Modernization and the Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise and Decline of Catching up Development an Experience of Russia and Latin America with Implications for Asian ‘Tigers’

Victor Krasilshchikov The Rise and Decline of Catching up Development An Experience of Russia and Latin America with Implications for Asian ‘Tigers’ ENTELEQUIA REVISTA INTERDISCIPLINAR The Rise and Decline of Catching up Development An Experience of Russia and Latin America with Implications for Asian `Tigers' by Victor Krasilshchikov Second edition, July 2008 ISBN: Pending Biblioteca Nacional de España Reg. No.: Pending Published by Entelequia. Revista Interdisciplinar (grupo Eumed´net) available at http://www.eumed.net/entelequia/en.lib.php?a=b008 Copyright belongs to its own author, acording to Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 made up using OpenOffice.org THE RISE AND DECLINE OF CATCHING UP DEVELOPMENT (The Experience of Russia and Latin America with Implications for the Asian ‘Tigers’) 2nd edition By Victor Krasilshchikov About the Author: Victor Krasilshchikov (Krassilchtchikov) was born in Moscow on November 25, 1952. He graduated from the economic faculty of Moscow State University. He obtained the degrees of Ph.D. (1982) and Dr. of Sciences (2002) in economics. He works at the Centre for Development Studies, Institute of World Economy and International Relations (IMEMO), Russian Academy of Sciences. He is convener of the working group “Transformations in the World System – Comparative Studies in Development” of European Association of Development Research and Training Institutes (EADI – www.eadi.org) and author of three books (in Russian) and many articles (in Russian, English, and Spanish). 2008 THE RISE AND DECLINE OF CATCHING UP DEVELOPMENT Entelequia.Revista Interdisciplinar Victor Krasilshchikov / 2 THE RISE AND DECLINE OF CATCHING UP DEVELOPMENT C O N T E N T S Abbreviations 5 Preface and Acknowledgements 7 PART 1. -

Beyond Intellectual Insularity: Multicultural Literacy As a Measure of Respect

Beyond Intellectual Insularity: Multicultural Literacy as a Measure of Respect Lisa Taylor Bishops University Michael Hoechsmann McGill University Authors’ Note For their support of this research we are deeply indebted to the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, the Canadian Race Relations Foundation, Bishop’s University, and our participating school boards, schools, teachers, and students. Note des auteurs Pour leur soutien à cette recherche, nous sommes profondément reconnaissants au Conseil de recherche en sciences humaines du Canada, à la Fondation canadienne des relations raciales, à l'Université Bishop's, et aux conseils scolaires qui ont participé ainsi qu'aux écoles, aux enseignants et aux étudiants. Abstract We report on a national survey (942 secondary students, 10 school boards, 5 provinces) that measures what young people know about the histories and the intellectual, political, and cultural legacies of racialized peoples, globally and nationally, and where they learned it (school, media, family, community). Intended as a contribution to, and challenge of, existing frameworks for multicultural education, the research demonstrates the importance of in and out of school learning, and how the various sites of learning resonate differently for particular groups of young people. It demonstrates the key role schools can play for different youth in building, or augmenting, a consistent, common knowledge base. Résumé Nous faisons le rapport d'une enquête nationale (942 élèves du secondaire, 10 conseils scolaires, 5 provinces) qui mesure la connaissance des jeunes, de l'histoire et de l'héritage intellectuel, politique et culturelle des peuples racialisés, mondialement et nationalement, et où ils l'ont appris (l'école, les médias, la famille, la communauté). -

Cultural Stereotypes: from Dracula's Myth to Contemporary Diasporic Productions

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Cultural Stereotypes: From Dracula's Myth to Contemporary Diasporic Productions Ileana F. Popa Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/1345 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cultural Stereotypes: From Dracula's Myth to Contemporary Diasporic Productions A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. Ileana Florentina Popa BA, University of Bucharest, February 1991 MA, Virginia Commonwealth University, May 2006 Director: Marcel Cornis-Pope, Chair, Department of English Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2006 Table of Contents Page Abstract.. ...............................................................................................vi Chapter I. About Stereotypes and Stereotyping. Definitions, Categories, Examples ..............................................................................1 a. Ethnic stereotypes.. ........................................................................3 b. Racial stereotypes. -

O Discurso Da Antropofagia Como Estratégia De Construção Da Identidade Cultural Brasileira

