How Big Pakistani Media Groups Are Leading the Surge in Data Journalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East-West Center Association Chapters

04/11/18 EAST-WEST CENTER ASSOCIATION CHAPTERS There are nearly 50 East-West Center Association chapters who are active throughout the Asia Pacific region and the United States. The goal of each chapter is to support the Center by broadening its outreach throughout the region. Chapters facilitate professional networking through a variety of activities, including informal get-togethers, seminars, lectures, and work- shops. Chapters also support the East-West Center by helping recruit qualified participants for its programs, increasing awareness of the Center, raising funds, and carrying out community service projects. Constituent chapters have recently been formed to bring together alumni with special interests. Please contact these chapter leaders or liaisons for information about how you can participate in their local activities: EAST ASIA Seoul Bangkok Prof. Won Nyon Kim Dr. Naris Chaiyasoot Beijing (POP 81-84) (PI 78-83, 85) Dr. Hao Ping Professor Chairman (ASDP 93-96) Korea University Banpu Power Public Company Limited Vice Minister of Education Seoul, Korea Bangkok, Thailand People’s Republic of China Phone: 82-10-9237-7011 Cell: +66-0-818372777 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +66-0-28836778 Communication Liaison: Shanghai E-mail: [email protected] Dr. Hongxia Zhang TBA (RSCH 2009) Dili Program Operations Director, Save the Children China Taipei Mr. Carlos Peloi dos Reis Program Mr. Frank Hung (USET 02-05) Beijing, China (ISI 1965-67) Monitoring and Evaluation Analyst Cell: 86-13621250424 CEO United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], E-mail: [email protected] HPO, Inc. Timor-Leste Taipei, Taiwan Obrigadu Barack, Caicoli Hong Kong Cell: 886-932-150-220 Dili Chapter Leader Liaison: E-mail: [email protected] Timor-Leste Mr. -

MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: PAKISTAN Mapping Digital Media: Pakistan

COUNTRY REPORT MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: PAKISTAN Mapping Digital Media: Pakistan A REPORT BY THE OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS WRITTEN BY Huma Yusuf 1 EDITED BY Marius Dragomir and Mark Thompson (Open Society Media Program editors) Graham Watts (regional editor) EDITORIAL COMMISSION Yuen-Ying Chan, Christian S. Nissen, Dusˇan Reljic´, Russell Southwood, Michael Starks, Damian Tambini The Editorial Commission is an advisory body. Its members are not responsible for the information or assessments contained in the Mapping Digital Media texts OPEN SOCIETY MEDIA PROGRAM TEAM Meijinder Kaur, program assistant; Morris Lipson, senior legal advisor; and Gordana Jankovic, director OPEN SOCIETY INFORMATION PROGRAM TEAM Vera Franz, senior program manager; Darius Cuplinskas, director 21 June 2013 1. Th e author thanks Jahanzaib Haque and Individualland Pakistan for their help with researching this report. Contents Mapping Digital Media ..................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 6 Context ............................................................................................................................................. 10 Social Indicators ................................................................................................................................ 12 Economic Indicators ........................................................................................................................ -

Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates

Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates Syeda Amna Sohail Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates THESIS To obtain the degree of Master of European Studies track Policy and Governance from the University of Twente, the Netherlands by Syeda Amna Sohail s1018566 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Robert Hoppe Referent: Irna van der Molen Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Motivation to do the research . 5 1.2 Political and social relevance of the topic . 7 1.3 Scientific and theoretical relevance of the topic . 9 1.4 Research question . 10 1.5 Hypothesis . 11 1.6 Plan of action . 11 1.7 Research design and methodology . 11 1.8 Thesis outline . 12 2 Theoretical Framework 13 2.1 Introduction . 13 2.2 Jakubowicz, 1998 [51] . 14 2.2.1 Communication values and corresponding media system (minutely al- tered Denis McQuail model [60]) . 14 2.2.2 Different theories of civil society and media transformation projects in Central and Eastern European countries (adapted by Sparks [77]) . 16 2.2.3 Level of autonomy depends upon the combination, the selection proce- dure and the powers of media regulatory authorities (Jakubowicz [51]) . 20 2.3 Cuilenburg and McQuail, 2003 . 21 2.4 Historical description . 23 2.4.1 Phase I: Emerging communication policy (till Second World War for modern western European countries) . 23 2.4.2 Phase II: Public service media policy . 24 2.4.3 Phase III: New communication policy paradigm (1980s/90s - till 2003) 25 2.4.4 PK Communication policy . 27 3 Operationalization (OFCOM: Office of Communication, UK) 30 3.1 Introduction . -

