Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Research Tasks You Do Most: Here's How at Lexis

The research Search Search with “terms & connectors” tasks you do most: Search a specific source Here’s how at Combine sources/search favorite sources Lexis Advance® Search with segments and commands Find in one step Many of your favorite research tasks— Retrieve full-text documents by citation those tasks you rely on to get you to information you need—can be completed Get and print by citation at Lexis Advance® in a couple of steps. Find a full-text case by name Try them out. Get comfortable. They’re so simple you’ll memorize them quickly. Request a Shepard’s® report Need more assistance with Lexis Advance? Browse by hierarchy Go to Lexis Advance Support site at lexisnexis.com/advancesupport for help. Browse or search a table of contents (TOC) Call LexisNexis® Customer Support at 800-543-6862. Browse statutes Talk to a representative virtually 24/7. Research legal topics Research a specific legal topic (Browse Topics) Use LexisNexis® headnotes to find documents Using/delivering results Refine your search results Copy cites and text for your work Print, email, download and save to Folders Search Search with “terms & connectors” Combine sources/search favorite sources To combine sources: 1. Enter a partial source name in the red search box. The word wheel will make suggestions. Select a source. 2. Repeat to add more sources to your search. The source combination is saved automatically in Recent & Favorites. Just enter your words and connectors in the red search box, e.g., same sex! W/10 marriage, and select Search. Lexis Advance View recent searches and create Favorites: automatically interprets search commands such as ! and * • Select the Filters pull-down menu in the red search box to truncate words and W/n, OR, AND, &, etc. -

ISSUE 4 ® the Newsletter Designed for Nexis.Com Power Users FOURTH QUARTER

LexisNexis® Corporate Information Professional Update ISSUE 4 ® The newsletter designed for nexis.com power users FOURTH QUARTER What’s new at nexis.com®, plus searching strategies to help “power users” solve the information issues their businesses face. Full-text features: New biographical group sources on executives trim The new current-awareness tool developed your research time and compile results specifically for small to midsize organizations … LexisNexis now offers four new group sources at nexis.com® and lexis.com® LexisNexis® Publisher … 12:62 that provide detailed biographical information on company executives, New biographical group sources on executives employees and government leaders. trim your research time and compile results … 12:65 One search covers 20+ executive biographical sources The Executive Directories provides biographical information on directors and executives of major corporations in the United States and Europe. Search by executive name, company, city/state or a variety of other sections. Find summaries and/or links to full-text PDFs of: Review the sources available through The Executive Directories. One million phone numbers added to Search results are presented in standard nexis.com group source format, LexisNexis® Public Records sources … 12:56 with a left navigation pane that allows you to focus in on specific publications within the results. Trademark prosecution history now included with registration documents … 12:56 Get people news plus biographical stories in one source Biographies Plus News adds people-related news sources and selected ® LexisNexis Company Dossier: Search by biographical stories, obituaries and business-related stories covering ® radius or Fortune designation … 12:56 company executives from the News, All (English, Full Text) source. -

RELX Group Annual Reports and Financial Statements 2015

Annual Reports and Financial Statements 2015 Annual Reports and Financial Statements 2015 RELX Group is a world-leading provider of information and analytics for professional and business customers across industries. We help scientists make new discoveries, lawyers win cases, doctors save lives and insurance companies offer customers lower prices. We save taxpayers and consumers money by preventing fraud and help executives forge commercial relationships with their clients. In short, we enable our customers to make better decisions, get better results and be more productive. RELX PLC is a London listed holding company which owns 52.9 percent of RELX Group. RELX NV is an Amsterdam listed holding company which owns 47.1 percent of RELX Group. Forward-looking statements The Reports and Financial Statements 2015 contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of Section 27A of the US Securities Act of 1933, as amended, and Section 21E of the US Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended. These statements are subject to a number of risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results or outcomes to differ materially from those currently being anticipated. The terms “estimate”, “project”, “plan”, “intend”, “expect”, “should be”, “will be”, “believe”, “trends” and similar expressions identify forward-looking statements. Factors which may cause future outcomes to differ from those foreseen in forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to competitive factors in the industries in which the Group operates; demand for the Group’s products and services; exchange rate fluctuations; general economic and business conditions; legislative, fiscal, tax and regulatory developments and political risks; the availability of third-party content and data; breaches of our data security systems and interruptions in our information technology systems; changes in law and legal interpretations affecting the Group’s intellectual property rights and other risks referenced from time to time in the filings of the Group with the US Securities and Exchange Commission. -