Acta Scientiarum http://www.uem.br/acta ISSN printed: 1983-4675 ISSN on-line: 1983-4683 Doi: 10.4025/actascilangcult.v38i3.31204 O discurso da antropofagia como estratégia de construção da identidade cultural brasileira Weslei Roberto Cândido* e Nelci Alves Coelho Silvestre 1Departamento de Teorias Linguísticas e Literárias, Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Av. Colombo, 5790, 87020-900, Maringá, Paraná, Brasil. 2Departamento de Letras Modernas, Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Maringá, Paraná, Brasil. *Autor para correspondencia. E-mail: [email protected] RESUMO. Este artigo apresenta uma reflexão teórica a respeito do termo ‘deglutição’ utilizado por Oswald de Andrade no Manifesto Antropófago (1928). Nesse manifesto, recortamos o conceito de antropofagia, vocábulo que descreve a devoração do Outro no intuito de absorvê-lo, no afã de assimilar as características das estéticas estrangeiras, e que expressa o impacto dos processos colonizadores na formação da identidade brasileira. Partindo da crítica à civilização europeia (colonialista), Oswald de Andrade, nas entrelinhas de seu discurso sobre a antropofagia, dialoga com as atuais discussões acerca da dependência cultural dos países periféricos. Diante desses apontamentos, nosso propósito é traçar um percurso histórico das leituras e apropriações que o termo ‘deglutição’ sofreu ao longo destes 88 anos, na esteira de estudos de críticos consagrados como Candido, Schwarz e Santiago. Palavras-chave: antropofagia; deglutição; identidade cultural. The discourse of cannibalism as a strategy of building Brazilian cultural identity ABSTRACT. This paper presents a theoretical discussion about the term ‘swallowing’ used by Oswald de Andrade in Manifesto Antropófago (1928). In this manifesto we cut the concept of cannibalism, a word that describes the devouring of the Other in order to absorb it, in his eagerness to assimilate the characteristics of foreign aesthetic, which expresses the impact of colonizing processes in the formation of Brazilian identity. -

Curriculum Vitae

Yongming Zhou Department of Anthropology 1-608-262-2866 (office) 5458 Social Science Building 1-608-663-3906 (home) University of Wisconsin-Madison Fax: 1-608-265-4216 Madison, Wisconsin 53706 Email: [email protected] I. FORMAL EDUCATION 1997 Ph.D Duke University (Cultural Anthropology) 1987 M.A. Nanjing University (Chinese) 1984 B.A. Nanjing University (Chinese) II. TITLE OF DISSERTATION Ph.D: Nationalism, History and State Building: Anti-Drug Crusades in Modern China, 1924—1997. III. POSITIONS HELD A. Teaching Positions 2010-present Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Wisconsin-Madison 2005-2010 Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1999- 2005 Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1998 Fall Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of History, Duke University 1996 Fall Visiting Lecturer, Curriculum in Asian Studies, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill B. Affiliations Director, Center for Anthropological Research, Chongqing University Center for East Asian Studies, UW-Madison Center for Culture, History, and Environment, UW-Madison Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, UW-Madison 1 IV. SPECIAL HONORS AND AWARDS 2013-present Founder and Chair of Selection Committee, China Fieldwork Fellowships for Graduate Students 2014-18 Senior Fellow, Institute for Research in the Humanities, UW-Madison 2012 President, The Midwest Conference on Asian Affairs 2012 Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Post-Fellowship Award 2010 American Council of Learned Societies, Collaborative Research Fellowship, 2008 spring Senior Visiting Fellow, Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore 2008 Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, New Directions Fellowship 2004 Fellow, Institute for the Research in Humanities, UW-Madison 2003 summer Mellon Fellow, Needham Research Institute, Cambridge, England 2001-02 Fellow, The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars 2001-02 Fellowship, National Program for Advanced Study and Research in China. -

Community Chapter Draft 2.0 Sep 03

-1- “A Century of Difference” Working Paper THE SURVEY RESEARCH CENTER University of California, Berkeley 2538 Channing Way Berkeley, CA 94720-5100 -------------------------------------------- http://ucdata.berkeley.edu/rsfcensus 510-643-6874 510-643-8292 Different Places, Different People: 1 The Redrawing of America’s Social Geography by Claude S. Fischer ([email protected]) Michael Hout ([email protected]) DRAFT 2.0 of September, 2003 1 This draft working paper will be developed into a chapter of a book in progress commissioned by the Russell Sage Foundation as part of the “Century of Difference” project. Other working papers can be found at the web site above. This work was critically assisted and much improved by Jon Stiles and Gretchen Stockmayer. American Sociological Association Disclaimer: Copyright 2003 . All rights reserved. This paper is for the reader's personal use only. This paper may not be quoted, reproduced, distributed, transmitted or retransmitted, performed, displayed, downloaded, or adapted in any medium for any purpose, including, without limitation, teaching purposes, without the authors’ express written permission. Permission requests should be directed to [email protected]. -2- Different Places, Different People:The Redrawing of America’s Social Geography In 1900, Americans were bitterly divided by region. They remembered the Civil War – it was as recent to them as the Vietnam War is to us in 2003 – and their memories were regularly refreshed by politicians “waving the bloody shirt.” Even before the War Between the States, Americans had harped on cultural differences between North and South, East and West. Many Midwesterners, for example, used the verb “to yankee” to mean to cheat. -

