Charlie Hurley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST Lot Description An 1896 Athens Olympic Games participation medal, in bronze, designed by N Lytras, struck by Honto-Poulus, the obverse with Nike 1 seated holding a laurel wreath over a phoenix emerging from the flames, the Acropolis beyond, the reverse with a Greek inscription within a wreath A Greek memorial medal to Charilaos Trikoupis dated 1896,in silver with portrait to obverse, with medal ribbonCharilaos Trikoupis was a 2 member of the Greek Government and prominent in a group of politicians who were resoundingly opposed to the revival of the Olympic Games in 1896. Instead of an a ...[more] 3 Spyridis (G.) La Panorama Illustre des Jeux Olympiques 1896,French language, published in Paris & Athens, paper wrappers, rare A rare gilt-bronze version of the 1900 Paris Olympic Games plaquette struck in conjunction with the Paris 1900 Exposition 4 Universelle,the obverse with a triumphant classical athlete, the reverse inscribed EDUCATION PHYSIQUE, OFFERT PAR LE MINISTRE, in original velvet lined red case, with identical ...[more] A 1904 St Louis Olympic Games athlete's participation medal,without any traces of loop at top edge, as presented to the athletes, by 5 Dieges & Clust, New York, the obverse with a naked athlete, the reverse with an eleven line legend, and the shields of St Louis, France & USA on a background of ivy l ...[more] A complete set of four participation medals for the 1908 London Olympic -

Read PDF « Little Book of Arsenal (Paperback) WIKRUJWMMF8L

IXKRR9QI9TBY > PDF # Little Book of Arsenal (Paperback) Little Book of A rsenal (Paperback) Filesize: 8.37 MB Reviews Completely one of the best ebook I actually have possibly study. It can be writter in simple phrases and not confusing. You can expect to like the way the author write this book. (Josefa Ebert) DISCLAIMER | DMCA IRA9FW4YLTHH ~ eBook > Little Book of Arsenal (Paperback) LITTLE BOOK OF ARSENAL (PAPERBACK) To read Little Book of Arsenal (Paperback) PDF, remember to follow the hyperlink listed below and download the ebook or have access to other information that are relevant to LITTLE BOOK OF ARSENAL (PAPERBACK) ebook. Carlton Books Ltd, United Kingdom, 2013. Paperback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book. The Oicial Little Book of Arsenal is a truly explosive collection of words of wit and wisdom by and about the managers, players and oicials who have passed through the marble halls of Highbury and the Gunners palatial new home at the Emirates stadium. From Herbert Chapman to Arsene Wenger, via the likes of George Allison, Bertie Mee and George Graham, from one Double to another, and from Ted Drake to Theo Walcott, Liam Brady to Santi Carzola, and Bernard Joy and Tony Adams to Dennis Bergkamp and Thierry Henry, here are more than 165 hot-shot quotations for the avid Gooner. Enjoy the humour and poignancy as The Oicial Little Book of Arsenal takes the reader through the highs and lows of the club s fortunes on the pitch and savour some great moments as double-winning goalkeeper Bob Wilson said, Once an Arsenal man, always an Arsenal man. -

19 3 7 Copyright May 20, 1937

• I *> THE DON 19 3 7 Copyright May 20, 1937 John Conway, Sdttor Charles Scully, Manager THE DON 19 3 7 Published by the Associated Students UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO Vol ume I t DEDICATION DEATH CAME . I FOR ONE: from cloudless skies, struck sparkling waters, stilled rippling laughter. ROY WALTER O'FARREU. FOR THE OTHER: on leaden wings, slowly, burying an un seen scythe in a generous heart To both of these who have gone on: Roy O'Farrell and Robert Emmet Moore WE WHO REMAIN DEDICATE THIS VOLUME. ROBERT EMMET MOORE I University Book One I REV. JAMES J. LYONS S.J. REV. HAROLD E. RING S.J. Dean President F c u 1 t y W. BRYCI- ATKINSON, M.S. FREDERICK L. BROWN Chemistry Music JAMES BAKER BASSETT, M.A., I.E. B. CORNELIUS ALOYSIUS BUCKLEY, S.J. History History, Religion AUGUSTIN RUSSELL BERTI, M.A., LL.M. RAYMOND IGNATIUS BUTLER, S.J. English Classics, Education BERNARD BIERMANN, J.U.D. WALLACE BRUCE CAMERON, MA. Political Science. German Economics J. BRENT BODEISH, A.B. LL.M. C. HAROLD CAUI.FIELD, A.B., LL.D. Law Law CAMILLUS EUGENE BRANCHI, M.A., DNS. RODERICK ALEXANDER CHISHOLM, B.C.E. Italian, Spanish Geology, Mathematics WILLIAM G. BREY ALEXANDER JOSEPH CODY, S.J. Major Coast Artillery, U.S.A. English ALEXANDER BRILL, A.B. JAMES JOSEPH CONLON, S.J. Spanish Chemistry [9] . F u 1 t y PRESTON DEVINE, M.A., LL.B. JOHN JOSEPH GEARON, S.J. Political Science Classics, Religion GREGORY GEORGE DEXTER, MBA. GERALD JOSEPH GEARY, Ph.D. -