School of Library and Information Science Central University of Gujarat

School of Library and Information Science Central University of Gujarat Master of Library and Information Science COURSE AND CREDIT STRUCTURE Semester Course Course Title Credits Code 1 LIS-401 Knowledge Society 4 LIS-402 Knowledge Organization I: Classification (Theory & Practice) 3 LIS-403 Knowledge Processing I: Cataloguing (Theory & Practice) 3 LIS-404 Information Sources and Services 4 LIS-405 Information Communication Technology (Theory & Practice) 4 2 LIS-451 Management of Libraries and Information Centres 4 LIS-452 Information Storage and Retrieval 4 LIS-453 Knowledge Organization II: Classification (Theory & Practice) 3 LIS-454 Knowledge Processing II: Cataloguing (Theory & Practice) 3 LIS-455 Library Automation (Theory and Practice) 4 3 LIS-501 Research Methodology 4 LIS-502 Digital Libraries (Theory) 3 LIS-503 Web Technologies and Web-based Information Management 3 (Theory and Practice) LIS-541 Digital Libraries (Practice) 3 LIS-542 Library Internship in a Recognized Library/Information 5 Centre 4 LIS-551 Knowledge Management 4 LIS-552 Informetrics and Scientometrics 3 LIS-571* Social Science Information Systems 3 LIS-572* Community Information Systems LIS-573* Science Information Systems LIS-574* Agricultural Information Systems LIS-575* Health Information Systems LIS-591 Dissertation 8 Total credits 72 *Students are required to select any one course from LIS-571 to LIS-575 1 SEMESTER I Name of the Programme Master of Library and Information Science Course Title Knowledge Society Course Number LIS-401 Semester 1 Credits 4 Objectives of the Course: To introduce the basic concepts of knowledge and its formation To understand the influence of knowledge in the society To understand the process of communication Course Content: Evolution of Knowledge Society, Components, Dimensions, and Indicators of Knowledge Society. -

Computer Support for Collaborative Learning (CSCL)

© COMUNICAR, 42; XXI MEDIA EDUCATION RESEARCH JOURNAL ISSN: 1134-3478 / DL: H-189-93 / e-ISSN: 1988-3293 Andalusia (Spain), n. 42; vol. XXI 1st semester, 01 January 2014 INDEXED INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH JOURNAL INTERNATIONAL DATABASES LIBRARY CATALOGUES • JOURNAL CITATION REPORTS (JCR) (Thomson Reuters)® • WORLDCAT • SOCIAL SCIENCES CITATION INDEX / SOCIAL SCISEARCH (Thomson Reuters) • REBIUN/CRUE • SCOPUS® • SUMARIS (CBUC) • ERIH (European Science Foundation) • NEW-JOUR • FRANCIS (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique de Francia) • ELEKTRONISCHE ZEITSCHRIFTENBIBLIOTHEK (Electronic Journals Library) • SOCIOLOGICAL ABSTRACTS (ProQuest-CSA) • THE COLORADO ALLIANCE OF RESEARCH LIBRARIES • COMMUNICATION & MASS MEDIA COMPLETE • INTUTE (University of Manchester) • ERA (Educational Research Abstract) • ELECTRONICS RESOURCES HKU LIBRARIES (Hong Kong University, HKU) • IBZ (Internat. Bibliography of Periodical Literature in the Social Sciences) • BIBLIOTECA DIGITAL (University of Belgrano) • IBR (International Bibliography of Book Reviews in the Social Sciences) BIBLIOGRAPHICAL DATABASES • SOCIAL SERVICES ABSTRACTS • DIALNET (Alertas de Literatura Científica Hispana) • ACADEMIC SEARCH COMPLETE (EBSCO) • PSICODOC • MLA (Modern International Bibliography) • REDINED (Ministerio de Educación de Spain) • COMMUNICATION ABSTRACTS (EBSCO) • CEDAL (Instituto Latinoamericano de Comunicación Educativa: ILCE) • EDUCATION INDEX/Abstracts, OmniFile Full Text Megs/Select (Wilson) • OEI (Centro de Recursos de la Organización de Estados Iberoamericanos) • -