Globalization and Russia V.I

Globalization and Russia V.I. Dobrenkov No social phenomenon can be considered outside the globalization context any more in modern social science. The essence of globalization, to my mind, is, in the shortest definition, that it is an objective, natural process of integration of the mankind. Globalization appears in the fact that social processes in one part of the world determine what is going on in all other parts of the world in a more influential way and are themselves affected by the latter. Space compression takes place, time is being pressed down, geographical and international borders become more transparent and easy to overcome. Flows of goods, services, information, people, and capital circulate around the planet with growing intensity. Various forms of union of peoples have been known since the ancient times, but the processes of integration of the mankind only embrace the whole planet for the first time in history in the end of the 20th century due to wild changes in communication means, economic, political, spiritual spheres. One can only speak about globalization in a strict sense of this word since that time. Globalization appears as a multilevel and many-sided system of various integration phenomena. The main ones are the emergence of global communication, global economics, global politics, global culture, a global language, and a global way of life. But it would be insufficient to restrict oneself with stating these changes. Globalization is seen as an extremely contradictory and complex process, if analyzed more thoroughly. On the one hand, globalization is a regular and necessary process of integration of the mankind, accompanied by the growth of the quality of life and well-being level of the mankind, accelerating of the economic and political development of countries, activation of interchange with technological, scientific, and cultural achievements among various countries and peoples. -

THE SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGICAL FIELD EXPERIENCE* George M

THE SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGICAL FIELD EXPERIENCE* George M. Foster University of California, Berkeley Contemporary social anthropology differs from the other social sciences in its emphasis on the field experience, a data-gathering and theory-generating technique in which, in classic form, the scientist im- merses himself in a research setting in a way unparalleled in other dis- ciplines. Over a period of months or even years, he lives a life--24 hours a day--which is quite distinct from his normal home life. Field work as a way of gathering data is, of course, by no means exclusive to anthropology. It is a technique also used by geographers, geologists, botanists, and zoologists, to name a few. But anthropological field work differs from that of these fields in the degree of personal involvement which the investigator must achieve with the local people, and in the psychological adjustments he must make if he is to be successful. In most other disciplines characterized by field trips, scientists do not necessarily need fluent control of local languages; interpreters usually can serve their needs. And while they must establish contact with local people for food and other necessities, their lives usually are rather separated from those of the indigenous population. Probably they will set up tent camps, cook their own food, and otherwise minimize contact with the human element in their field environment. In other words, although anthropology shares the field trip technique with a number of other disciplines, the nature of field work in these subjects is quite different from that of social anthropology. It is therefore important for anthropologists to understand the special qualities of their field experience, its purposes, the methodological as- sumptions that underlie it, and the ways in which it influences the de- velopment of their theory. -

Introductory Essay “It Has Been Justly Remarked That a Nation's Civilization

Introductory Essay “It has been justly remarked that a nation’s civilization may be estimated by the rank which females hold in society. If the civilization of China be judged of by this test, she is surely far from occupying that first place which she so strongly claims.” Chinese Repository, vol. 2 (Nov. 1833), p. 313. This statement, which introduced an article on Chinese women in a missionary journal, is representative of Western journalistic writing about Chinese women in the 19th century. In two brief sentences, this comment simultaneously locates China and Chinese women in a state of cultural backwardness and places the invisible Western reader in the position of all-knowing observer. As the sources in this module illustrate, this fundamental distinction between the Western and the Chinese was expressed in both implicit and explicit ways in the foreign press. Chinese women became representative objects for Western observers, proof of the failings of Chinese culture and the necessity of Christian conversion. Described as victims of their own society, in these pieces Chinese women were in fact victims of a foreign pen, deprived of any agency in their own existence and judged with a sympathy born of arrogance. The representations of Chinese women in these journalistic accounts bear uncanny similarities to popular conceptions about the “place” of women in Confucian societies today—primarily that they are passive, obedient, and oppressed. A guided critical analysis of samples from 19th-century Western writing about Chinese women is one means of confronting popular stereotypes about Chinese/Asian women that abound in Western culture. -