Sample Download

THE HISTORYHISTORYOF FOOTBALLFOOTBALL IN MINUTES 90 (PLUS EXTRA TIME) BEN JONES AND GARETH THOMAS THE FOOTBALL HISTORY BOYS Contents Introduction . 12 1 . Nándor Hidegkuti opens the scoring at Wembley (1953) 17 2 . Dennis Viollet puts Manchester United ahead in Belgrade (1958) . 20 3 . Gaztelu help brings Basque back to life (1976) . 22 4 . Wayne Rooney scores early against Iceland (2016) . 24. 5 . Brian Deane scores the Premier League’s first goal (1992) 27 6 . The FA Cup semi-final is abandoned at Hillsborough (1989) . 30. 7 . Cristiano Ronaldo completes a full 90 (2014) . 33. 8 . Christine Sinclair opens her international account (2000) . 35 . 9 . Play is stopped in Nantes to pay tribute to Emiliano Sala (2019) . 38. 10 . Xavi sets in motion one of football’s greatest team performances (2010) . 40. 11 . Roger Hunt begins the goal-rush on Match of the Day (1964) . 42. 12 . Ted Drake makes it 3-0 to England at the Battle of Highbury (1934) . 45 13 . Trevor Brooking wins it for the underdogs (1980) . 48 14 . Alfredo Di Stéfano scores for Real Madrid in the first European Cup Final (1956) . 50. 15 . The first FA Cup Final goal (1872) . 52 . 16 . Carli Lloyd completes a World Cup Final hat-trick from the halfway line (2015) . 55 17 . The first goal scored in the Champions League (1992) . 57 . 18 . Helmut Rahn equalises for West Germany in the Miracle of Bern (1954) . 60 19 . Lucien Laurent scores the first World Cup goal (1930) . 63 . 20 . Michelle Akers opens the scoring in the first Women’s World Cup Final (1991) . -

Brian Clough and Peter Taylor

Made in Derby 2018 Profile Brian Clough and Peter Taylor Brian Clough and Peter Taylor. Two names that will always be associated with Derby County. They met as young players – Brian a centre-forward and Peter a goalkeeper – at Middlesbrough FC, where they played together for six years. With a shared passion for the beautiful game they formed a friendship that would take them to the very top of English and European football. They first joined forces as managers at Hartlepool United but it was at Derby County where the dynamic duo, as they were known, had their first taste of the big time. Many of Derby's greatest names were signed in the Clough-Taylor era: Roy McFarland, John O'Hare, Alan Hinton, John McGovern, Willie Carlin, Dave Mackay, Colin Todd and Archie Gemmill to name a few. The two managers and their magnificent team took the Rams to the very top, winning the Division One Championship in 1972 and reaching the European Cup semi-finals. The pair controversially resigned early in the 1973-74 season and the partnership broke up briefly, only be reunited at Nottingham Forest in 1976 where they won many accolades, including two European Cups. But it was at Derby County where the partnership first flourished and Taylor’s daughter, Wendy Dickinson, in a biography of her father, said: “When dad and Brian arrived at the Baseball Ground in May, 1967 it was as if Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid had ridden into town, all guns blazing. These two bright young upstarts were a breath of fresh air at a club that was stuck in the past.” She said her dad was “passionate” about managing Derby and added: “My mum remembers driving down to Derby for the first time and dad said, ‘I wonder what the supporters are like?’ He later said he thought they were the best in the country.” The success of that Derby County team affected everyone in the town and amazing results week after week sent people to work on a Monday morning with a spring in their step. -