Toward a Peaceful Coexistence of India and Pakistan Suminu Ahmed Consultant, the Asia Foundation, Islamabad, Pakistan

- - m @ 0 a0 0 e 0 a 0 e 8 0 0 0 e0 e 0 0 Issued by Sandia National Laboratories, operated for the United States Department of Energy 0 by Sandia Corporation. NOTICE: This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United 0 either the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of any -of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, makes any e0 implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or 0 represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific 0 commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the e United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors or subcontractors. 0 The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United e States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors. e Printed in the United States of America. This report has been reproduced directly from the best a available copy. ae Available to DOE and DOE contractors from 0 Office of Scientific and Technical Information e e e 0 Prices available from (615) 576-8401, FTS 626-8401 e Available to the public from 0 National Technical Information Service a US Department of Commerce e 5285 Port Royal Rd. Springfjeld, VA 221 61 e NTlS price codes e Printed -

Pakistan Media Legal Review 2019

Pakistan Media Legal Review 2019 Coercive Censorship, Muted Dissent: Pakistan Descends into Silence Annual Review of Legislative, Legal and Judicial Developments on Freedom of Expression, Right to Information and Digital Rights in Pakistan Pakistan Media Legal Review 2019 This report was voluntarily produced by the Institute for Research, Advocacy and Development (IRADA), an Islamabad-based independent research and advocacy organization focusing on social development and civil liberties, with the contribution of Faiza Hassan as research assistant and Muhammad Aftab Alam and Adnan Rehmat as lead researchers. Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................... 1 Attempts to Radicalize Media Regulatory Framework ....................................... 3 Pakistan Media Regulatory Authority (PMRA) .........................................................................3 Media Tribunals ...................................................................................................................................4 i Journalistic and Media Freedoms ........................................................................ 6 Pakistan Media Legal Review 2019 Media Legal Pakistan Murders of Journalists ......................................................................................................................6 Serious Incidents of Harassment and Attacks on Journalists and Media .......................7 Criminal Cases Against Journalists ...............................................................................................8 -

Emergence of Women's Organizations and the Resistance Movement In

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 19 | Issue 6 Article 9 Aug-2018 Defying Marginalization: Emergence of Women’s Organizations and the Resistance Movement in Pakistan: A Historical Overview Rahat Imran Imran Munir Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Imran, Rahat and Munir, Imran (2018). Defying Marginalization: Emergence of Women’s Organizations and the Resistance Movement in Pakistan: A Historical Overview. Journal of International Women's Studies, 19(6), 132-156. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol19/iss6/9 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2018 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Defying Marginalization: Emergence of Women’s Organizations and the Resistance Movement in Pakistan: A Historical Overview By Rahat Imran1 and Imran Munir2 Abstract In the wake of Pakistani dictator General-Zia-ul-Haq’s Islamization process (1977-1988), the country experienced an unprecedented tilt towards religious fundamentalism. This initiated judicial transformations that brought in rigid Islamic Sharia laws that impacted women’s freedoms and participation in the public sphere, and gender-specific curbs and policies on the pretext of implementing a religious identity. This suffocating environment that eroded women’s rights in particular through a recourse to politicization of religion also saw the emergence of equally strong resistance, particularly by women who, for the first time in Pakistan’s history, grouped and mobilized an organized activist women’s movement to challenge Zia’s oppressive laws and authoritarian regime. -

Gwadar: China's Potential Strategic Strongpoint in Pakistan

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons CMSI China Maritime Reports China Maritime Studies Institute 8-2020 China Maritime Report No. 7: Gwadar: China's Potential Strategic Strongpoint in Pakistan Isaac B. Kardon Conor M. Kennedy Peter A. Dutton Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-maritime-reports Recommended Citation Kardon, Isaac B.; Kennedy, Conor M.; and Dutton, Peter A., "China Maritime Report No. 7: Gwadar: China's Potential Strategic Strongpoint in Pakistan" (2020). CMSI China Maritime Reports. 7. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-maritime-reports/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the China Maritime Studies Institute at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in CMSI China Maritime Reports by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. August 2020 iftChina Maritime 00 Studies ffij$i)f Institute �ffl China Maritime Report No. 7 Gwadar China's Potential Strategic Strongpoint in Pakistan Isaac B. Kardon, Conor M. Kennedy, and Peter A. Dutton Series Overview This China Maritime Report on Gwadar is the second in a series of case studies on China’s Indian Ocean “strategic strongpoints” (战略支点). People’s Republic of China (PRC) officials, military officers, and civilian analysts use the strategic strongpoint concept to describe certain strategically valuable foreign ports with terminals and commercial zones owned and operated by Chinese firms.1 Each case study analyzes a different port on the Indian Ocean, selected to capture geographic, commercial, and strategic variation.2 Each employs the same analytic method, drawing on Chinese official sources, scholarship, and industry reporting to present a descriptive account of the port, its transport infrastructure, the markets and resources it accesses, and its naval and military utility. -

