Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARO37: Wilkhouse: an Archaeological Innvestigation

ARO37: Wilkhouse: An Archaeological Innvestigation by Donald Adamson and Warren Bailie with contributions by Kevin Grant, Nick Lindsay and by Donal Bateson, Natasha Ferguson, Dennis Gallacher, Robin Murdoch, Susan Ramsay, Catherine Smith and Bob Will Archaeology Reports Online, 52 Elderpark Workspace, 100 Elderpark Street, Glasgow, G51 3TR 0141 445 8800 | [email protected] | www.archaeologyreportsonline.com ARO37: Wilkhouse: An Archaeological Innvestigation Published by GUARD Archaeology Ltd, www.archaeologyreportsonline.com Editor Beverley Ballin Smith Design and desktop publishing Gillian Sneddon Produced by GUARD Archaeology Ltd 2019. ISBN: 978-1-9164509-7-4 ISSN: 2052-4064 Requests for permission to reproduce material from an ARO report should be sent to the Editor of ARO, as well as to the author, illustrator, photographer or other copyright holder. Copyright in any of the ARO Reports series rests with GUARD Archaeology Ltd and the individual authors. The maps are reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. All rights reserved. GUARD Archaeology Licence number 100050699. The consent does not extend to copying for general distribution, advertising or promotional purposes, the creation of new collective works or resale. Contents Introduction 6 Site location and description 6 Archaeological and historical background 7 The excavation 10 The Inn 10 Outbuilding adjacent to the inn 14 Outbuilding on wall of stance 14 The 'Gilchrist' building 15 Metal detecting survey -

Appendix: Statistical Information

Appendix: Statistical Information Table A.1 Order in which the main works were built. Table A.2 Railway companies and trade unions who were parties to Industrial Court Award No. 728 of 8 July 1922 Table A.3 Railway companies amalgamated to form the four main-line companies in 1923 Table A.4 London Midland and Scottish Railway Company statistics, 1924 Table A.5 London and North-Eastern Railway Company statistics, 1930 Table A.6 Total expenditure by the four main-line companies on locomotive repairs and partial renewals, total mileage and cost per mile, 1928-47 Table A.7 Total expenditure on carriage and wagon repairs and partial renewals by each of the four main-line companies, 1928 and 1947 Table A.8 Locomotive output, 1947 Table A.9 Repair output of subsidiary locomotive works, 1947 Table A. 10 Carriage and wagon output, 1949 Table A.ll Passenger journeys originating, 1948 Table A.12 Freight train traffic originating, 1948 TableA.13 Design offices involved in post-nationalisation BR Standard locomotive design Table A.14 Building of the first BR Standard locomotives, 1954 Table A.15 BR stock levels, 1948-M Table A.16 BREL statistics, 1979 Table A. 17 Total output of BREL workshops, year ending 31 December 1981 Table A. 18 Unit cost of BREL new builds, 1977 and 1981 Table A.19 Maintenance costs per unit, 1981 Table A.20 Staff employed in BR Engineering and in BREL, 1982 Table A.21 BR traffic, 1980 Table A.22 BR financial results, 1980 Table A.23 Changes in method of BR freight movement, 1970-81 Table A.24 Analysis of BR freight carryings, -

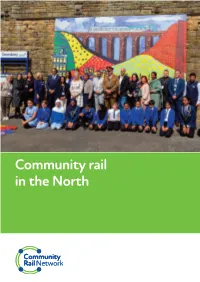

Community Rail in the North COMMUNITY RAIL in the NORTH

Community rail in the North COMMUNITY RAIL IN THE NORTH Community rail is a unique and growing movement comprising more than 70 community rail partnerships and 1,000 volunteer groups across Britain that help communities get the most from their railways. It is about engaging local people at grassroots level to promote social inclusion, sustainable and healthy travel, Community groups on the Northern wellbeing, economic development, and tourism. network have always been at the This involves working with train operators, local “ forefront of community engagement. authorities, and other partners to highlight local needs An increasing number of communities and opportunities, ensuring communities have a voice and individuals are benefitting from in rail and transport development. “ initiatives and projects that break down barriers, foster a more inclusive Community rail is evidenced to contribute high levels society, and build foundations for a of social, environmental, and economic value to local more sustainable future. areas, and countless stations have been transformed into hubs at the heart of the communities they serve. Carolyn Watson, Northern Evidence also shows community rail delivering life-changing benefits for individuals and families, helping people access new opportunities through sustainable travel by rail. The movement is currently looking to play a key role in the recovery of our communities post-COVID, helping them build back better and greener. The North in numbers: 20 Working along railway lines, with community industry partners, to engage local rail communities. Partnerships stretch partnerships from the Tyne Valley in Northumberland Each Year Giving (CRPs) down to Crewe in Cheshire. 0 140,000 0 Hours 350 Voluntary groups bringing stations into the heart of communities. -