Directions of Financial Security Enforcement in the Central Asia Countries

,nternational Journal of ,nnovative Technologies in Economy ,SS1 2412-8368 D,RECT,21S 2F ),1A1C,A/ SEC8R,TY E1)2RCE0E1T I1 THE CE1TRAL AS,A C281TR,ES 1urymova Saule, Yessentay Aigerim .azakhstan, Almaty, ,nstitute of Economics of the Committee of Science of the 0inistry of Education and Science of the Republic of .azakhstan, 3hD doctoral student !wd//[9 /ECh !.^dw!/d Received 06 0arch 2018 Article is devoted to the assessment and analysis of the level of financial Accepted 04 April 2018 security of the economies of the countries of Central Asia, and the definition 3ublished 01 0ay 2018 of the criteria for the development of the financial system, its support and approval in the current economic situation. The urgency of the article is due Y9zthw5^ to the fact that in the current situation the proElem of ensuring financial security Eecomes systemic, it affects and connects individual countries, government, regions, economic entities, politics, economy, finance, etc. ,ntegration of finance, countries with a guarantee of financial security will contriEute to the security, sustainaEle development of the region's economy to financial risks. management, indicators, Eenchmarks, economy © 2018 The Authors. 9irtually there is no aspect of the country's national security that does not directly depend on the level of its financial security. At the same time, the level of financial security itself mostly depends on the level of other aspects of national security. Consideration of interrelations and dependence between various aspects of national security allows finding measures to prevent or overcome threats to the national interests. The dependence of all aspects of the country's national security on its financial security is at first glance extremely simple: the lack of financial resources leads to underfunding of the most urgent needs in various sectors of the economy and poses a threat to national security. -

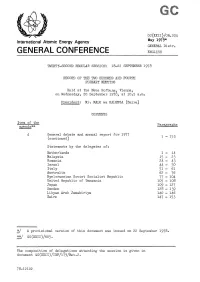

Gc(22)/Or.204

GC(XXII)/OR.204 International Atomic Energy Agency May 1979* GENERAL Distr. GENERAL CONFERENCE ENGLISH TWENTY-SECOND REGULAR SESSION: 18-22 SEPTEMBER I978 RECORD OF THE TWO HUNDRED AND FOURTH PLENARY MEETING Held at the Neue Hofburg, Vienna, on Wednesday, 20 September 1978, at 10.5 a.m. President: Mr. MALU wa KALENGA (Zaire.) CONTENTS Item of the Paragraphs agenda** 4 General debate and annual report for 1977 (continued) 1 - 153 Statements by the delegates of: Netherlands 1 14 Malaysia .15 23 Romania 24 43 Israel 44 50 Italy 51 61 Australia 62 76 Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic 77 104 United Republic of Tanzania 105 108 Japan 109 127 Sweden 128 139 Libyan Arab Jamahiriya 140 146 Zaire 147 153 */ A provisional version of this document was issued on 22 September 1978. **/ GC(XXII)/605. The composition of delegations attending the session is given in document GC(XXII)/INF/l79/Rev.2. 78-12102 GC(XXII)/OR.204 GC(XXII)/OR.204 page 2 page 3 GENERAL DEBATE AND ANNUAL REPORT FOR 1977 (continued) Expressing appreciation of the valuable contributions made by the Agency's Secretariat to the work of INFCE, he urged all INFCE participants to avail 1. Mr. de BQSR (Netherlands) said that the current session of the General themselves as much as possible of the Agency's services and experience in Conference was taking place at a time when the peaceful uses of nuclear energy order to avoid duplication of efforts and to-save time and resources in bringing were being intensely debated. It was regrettable there were more misunderstand INFCE to a positive conclusion. -

Locating Culture, Identity, and Human Rights Symposium in Celebration Of

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Faculty Scholarship 1998 Introduction: Locating Culture, Identity, and Human Rights Symposium in Celebration of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: Introduction Catherine Powell Fordham University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Human Rights Law Commons Recommended Citation Catherine Powell, Introduction: Locating Culture, Identity, and Human Rights Symposium in Celebration of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: Introduction, 30 Colum. Hum. Rts. L. Rev. 201 (1998-1999) Available at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship/412 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYMPOSIUM IN CELEBRATION OF THE FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF THE UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS INTRODUCTION: LOCATING CULTURE, IDENTITY, AND HUMAN RIGHTS by Catherine Powell' As we celebrate the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the idea of human rights endures. The human rights idea was honored at a conference organized by the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, held at Fordham Law School on December 10-12, 1999, to commemorate the first fifty years of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The four pieces that follow were presented at the conference as part of a panel addressing one of the central philosophical concerns regarding the human rights project: its universality.