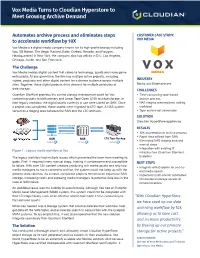

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand Automates archive process and eliminates steps CUSTOMER CASE STUDY: to accelerate workflow by 10X VOX MEDIA Vox Media is a digital media company known for its high-profile brands including Vox, SB Nation, The Verge, Racked, Eater, Curbed, Recode, and Polygon. Headquartered in New York, the company also has offices in D.C, Los Angeles, Chicago, Austin, and San Francisco. The Challenge Vox Media creates digital content that caters to technology, sports and video game enthusiasts. At any given time, the firm has multiple active projects, including videos, podcasts and other digital content for a diverse audience across multiple INDUSTRY sites. Together, these digital projects drive demand for multiple petabytes of Media and Entertainment data storage. CHALLENGES Quantum StorNext provides the central storage management point for Vox, • Time-consuming tape-based connecting users to both primary and Linear Tape Open (LTO) archival storage. In archive process their legacy workflow, the digital assets currently in use were stored on SAN. Once • NAS staging area required, adding a project was completed, those assets were migrated to LTO tape. A NAS system workload served as a staging area between the SAN and the LTO archives. • Tape archive not searchable SOLUTION Cloudian HyperStore appliances PROJECT COMPLETE RESULTS PROJECT RETRIEVAL • 10X acceleration of archive process • Rapid data offload from SAN SAN NAS LTO Tape Backup • Eliminated NAS staging area and manual steps • Integration with existing IT Figure 1 : Legacy media workflow at Vox infrastructure (Quantum StorNext, The legacy workflow had multiple issues which prevented the team from meeting its Evolphin) goals. -

Prospects for Youth-Led Movements for Political Change in Pakistan

January 2012 NOREF Policy Brief Prospects for youth-led movements for political change in Pakistan Michael Kugelman Executive summary This policy brief assesses the potential for two divided and polarised, and religious leadership too types of youth-led political change movements in lacking in charisma and appeal to produce such Pakistan. One is an Arab Spring-like campaign, a movement. Notwithstanding, there are several fuelled by demands for better governance and reasons why Pakistan could witness a religiously new leadership. The other is a religious movement rooted revolution. These include Pakistanis’ akin to the Iranian Revolution of 1979, which seeks intense religiosity and the growing influence in to transform Pakistan into a rigid Islamic state. Pakistan of an Islamist political party that seeks to The brief discusses the presence in Pakistan of install caliphates in Muslim countries. several factors that suggest the possibility of the emergence of an Arab Spring-type movement. Even without youth-led mass change movements, These include economic problems; corruption; urbanisation and political devolution ensure that a young, rapidly urbanising and disillusioned Pakistan will undergo major transformations. While population; youth-galvanising incidents; and, in emphasising that Pakistan must take ultimate Imran Khan, a charismatic political figure capable responsibility over issues of youth engagement, of channelling mass sentiment into political the brief offers several recommendations for how change. Europe can help Pakistani young people engage peacefully in the country’s inevitable process of Pakistan is too fractured, unstable and invested change. These include funding vocational skills in the status quo to launch a mass change certification programmes, financing incentives to movement, and talk of an Arab Spring is keep children in school, supporting civic education misguided in a nation that already experienced courses and sponsoring interfaith dialogue mass protests in 2007. -

Development of Media Policies and Reforms During in Pakistan with Reference to the Democratic and Dictatorship Regime

