Cover Pursuits a Behind-The-Scenes Look at the Lengths Scientists Will Go to Get Their Research on the Cover of Science, Cell Or Nature FEATURES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2021 Bulletin

Advancing Access to Civil Justice STEPS TOWARD INTERNATIONAL CLIMATE GOVERNANCE Featuring William Nordhaus, Pinelopi Goldberg, and Scott Barrett HONORING WILLIAM LABOV, RUTH LEHMANN , AND GERTRUD SCHÜPBACH SPRING 2021 SELECT UPCOMING VIRTUAL EVENTS May 6 A Conversation with Architect 27 Reflections on a Full, Consequential, Jeanne Gang and Lucky Life: Science, Leadership, Featuring: Jeanne Gang and Education Featuring: Walter E. Massey (left) in conversation with Don Randel (right) June 14 Lessons Learned from Reckoning with Organizational History Featuring: John J. DeGioia, Brent Leggs, Susan Goldberg, Claudia Rankine, and Ben Vinson 13 Finding a Shared Narrative Hosted by the Library of Congress Featuring: Danielle Allen, winner of the Library’s 2020 Kluge Prize Above: “Our Common Purpose” featuring the Juneteenth flag with one star. Artist: Rodrigo Corral For a full and up-to-date listing of upcoming events, please visit amacad.org/events. SPRING 2021 CONTENTS Flooding beside the Russian River on Westside Road in Healdsburg, Sonoma County, California; February 27, 2019. Features 16 Steps Toward International 38 Honoring Ruth Lehmann and Gertrud Climate Governance Schüpbach with the Francis Amory Prize William Nordhaus, Pinelopi Goldberg, and Scott Barrett Ruth Lehmann and Gertrud Schüpbach 30 Honoring William Labov with the Talcott Parsons Prize William Labov CONTENTS 5 Among the contributors to the Dædalus issue on “Immigration, Nativism & Race” (left to right): Douglas S. Massey (guest editor), Christopher Sebastian Parker, and Cecilia Menjívar Our Work 5 Dædalus Explores Immigration, Nativism & Race in the United States 7 Advancing Civil Justice Access in the 21st Century 7 10 New Reports on the Earnings & Job Outcomes of College Graduates 14 Our Common Purpose in Communities Across the Country Members 53 In Memoriam: Louis W. -

2008-Annual-Report.Pdf

whitehead institute 2008 AnnuAl RepoRt. a year in the life of a scientific community empowered to explore biology’s most fundamental questions for the betterment of human health. whitehead institute 2008 annual report a Preserving the mission, contents facing the future 1 preserving the mission, it’s customary in this space to recount and reflect facing the future on the accomplishments of the year gone by. i’ll certainly do so here—proudly—but in many 5 scientific achievement important ways, 2008 was about positioning the institute for years to come. 15 principal investigators many colleges, universities, and independent 30 whitehead fellows research institutions found themselves in dire fiscal positions at the close of 2008 and entered 34 community evolution 2009 in operational crisis reflective of the global economic environment. hiring freezes and large- 40 honor roll of donors scale workforce reductions have become the norm. although whitehead institute is certainly not 46 financial summary insulated from the impact of the downturn, i am 48 leadership pleased and somewhat humbled to report that the institute remains financially strong and no less 49 sited for science committed to scientific excellence. david page, director over the past two years, we have been engaged in a focused effort to increase efficiency and editor & direCtor reduce our administrative costs, with the explicit goal of ensuring that as much of the institute’s matt fearer revenue as possible directly supports Whitehead research. Our approach, which has resulted in assoCiate editor nicole giese a 10-percent reduction in operational expense, has been carefully considered. every decision offiCe of CommuniCation and PubliC affairs has been evaluated not just for its potential effects on our scientific mission, but also for 617.258.5183 www.whitehead.mit.edu possible consequences to the whitehead community and its unique culture. -

Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A

01/08/2018 Discovery of DNA Double Helix: Watson and Crick | Learn Science at Scitable NUCLEIC ACID STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION | Lead Editor: Bob Moss Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A. Pray, Ph.D. © 2008 Nature Education Citation: Pray, L. (2008) Discovery of DNA structure and function: Watson and Crick. Nature Education 1(1):100 The landmark ideas of Watson and Crick relied heavily on the work of other scientists. What did the duo actually discover? Aa Aa Aa Many people believe that American biologist James Watson and English physicist Francis Crick discovered DNA in the 1950s. In reality, this is not the case. Rather, DNA was first identified in the late 1860s by Swiss chemist Friedrich Miescher. Then, in the decades following Miescher's discovery, other scientists--notably, Phoebus Levene and Erwin Chargaff--carried out a series of research efforts that revealed additional details about the DNA molecule, including its primary chemical components and the ways in which they joined with one another. Without the scientific foundation provided by these pioneers, Watson and Crick may never have reached their groundbreaking conclusion of 1953: that the DNA molecule exists in the form of a three-dimensional double helix. The First Piece of the Puzzle: Miescher Discovers DNA Although few people realize it, 1869 was a landmark year in genetic research, because it was the year in which Swiss physiological chemist Friedrich Miescher first identified what he called "nuclein" inside the nuclei of human white blood cells. (The term "nuclein" was later changed to "nucleic acid" and eventually to "deoxyribonucleic acid," or "DNA.") Miescher's plan was to isolate and characterize not the nuclein (which nobody at that time realized existed) but instead the protein components of leukocytes (white blood cells). -

Nobel Laureates Endorse Joe Biden

Nobel Laureates endorse Joe Biden 81 American Nobel Laureates in Physics, Chemistry, and Medicine have signed this letter to express their support for former Vice President Joe Biden in the 2020 election for President of the United States. At no time in our nation’s history has there been a greater need for our leaders to appreciate the value of science in formulating public policy. During his long record of public service, Joe Biden has consistently demonstrated his willingness to listen to experts, his understanding of the value of international collaboration in research, and his respect for the contribution that immigrants make to the intellectual life of our country. As American citizens and as scientists, we wholeheartedly endorse Joe Biden for President. Name Category Prize Year Peter Agre Chemistry 2003 Sidney Altman Chemistry 1989 Frances H. Arnold Chemistry 2018 Paul Berg Chemistry 1980 Thomas R. Cech Chemistry 1989 Martin Chalfie Chemistry 2008 Elias James Corey Chemistry 1990 Joachim Frank Chemistry 2017 Walter Gilbert Chemistry 1980 John B. Goodenough Chemistry 2019 Alan Heeger Chemistry 2000 Dudley R. Herschbach Chemistry 1986 Roald Hoffmann Chemistry 1981 Brian K. Kobilka Chemistry 2012 Roger D. Kornberg Chemistry 2006 Robert J. Lefkowitz Chemistry 2012 Roderick MacKinnon Chemistry 2003 Paul L. Modrich Chemistry 2015 William E. Moerner Chemistry 2014 Mario J. Molina Chemistry 1995 Richard R. Schrock Chemistry 2005 K. Barry Sharpless Chemistry 2001 Sir James Fraser Stoddart Chemistry 2016 M. Stanley Whittingham Chemistry 2019 James P. Allison Medicine 2018 Richard Axel Medicine 2004 David Baltimore Medicine 1975 J. Michael Bishop Medicine 1989 Elizabeth H. Blackburn Medicine 2009 Michael S. -

Medical Advisory Board September 1, 2006–August 31, 2007

hoWard hughes medical iNstitute 2007 annual report What’s Next h o W ard hughes medical i 4000 oNes Bridge road chevy chase, marylaNd 20815-6789 www.hhmi.org N stitute 2007 a nn ual report What’s Next Letter from the president 2 The primary purpose and objective of the conversation: wiLLiam r. Lummis 6 Howard Hughes Medical Institute shall be the promotion of human knowledge within the CREDITS thiNkiNg field of the basic sciences (principally the field of like medical research and education) and the a scieNtist 8 effective application thereof for the benefit of mankind. Page 1 Page 25 Page 43 Page 50 seeiNg Illustration by Riccardo Vecchio Südhof: Paul Fetters; Fuchs: Janelia Farm lab: © Photography Neurotoxin (Brunger & Chapman): Page 3 Matthew Septimus; SCNT images: by Brad Feinknopf; First level of Rongsheng Jin and Axel Brunger; iN Bruce Weller Blake Porch and Chris Vargas/HHMI lab building: © Photography by Shadlen: Paul Fetters; Mouse Page 6 Page 26 Brad Feinknopf (Tsai): Li-Huei Tsai; Zoghbi: Agapito NeW Illustration by Riccardo Vecchio Arabidopsis: Laboratory of Joanne Page 44 Sanchez/Baylor College 14 Page 8 Chory; Chory: Courtesy of Salk Janelia Farm guest housing: © Jeff Page 51 Ways Illustration by Riccardo Vecchio Institute Goldberg/Esto; Dudman: Matthew Szostak: Mark Wilson; Evans: Fred Page 10 Page 27 Septimus; Lee: Oliver Wien; Greaves/PR Newswire, © HHMI; Mello: Erika Larsen; Hannon: Zack Rosenthal: Paul Fetters; Students: Leonardo: Paul Fetters; Riddiford: Steitz: Harold Shapiro; Lefkowitz: capacity Seckler/AP, © HHMI; Lowe: Zack Paul Fetters; Map: Reprinted by Paul Fetters; Truman: Paul Fetters Stewart Waller/PR Newswire, Seckler/AP, © HHMI permission from Macmillan Page 46 © HHMI for Page 12 Publishers, Ltd.: Nature vol. -

