Communication and Media Studies, History to 1968

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communication & Implementation for Social Change

Communication & Implementation for Social Change: Mobilizing knowledge across geographic and academic borders Krystle van Hoof Communication for Development One-year master 15 Credits Spring/2016 Supervisor: Helen Hambly Odame ABSTRACT In many academic disciplines, there are promising discoveries and valuable information, which have the potential to improve lives but have not been transferred to or taken up in ‘real world’ practice. There are multiple, complex reasons for this divide between theory and practice—sometimes referred to as the ‘know-do’ gap— and there are a number of disciplines and research fields that have grown out of the perceived need to close these gaps. In the field of health, Knowledge Translation (KT) and its related research field, Implementation Science (IS) aim to shorten the time between discovery and implementation to save and improve lives. In the field of humanitarian development, the discipline of Communication for Development (ComDev) arose from a belief that communication methods could help close the perceived gap in development between high- and low-income societies. While Implementation Science and Communication for Development share some historical roots and key characteristics and IS is being increasingly applied in development contexts, there has been limited knowledge exchange between these fields. The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of the characteristics of IS and ComDev, analyze some key similarities and differences between them and discuss how knowledge from each could help inform the other to more effectively achieve their common goals. Keywords: Communication for development and social change, Diffusion of Innovations, Implementation Science, Knowledge Translation 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. -

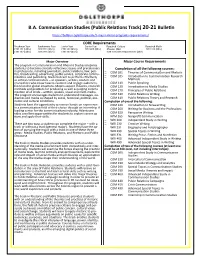

B.A. Communication Studies (Public Relations Track) 20-21 Bulletin

B.A. Communication Studies (Public Relations Track) 20-21 Bulletin https://bulletin.oglethorpe.edu/9-major-minor-programs-requirements/ CORE Requirements Freshman Year Sophomore Year Junior Year Senior Year Required Culture Required Math COR 101 ( 4hrs) COR 201 ( 4hrs) COR 301 (4hrs) COR 400 (4hrs) Choose One: COR 314 (4hrs) COR 102 ( 4hrs) COR 202 ( 4hrs) COR 302 (4hrs) COR 103/COR 104/COR 105 (4hrs) Major Overview Major Course Requirements The program in Communication and Rhetoric Studies prepares students to become critically reflective citizens and practitioners Completion of all the following courses: in professions, including journalism, public relations, law, poli- COM 101 Theories of Communication and Rhetoric tics, broadcasting, advertising, public service, corporate commu- nications and publishing. Students learn to perform effectively COM 105 Introduction to Communication Research as ethical communicators – as speakers, writers, readers and Methods researchers who know how to examine and engage audiences, COM 110 Public Speaking from local to global situations. Majors acquire theories, research COM 120 Introduction to Media Studies methods and practices for producing as well as judging commu- COM 270 Principles of Public Relations nication of all kinds – written, spoken, visual and multi-media. The program encourages students to understand messages, au- COM 310 Public Relations Writing diences and media as shaped by social, historical, political, eco- COM 410 Public Relations Theory and Research nomic and cultural conditions. Completion of one of the following: Students have the opportunity to receive hands-on experience COM 240 Introduction to Newswriting in a communication field of their choice through an internship. A COM 260 Writing for Business and the Professions leading center for the communications industry, Atlanta pro- vides excellent opportunities for students to explore career op- COM 320 Persuasive Writing tions and apply their skills. -

Rhetoric and Media Studies 1

Rhetoric and Media Studies 1 cocurricular activity; credit is available to qualified students through the RHETORIC AND MEDIA practicum program. STUDIES Facilities Radio. Located in Templeton Campus Center, KLC Radio includes two fully Chair: Mitch Reyes equipped stereo studios, a newsroom, and offices. The station webcasts Administrative Coordinator: TBD on and off-campus. From its humanistic roots in ancient Greece to current investigations of the impact of digital technology, rhetoric and media studies is both one of Video. Lewis & Clark’s video production facility includes digital editing the oldest and one of the newest disciplines. Our department addresses capabilities, computer graphics, portable cameras and recording contemporary concerns about how we use messages (both verbal and equipment, and a multiple-camera production studio. Additional video visual) to construct meaning and coordinate action in various domains, recording systems are available on campus. including the processes of persuasion in politics and civic life, the effects of media on beliefs and behavior, the power of film and image to frame The Major Program reality, and the development of identities and relationships in everyday The major in rhetoric and media studies combines core requirements life. While these processes touch us daily and are part of every human with the flexibility of electives. Required courses involve an introductory interaction, no other discipline takes messages and their consequences overview to the field, a course on the design of media or interpersonal as its unique focus. messages, core courses on the theories and methods of rhetoric and media studies, and satisfactory completion of a capstone course. The Department of Rhetoric and Media Studies offers a challenging and Elective courses enable students to explore theory and practice in a wide integrated study of theory and practice. -

Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 12-2008 Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research Jefferson Pooley Muhlenberg College Elihu Katz University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Pooley, J., & Katz, E. (2008). Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research. Journal of Communication, 58 (4), 767-786. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00413.x This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/269 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research Abstract Communication research seems to be flourishing, as vidente in the number of universities offering degrees in communication, number of students enrolled, number of journals, and so on. The field is interdisciplinary and embraces various combinations of former schools of journalism, schools of speech (Midwest for ‘‘rhetoric’’), and programs in sociology and political science. The field is linked to law, to schools of business and health, to cinema studies, and, increasingly, to humanistically oriented programs of so-called cultural studies. All this, in spite of having been prematurely pronounced dead, or bankrupt, by some of its founders. Sociologists once occupied a prominent place in the study of communication— both in pioneering departments of sociology and as founding members of the interdisciplinary teams that constituted departments and schools of communication. In the intervening years, we daresay that media research has attracted rather little attention in mainstream sociology and, as for departments of communication, a generation of scholars brought up on interdisciplinarity has lost touch with the disciplines from which their teachers were recruited. -

HISTORYOF COMMUNICATION in MALAYSIA (1940-2008) Sevia Mahdaliza Khairil Amree Zainol

1 HISTORYOF COMMUNICATION IN MALAYSIA (1940-2008) Sevia Mahdaliza Khairil Amree Zainol 1.1 INTRODUCTION The Second World War was, in some ways, one of the lowest points in Malaysia's history. Japanese forces landed on the north- east border of Malaya on 8 December 194 1 and, in one month, succeeded in establishing their control of both Peninsula Malaya and Sabah and Sarawak. On 15 March 1942, Singapore surrendered. Singapore was renamed Shonan and became the centre of a regional administrative headquarters that incorporated the Straits Settlements, and the Federated Malay States and Sumatra. Much like the British who had installed residents in the Malay ruling houses fifty years earlier, the Japanese appointed local governors to each state. The only difference was that this time, it was the Sultans who were placed in the positions of advisors. The Unfederated Malay States, Perlis, Kedah, Kelantan and Terengganu found themselves back under the sovereignty of Thailand in 1942, when Thailand declared war on Britain and the USA. Most large scale economic activities grounded to a halt during the period of the War. The production of tin which was already falling before the War stopped almost completely. People turned their occupation away from the cultivation of commercial crops, concentrating instead on planting rice and vegetables to ensure they did not go hungry. [1] 2 Wireless Communication Technology in Malaysia 1.2 HISTORY BEGAN For the telecommunication industry, all activity not specifically related to the war effort came to a stand still. A young telegraph operator identified only as E.R. joined what was then the Post and Telecoms Department in 1941. -

Coms 200 | History of Communication Syllabus

COMS 200 | HISTORY OF COMMUNICATION SYLLABUS Department of Art History and Communication Studies, McGill University Instructors: Farah Atoui & Liza Tom Wednesdays and Fridays 4:05 - 5:25PM EST Winter 2021 Land acknowledgment: McGill University is situated on the traditional territory of the Kanien’kehà:ka, a place which has long served as a site of meeting and exchange amongst nations. We recognize and respect the Kanien’kehà:ka as the traditional custodians of the lands and waters on which we meet today. Contact Details Instructor: Instructor: Teaching Assistant: Farah Atoui (she/her/hers) Liza Tom (she/her/hers) Ann Brody [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Office hours: Office hours: Office hours: Monday 2-3pm Thursday 10-11am TBC COURSE DESCRIPTION This course is a critical overview of the sociopolitical histories of modern communication technologies that shaped the 19th and 20th centuries. The focus is on the conditions that produced these modern tools of communication as well as on their social and political ramifications. The course examines an array of technologies, media forms and institutions—from railway and telegraph networks, to early film, photography, radio and the museum—through a postcolonial lens, and maintains a comparative approach to communication that reads against the idea of Western modernity and technological progress. By focusing on the relation between culture and power, the course aims to shed light on the role played by these technologies and media in re/producing and expanding (colonial) power relations, structures, and ideologies, as well as on their emancipatory potential for various historical contexts. -