Baggie Shorts

“you just don’t seem to understand” BAGGIE SHORTS ISSUE 9 - SEASON 2016/17 WEST BROMWICH ALBION LONDON SUPPORTERS CLUB Welcome... department and the dietician. Having celebrated virtually every member of Arsenal Inc., the announcer said “and ...to the latest edition of Baggie Shorts. At the time of a big welcome to our guests, West writing, we have reached the magic 40 points and have A day in the life of an Albion Bromwich Albion” and then the referee arrived at that point in the season when Sam Field gets to fan aged 13 and a half blew the whistle and the carnage com- play for three minutes and the usual doubts set in. 4 by Anthony Nash menced. Happy Days! In an effort to illuminate those doubts, we’ve commis- Arsenal v West Bromwich Happy Days also for Patrick Fahey (The Albion Match Report sioned Albion-nut and statistician Jon Want to analyse story of an Executive Steward), who tells by Aidan Rose the empirical data (see The Pulis Effect: What the Stats 6 us how he secured his dream match Say). Jon’s appearance in these pages is thanks largely day job and for Anthony Nash (Foot- to the dogged determination of Glenn Hess, for it was The story of an Executive ball Through The Ages: In search of the Glenn’s plan to lure Jon to The Exmouth Arms and thence Steward Golden Age) who shares his memories to cause his inebriation by the liberal application of ales, 7 by Patrick Fahey of his first Albion away day and reflects the better to secure his cooperation. -

1987-04-05 Liverpool

ARSENAL vLIVERPOOL thearsenalhistory.com SUNDAY 5th APRIL 1987 KICK OFF 3. 5pm OFFICIAL SOUVENIR "'~ £1 ~i\.c'.·'A': ·ttlewcrrJs ~ CHALLENGE• CUP P.O. CARTER, C.B.E. SIR JOHN MOORES, C.B.E. R.H.G. KELLY, F.C.l.S. President, The Football League President, The Littlewoods Organisation Secretary, The Football League 1.30 p.m. SELECTIONS BY THE BRISTOL UNICORNS YOUTH BAND (Under the Direction of Bandmaster D. A. Rogers. BEM) 2.15 p.m. LITTLEWOODS JUNIOR CHALLENGE Exhibition 6-A-Side Match organised by the National Association of Boys' Clubs featuring the Finalists of the Littlewoods Junior Challenge Cup 2.45 p.m. FURTHER SELECTIONS BY THE BRISTOL UNICORNS YOUTH BAND 3.05 p.m. PRESENTATION OF THE TEAMS TO SIR JOHN MOORES, C.B.E. President, The Littlewoods Organisation NATIONAL ANTHEM 3.15 p.m. KICK-OFF 4.00 p.m. HALF TIME Marching Display by the Bristol Unicorns Youth Band 4.55 p.m. END OF MATCH PRESENTATION OF THE LITTLEWOODS CHALLENGE CUP BY SIR JOHN MOORES Commemorative Covers The official commemorative cover for this afternoon's Littlewoods Challenge Cup match Arsenal v Liverpool £1.50 including post and packaging Wembley offers these superbly designed covers for most major matches played at the Stadium and thearsenalhistory.com has a selection of covers from previous League, Cup and International games available on request. For just £1.50 per year, Wembley will keep you up to date on new issues and back numbers, plus occasional bargain packs. MIDDLE TAR As defined by H.M. Government PLEASE SEND FOR DETAILS to : Mail Order Department, Wembley Stadium Ltd, Wembley, Warning: SMOKING CAN CAUSE HEART DISEASE Middlesex HA9 ODW Health Departments' Chief Medical Officers Front Cover Design by: CREATIVE SERVICES, HATFIELD 3 ltlewcms ARSENAL F .C. -