Pomona College Magazine Fall/Winter 2020: the New (Ab

INSIDE:THE NEW COLLEGE MAGAZINE (AB)NORMAL • The Economy • Childcare • City Life • Dating • Education • Movies • Elections Fall-Winter 2020 • Etiquette • Food • Housing •Religion • Sports • Tourism • Transportation • Work & more Nobel Laureate Jennifer Doudna ’85 HOMEPAGE Together in Cyberspace With the College closed for the fall semester and all instruction temporarily online, Pomona faculty have relied on a range of technologies to teach their classes and build community among their students. At top left, Chemistry Professor Jane Liu conducts a Zoom class in Biochemistry from her office in Seaver North. At bottom left, Theatre Professor Giovanni Molina Ortega accompanies students in his Musical Theatre class from a piano in Seaver Theatre. At far right, German Professor Hans Rindesbacher puts a group of beginning German students through their paces from his office in Mason Hall. —Photos by Jeff Hing STRAY THOUGHTS COLLEGE MAGAZINE Pomona Jennifer Doudna ’85 FALL/WINTER 2020 • VOLUME 56, NO. 3 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry The New Abnormal EDITOR/DESIGNER Mark Wood ([email protected]) e’re shaped by the crises of our times—especially those that happen when ASSISTANT EDITOR The Prize Wwe’re young. Looking back on my parents’ lives with the relative wisdom of Robyn Norwood ([email protected]) Jennifer Doudna ’85 shares the 2020 age, I can see the currents that carried them, turning them into the people I knew. Nobel Prize in Chemistry for her work with They were both children of the Great Depression, and the marks of that experi- BOOK EDITOR the CRISPR-Cas9 molecular scissors. Sneha Abraham ([email protected]) ence were stamped into their psyches in ways that seem obvious to me now. -

Dr. David P. Bartel Journal Interviews

Home About Scientific Press Room Contact Us ● ScienceWatch Home ● Interviews Featured Interviews Author Commentaries Institutional Interviews 2008 : June 2008 - Author Commentaries : Dr. David P. Bartel Journal Interviews Podcasts AUTHOR COMMENTARIES - 2008 ● Analyses June 2008 Featured Analyses Dr. David P. Bartel A Featured Scientist from Essential Science IndicatorsSM What's Hot In... Special Topics Earlier this year, ScienceWatch.com published an analysis of high-impact research in Molecular Biology & Genetics over the past five years. The ● Data & Rankings analysis ranked David Bartel #2 among authors publishing high-impact papers in this field, based on 19 papers cited a total of 4,542 times. Sci-Bytes In Essential Science Indicators from Thomson Reuters, Dr. Bartel's record Fast Breaking Papers includes 76 original articles and review papers published between January 1, New Hot Papers 1998 and February 29, 2008, with a total of 10,386 cites. These papers can be found in the fields of Molecular Biology & Genetics, Biology & Emerging Research Fronts Biochemistry, and Plant & Animal Science. Fast Moving Fronts Research Front Maps Current Classics Dr. Bartel is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator whose lab is based at the Whitehead Institute Top Topics for Biomedical Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He is also a Professor in the Department of Biology at MIT. Rising Stars New Entrants In the interview below, he talks with correspondent Gary Taubes about his highly cited research. Country Profiles What motivated your research originally on these small, non-coding RNAs, and particularly the 2000 Cell paper (Zamore PD, et al., RNAi: double-stranded RNA directs the ATP-dependent ● About Science Watch cleavage of mRNA at 21 to 23 nucleotide intervals," 101[1]: 25-33, 31 March 200), which is your most-highly cited paper that’s not a review? Methodology Tom Tuschl and Phil Zamore [see also] were postdocs in my lab working in collaboration with Phil Sharp Archives [see also] on the biochemistry of RNAi. -

