A Review of Techniques for Marking Snakes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uromacer Catesbyi (Schlegel) 1. Uromacer Catesbyi Catesbyi Schlegel 2. Uromacer Catesbyi Cereolineatus Schwartz 3. Uromacer Cate

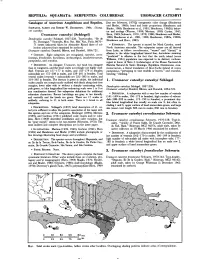

T 356.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE UROMACER CATESBYI Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. [but see Schwartz,' 1970]); ontogenetic color change (Henderson and Binder, 1980); head and body proportions (Henderson and SCHWARTZ,ALBERTANDROBERTW. HENDERSON.1984. Uroma• Binder, 1980; Henderson et a\., 1981; Henderson, 1982b); behav• cer catesbyi. ior and ecology (Werner, 1909; Mertens, 1939; Curtiss, 1947; Uromacer catesbyi (Schlegel) Horn, 1969; Schwartz, 1970, 1979, 1980; Henderson and Binder, 1980; Henderson et a\., 1981, 1982; Henderson, 1982a, 1982b; Dendrophis catesbyi Schlegel, 1837:226. Type-locality, "lie de Henderson and Horn, 1983). St.- Domingue." Syntypes, Mus. Nat. Hist. Nat., Paris, 8670• 71 (sexes unknown) taken by Alexandre Ricord (date of col• • ETYMOLOGY.The species is named for Mark Catesby, noted lection unknown) (not examined by authors). North American naturalist. The subspecies names are all derived Uromacer catesbyi: Dumeril, Bibron, and Dumeril, 1854:72l. from Latin, as follow: cereolineatus, "waxen" and "thread," in allusion to the white longitudinal lateral line; hariolatus meaning • CONTENT.Eight subspecies are recognized, catesbyi, cereo• "predicted" in allusion to the fact that the north island (sensu lineatus,frondicolor, hariolatus, inchausteguii, insulaevaccarum, Williams, 1961) population was expected to be distinct; inchaus• pampineus, and scandax. teguii in honor of Sixto J. Inchaustegui, of the Museo Nacional de • DEFINITION.An elongate Uromacer, but head less elongate Historia Natural de Santo Domingo, Republica Dominicana; insu• than in congeners, and the head scales accordingly not highly mod• laevaccarum, a literal translation of lIe-a-Vache (island of cows), ified. Ventrals are 157-177 in males, and 155-179 in females; pampineus, "pertaining to vine tendrils or leaves;" and scandax, subcaudals are 172-208 in males, and 159-201 in females. -

A Very European Tale – Britain Still Has Only Three Snake Species, but Its Grass Snake Is Now Assigned to Another Species (Natrix Helvetica)

SHORT COMMUNICATION The Herpetological Bulletin 141, 2017: 44-45 A very European tale – Britain still has only three snake species, but its grass snake is now assigned to another species (Natrix helvetica) UWE FRITZ1* & CAROLIN KINDLER1 1Senckenberg Natural History Collections Dresden, Museum of Zoology, A. B. Meyer Building, 01109 Dresden, Germany *Corresponding author Email: [email protected] ollowing several investigations of the phylogeography and systematics of grass snakes (Fritz et al., 2012; FKindler et al., 2013, 2014; Pokrant et al., 2016), we published a further detailed study on this topic in August (Kindler et al., 2017). Our new investigation revealed that only very limited gene flow occurs between western barred grass snakes and eastern common grass snakes. Consequently, we concluded that the barred grass snake (Fig. 1), previously a subspecies, should be elevated to a full species. August being the ‘silly season’ for news stories led the local media, including the highly respected BBC, to claim that Britain has now an additional snake species, i.e. four instead of three species – the northern viper (Vipera Figure 1. Young N. helvetica showing the distinctive lateral bars berus), the smooth snake (Coronella austriaca) as well as from which the species common name the ‘barred grass snake’ is derived (photo: © Jason Steel) two species of grass snake, the common grass snake (Natrix natrix) and the newly recognised barred grass snake (Natrix helvetica). findings. However, some southern populations identified This upheaval resulted from a complete misunderstanding by Thorpe with barred grass snakes, for instance from of a press release by the Senckenberg Institution. The press northern Italy, turned out to be distinct from N. -