Genesis of the Media Concept

Genesis of the Media Concept John Guillory The medium through which works of art continue to influence later ages is always different from the one in which they affect their own age. —WALTER BENJAMIN1 1. Mimesis and Medium The word media hints at a rich philological history extending back to the Latin medius, best exemplified in the familiar narrative topos of clas- sical epic: in medias res. Yet the path by which this ancient word for “mid- dle” came to serve as the collective noun for our most advanced communication technologies is difficult to trace. The philological record informs us that the substantive noun medium was rarely connected with matters of communication before the later nineteenth century. The explo- sive currency of this word in the communicative environment of moder- nity has relegated the genesis of the media concept to a puzzling obscurity. This essay is an attempt to give an account of this genesis within the longer history of reflection on communication. It is not my purpose, then, to enter into current debates in media theory but to describe the philosophical preconditions of media discourse. I argue that the concept of a medium of communication was absent but wanted for the several centuries prior to its appearance, a lacuna in the philosophical tradition that exerted a distinctive pressure, as if from the future, on early efforts to theorize communication. These early efforts necessarily built on the discourse of the arts, a concept that included not only “fine” arts such as poetry and music but also the ancient arts of rhetoric, logic, and dialec- tic. -

Communication Theory

Communication Theory Wikibooks.org March 22, 2013 On the 28th of April 2012 the contents of the English as well as German Wikibooks and Wikipedia projects were licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license. An URI to this license is given in the list of figures on page 117. If this document is a derived work from the contents of one of these projects and the content was still licensed by the project under this license at the time of derivation this document has to be licensed under the same, a similar or a compatible license, as stated in section 4b of the license. The list of contributors is included in chapter Contributors on page 113. The licenses GPL, LGPL and GFDL are included in chapter Licenses on page 121, since this book and/or parts of it may or may not be licensed under one or more of these licenses, and thus require inclusion of these licenses. The licenses of the figures are given in the list of figures on page 117. This PDF was generated by the LATEX typesetting software. The LATEX source code is included as an attachment (source.7z.txt) in this PDF file. To extract the source from the PDF file, we recommend the use of http://www.pdflabs.com/tools/pdftk-the-pdf-toolkit/ utility or clicking the paper clip attachment symbol on the lower left of your PDF Viewer, selecting Save Attachment. After extracting it from the PDF file you have to rename it to source.7z. To uncompress the resulting archive we recommend the use of http://www.7-zip.org/. -

Four-Year Pathway Plan

FOUR-YEAR PATHWAY PLAN North Carolina Community College to Chowan University A.A. or A.S. to B.A. or B.S. Mass Communication, Communication Studies, B.A. NCCCS FIRST YEAR CU THIRD YEAR Fall Semester SHC Fall Semester SHC ACA 122 – College Transfer Success 1 LS 201 – LitSphere 1 ENG 111 – Writing & Inquiry 3 REL 101 – Understanding the Bible 3 Social/Behavioral Sciences (Any) 3 Global Learning Core 3 CIS 110 – Introduction to Computers 3 COMM 135 – Media Writing 3 Elective 3 COMM 225 – Digital and Online Media 3 Elective 3 Communication Studies Concentration* 3 Total SHC 16 Total SHC 16 Spring Semester SHC Spring Semester SHC ENG 112 – Writing/Research in the Disciplines 3 LS 202 – LitSphere 1 Communications/Humanities/Fine Arts (Any) 3 Global Learning Core 3 Social/Behavioral Sciences (Any) 3 COMM 230 – Mass Media and Society 3 COMM 231 – Public Speaking 3 COMM 335 – Grammar for Media COMM 110 – Introduction to Communication 3 Professionals 3 Communication Studies Concentration* 3 Elective 1 Total SHC 15 Total SHC 14 NCCCS SECOND YEAR CU FOURTH YEAR Fall Semester SHC Fall Semester SHC Communications/Humanities/Fine Arts (Any) 3 Global Learning Core 3 Social/Behavioral Sciences (Any) 3 COMM 340 – Research Methods in Mass Natural Sciences (Any) 4 Communication 3 Elective 3 COMM 435 – Theories of Mass Elective 3 Communication 3 Communication Studies Concentration* 3 Communication Studies Elective** 3 Total SHC 16 Total SHC 15 Spring Semester SHC Spring Semester SHC Math (Any) 3‐4 Global Learning Core 3 Communications/Humanities/Fine Arts -