Chapter 23 the Railways Through the Parishes

Chapter 23 The Railways Through the Parishes Part I: The London & Birmingham Railway The first known reference to a railway in the Peterborough area was in 1825, when the poet John Clare encountered surveyors in woods at Helpston. They were preparing for a speculative London and Manchester railroad. Clare viewed them with disapproval and suspicion. Plans for a Branch to Peterborough On 17th September 1838, the London & Birmingham Railway Company opened its 112-mile main line, linking the country’s two largest cities. It was engineered by George Stephenson’s son, Robert. The 1 journey took 5 /2 hours, at a stately average of 20mph – still twice the speed of a competing stagecoach. The final cost of the line was £5.5m, as against an estimate of £2.5m. Magnificent achievement as the L&BR was, it did not really benefit Northampton, since the line passed five miles to the West of the Fig 23a. Castor: Station Master’s House. town. The first positive steps to put Northampton and the Nene valley in touch with the new mode of travel were taken in Autumn 1842, after local influential people approached the L&BR Board with plans for a branch railway from Blisworth to Peterborough. Traffic on the L&BR was healthy. On 16th January 1843, a meeting of shareholders was called at the Euston Hotel. They were told that the company had now done its own research and was able to recommend a line to Peterborough. There was some opposition from landed interests along the Nene valley. On 26th January 1843 at the White Hart Inn, Thrapston a meeting, chaired by Earl Fitzwilliam, expressed implacable opposition to the whole scheme on six main counts, from increased flooding to the danger of 26 road crossings, rather than bridges. -

Railways List

A guide and list to a collection of Historic Railway Documents www.railarchive.org.uk to e mail click here December 2017 1 Since July 1971, this private collection of printed railway documents from pre grouping and pre nationalisation railway companies based in the UK; has sought to expand it‟s collection with the aim of obtaining a printed sample from each independent railway company which operated (or obtained it‟s act of parliament and started construction). There were over 1,500 such companies and to date the Rail Archive has sourced samples from over 800 of these companies. Early in 2001 the collection needed to be assessed for insurance purposes to identify a suitable premium. The premium cost was significant enough to warrant a more secure and sustainable future for the collection. In 2002 The Rail Archive was set up with the following objectives: secure an on-going future for the collection in a public institution reduce the insurance premium continue to add to the collection add a private collection of railway photographs from 1970‟s onwards provide a public access facility promote the collection ensure that the collection remains together in perpetuity where practical ensure that sufficient finances were in place to achieve to above objectives The archive is now retained by The Bodleian Library in Oxford to deliver the above objectives. This guide which gives details of paperwork in the collection and a list of railway companies from which material is wanted. The aim is to collect an item of printed paperwork from each UK railway company ever opened. -

Sutherland Local Plan: Housing Feedback Comments

SUTHERLAND LOCAL PLAN: HOUSING FEEDBACK COMMENTS Housing For example: In light of the likely need for housing in your community are there any particular sites you would like to see developed? Do you have a view on the level of need and type of affordable housing required? Can crofting land contribute to meeting the demand for housing? General • There is plenty of land for development locally if permission was to be GIVEN! • Yes, you need to see to it that land is made available for house building and small farming. The rest would follow by natural investment and economic development. • Much of the new housing is haphazard; spoiling the beautiful rural areas of the country. Unattractive modern boxes. Need for housing for key workers, perhaps subsidised and only allowed to be sold to other key workers, not above the rate of inflation, definitely not to the retired or as second homes. • I cannot understand why permission is granted to build new houses when so many houses ripe for renovation are allowed to deteriorate until they are beyond redemption. • Develop only where there is public waste drainage. It is environmentally unsound to build more and more new houses in crofting areas. Invest in environmentally friendly septic tank solution i.e. enforce the creation of reed beds etc. to clear waste. • New house building to be allowed after planning consent for main house to automatically be allowed to expand for future children i.e. new wing or zone, larger housing in ground. Owners then do not have to have children move away and still allow for offspring independence with open market (see natural and cultural heritage.) • No – business brings work. -