Day 1, Wednesday 24 June, Lots 1-500

DAY 1, WEDNESDAY 24 JUNE, LOTS 1-500 Lot Description Estimate Trade cards, A&BC Gum, Footballers, Quiz 1-49 (set, 49 cards) (gd/vg, checklist £60-70 1 unmarked) (49) (plus BP*) Trade cards, A&BC Gum, Footballers, Quiz 50-98 (set, 49 cards) (gd/vg, £80-120 2 checklist unmarked) (49) (plus BP*) Trade cards, A&BC Gum, Footballers (Black back, 1-42) (set, 42 cards) (gd/vg, £50-70 3 checklist unmarked) (42) (plus BP*) Trade cards, A&BC Gum, Footballers (Black back, 43-84) (set, 42 cards) (gd/vg, £80-120 4 checklist unmarked) (42) (plus BP*) Trade cards, A&BC Gum, Footballers (Did You Know?, Scottish, 1-73) (set, 73 £80-100 5 cards) (ex, checklist unmarked) (73) (plus BP*) Trade cards, A&BC Gum, Footballers (Did You Know?, Scottish, 74-144) (set, 71 £200-300 6 cards) (ex, checklist unmarked) (71) (plus BP*) Trade cards, A&BC Gum, Footballers (Green back, Scottish, Rub Coin) (set, 132 £250-350 7 cards) (vg, checklist unmarked) (132) (plus BP*) £40-60 8 Trade cards, News Chronicle, Footballers, Bury (set, 13 cards) (vg) (plus BP*) £40-60 9 Trade cards, News Chronicle, Footballers, Exeter (set, 12 cards) (vg) (plus BP*) £40-60 10 Trade cards, News Chronicle, Footballers, Leicester City (set, 12 cards) (vg) (plus BP*) £40-60 11 Trade cards, News Chronicle, Footballers, Lincoln City (set, 11 cards) (vg) (plus BP*) Trade cards, News Chronicle, Footballers, Northampton Town (set, 12 cards) £40-60 12 (vg) (plus BP*) Trade cards, News Chronicle, Footballers, Rotherham United (set, 12 cards) £40-60 13 (vg) (plus BP*) £40-60 14 Trade cards, News Chronicle, Footballers, Southampton (set, 12 cards) (vg) (plus BP*) Trade cards, News Chronicle, Footballers, Wolverhampton Wanderers (set, 12 £40-60 15 cards) (vg) (plus BP*) Cigarette cards, Smith's, Footballers (Brown back, 1906), Aston Villa, four £60-80 16 cards, no 3 J. -

Thearsenalhistory.Com F

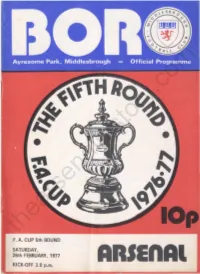

thearsenalhistory.com F. A. CUP Sth ROUND SATURDAY, 26th FEBRUARY I 1977 ARSEftAl KICK-OFF 3.0 p.m. mlDDlESBROUGH P.C. Half•Timc & ATHlETIC CO. lTD. TE Am Sco1c1 AYRESOME PARK. MIDDLESBROUGH . CLEVELAND TS1 4PE . Telephone: 89659/ 85996 DIRECTORS: C . Amer (Chairman). Dr. U . N. Philli ps (V ice-Cha irman) . G . T . Ki t c h ing . E. V arl e y . J . D . Hatfield . M . McCul l agh , K. C . Amer. E. K. Varley . MANAGER: J . Charlton O .B.E. SHEET SECRETARY : T . H . C . Green . ASSISTANT MANAGER : H . Shepherd son M .B. E. KEY No. 1 ORANGE C LUB HONOURS: A Aston Villa v Port Va le Second D i v i s i on Champions 1926/ 27-1928/ 29- 1973/ 74 A nglo-Scottish Cup Winners 1915/ 76 B Cardiff v Everton 8010 C Derby v Blackburn R. D Wolves v Chester as something fresh. Arse nal w ill be a 1 Pat CUFF E Leeds v Manchester C. different kettle of fish today and there is F Liverpool v Oldham mc11agc f1om no way they w ill come and play the way 2 John CRAGGS they did 11 days ago. it is qu ite probable that the injured players w ill be returning 3 Terry COOPER to the team improving their all-round 4 Graeme SOUNESS KEY No. 2 GREEN the manage•: strength and mobility. A Southampton v Manchester U. B Coventry v West Brom. Your support in recent matches has 5 Stuart BOAM THE CHANGING FORTUNES been tremendous and I hope that by the C Q.P.R . -