World's Leading Scientists and Technologists to Gather at the Global

MEDIA RELEASE WORLD’S LEADING SCIENTISTS AND TECHNOLOGISTS TO GATHER AT THE GLOBAL YOUNG SCIENTISTS SUMMIT 2021 Summit will host 21 eminent scientists including Nobel Laureates, who will engage and share first-hand insights in science and research with over 500 young scientists from 30 countries 6 JANUARY 2021, SINGAPORE – The National Research Foundation Singapore (NRF) will host the ninth edition of the Global Young Scientists Summit (GYSS), which will see the gathering of the world’s foremost scientists and technologists engage and inspire aspiring young scientists. Held virtually from 12 to 15 January 2021, the eminent scientists will also discuss the latest advances in research and how they can be used to develop solutions to address major global challenges. The Summit will be graced by Singapore’s Deputy Prime Minister and Chairman of NRF, Mr Heng Swee Keat, who will deliver the opening address. The GYSS is a multi-disciplinary event covering the disciplines of chemistry, physics, biology, mathematics, computer science, and engineering. During the event, luminary scientists and technologists will share details of their discoveries by delivering plenary addresses, participating in panel discussions, and engaging with the young scientists in small group discussions. They will also provide mentorship to over 500 young researchers from more than 30 countries. Star-studded panel speaking on a wide range of subjects and issues This year, the GYSS sees 21 speakers, the highest number since the start of the Summit, of whom 17 are speaking at the Summit for the first time. The list includes Nobel Laureates, Fields Medallists, Millennium Technology Prize and the Turing Award winners. -

Circadian Rhythm Prof

2 Science Horizon Volume 2 Issue 10 October, 2017 President, Odisha Bigyan Academy Editorial Board Prof. Sanghamitra Mohanty Prof. Rama Shankar Rath Chief Editor Er. Mayadhar Swain Prof. Niranjan Barik Prof. G. B. N. Chainy Editor Dr. Trinath Moharana Prof. Tarani Charan Kara Prof. Madhumita Das Managing Editor Prof. Bijay Kumar Parida Dr. Prafulla Kumar Bhanja Secretary, Odisha Bigyan Academy Dr. Shaileswar Nanda CONTENTS Subject Author Page 1. Editorial : Neuroplasticity - An Overview Prof. Tarani Charan Kara 1 2. Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 2017 Dr. Niraj K. Tripathy 3 3. Circadian Rhythm Prof. G.B.N. Chainy 6 4. Timeline of Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine Abhaya Kumar Dalai 9 5. Loss of Memories "Alzheimer" Prof. (Dr.) Saileswar Nanda 11 6. Health Problems of Elderly Persons Dr. Kalyanee Dash 13 7. Nanomedicine : An Overview Binapani Mahaling 16 Aumreetam Dinabandhu 8. Nutritive Value of Poultry Egg Dr. B. C. Das 21 Dr. K. K. Sardar 9. Human Agenda for Twenty First Century Dr. Soumendra Ghosh 25 10. Protected Cultivation : Scope and Importance Mir Miraj Alli 27 Anwesha Dalbehera 11. The Red Pearl on the Greenery Prof. Animesh K. Mohapatra 32 Saptabarna Mukherjee 12. Artificial Light Pollution : A Problem for All Dr. Tapan Kumar Barik 36 13. Science in Search of Missing Netaji Dr. Nikhilanand Panigrahy 40 14. Galileo Galilei - The Father of Modern Science Prof. Ramsankar Rath 43 15. Detection of Evidence for the Existence of New Planets Dr. Sadasiva Biswal 45 16. Quiz : Computer Science & Information Technology Sri Sai Swaroop Bedamatta 47 The Cover Page depicts : Structure of Brain and Neural Synapsis Cover Design : Sanatan Rout neutron star EDITORIAL NEUROPLASTICITY - AN OVERVIEW Brain, the centre of the nervous system in all are not fixed, but appearing and disappearing vertebrates, is perhaps the most complex of biological dynamically throughout the life. -