Reed Elsevier Study 17/6/10 11:09 Page 1

Reed Elsevier Study 17/6/10 11:09 Page 1 www.thetimes100.co.uk Corporate Responsibility and stakeholders Curriculum Topics • Internal stakeholders • External stakeholders • Stakeholder conflict • Benefits of stakeholder focus Introduction The company now operates in more than 200 locations worldwide and annual revenues for 2009 were £6 billion. Revenues are Reed Elsevier is a leading provider of professional research largely from subscriptions to its titles. It employs around 32,000 information to organisations around the world. It publishes people including IT specialists, editorial teams and marketing, journals, books and databases and manages exhibitions and sales and customer service staff. To enable the business to focus events. Its well-known titles - such as New Scientist and The on specific customer needs, the company has four divisions. Lancet - appear both in print and online. Reed Elsevier has a worldwide customer base working in many fields, including 1. Elsevier – publishing science and health information to promote science, research and the law, as well as in public and academic research and discovery ® libraries and commercial organisations. This includes around 2. LexisNexis – A leading global provider of content-enabled 11 million scientists who access information direct from workflow solutions designed specifically for professionals in the Reed Elsevier’s ScienceDirect database – the world’s largest legal, risk management, corporate, government, law online library of full-text research papers. enforcement, accounting, and academic markets. Across the globe, LexisNexis provides customers with access to billions of Reed Elsevier was formed in 1993 when the businesses of the searchable documents and records from more than 45,000 British publisher Reed International and the Dutch publisher legal, news and business sources. -

Research Library Page 1

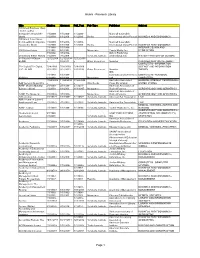

Alumni - Research Library Title Citation Abstract Full_Text Pub Type Publisher Subject 100 Great Business Ideas : from Leading Companies Around the 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- Marshall Cavendish World 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 Books International (Asia) Pte Ltd BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS 100 Great Sales Ideas : from Leading Companies 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- Marshall Cavendish Around the World 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 Books International (Asia) Pte Ltd BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS 1/1/1988- 1/1/1988- INTERIOR DESIGN AND 1001 Home Ideas 6/1/1991 6/1/1991 Magazines Family Media, Inc. DECORATION 3/1/2002- 3/1/2002- Oxford Publishing 20 Century British History 7/1/2009 7/1/2009 Scholarly Journals Limited(England) HISTORY--HISTORY OF EUROPE 33 Charts [33 Charts - 12/12/2009 12/12/2009- 12/12/2009 BLOG] + 6/3/2011 + Other Resources Newstex CHILDREN AND YOUTH--ABOUT COMPUTERS--INFORMATION 50+ Digital [50+ Digital, 7/28/2009- 7/28/2009- 7/28/2009- SCIENCE AND INFORMATION LLC - BLOG] 2/22/2010 2/22/2010 2/22/2010 Other Resources Newstex THEORY IDG 1/1/1988- 1/1/1988- Communications/Peterboro COMPUTERS--PERSONAL 80 Micro 6/1/1988 6/1/1988 Magazines ugh COMPUTERS 11/24/2004 11/24/2004 11/24/2004 Australian Associated GENERAL INTEREST PERIODICALS-- AAP General News Wire + + + Wire Feeds Press Pty Limited UNITED STATES AARP Modern Maturity; 2/1/1988- 2/1/1988- 2/1/1991- American Association of [Library edition] 1/1/2003 1/1/2003 11/1/1997 Magazines Retired Persons GERONTOLOGY AND GERIATRICS American Association of AARP The Magazine 3/1/2003+ 3/1/2003+ Magazines Retired Persons GERONTOLOGY AND GERIATRICS ABA Journal 8/1/1972+ 1/1/1988+ 1/1/1992+ Scholarly Journals American Bar Association LAW ABA Journal of Labor & Employment Law 7/1/2007+ 7/1/2007+ 7/1/2007+ Scholarly Journals American Bar Association LAW MEDICAL SCIENCES--NURSES AND ABNF Journal 1/1/1999+ 1/1/1999+ 1/1/1999+ Scholarly Journals Tucker Publications, Inc. -