Features of Media Multitasking Experiences

WP2 MEDIA MULTITASKING D2.3.3.6 FEATURES OF MEDIA MULTITASKING EXPERIENCES Media Multitasking D2.3.3.6 Features of media multitasking experience s Authors: Maria Viitanen, Stina Westman, Teemu Kinnunen, Pirkko Oittinen Confidentiality: Consortium Date and status: August 31st , 2012, version 0.1 This work was supported by TEKES as part of the next Media programme of TIVIT (Finnish Strategic Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation in the field of ICT) Next Media - a Tivit Programme Phase 3 (1.1.–31.12.2012) Version history: Version Date State Author(s) OR Remarks (draft/ /update/ final) Editor/Contributors 0.1 31 st August MV, SW, TK, PO Review version {Participants = all research organisations and companies involved in the making of the deliverable} Participants Name Organisation Maria Viitanen Aalto University Researchers Stina Westman Department of Media Teemu Kinnunen Technology Pirkko Oittinen next Media www.nextmedia.fi www.tivit.fi WP2 MEDIA MULTITASKING D2.3.3.6 FEATURES OF MEDIA MULTITASKING EXPERIENCES 1 (40) Next Media - a Tivit Programme Phase 3 (1.1.–31.12.2012) Executive Summary Media multitasking is gaining attention as a phenomenon affecting media consumption especially among younger generations. From both social and technical viewpoints it is an important shift in media use, affecting and providing opportunities for content providers, system designers and advertisers alike. Media multitasking may be divided into media multitasking which refers to using several media together and multitasking with media, which consists of combining non- media activities with media use. In this deliverable we review research on multitasking from various disciplines: cognitive psychology, education, human-computer interaction, information science, marketing, media and communication studies, and organizational studies. -

Communication Studies (COMM) 1 Communication Studies (COMM)

Communication Studies (COMM) 1 Communication Studies (COMM) Search COMM Courses using FocusSearch (http:// COMM 1131. Sex, Relationships, and Communication. (4 Hours) catalog.northeastern.edu/class-search/?subject=COMM) Focuses on communication within the context of close relationships. Topics covered include the role of communication in interpersonal COMM 1000. Communication Studies at Northeastern. (1 Hour) attraction, relationship development, relationship maintenance, and Designed to provide a unique opportunity to engage faculty, professional relationship dissolution. Examines how communication impacts staff, and peer mentors in small group discussions. Introduces students relationship quality and commitment. Offers students an opportunity to to the College of Arts, Media and Design. Offers students an opportunity apply what they learn in the course to their personal and professional to learn about the communication studies major and to explore the lives. different areas of emphasis offered by the department. As part of the course, students are expected to prepare a detailed plan of study and are Attribute(s): NUpath Societies/Institutions introduced to the co-op program and meet their academic co-op advisor. COMM 1210. Persuasion and Rhetoric. (4 Hours) Seeks to teach students to be more astute receivers and producers of COMM 1101. Introduction to Communication Studies. (4 Hours) persuasive messages by learning how to dissect them. Examines both Surveys the field of communication studies. Covers major theories classical and contemporary theories of persuasion, after which students and methodological approaches in communication studies and consider “persuasion in action”—how persuasion is used in everyday situates communication within larger social, political, and economic language, nonverbal communication, sales techniques, politics, and institutions. -

Media Studies and Production Diploam Program Guide

Media Studies and Production Diploma - 31 credits Program Area: Media Studies (Fall 2019) ***REMEMBER TO REGISTER EARLY*** Program Description Required Courses This program is designed to Course Course Title Credits Term prepare the graduate for a wide MCOM 1400* Intro to Mass 3 Communication variety of positions in media MCOM 1420* Digital Video 3 production. Graduates are trained Production for jobs ranging from highly visible MCOM 1422* Audio for the Media 3 on-the-air assignments to positions ENGL 1106* College Composition I 3 on production or news teams. MCOM 1424 Digital Video Editing 3 Graduates can also gain skills MCOM 1426 Project/Production 3 needed for careers in multimedia, Management DVD authoring, film style MCOM 1428* Interactive Media 3 production, and media project & Production MCOM 1795* Portfolio Production 1 production management. Lake MCOM 1797* Media Studies 3 Superior College media studies Internship students receive valuable hands- Electives 6 on experience in LSC’s own audio (refer to Table 1) and video studios, as well as Total credits 31 through internships and *Requires a prerequisite or instructor’s consent experiences at local broadcast stations and media agencies. Program Outcomes Upon graduation, students will be able to: • Shoot and edit single camera media productions using both analog and digital equipment. • Participate in cooperative media production teams. • Voice, record, edit, and produce audio projects, promotions, and commercials using both analog and digital equipment. • Use terms and techniques common to media production and process. Pre-program Requirements Successful entry into this program requires a specific level of skill in the areas of English, mathematics, and reading.