Sociolinguistic Approaches for Intercultural New Media Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

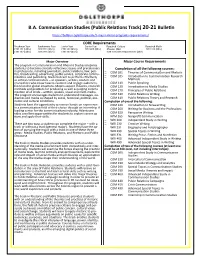

B.A. Communication Studies (Public Relations Track) 20-21 Bulletin

B.A. Communication Studies (Public Relations Track) 20-21 Bulletin https://bulletin.oglethorpe.edu/9-major-minor-programs-requirements/ CORE Requirements Freshman Year Sophomore Year Junior Year Senior Year Required Culture Required Math COR 101 ( 4hrs) COR 201 ( 4hrs) COR 301 (4hrs) COR 400 (4hrs) Choose One: COR 314 (4hrs) COR 102 ( 4hrs) COR 202 ( 4hrs) COR 302 (4hrs) COR 103/COR 104/COR 105 (4hrs) Major Overview Major Course Requirements The program in Communication and Rhetoric Studies prepares students to become critically reflective citizens and practitioners Completion of all the following courses: in professions, including journalism, public relations, law, poli- COM 101 Theories of Communication and Rhetoric tics, broadcasting, advertising, public service, corporate commu- nications and publishing. Students learn to perform effectively COM 105 Introduction to Communication Research as ethical communicators – as speakers, writers, readers and Methods researchers who know how to examine and engage audiences, COM 110 Public Speaking from local to global situations. Majors acquire theories, research COM 120 Introduction to Media Studies methods and practices for producing as well as judging commu- COM 270 Principles of Public Relations nication of all kinds – written, spoken, visual and multi-media. The program encourages students to understand messages, au- COM 310 Public Relations Writing diences and media as shaped by social, historical, political, eco- COM 410 Public Relations Theory and Research nomic and cultural conditions. Completion of one of the following: Students have the opportunity to receive hands-on experience COM 240 Introduction to Newswriting in a communication field of their choice through an internship. A COM 260 Writing for Business and the Professions leading center for the communications industry, Atlanta pro- vides excellent opportunities for students to explore career op- COM 320 Persuasive Writing tions and apply their skills. -

Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 12-2008 Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research Jefferson Pooley Muhlenberg College Elihu Katz University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Pooley, J., & Katz, E. (2008). Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research. Journal of Communication, 58 (4), 767-786. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00413.x This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/269 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research Abstract Communication research seems to be flourishing, as vidente in the number of universities offering degrees in communication, number of students enrolled, number of journals, and so on. The field is interdisciplinary and embraces various combinations of former schools of journalism, schools of speech (Midwest for ‘‘rhetoric’’), and programs in sociology and political science. The field is linked to law, to schools of business and health, to cinema studies, and, increasingly, to humanistically oriented programs of so-called cultural studies. All this, in spite of having been prematurely pronounced dead, or bankrupt, by some of its founders. Sociologists once occupied a prominent place in the study of communication— both in pioneering departments of sociology and as founding members of the interdisciplinary teams that constituted departments and schools of communication. In the intervening years, we daresay that media research has attracted rather little attention in mainstream sociology and, as for departments of communication, a generation of scholars brought up on interdisciplinarity has lost touch with the disciplines from which their teachers were recruited. -

Features of Media Multitasking Experiences

WP2 MEDIA MULTITASKING D2.3.3.6 FEATURES OF MEDIA MULTITASKING EXPERIENCES Media Multitasking D2.3.3.6 Features of media multitasking experience s Authors: Maria Viitanen, Stina Westman, Teemu Kinnunen, Pirkko Oittinen Confidentiality: Consortium Date and status: August 31st , 2012, version 0.1 This work was supported by TEKES as part of the next Media programme of TIVIT (Finnish Strategic Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation in the field of ICT) Next Media - a Tivit Programme Phase 3 (1.1.–31.12.2012) Version history: Version Date State Author(s) OR Remarks (draft/ /update/ final) Editor/Contributors 0.1 31 st August MV, SW, TK, PO Review version {Participants = all research organisations and companies involved in the making of the deliverable} Participants Name Organisation Maria Viitanen Aalto University Researchers Stina Westman Department of Media Teemu Kinnunen Technology Pirkko Oittinen next Media www.nextmedia.fi www.tivit.fi WP2 MEDIA MULTITASKING D2.3.3.6 FEATURES OF MEDIA MULTITASKING EXPERIENCES 1 (40) Next Media - a Tivit Programme Phase 3 (1.1.–31.12.2012) Executive Summary Media multitasking is gaining attention as a phenomenon affecting media consumption especially among younger generations. From both social and technical viewpoints it is an important shift in media use, affecting and providing opportunities for content providers, system designers and advertisers alike. Media multitasking may be divided into media multitasking which refers to using several media together and multitasking with media, which consists of combining non- media activities with media use. In this deliverable we review research on multitasking from various disciplines: cognitive psychology, education, human-computer interaction, information science, marketing, media and communication studies, and organizational studies. -