Self-Publishing and Collection Development: Opportunities and Challenges for Libraries Robert P

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Books Purdue University Press Fall 9-15-2015 Self-Publishing and Collection Development: Opportunities and Challenges for Libraries Robert P. Holley Wayne State University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, and the Collection Development and Management Commons Recommended Citation Holley, Robert P., Self-Publishing and Collection Development: Opportunities and Challenges for Libraries. (2015). Purdue University Press. (Knowledge Unlatched Open Access Edition.) This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Self-Publishing and Collection Development Opportunities and Challenges for Libraries Charleston Insights in Library, Archival, and Information Sciences Editorial Board Shin Freedman Tom Gilson Matthew Ismail Jack Montgomery Ann Okerson Joyce M. Ray Katina Strauch Carol Tenopir Anthony Watkinson Self-Publishing and Collection Development Opportunities and Challenges for Libraries Edited by Robert P. Holley Charleston Insights in Library, Archival, and Information Sciences Purdue University Press West Lafayette, Indiana Copyright 2015 by Purdue University. All rights reserved. Cataloging-in-Publication data on file at the Library of Congress. Contents Foreword i Mitchell Davis (BiblioLabs) Introduction 1 Robert P. Holley (Wayne State University) 1 E-Book Self-Publishing and the Los Gatos Library: A Case Study 5 Henry Bankhead (Los Gatos Library) 2 Supporting Self-Publishing and Local Authors: From Challenge to Opportunity 21 Melissa DeWild and Morgan Jarema (Kent District Library) 3 Do Large Academic Libraries Purchase Self-Published Books to Add to Their Collections? 27 Kay Ann Cassell (Rutgers University) 4 Why Academic Libraries Should Consider Acquiring Self-Published Books 37 Robert P. -

Participating Publishers

Participating Publishers 1105 Media, Inc. AB Academic Publishers Academy of Financial Services 1454119 Ontario Ltd. DBA Teach Magazine ABC-CLIO Ebook Collection Academy of Legal Studies in Business 24 Images Abel Publication Services, Inc. Academy of Management 360 Youth LLC, DBA Alloy Education Aberdeen Journals Ltd Academy of Marketing Science 3media Group Limited Aberdeen University Research Archive Academy of Marketing Science Review 3rd Wave Communications Pty Ltd Abertay Dundee Academy of Political Science 4Ward Corp. Ability Magazine Academy of Spirituality and Professional Excellence A C P Computer Publications Abingdon Press Access Intelligence, LLC A Capella Press Ablex Publishing Corporation Accessible Archives A J Press Aboriginal Multi-Media Society of Alberta (AMMSA) Accountants Publishing Co., Ltd. A&C Black Aboriginal Nurses Association of Canada Ace Bulletin (UK) A. Kroker About...Time Magazine, Inc. ACE Trust A. Press ACA International ACM-SIGMIS A. Zimmer Ltd. Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Fisicas y Acontecimiento A.A. Balkema Publishers Naturales Acoustic Emission Group A.I. Root Company Academia de Ciencias Luventicus Acoustical Publications, Inc. A.K. Peters Academia de las Artes y las Ciencias Acoustical Society of America A.M. Best Company, Inc. Cinematográficas de España ACTA Press A.P. Publications Ltd. Academia Nacional de la Historia Action Communications, Inc. A.S. Pratt & Sons Academia Press Active Interest Media A.S.C.R. PRESS Academic Development Institute Active Living Magazine A/S Dagbladet Politiken Academic Press Acton Institute AANA Publishing, Inc. Academic Press Ltd. Actusnews AAP Information Services Pty. Ltd. Academica Press Acumen Publishing Aarhus University Press Academy of Accounting Historians AD NieuwsMedia BV AATSEEL of the U.S. -