New Media and Mass Communication www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3267 (Paper) ISSN 2224-3275 (Online) Vol.43, 2015 Development of Media Policies and Reforms during In Pakistan With Reference To the Democratic and Dictatorship Regime *PROF DR MUHAMMAD AHMED QADRI, DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE, UNIVERSITY OF KARACHI **SUWAIBAH QADRI, DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE, UNIVERSITY OF KARACHI ***NASEEM UMER, DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE, UNIVERSITY OF KARACHI ABSTRACT This article studies the comparison between democratic and dictatorship regime in Pakistan, primarilyfocusing on creation of media policies and laws. It is said that development of any society is dependent on number of factors and progressive areas in which media has a vital role. The progressive role of mass media in any society does not only educate and inform the general public but also helps in the formulation of national identity. For the developing countries like Pakistan, the role of media especially becomes crucial when it has to fulfill the requirements of watchdog and simultaneously promotes the national interest and builds positive image of society all around the world. This responsibility of media becomes more difficult when the society has several powerful and influential people, having power to distort, manipulate and biased the opinions of mass media to favor their own good.The article also studies about the opportunities that were present for the media industry and how the new laws and regulations have welcomed the investments with arms wide open. This article, in detail, studies the role of mass media and its growth in democratic and dictatorship regime. Although the general public opinion of the state is always in the favor of the democracy, yet it is quite astonished to know that media’s success was noticeably documented rather in military eras and to be more specific in General Pervez Musharraf’s era. -

The Campaign for Justice: Press Freedom in South Asia 2013-14

THE CAMPAIGN FOR JUSTICE: PRESS FREEDOM IN SOUTH ASIA 2013-14 The Campaign for Justice PRESS FREEDOM IN SOUTH ASIA 2013-14 1 TWELFTH ANNUAL IFJ PRESS FREEDOM REPORT FOR SOUTH ASIA 2013-14 THE CAMPAIGN FOR JUSTICE: PRESS FREEDOM IN SOUTH ASIA 2013-14 CONTENTS THE CAMPAIGN FOR JUSTICE: PRESS FREEDOM IN SOUTH ASIA 2013-14 1. Foreword 3 Editor : Laxmi Murthy Special thanks to: 2. Overview 5 Adeel Raza Adnan Rehmat 3. South Asia’s Reign of Impunity 10 Angus Macdonald Bhupen Singh Geeta Seshu 4. Women in Journalism: Rights and Wrongs 14 Geetartha Pathak Jane Worthington 5. Afghanistan: Surviving the Killing Fields 20 Jennifer O’Brien Khairuzzaman Kamal Khpolwak Sapai 6. Bangladesh: Pressing for Accountability 24 Kinley Tshering Parul Sharma 7. Bhutan: Media at the Crossroads 30 Pradip Phanjoubam S.K. Pande Sabina Inderjit 8. India: Wage Board Victory amid Rising Insecurity 34 Saleem Samad Shiva Gaunle 9. The Maldives: The Downward Slide 45 Sujata Madhok Sukumar Muralidharan Sunanda Deshapriya 10. Nepal: Calm after the Storm 49 Sunil Jeyasekara Suvojit Bagchi 11. Pakistan: A Rollercoaster Year 55 Ujjwal Acharya Designed by: Impulsive Creations 12. Sri Lanka: Breakdown of Accountability 66 Images: Photographs are contributed by IFJ Affiliates. Special thanks to AP, AFP, Getty Images 13. Annexure: List of Media Rights Violations, May 2013 to April 2014 76 and The Hindu for their support in contributing images. Images are also accessed under a CreativeCommons Attribution Non-Commercial Licence. Cover Photo: Past students of the Sri Lanka College of Journalism hold a candlelight vigil at Victoria Park, Colombo, on the International Day May 2014 to End Impunity on November 23, 2013. -

Keeping Faith with the Student-Athlete, a Solid Start and a New Beginning for a New Century

August 1999 In light of recent events in intercollegiate athletics, it seems particularly timely to offer this Internet version of the combined reports of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics. Together with an Introduction, the combined reports detail the work and recommendations of a blue-ribbon panel convened in 1989 to recommend reforms in the governance of intercollegiate athletics. Three reports, published in 1991, 1992 and 1993, were bound in a print volume summarizing the recommendations as of September 1993. The reports were titled Keeping Faith with the Student-Athlete, A Solid Start and A New Beginning for a New Century. Knight Foundation dissolved the Commission in 1996, but not before the National Collegiate Athletic Association drastically overhauled its governance based on a structure “lifted chapter and verse,” according to a New York Times editorial, from the Commission's recommendations. 1 Introduction By Creed C. Black, President; CEO (1988-1998) In 1989, as a decade of highly visible scandals in college sports drew to a close, the trustees of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation (then known as Knight Foundation) were concerned that athletics abuses threatened the very integrity of higher education. In October of that year, they created a commission on Intercollegiate Athletics and directed it to propose a reform agenda for college sports. As the trustees debated the wisdom of establishing such a commission and the many reasons advanced for doing so, one of them asked me, “What’s the down side of this?” “Worst case,” I responded, “is that we could spend two years and $2 million and wind up with nothing to show of it.” As it turned out, the time ultimately became more than three years and the cost $3 million.