Other Contributions

Other Contributions NATURE NOTES Amphibia: Caudata Ambystoma ordinarium. Predation by a Black-necked Gartersnake (Thamnophis cyrtopsis). The Michoacán Stream Salamander (Ambystoma ordinarium) is a facultatively paedomorphic ambystomatid species. Paedomorphic adults and larvae are found in montane streams, while metamorphic adults are terrestrial, remaining near natal streams (Ruiz-Martínez et al., 2014). Streams inhabited by this species are immersed in pine, pine-oak, and fir for- ests in the central part of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt (Luna-Vega et al., 2007). All known localities where A. ordinarium has been recorded are situated between the vicinity of Lake Patzcuaro in the north-central portion of the state of Michoacan and Tianguistenco in the western part of the state of México (Ruiz-Martínez et al., 2014). This species is considered Endangered by the IUCN (IUCN, 2015), is protected by the government of Mexico, under the category Pr (special protection) (AmphibiaWeb; accessed 1April 2016), and Wilson et al. (2013) scored it at the upper end of the medium vulnerability level. Data available on the life history and biology of A. ordinarium is restricted to the species description (Taylor, 1940), distribution (Shaffer, 1984; Anderson and Worthington, 1971), diet composition (Alvarado-Díaz et al., 2002), phylogeny (Weisrock et al., 2006) and the effect of habitat quality on diet diversity (Ruiz-Martínez et al., 2014). We did not find predation records on this species in the literature, and in this note we present information on a predation attack on an adult neotenic A. ordinarium by a Thamnophis cyrtopsis. On 13 July 2010 at 1300 h, while conducting an ecological study of A. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/06/2021 09:29:00AM Via Free Access 42 Luiselli Et Al

Contributions to Zoology, 74 (1/2) 41-49 (2005) Analysis of a herpetofaunal community from an altered marshy area in Sicily; with special remarks on habitat use (niche breadth and overlap), relative abundance of lizards and snakes, and the correlation between predator abundance and tail loss in lizards Luca Luiselli1, Francesco M. Angelici2, Massimiliano Di Vittorio3, Antonio Spinnato3, Edoardo Politano4 1 F.I.Z.V. (Ecology), via Olona 7, I-00198 Rome, Italy. E-mail: [email protected] 2 F.I.Z.V. (Mammalogy), via Cleonia 30, I-00152 Rome, Italy. 3 Via Jevolella 2, Termini Imprese (PA), Italy. 4 Centre of Environmental Studies ‘Demetra’, via Tomassoni 17, I-61032 Fano (PU), Italy Abstract relationships, thus rendering the examination of the relationships between predators and prey an extreme- A field survey was conducted in a highly degraded barren en- ly complicated task for the ecologist (e.g., see Con- vironment in Sicily in order to investigate herpetofaunal com- nell, 1975; May, 1976; Schoener, 1986). However, munity composition and structure, habitat use (niche breadth and there is considerable literature (both theoretical and overlap) and relative abundance of a snake predator and two spe- empirical) indicating that case studies of extremely cies of lizard prey. The site was chosen because it has a simple community structure and thus there is potentially less ecological simple communities, together with the use of appropri- complexity to cloud any patterns observed. We found an unexpect- ate minimal models, can help us to understand the edly high overlap in habitat use between the two closely related basis of complex patterns of ecological relationships lizards that might be explained either by a high competition for among species (Thom, 1975; Arditi and Ginzburg, space or through predator-mediated co-existence i.e. -

Population and Ecological Characteristics of the Dice Snake, Natrix Tessellata

Turkish Journal of Zoology Turk J Zool (2019) 43: 657-664 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/zoology/ © TÜBİTAK Short Communication doi:10.3906/zoo-1811-8 Population and ecological characteristics of the dice snake, Natrix tessellata (Laurenti, 1768), in lower portions of the Vrbanja River (Republic of Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina) 1, 2 1 2 Goran ŠUKALO *, Sonja NIKOLIĆ , Dejan DMITROVIĆ , Ljiljana TOMOVIĆ 1 Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, University of Banja Luka, Banja Luka, Republic of Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina 2 Institute of Zoology, Faculty of Biology, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia Received: 06.11.2018 Accepted/Published Online: 12.09.2019 Final Version: 01.11.2019 Abstract: Despite their comparative richness and accessibility in the Republic of Srpska and in Bosnia and Herzegovina in general, population studies of reptiles have not been performed in Srpska until recently. For example, one of the most common snake species in this area is the dice snake; nevertheless, previous studies have only reported its distribution. The aim of the present study was to analyze characteristics of the dice snake population along the Vrbanja River. Animals were processed during 2011 throughout their activity period. In total, 199 individuals of all ages were collected. We observed substantial differences in numbers of animals captured in different habitat types classified according to the level of anthropogenic influence. Unexpectedly, the largest number of snakes was captured in the zone with the highest anthropogenic influence, while the smallest number was observed in the zone with no anthropogenic pressures. The above is probably connected with the observed greater number of their most common prey, as well as the absence of raptors in areas with human impact. -