Communication Studies (COMM) 1 Communication Studies (COMM)

Communication Studies (COMM) 1 Communication Studies (COMM) Search COMM Courses using FocusSearch (http:// COMM 1131. Sex, Relationships, and Communication. (4 Hours) catalog.northeastern.edu/class-search/?subject=COMM) Focuses on communication within the context of close relationships. Topics covered include the role of communication in interpersonal COMM 1000. Communication Studies at Northeastern. (1 Hour) attraction, relationship development, relationship maintenance, and Designed to provide a unique opportunity to engage faculty, professional relationship dissolution. Examines how communication impacts staff, and peer mentors in small group discussions. Introduces students relationship quality and commitment. Offers students an opportunity to to the College of Arts, Media and Design. Offers students an opportunity apply what they learn in the course to their personal and professional to learn about the communication studies major and to explore the lives. different areas of emphasis offered by the department. As part of the course, students are expected to prepare a detailed plan of study and are Attribute(s): NUpath Societies/Institutions introduced to the co-op program and meet their academic co-op advisor. COMM 1210. Persuasion and Rhetoric. (4 Hours) Seeks to teach students to be more astute receivers and producers of COMM 1101. Introduction to Communication Studies. (4 Hours) persuasive messages by learning how to dissect them. Examines both Surveys the field of communication studies. Covers major theories classical and contemporary theories of persuasion, after which students and methodological approaches in communication studies and consider “persuasion in action”—how persuasion is used in everyday situates communication within larger social, political, and economic language, nonverbal communication, sales techniques, politics, and institutions. -

Media Studies and Production Diploam Program Guide

Media Studies and Production Diploma - 31 credits Program Area: Media Studies (Fall 2019) ***REMEMBER TO REGISTER EARLY*** Program Description Required Courses This program is designed to Course Course Title Credits Term prepare the graduate for a wide MCOM 1400* Intro to Mass 3 Communication variety of positions in media MCOM 1420* Digital Video 3 production. Graduates are trained Production for jobs ranging from highly visible MCOM 1422* Audio for the Media 3 on-the-air assignments to positions ENGL 1106* College Composition I 3 on production or news teams. MCOM 1424 Digital Video Editing 3 Graduates can also gain skills MCOM 1426 Project/Production 3 needed for careers in multimedia, Management DVD authoring, film style MCOM 1428* Interactive Media 3 production, and media project & Production MCOM 1795* Portfolio Production 1 production management. Lake MCOM 1797* Media Studies 3 Superior College media studies Internship students receive valuable hands- Electives 6 on experience in LSC’s own audio (refer to Table 1) and video studios, as well as Total credits 31 through internships and *Requires a prerequisite or instructor’s consent experiences at local broadcast stations and media agencies. Program Outcomes Upon graduation, students will be able to: • Shoot and edit single camera media productions using both analog and digital equipment. • Participate in cooperative media production teams. • Voice, record, edit, and produce audio projects, promotions, and commercials using both analog and digital equipment. • Use terms and techniques common to media production and process. Pre-program Requirements Successful entry into this program requires a specific level of skill in the areas of English, mathematics, and reading. -

Journalism, Advertising, and Media Studies (JAMS)

Journalism, Advertising, and Media Studies Interested in This Major? Current Students: Visit us in Bolton Hall, Room 510B, call us at 414-229-4436 or email [email protected] Not a UWM Student yet? Call our Admissions Counselor at 414-229-7711 or email [email protected] Web: uwm.edu/journalism-advertising-media-studies JAMS at UWM Career Opportunities Media has never been more dynamic. The worlds JAMS students have a wide range of career paths open of journalism, advertising, public relations and film to them. Many seek careers in media, marketing, and are changing and growing at a rapid pace, and the communication. Others go on to pursue graduate work in the Department of Journalism, Advertising, and Media social sciences, humanities, and law. Studies (JAMS) is a great place to learn about them. Our alumni can be found in many prestigious organizations: Whether students see themselves working in news, entertainment, social media, advertising, public • Groupon • SC Johnson relations, or are fascinated by media, JAMS courses • Boston Globe • Milwaukee Brewers enable students to customize their education and • Milwaukee Journal • A.V. Club (Onion, Inc.) prepare for their chosen careers. Sentinel • WI Air National Guard Students choose courses to gain a broad • TMJ4 • United Nations understanding of the media’s place in society and • Foley & Lardner University culture, but also concentrate more closely in one of • Vice News • Boys & Girls Clubs of three areas: • WI State Legislature Greater Milwaukee Journalism. The Journalism concentration emphasizes • Bader Rutter writing, information gathering, critical thinking • New England Journal and technology skills in courses taught by media of Medicine • HSA Bank professionals. -