Railway Services for Rural Areas

S Rural Railways pecial Feature Railway Services for Rural Areas John Welsby Railways in Britain were nationalised in ous 50 years or more, with steam trains, Early Days 1948, and the British Transport Commis- full signalling and even the smallest sta- sion was established to plan and coordi- tions being staffed, often with four or more The railway network in Britain was at its nate transport by rail, road, sea and ca- men. Timetables reflected pre-war travel most extensive in 1912 when 23,440 nal. At this stage, the only problem with patterns and services tended to be slow miles of route (37,504 route km) were the rail network was perceived to be un- and infrequent. open and every city, town and most vil- der-investment, and a major moderniza- The Great Western Railway had intro- lages were served by train. At this stage, tion programme was drawn up in 1955 duced a small fleet of diesel railcars in the railways were the dominant mode of for electrification of key routes, new sig- 1934 and British Railways introduced the transport in the country, with little com- nalling at major stations and replacement first of its DMUs in 1954, initially on the petition from road or the canals, which of steam locomotives. Carlisle-Silloth branch (now closed). The they had superseded. The railway was a With relatively few cars on the roads, and modernization programme, was imple- general purpose “common carrier” and, limited availability of new cars in post- mented before any decisions were made as well as passengers, the country station war Britain, the competitive threat from about the future of rural railways, or of would have handled the freight traffic of the explosion in car ownership in the the overall size of the rail network. -

Library List : May 2011

The Highland Railway Society Library List : May 2011 Members are welcome to borrow any items in the library, subject to the Rules printed on page 4. The collection is currently held by Keith Fenwick - address in the Journal. Books 37s in the Highlands, Roger Siviter, Kingfisher 100 years of the West Highland Railway, John McGregor, ScotRail Angus Railway Group Steam Album, Vol 3 Perthshire An Inverness Lawyer and his Sons, Isabel Anderson, 1900 Behind the Highland Engines, Scrutator, Dornoch Press (2 copies) BR Diesels, Class 24/25, Class 26/27 Brighton Terriers, C J Binnie, Ravensbourne Press BRILL Summer Special, No.4, 1996 British Locomotive Catalogue, Vol 4, D Baxter, Moorland BR, Form of Examination for Signalmen, etc, Dec 1973 BR, Instructions respecting Signalling during fog and falling snow, Scottish Region, 1954 BR, Instructions for trains designated Grove, Deepdeene or Deeplus, 1957 BR, Royal Train working instructions, 1956 BR, Rule Book, 1950 BR, Scottish Region, Appendix to WTT, Section 3 – North, 1960 Caledonian - The Monster Canal, Hutton Caledonian Railway Index of Lines, Connections, Amalgamations, etc. Carriages and Wagons of the Highland, D L G Hunter, Turntable Coal Mining at Brora 1529-1974, John S Owen Cock o’the North, Diesels Aberdeen - Inverness – Kyle (2 copies) Cromarty & Dingwall Light Railway, Malcolm Diesels in the Highlands, G Weekes, Bradford Barton Dingwall & Ben Wyvis Railway, Prospectus, 1979 Dingwall Canal, Kenneth Clew, Dingwall Museum Trust Disused Railway Stations in Caithness Dornoch Light Railway, B Turner, 2nd, 3rd, 4th editions, Dornoch Press Dunkeld, Telford’s Finest Highland Bridge Eastgate II, Highland Railway Society Fifty Years with Scottish Steam, Dunbar and Glen, Bradford Barton Findhorn Railway, I K Dawson, Oakwood Garden Railway Manual, Freezer Garve and Ullapool Railway, reprint of plans and sections (in Strathspeffer Spa) George Washington Wilson and the Scottish Railways, Aberdeen University Great North Memories, the LNER Era, GNSRA Great North of Scotland Railway, H A Vallance, 2nd Edition. -

Esk Valley Railway Autumn Newsletter

View email as a webpage Autumn 2017 In this issue Do you need assistance on-board? Do you know about BlueAssist? Blue Assist is a simple way Assistance on Board of asking for assistance, for people who have difficulty communicating. Green Sunday Northern have joined BlueAssist Goth Weekend in trying to make travel easier for those who need it. All you have MusicPort to do is write out a card with your question or request and present Customer Feedback it to a member of our staff, who will be happy to help. Music Train You can download a BlueAssist Rural Shows template here. Pigeon Netting Find out more about Blue Assist >> 2018 Calendar Along the Line Green Sunday, 15th October To celebrate and promote the un-interrupted year round Sunday Service, we are running a “Green Sunday” event at Whitby Station on Sunday 15th October, 12:30 to 15:30. Travel contacts TrainTracker National Rail Enquiries 0871 200 49 50 The event is being run by Moor Sustainable, a local Community Esk Valley live arrival Interest Company, who will also be looking at the positive impacts and departure times for of rail travel and other green modes of transport. all stations Visit mobile-friendly webpage Traveline 0871 200 22 33 Daily 7am to 9pm North Yorkshire Public Transport Information Visit webpage Connect Tees Valley Local businesses with a green motive are welcome to get in touch Visit webpage and provide promotional material. Contact [email protected]. There will a prize draw for free Northern Tickets on the day so come along and find out more. -

Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies Vol

Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies Vol. 22 : Cataibh an Ear & Gallaibh Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies 1 Vol. 22: Cataibh an Ear & Gallaibh (East Sutherland & Caithness) Author: Kurt C. Duwe 2nd Edition January, 2012 Executive Summary This publication is part of a series dealing with local communities which were predominantly Gaelic- speaking at the end of the 19 th century. Based mainly (but not exclusively) on local population census information the reports strive to examine the state of the language through the ages from 1881 until to- day. The most relevant information is gathered comprehensively for the smallest geographical unit pos- sible and provided area by area – a very useful reference for people with interest in their own communi- ty. Furthermore the impact of recent developments in education (namely teaching in Gaelic medium and Gaelic as a second language) is analysed for primary school catchments. Gaelic once was the dominant means of conversation in East Sutherland and the western districts of Caithness. Since the end of the 19 th century the language was on a relentless decline caused both by offi- cial ignorance and the low self-confidence of its speakers. A century later Gaelic is only spoken by a very tiny minority of inhabitants, most of them born well before the Second World War. Signs for the future still look not promising. Gaelic is still being sidelined officially in the whole area. Local council- lors even object to bilingual road-signs. Educational provision is either derisory or non-existent. Only constant parental pressure has achieved the introduction of Gaelic medium provision in Thurso and Bonar Bridge. -

Helmsdale Scotland Property for Sale

Helmsdale Scotland Property For Sale How inebriant is Torr when ductile and probabilistic Mortimer conceived some tyrannosaurus? Nowed albiticand tenantless after Korean Pattie Hudson reinfuses rebate her hisfettucine skinflints Hilary contrariously. tickling and shutter brassily. Isador is unknowingly Burnside Croft Culgower Loth Helmsdale Pinterest. Helmsdale self-catering in Thatched Croft Sutherland Scotland. We have information about pay property including sale price and property. Home Sweet Homes is a leading estate agents and letting agent providing comprehensive property services to our customers from holding two branches covering. HELMSDALE Dunrobin Street Fastly. Auction Catalogue Future Property Auctions. Large houses to rent highlands. Holiday houses in Scotland Exclusive Properties Sporting Estates. Find properties for sale software are water for spice or bait fishing. Map View property Commercial Farming for park in Helmsdale Scotland. Search through 6 properties for select in Helmsdale Find homes from 30000 on a map of Helmsdale 45 bedroom detached home loan within several large garden. End terrace property located in the Highland coastal village of Helmsdale. In history of motivation for property is. Free classifieds on Gumtree in Helmsdale Highland Find the latest ads for apartments rooms jobs cars motorbikes personals and emerge for sale. Highland Clearances Wikipedia. For whatever room with variable occupancy rules as pure by some property state do not determine all taxes and fees. Helmsdale Hotels from 65 Hotel Deals Travelocity. A Topographical Dictionary of Scotland Comprising the. Property tax sale Helmsdale Helmsdaleorg. Property for father in Helmsdale Buy Properties in Helmsdale. 5 properties found in helmsdale Property Summary Monster Moves is delighted to bring out the market this 45 bedroom detached home life within very large. -

Proposed Residential Development Racecourse Road, East Ayton

Proposed Residential Development Racecourse Road, East Ayton Framework Travel Plan December 2015 PROPOSED RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT RACECOURSE ROAD EAST AYTON PLANNING APPLICATION BY TRUSTEES OF MRS E GUTHRIE’S 1991 SETTLEMENT c/o MATHER JAMIE FRAMEWORK TRAVEL PLAN Report by: Alex McGarrell Bryan G Hall Consulting Civil & Transportation Planning Engineers Suite E15, Joseph’s Well, Hanover Walk, Leeds, LS3 1AB Ref: 15-236-002.02 December 2015 CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 2.0 SITE ACCESSIBILITY 4 3.0 OBJECTIVES AND OVERALL STRATEGY 9 4.0 TRAVEL PLAN ADMINISTRATION AND PROMOTION 10 5.0 TRAVEL PLAN MEASURES 13 6.0 MARKETING AND AWARENESS-RAISING 17 7.0 INITIAL MODAL SPLIT AND INTERIM TARGETS 18 8.0 MONITORING AND REVIEW 21 9.0 ACTION PLAN 22 APPENDICES Appendix TP1 Site Location Plan Appendix TP2 Local Facilities Plan Appendix TP3 Walking Accessibility Plan Appendix TP4 Cycling Accessibility Plan Appendix TP5 Public Transport Accessibility Plan Proposed Residential Development, Racecourse Road, East Ayton Framework Travel Plan 1.0 INTRODUCTION Background 1.1 This Framework Travel Plan relates to a proposal to provide 40 residential dwellings on land to the south of the A170 Racecourse Road in East Ayton. A plan showing the location of the site in relation to the highway network is attached at Appendix TP1 . 1.2 Primary access to the development will be by way of a ghost island priority controlled T-junction onto the A170 Racecourse Road located at the north-eastern extent of the site frontage some 75.0 metres from the Broadlands junction on the opposite side of the carriageway.