Zootaxa, Molecular Phylogeny, Classification, and Biogeography Of

Zootaxa 2067: 1–28 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Molecular phylogeny, classification, and biogeography of West Indian racer snakes of the Tribe Alsophiini (Squamata, Dipsadidae, Xenodontinae) S. BLAIR HEDGES1, ARNAUD COULOUX2, & NICOLAS VIDAL3,4 1Department of Biology, 208 Mueller Lab, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802-5301 USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Genoscope. Centre National de Séquençage, 2 rue Gaston Crémieux, CP5706, 91057 Evry Cedex, France www.genoscope.fr 3UMR 7138, Département Systématique et Evolution, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, CP 26, 57 rue Cuvier, 75005 Paris, France 4Corresponding author. E-mail : [email protected] Abstract Most West Indian snakes of the family Dipsadidae belong to the Subfamily Xenodontinae and Tribe Alsophiini. As recognized here, alsophiine snakes are exclusively West Indian and comprise 43 species distributed throughout the region. These snakes are slender and typically fast-moving (active foraging), diurnal species often called racers. For the last four decades, their classification into six genera was based on a study utilizing hemipenial and external morphology and which concluded that their biogeographic history involved multiple colonizations from the mainland. Although subsequent studies have mostly disagreed with that phylogeny and taxonomy, no major changes in the classification have been proposed until now. Here we present a DNA sequence analysis of five mitochondrial genes and one nuclear gene in 35 species and subspecies of alsophiines. Our results are more consistent with geography than previous classifications based on morphology, and support a reclassification of the species of alsophiines into seven named and three new genera: Alsophis Fitzinger (Lesser Antilles), Arrhyton Günther (Cuba), Borikenophis Hedges & Vidal gen. -

Download Download

Phyllomedusa 20(1):89–92, 2021 © 2021 Universidade de São Paulo - ESALQ ISSN 1519-1397 (print) / ISSN 2316-9079 (online) doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9079.v20i1p89-92 Short CommuniCation Dietary records for Oxybelis rutherfordi (Serpentes: Colubridae) from Trinidad and Tobago Renoir J. Auguste,1 Jason-Marc Mohamed,2 Marie-Elise Maingot,1 and Kyle Edghill3 1 Department of Life Sciences, The University of the West Indies. St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago. E-mail: renguste@ gmail.com. 2 Palmiste, Trinidad, Trinidad and Tobago. 3 D’Abadie, Trinidad, Trinidad and Tobago. Keywords: diet, island ecology, lizards, predator-prey relationship, Rutherford’s vine snake. Palavras-chave: dieta, ecologia de ilhas, relação predador-presa, serpente-arborícola-de-rutherford. SnaKes feed on a variety of prey (Greene islands of Trinidad and Tobago (Jadin et al. 1983). The diet of the Brown Vine SnaKe, 2020). Jadin et al. (2019) recognized that O. Oxybelis aeneus (Wagler, 1824), is well Known; rutherfordi is distinct from O. aeneus and lizards are the most common prey. This species described the species (Jadinet al. 2020). Because has no apparent taxonomic proclivity in its previous natural history information for O. dietary choices, which suggests that their rutherfordi was combined with O. aeneus selection of lizards is random (Mesquita et al. (Murphy et al. 2018), it is appropriate to provide 2012, Sousa et al. 2020). However, reports on new information for O. rutherfordi. the diet of Rutherford’s Vine Snake, Oxybelis Three separate predation events by O. rutherfordi Jadin, Blair, OrlofsKe, Jowers, rutherfordi were observed in January and Rivas, Vitt, Ray, Smith, and Murphy, 2020, are February 2021 involving three lizard species on limited (Murphy et al. -