Macro-Sociolinguistics Page 1 MACRO SOCIOLINGUISTICS

MACRO SOCIOLINGUISTICS: INSIGHT LANGUAGE Rohib Adrianto Sangia Abstract: Language can be studied internally and externally. As externally, Sociolinguistics as the branch of linguistics looked or put position in relation to language speakers in the community, because in human society is no longer as individuals, will remain as a social community. Sociolinguistics concerns with two aspects of civilization, language and society, there are appropriate terms which are micro and macro in sociolinguistics. The main differences of them are micro-sociolinguistics or sociolinguistics –in narrow sense- is the study of language in relation to society, while macro-sociolinguistics or the sociology of language is the study of society in relation to language. Macro-sociolinguistics focuses such as social factors, exactly the interaction between language and dialect, the study of the decline and stabilization of minority languages, bilingualism developmental stability in a particular group. Keywords: Language, Sociolinguistics, Macro Sociolinguistics, Bilingualism. INTRODUCTION Language is a communication tool that people use to interact with each other. By mastering the language of humans can know the content of the world through science and new knowledge and had never imagined before. As a means of communication and interaction that is only possessed by humans, language can be studied internally and externally (Thomason and Kaufman, 1988: 22). Internally means the study made against internal elements such as language course, the structure of phonological, morphological, and syntactical alone. While externally meaningful study was conducted to things or factors outside the language, but in the use of language itself, speech community or the environment. Language may refer to the specific capacity in humans to obtain and use a complex system of communication, or to a specific agency of a complex communication system. -

D4d78cb0277361f5ccf9036396b

critical terms for media studies CRITICAL TERMS FOR MEDIA STUDIES Edited by w.j.t. mitchell and mark b.n. hansen the university of chicago press Chicago and London The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2010 Printed in the United States of America 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 1 2 3 4 5 isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 53254- 7 (cloth) isbn- 10: 0- 226- 53254- 2 (cloth) isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 53255- 4 (paper) isbn- 10: 0- 226- 53255- 0 (paper) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Critical terms for media studies / edited by W. J. T. Mitchell and Mark Hansen. p. cm. Includes index. isbn-13: 978-0-226-53254-7 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-226-53254-2 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-13: 978-0-226-53255-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-226-53255-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Literature and technology. 2. Art and technology. 3. Technology— Philosophy. 4. Digital media. 5. Mass media. 6. Image (Philosophy). I. Mitchell, W. J. T. (William John Th omas), 1942– II. Hansen, Mark B. N. (Mark Boris Nicola), 1965– pn56.t37c75 2010 302.23—dc22 2009030841 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48- 1992. Contents Introduction * W. J. T. Mitchell and Mark B. N. Hansen vii aesthetics Art * Johanna Drucker 3 Body * Bernadette Wegenstein 19 Image * W. -

MDST) Is a Distinct Track Within the Umbrella Phd in Media Research and Practice (MDRP)

Ph.D. in Media Studies I. Program Overview The PhD in Media Studies (MDST) is a distinct track within the umbrella PhD in Media Research and Practice (MDRP). Drawing largely from contemporary cultural and critical theory, the Media Studies PhD program focuses on interactions among the major components of modern communication — media institutions, their contents and messages, and their audiences or publics — as a process by which cultural meaning is generated. It examines that process on an interdisciplinary basis through social, economic, political, historical, legal/policy/regulatory and international perspectives, with a strong emphasis on issues involving new communication technology and policy. Students graduate from the program with broad knowledge of the intellectual history of media studies as an important interdisciplinary field of research—its origins; its perennial questions and controversies; its evolution in response to technological, political, economic and cultural change; the full range of methods it employs, both humanistic and social scientific – and a demonstrated capacity to design and execute original and socially significant research about media and their historical and contemporary power and importance. The program strives to produce graduates who demonstrate intellectual leadership, nationally and internationally, in the area(s) of research specialization they choose and/or pioneer, and an interest in and aptitude for generating public awareness and conversation about their scholarship. An important part of doctoral -

COMMUNICATION STUDIES 20223: Communication Theory TR 11:00-12:20 AM, Moudy South 320, Class #70959