Jewels in the Crown

Jewels in the crown CSHL’s 8 Nobel laureates Eight scientists who have worked at Cold Max Delbrück and Salvador Luria Spring Harbor Laboratory over its first 125 years have earned the ultimate Beginning in 1941, two scientists, both refugees of European honor, the Nobel Prize for Physiology fascism, began spending their summers doing research at Cold or Medicine. Some have been full- Spring Harbor. In this idyllic setting, the pair—who had full-time time faculty members; others came appointments elsewhere—explored the deep mystery of genetics to the Lab to do summer research by exploiting the simplicity of tiny viruses called bacteriophages, or a postdoctoral fellowship. Two, or phages, which infect bacteria. Max Delbrück and Salvador who performed experiments at Luria, original protagonists in what came to be called the Phage the Lab as part of the historic Group, were at the center of a movement whose members made Phage Group, later served as seminal discoveries that launched the revolutionary field of mo- Directors. lecular genetics. Their distinctive math- and physics-oriented ap- Peter Tarr proach to biology, partly a reflection of Delbrück’s physics train- ing, was propagated far and wide via the famous Phage Course that Delbrück first taught in 1945. The famous Luria-Delbrück experiment of 1943 showed that genetic mutations occur ran- domly in bacteria, not necessarily in response to selection. The pair also showed that resistance was a heritable trait in the tiny organisms. Delbrück and Luria, along with Alfred Hershey, were awarded a Nobel Prize in 1969 “for their discoveries concerning the replication mechanism and the genetic structure of viruses.” Barbara McClintock Alfred Hershey Today we know that “jumping genes”—transposable elements (TEs)—are littered everywhere, like so much Alfred Hershey first came to Cold Spring Harbor to participate in Phage Group wreckage, in the chromosomes of every organism. -

Fire Departments of Pathology and Genetics, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Room L235, Stanford, CA 94305-5324, USA

GENE SILENCING BY DOUBLE STRANDED RNA Nobel Lecture, December 8, 2006 by Andrew Z. Fire Departments of Pathology and Genetics, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Room L235, Stanford, CA 94305-5324, USA. I would like to thank the Nobel Assembly of the Karolinska Institutet for the opportunity to describe some recent work on RNA-triggered gene silencing. First a few disclaimers, however. Telling the full story of gene silencing would be a mammoth enterprise that would take me many years to write and would take you well into the night to read. So we’ll need to abbreviate the story more than a little. Second (and as you will see) we are only in the dawn of our knowledge; so consider the following to be primer... the best we could do as of December 8th, 2006. And third, please understand that the story that I am telling represents the work of several generations of biologists, chemists, and many shades in between. I’m pleased and proud that work from my labo- ratory has contributed to the field, and that this has led to my being chosen as one of the messengers to relay the story in this forum. At the same time, I hope that there will be no confusion of equating our modest contributions with those of the much grander RNAi enterprise. DOUBLE STRANDED RNA AS A BIOLOGICAL ALARM SIGNAL These disclaimers in hand, the story can now start with a biography of the first main character. Double stranded RNA is probably as old (or almost as old) as life on earth. -

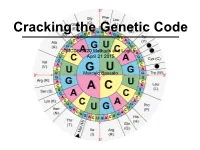

MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo

Cracking the Genetic Code MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) Frederick Griffith The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) Oswald Avery Alfred Hershey Martha Chase The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) Linus Carl Pauling The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) James Watson and Francis Crick The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) How is DNA (4 nucleotides) the genetic material while proteins (20 amino acids) are the building blocks? ? DNA Protein ? The Coding Craze ? DNA Protein What was already known? • DNA resides inside the nucleus - DNA is not the carrier • Protein synthesis occur in the cytoplasm through ribosomes {• Only RNA is associated with ribosomes (no DNA) - rRNA is not the carrier { • Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was a homogeneous population The “messenger RNA” hypothesis François Jacob Jacques Monod The Coding Craze ? DNA RNA Protein RNA Tie Club Table from Wikipedia The Coding Craze Who won the race Marshall Nirenberg J.