Busby's Babes

BUSBY'SBABES Barnsley's Tommy Taylor led the front line. On a snow shrouded sixth of February Accompanied by 'owd boss Walter Crickmer, nineteen fifty-eight, the 'Lord Burghley' Trainer Tom Curry and team coach Bert Whalley, Ambassador took off an hour late. who magic-sponged their shins when they got From Belgrade to Manchester after a three-all hurt. draw they landed in Munich to wait for a thaw. New dad Bela Miklos, fan Willie Satinoff, Europe's Top Cup...Semi-finals now waiting, Captain Rayment and steward Tommy Cable... sat on the runway cold engines hesitating... All now sit on God's top table... with Frank Swift Up slippery steps, banter and card schools dealt, and seven sports writer mates still typing up big pot luck where they sat, for a tight seatbelt. match updates. B...E... A... six-o-nine roared into life while Bela Miklos held tight to his wife. Red Star pleaded with UEFA... 'Respect! Wise up! Award United the Champions Cup. Rolled twice through deep slush to 85 knots... Alas a 5-2 with Milan ended our run Pressure gauge low... the plane had to stop. a heartbroken semi, it was over and done. All off for a brew, Mark Jones lit his pipe, late going home, but nobody griped. Winger Johnny Berry, half back 'Twiggy' Fastened overcoats, downed stewed tea Blanchflower broke their bones lost footballing due now for lift off at fifteen-o-three. powers, lucky to rise from their hospital beds Captain Thain and Co-Pilot Ken slowly revved up never again pulled on Red Devil's Red. -

Genesis of Football Support

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Northumbria Research Link Northumbria Research Link Citation: Dixon, Kevin (2014) Football fandom and Disneyisation in late-modern life. Leisure Studies, 33 (1). pp. 1-21. ISSN 0261-4367 Published by: Taylor & Francis URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2012.667819 <https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2012.667819> This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/43466/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/pol i cies.html This document may differ from the final, published version of the research and has been made available online in accordance with publisher policies. To read and/or cite from the published version of the research, please visit the publisher’s website (a subscription may be required.) Football Fandom and Disneyization in Late Modern Life In 1999 Alan Bryman coined the term Disneyization to make the case that more and more sectors of social and cultural life are coming to take on the manifestations of a commercial style theme park. -

Haringey Borough Football Club Founded 1907 (As Tufnell Park F.C) Ground: Cvs Van Hire Stadium, Coles Park, White Hart Lane, London, N17 7Jp

HARINGEY BOROUGH FOOTBALL CLUB FOUNDED 1907 (AS TUFNELL PARK F.C) GROUND: CVS VAN HIRE STADIUM, COLES PARK, WHITE HART LANE, LONDON, N17 7JP HARINGEY BOROUGH v QPR UNDER 23s (Friendly) TUESDAY 8TH SEPTEMBER 2020 - 7.00pm Issue 2608 HARINGEY BOROUGH FOOTBALL CLUB COLES PARK, WHITE HART LANE, LONDON, N17 7JP CLUB WEBSITE: www.haringeyboroughfc.net FOUNDED 1907: Affiliated to the London Football Association PERSONS OF SIGNIFICANT INTEREST: Aki ACHILLEA /George KILIKITA STADIUM MANAGER: Tom LOIZOU Telephone: 07956 284480 FOOTBALL SECRETARY: John BACON Telephone: 01707 873187 EMAIL: [email protected] HARINGEY BOROUGH FC LTD: Company Reg. No. 07237358 Reg. Office: 35-37 Station Road, Chingford, London E4 7BJ HONOURS BOARD TUFNELL PARK:- FA Amateur Cup - finalists 1919/20; semi - finalists 1911/12 & 1913/14 Spartan League runners up 1910/11 London Senior Cup winners 1912/13 & 1923/24 Athenian League winners 1913/14 Middlesex Charity Cup winners 1943/44 EDMONTON:- Delphian League Emergency Competition winners 1962/63 Athenian League Division 2 Cup winners 1967/68 and 1968/69 Athenian League Division 2 runners up 1969/70 WOOD GREEN TOWN:- London Junior Cup runners up 1907/08 London League Division 1(B) winners 1909/10 Spartan League Division 1 runners up 1937/38 Middlesex Senior League winners 1940/41 HARINGEY BOROUGH:- London Senior Cup winners 1990/91 Spartan League Cup runners up 1990/91 Spartan South Midlands League Premier Division Cup runners up 1997/98 Southern Counties Floodlit Youth League (Under 18) Nemean Div’n Champions 2004/05 &