This copy of Andrew Ledbetter’s syllabus for Communication Theory is posted on www.afirstlook.com, the resource website for A First Look at Communication Theory, for which he is one of the co-authors. COMMUNICATION STUDIES 20223: Communication Theory TR 11:00-12:20 AM, Moudy South 320, Class #70959 Syllabus Addendum, Fall Semester 2014 Instructor: Dr. Andrew Ledbetter Office: Moudy South 355 Office Phone: 817-257-4524 (terrible way to reach me) E-mail: [email protected] (best way to reach me) Twitter: @dr_ledbetter (also a good way to reach me more publicly) IM screen name (GoogleTalk): DrAndrewLedbetter (this works too) Office Hours: TR 10:00-10:50 AM & 12:30 PM-2:00 PM; W 11:00 AM-12:00 PM (but check with me first); other times by appointment. When possible, please e-mail me in advance of your desired meeting time. Course Text: Em Griffin, Andrew Ledbetter, & Glenn Sparks (2015), A First Look at Communication Theory (9th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. Course Description From TCU’s course catalog: Applies communication theory and practice to a broad range of communication phenomena in intrapersonal, interpersonal and public communication settings. You are about to embark on an exciting adventure through the world of communication theory. In some sense, you already inhabit this “world”—you communicate every day, and you may even be very good at it. But, if you’re like me, sometimes you might find yourself wondering: Why did she say that? Why did I say that in response? What there something that I could have said that would have been better? How could I communicate better with my friends? My parents? At school? At work? If you’ve ever asked any of these questions—and it would be hard for me to believe that there is anyone who hasn’t!—then this course is for you! By the end of our time together, I hope you will come to a deeper, fuller understanding of the power and mystery of human communication. -

Critical Communication History

International Journal of Communication 7 (2013), 1912–1919 1932–8036/20130005 Looking Back, Moving Forward: Critical Communication History Editorial Introduction D. TRAVERS SCOTT Clemson University DEVON POWERS Drexel University In May 2012, the Communication History Interest Group sponsored a preconference at the International Communication Association (ICA) gathering in Phoenix, Arizona. That preconference, entitled Historiography as Intervention, was an effort to extend the flourishing interest in the history of our field by bringing together scholars whose work raised provocative questions pertaining to historical methods and subjects. As the preconference’s organizers, we have collected representative essays delivered that day, with a few additions, in an attempt to ensure that the most useful conversations of that session remain lively in its aftermath. In a way, this section presents a record of the preconference’s history, but it also attempts to point to fruitful directions forward for historical research in our field. We believe it is an auspicious and fitting time for this work, especially given that, less than a year after that ICA preconference, Communication History became an official ICA Division. The title of this special section, “Critical Communication History,” is meant to underscore the agency we ascribe to the scholarship featured here. These contributions are bound together by a common drive to use history to re-envision the purpose, scope, and destiny of the history of communication as a subfield of study. Our field has reached a crucial moment of resolution—one we might even consider calling a “historiographic turn.” As such, communication historians have a new, expanded role to play in establishing a shared past that is not only able to stitch the diverse facets of communication more decidedly together with one another, but also elastic enough to accommodate the range of approaches, subject areas, and questions that have made communication such a rich and vital discipline. -

Choosing Between Communication Studies and Film Studies

Choosing Between Communication Studies and Film Studies Many students with an interest in media arts come to UNCW. They often struggle with whether to major in Communication Studies (COM) or Film Studies (FST). This brief position statement is designed to help in that decision. Common Ground Both programs have at least three things in common. First, they share a common set of technologies and software. Both shoot projects in digital video. Both use Adobe Creative Suite for manipulation of digital images, in particular, Adobe Premiere for video editing. Second, they both address the genre of documentaries. Documentaries blend the interests of both “news” and “narrative” in compelling ways and consequently are of interest to both departments. Finally, both departments are “studies” departments: Communication Studies and Film Studies. Those labels indicate that issues such as history, criticism and theories matter and form the context for the study of any particular skills. Neither department is attempting to compete with Full Sail or other technical training institutes. Critical thinking and application of theory to practice are critical to success in FST and COM. Communication Studies The primary purposes for the majority of video projects are to inform and persuade. Creativity and artistry are encouraged within a wide variety of client- centered and audience-centered production genres. With rare exception, projects are approached with the goal of local or regional broadcast. Many projects are service learning oriented such as creating productions for area non-profit organizations. Students will create public service announcements (PSA), news and sports programming, interview and entertainment prog- rams, training videos, short form documentaries and informational and promotional videos.