Predation Attempt by Oxybelis Aeneus(Wagler)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Firenze University Press: E-Journals Acta Herpetologica 5(1): 19-22, 2010 Predation attempt by Oxybelis aeneus (Wagler) (Mexican Vine- snake) on Basiliscus plumifrons (Cope) Paul B.C. Grant1, Todd R. Lewis 2 1 4901 Cherry Tree Bend, Victoria B. C., V8Y 1SI, Canada. 2 Westfield, 4 Worgret Road, Wareham, Dorset, BH20 4PJ, UK. Corresponding author. E-mail: ecolewis@ gmail.com Submitted on: 2009, 31st August; revised on: 2010, 3rd March; accepted on: on2010, 13th March. Oxybelis aeneus is a broadly distributed vine snake of the New World (Keiser, 1982; Savage, 2002). Its enormous range stretches from Arizona and southern Texas, through Mexico, Honduras, Belize, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, and into South America where it is found in Colombia, Ecuador, north-western Peru on the Pacific ver- sant, and as far south as Brazil and Bolivia on the Atlantic versant (Keiser, 1974, 1982; Dixon and Soini, 1986; Keiser, 1991; Pérez-Santos and Moreno, 1991; Lehr et al., 2002; Savage, 2002; Hernandez, 2004; Uetz, 2006; Cisneros-Heredia and Touzet, 2007; AGFD, 2008). It is also found on Trinidad and Tobago and other islands such as offshore atolls around Belize (Campbell, 1998; Platt et al., 2002). O. aeneus is easily recognised from other Oxybelis sp. vine snakes by its light-grey dorsum and black mouth lining. It is a common colubrid snake within its range, inhabit- ing open areas, grassland with scrub, forest edges, clearings within forest, abandoned pas- tures, riparian premontane wet forest, premontane rain forest, in addition to lowland wet and dry forest (Franzen, 1996; Savage, 2002). -

A New Vine Snake (Reptilia, Colubridae, Oxybelis) from Peru and Redescription of O

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2021 A new vine snake (Reptilia, Colubridae, Oxybelis) from Peru and redescription of O. acuminatus Robert C. Jadin University of Wisconsin - Eau Claire Michael J. Jowers Universidade do Porto Sarah A. Orlofske University of Wisconsin - Eau Claire William E. Duellman University of Kansas Christopher Blair CUNY New York City College of Technology See next page for additional authors How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/685 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Authors Robert C. Jadin, Michael J. Jowers, Sarah A. Orlofske, William E. Duellman, Christopher Blair, and John C. Murphy This article is available at CUNY Academic Works: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/685 Evolutionary Systematics. 5 2021, 1–12 | DOI 10.3897/evolsyst.5.60626 A new vine snake (Reptilia, Colubridae, Oxybelis) from Peru and redescription of O. acuminatus Robert C. Jadin1, Michael J. Jowers2, Sarah A. Orlofske1, William E. Duellman3, Christopher Blair4,5, John C. Murphy6,7 1 Department of Biology and Museum of Natural History, University of Wisconsin Stevens Point, Stevens Point, WI 54481, USA 2 CIBIO/InBIO (Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos), Universidade do Porto, Campus Agrario De Vairão, 4485- 661, Vairão, Portugal 3 Biodiversity Institute, University of Kansas, 1345 Jayhawk Blvd., Lawrence, Kansas 66045-7593, USA 4 Department of Biological Sciences, New York City College of Technology, The City University of New York, 285 Jay Street, Brooklyn, NY 112015, USA 5 Biology PhD Program, CUNY Graduate Center, 365 5th Ave., New York, NY 10016, USA 6 Science and Education, Field Museum of Natural History, 1400 S. -

Ecological Functions of Neotropical Amphibians and Reptiles: a Review

Univ. Sci. 2015, Vol. 20 (2): 229-245 doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.SC20-2.efna Freely available on line REVIEW ARTICLE Ecological functions of neotropical amphibians and reptiles: a review Cortés-Gomez AM1, Ruiz-Agudelo CA2 , Valencia-Aguilar A3, Ladle RJ4 Abstract Amphibians and reptiles (herps) are the most abundant and diverse vertebrate taxa in tropical ecosystems. Nevertheless, little is known about their role in maintaining and regulating ecosystem functions and, by extension, their potential value for supporting ecosystem services. Here, we review research on the ecological functions of Neotropical herps, in different sources (the bibliographic databases, book chapters, etc.). A total of 167 Neotropical herpetology studies published over the last four decades (1970 to 2014) were reviewed, providing information on more than 100 species that contribute to at least five categories of ecological functions: i) nutrient cycling; ii) bioturbation; iii) pollination; iv) seed dispersal, and; v) energy flow through ecosystems. We emphasize the need to expand the knowledge about ecological functions in Neotropical ecosystems and the mechanisms behind these, through the study of functional traits and analysis of ecological processes. Many of these functions provide key ecosystem services, such as biological pest control, seed dispersal and water quality. By knowing and understanding the functions that perform the herps in ecosystems, management plans for cultural landscapes, restoration or recovery projects of landscapes that involve aquatic and terrestrial systems, development of comprehensive plans and detailed conservation of species and ecosystems may be structured in a more appropriate way. Besides information gaps identified in this review, this contribution explores these issues in terms of better understanding of key questions in the study of ecosystem services and biodiversity and, also, of how these services are generated. -

