Classical Vocalist and Composer SUR-TAAL, 1310 Survey Park, Kolkata -700075, India. Contact by : Phone: +91 9883786999 (India), +1 3095177955 (USA) Email Website Facebook - Personal Email: [email protected] Website: ruchirapanda.com Highlights: ❑ “A” grade artist of All India Radio. ❑ Playback-singer - ‘Traditional development of Thumri’ , National TV Channel. India. ❑ Discography : DVD (Live) “Diyaraa Main Waarungi” from Raga Music; CD Saanjh ( Questz World ); also on iTunes, Google Play Music , Amazon Music, Spotify ❑ Performed in almost all of the major Indian Classical Conferences (Tansen, Harivallabh, Dover Lane, Saptak, Gunijan, AACM, LearnQuest etc.) in different countries (India, USA, Canada, UK,Bangladesh, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan) ❑ Empaneled Artist of Hindustani Classical Music : ICCR (Indian Council for Cultural Relations, Government of India), and SPICMACAY ❑ Fellow of The Ministry of Culture, Govt. Of India (2009) ❑ JADUBHATTA AWARD, by Salt Lake Music Festival (2009) ; SANGEET SAMMAN, by Salt Lake Silver Music Festival (2011) ; SANGEET KALARATNA , by Matri Udbodhan Ashram, Patna Synopsis: Ruchira Panda, from Kolkata, India, is the current torch-bearer of the Kotali Gharana, a lineage of classical vocal masters originally hailing from Kotalipara in pre-partition Bengal. She is a solo vocalist and composer who performs across all the major Indian Classical festivals in India, USA, CANADA and Europe. Her signature voice has a deep timbre and high-octane power that also has mind-blowing flexibility to render superfast melodic patterns and intricate emotive glides across microtones. Her repertoire includes Khayal - the grand rendering of an Indian Raga, starting with improvisations at a very slow tempo where each beat cycle can take upwards of a minute, and gradually accelerating to an extremely fast tempo where improvised patterns are rendered at lightning speed . -

Folk/Värld: Asien

Kulturbibliotekets vinylsamling: Folk/Världsmusik: Asien Samlingar F 5092 ISLAM / övrigt Music in the world of Islam. Drums & rhythms F 5090 ISLAM / övrigt Music in the world of Islam. Flutes & trumpets F 5088 ISLAM / övrigt Music in the world of Islam. Lutes F 5091 ISLAM / övrigt Music in the world of Islam. Reeds & bagpipes F 5089 ISLAM / övrigt Music in the world of Islam. Strings F 5087 ISLAM / övrigt Music in the world of Islam. The human voice F 7163 ISLAM / övrigt The holy Koran vol. 1 (Cheik Abdel Bassed Abdel-Samad) F 7164 ISLAM / övrigt The holy Koran vol. 2 (Cheik Abdel Bassed Abdel-Samad) F 7165 ISLAM / övrigt The holy Koran vol. 3 (Cheik Abdel Bassed Abdel-Samad) F 7166 ISLAM / övrigt The holy Koran vol. 4 (Cheik Abdel Bassed Abdel-Samad) F 7167 ISLAM / övrigt The holy Koran vol. 5 (Cheik Abdel Bassed Abdel-Samad) F 7168 ISLAM / övrigt The holy Koran vol. 6 (Cheik Abdel Bassed Abdel-Samad) F 7448 PASSION - SOURCES Div. art. Produced by Peter Gabriel Afghanistan F 3412 AFGHANISTAN (s) Afghanistan. Music from the crossroads of Asia F 1919 AFGHANISTAN (s) Folkmusik från Afghanistan och Iran F 3414 AFGHANISTAN (s) Music of Afghanistan F 4100 AFGHANISTAN (s) Musiques classiques & populaires F 1919 IRAK (s) Folkmusik från Afghanistan och Iran Azerbaijan F 5231 AZERBAIJAN (s) The music of Azerbaijan Bahrein F 1893 ASIEN (s) Folkmusik från Persiska viken ( Oman, Bahrein, Sharjak ) 2020-07-28 sida 1 Kulturbibliotekets vinylsamling: Folk/Världsmusik: Asien Bali F 3051 BALI (s) Baliness theatre and dance music F 7516 BALI (s) Barong. -

Gharana: the True Meaning - Gundecha Brothers

Gharana: The true meaning - Gundecha Brothers Our probe of the term ‘Gharana’ may be incomplete if we dwell only on the literal meaning of the term. Hence the in-depth examination is a must. It should be kept in mind that, musical ‘Gharana’ (or tradition, in a general sense) is born out of the genius of a master and his creative abilities. Even then, gharana imbibes the traits of some auxiliaries; which are not necessarily a gharana of their own. It can easily be seen to be a current of musical thoughts and the perpetuation of the tradition. Thus said, we should never attempt to fit an immobile frame. The only address of such a current will be a stream of creative thoughts. But, it has been a wrong practice to recognise and preach the term gharana as a fixed entity. The gharana itself is a product of such a stream. Also, it will be an injustice to perceive the stream of music with a fixed set of concepts. A contemplated study of a musical gharana will reveal us that it were the product of a master; his creative thoughts, his perceptions, his aesthetic thinking, his nature and even his limitations. After the master, his gharana propitiates such type of music only. A good study also tells about a gharana’s specialities like: the voice culture, tempi of singing, perception of ragas, compositions, the improvisation of text as well as rhythm etc. All such faculties compile and give rise to a gharana which has a flavour of its own. Amongst all, the voice culture maintains the highest importance in any gharana.