Quicklaw™ Advanced Terms and Connectors

Quicklaw™ Advanced Terms and Connectors To create a search request with the Quicklaw service, start with terms and phrases Singular and Plural that reflect ideas essential to your research. Then include connectors (such as OR, AND, /5) and other special characters to link the terms and phrases, and to search for With this box checked, Quicklaw automatically finds the plural form of words, word variations. including those that end in us, is, or other irregular forms. For example, bonus also finds bonuses, and child finds children. The View Connectors link is located Truncation on every search screen under the Search Terms box. The truncation symbol ! replaces any number of characters at the end of the word. For example, neglig! finds negligent, negligence, negligible, etc. Wildcard Quicklaw searches for consecutive words as phrases, except when they are separated by connectors. For example, accident AND contributory negligence finds the word The wildcard symbol * replaces a single character at any point in a word. It is accident and the phrase contributory negligence within a document. Use quotation particularly useful if you are unsure of the spelling of a particular word or name. marks to force a phrase search if needed. You can also use multiple wildcards in a single word. For example, advi*e finds both advise and advice. Terms Connectors Terms are the basic units of a search. A term is a single character or group of characters, alphabetic or numeric, with a space on either side. A hyphen is treated as Use connectors to establish logical relationships between words. Connectors operate a space, so a hyphenated term is seen as two terms. -

One of the World's Largest Investment Banks Relies on Lexisnexis® for International Compliance

Case Study: One of the World’s Largest Investment Banks Relies on LexisNexis® for International Compliance Overview One of the world’s largest international investment banks. The Challenge In response to today’s increased regulatory climate, this financial institution performed a self-audit of thousands of international banking transactions completed over the course of two years. The organization analyzed several criteria (e.g., the account holders, banks, country in which these banks reside, recipients, type of transactions) and discovered that it needed to improve its More than 4,000 banks fraud prevention and KYC (Know Your Customer) programs. and financial institutions rely on LexisNexis for The Solution risk management Together with our global partners, LexisNexis® offers this investment bank and compliance. an advanced due diligence solution—LexisNexis® Bridger Insight™ XG —that provides the investigative intelligence necessary to evaluate the legality of international transactions. With access to unparalleled global data and resources, the solution validates the entity and individuals associated with every transaction. The solution facilitates full compliance with the USA PATRIOT Act, and, even more importantly, the LexisNexis solution helps preserve the integrity of the financial institution by identifying suspicious behavior and giving the institution the opportunity to proactively terminate relationships with these people or entities. The Results • Gives the bank the tools it needs to have complete knowledge about international transactions and the people and entities who initiate them. • Provides enhanced due diligence from domestic online sources, domestic jurisdiction and court records and international investigative resources. • Enables the investment bank to fulfill the requirements of the PATRIOT Act and maintain compliance. -

Metadata in the Context of the European Library Project

DC-2002: METADATA FOR E-COMMUNITIES: SUPPORTING DIVERSITY AND CONVERGENCE 2002 Proceedings of the International Conference on Dublin Core and Metadata for e-Communities, 2002 October 13-17, 2002 - Florence, Italy Organized by: Associazione Italiana Biblioteche (AIB) Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze (BNCF) Dublin Core Metadata Initiative (DCMI) European University Institute (IUE) Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza (IMSS) Regione Toscana Università degli Studi di Firenze DC-2002 : metadata for e-communities : supporting diversity and con- vergence 2002 : proceedings of the International Conference on Dublin Core and Metadata for E-communities, 2002, October 13-17, 2002, Florence, Italy / organized by Associazione italiana biblioteche (AIB) … [at al.]. – Firenze : Firenze University Press, 2002. http://epress.unifi.it/ ISBN 88-8453-043-1 025.344 (ed. 20) Dublin Core – Congresses Cataloging of computer network resources - Congresses Print on demand is available © 2002 Firenze University Press Firenze University Press Borgo Albizi, 28 50122 Firenze, Italy http://epress.unifi.it/ Printed in Italy Proc. Int. Conf. on Dublin Core and Metadata for e-Communities 2002 © Firenze University Press DC-2002: Metadata for e-Communities: Supporting Diversity and Convergence DC-2002 marks the tenth in the ongoing series of International Dublin Core Workshops, and the second that includes a full program of tutorials and peer-reviewed conference papers. Interest in Dublin Core metadata has grown from a small collection of pioneering projects to adoption by governments and international organ- izations worldwide. The scope of interest and investment in metadata is broader still, however, and finding coherence in this rapidly growing area is challenging. The theme of DC-2002 — supporting diversity and convergence — acknowledges these changes.