Reptiles and Amphibians of Lamanai Outpost Lodge, Belize

Reptiles and Amphibians of the Lamanai Outpost Lodge, Orange Walk District, Belize Ryan L. Lynch, Mike Rochford, Laura A. Brandt and Frank J. Mazzotti University of Florida, Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center; 3205 College Avenue; Fort Lauderdale, Florida 33314 All pictures taken by RLL: [email protected] and MR: [email protected] Vaillant’s Frog Rio Grande Leopard Frog Common Mexican Treefrog Rana vaillanti Rana berlandieri Smilisca baudinii Veined Treefrog Red Eyed Treefrog Stauffer’s Treefrog Phrynohyas venulosa Agalychnis callidryas Scinax staufferi White-lipped Frog Fringe-toed Foam Frog Fringe-toed Foam Frog Leptodactylus labialis Leptodactylus melanonotus Leptodactylus melanonotus 1 Reptiles and Amphibians of the Lamanai Outpost Lodge, Orange Walk District, Belize Ryan L. Lynch, Mike Rochford, Laura A. Brandt and Frank J. Mazzotti University of Florida, Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center; 3205 College Avenue; Fort Lauderdale, Florida 33314 All pictures taken by RLL: [email protected] and MR: [email protected] Tungara Frog Marine Toad Gulf Coast Toad Physalaemus pustulosus Bufo marinus Bufo valliceps Sheep Toad House Gecko Dwarf Bark Gecko Hypopachus variolosus Hemidactylus frenatus Shaerodactylus millepunctatus Turnip-tailed Gecko Yucatan Banded Gecko Yucatan Banded Gecko Thecadactylus rapicaudus Coleonyx elegans Coleonyx elegans 2 Reptiles and Amphibians of the Lamanai Outpost Lodge, Orange Walk District, Belize Ryan L. Lynch, Mike Rochford, Laura A. Brandt and Frank J. Mazzotti University -

Hiding in the Lianas of the Tree of Life Molecular Phylogenetics And

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 134 (2019) 61–65 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Short Communication Hiding in the lianas of the tree of life: Molecular phylogenetics and species T delimitation reveal considerable cryptic diversity of New World Vine Snakes ⁎ Robert C. Jadina, , Christopher Blairb,c, Michael J. Jowersd, Anthony Carmonaa, John C. Murphye,1 a Department of Biology, Northeastern Illinois University, 5500 North St., Louis Avenue, Chicago, IL 60625-4699, USA b Department of Biological Sciences, New York City College of Technology, The City University of New York, 285 Jay Street, Brooklyn, NY 1120, USA c Biology PhD Program, CUNY Graduate Center, 365 5th Ave., New York, NY 10016, USA d CIBIO/InBIO (Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos), Universidade do Porto, Campus Agrario De Vairão, 4485-661 Vairão, Portugal e Science and Education, Field Museum of Natural History, 1400 S. Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL 60605, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The Brown Vine Snake, Oxybelis aeneus, is considered a single species despite the fact its distribution covers an Bayesian estimated 10% of the Earth’s land surface, inhabiting a variety of ecosystems throughout North, Central, and Biodiversity South America and is distributed across numerous biogeographic barriers. Here we assemble a multilocus mo- Oxybelis lecular dataset (i.e. cyt b, ND4, cmos, PRLR) derived from Middle American populations to examine for the first RASP time the evolutionary history of Oxybelis and test for evidence of cryptic lineages using Bayesian and maximum Reptilia likelihood criteria. Our divergence time estimates suggest that Oxybelis diverged from its sister genus, Leptophis, Serpentes approximately 20.5 million years ago (Ma) during the lower-Miocene.