1 Notes to García and González 2 Notes to Nelson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

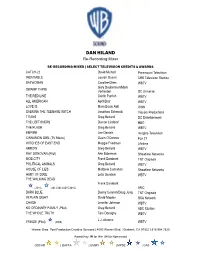

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer RE-RECORDING MIXER | SELECT TELEVISION CREDITS & AWARDS CATCH-22 David Michod Paramount Television INSATIABLE Lauren Gussis CBS Television Studios BATWOMAN Caroline Dries WBTV Gary Dauberman/Mark SWAMP THING Verheiden DC Universe THE RED LINE Cairlin Parrish WBTV ALL AMERICAN April Blair WBTV LOVE IS Mara Brock Akil OWN SABRINA THE TEENAGE WITCH Jonathan Schmock Viacom Productions TITANS Greg Berlanti DC Entertainment THE LEFTOVERS Damon Lindelof HBO THE FLASH Greg Berlanti WBTV EMPIRE Lee Daniels Imagine Television CINNAMON GIRL (TV Movie) Gavin O'Connor Fox 21 WITCHES OF EAST END Maggie Friedman Lifetime ARROW Greg Berlanti WBTV RAY DONOVAN (Pilot) Ann Biderman Showtime Networks MOB CITY Frank Darabont TNT Originals POLITICAL ANIMALS Greg Berlanti WBTV HOUSE OF LIES Matthew Carnahan Showtime Networks HART OF DIXIE Leila Gerstein WBTV THE WALKING DEAD Frank Darabont (2010) (2012/2014/2015/2016) AMC DARK BLUE Danny Cannon/Doug Jung TNT Originals IN PLAIN SIGHT David Maples USA Network CHASE Jennifer Johnson WBTV NO ORDINARY FAMILY (Pilot) Greg Berlanti ABC Studios THE WHOLE TRUTH Tom Donaghy WBTV J.J. Abrams FRINGE (Pilot) (2009) WBTV Warner Bros. Post Production Creative Services | 4000 Warner Blvd. | Burbank, CA 91522 | 818.954.7825 Award Key: W for Win | N for Nominated OSCAR | BAFTA | EMMY | MPSE | CAS LIMELIGHT (Pilot) David Semel, WBTV HUMAN TARGET Jonathan E. Steinberg WBTV EASTWICK Maggie Friedman WBTV V (Pilot) Kenneth Johnson WBTV TERMINATOR: THE SARAH CONNER Josh Friedman CHRONICLES WBTV CAPTAIN -

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written By

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written by Sam Catlin, Vince Gilligan, Peter Gould, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Moira Walley-Beckett; AMC The Good Wife, Written by Meredith Averill, Leonard Dick, Keith Eisner, Jacqueline Hoyt, Ted Humphrey, Michelle King, Robert King, Erica Shelton Kodish, Matthew Montoya, J.C. Nolan, Luke Schelhaas, Nichelle Tramble Spellman, Craig Turk, Julie Wolfe; CBS Homeland, Written by Henry Bromell, William E. Bromell, Alexander Cary, Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Barbara Hall, Patrick Harbinson, Chip Johannessen, Meredith Stiehm, Charlotte Stoudt, James Yoshimura; Showtime House Of Cards, Written by Kate Barnow, Rick Cleveland, Sam R. Forman, Gina Gionfriddo, Keith Huff, Sarah Treem, Beau Willimon; Netflix Mad Men, Written by Lisa Albert, Semi Chellas, Jason Grote, Jonathan Igla, Andre Jacquemetton, Maria Jacquemetton, Janet Leahy, Erin Levy, Michael Saltzman, Tom Smuts, Matthew Weiner, Carly Wray; AMC COMEDY SERIES 30 Rock, Written by Jack Burditt, Robert Carlock, Tom Ceraulo, Luke Del Tredici, Tina Fey, Lang Fisher, Matt Hubbard, Colleen McGuinness, Sam Means, Dylan Morgan, Nina Pedrad, Josh Siegal, Tracey Wigfield; NBC Modern Family, Written by Paul Corrigan, Bianca Douglas, Megan Ganz, Abraham Higginbotham, Ben Karlin, Elaine Ko, Steven Levitan, Christopher Lloyd, Dan O’Shannon, Jeffrey Richman, Audra Sielaff, Emily Spivey, Brad Walsh, Bill Wrubel, Danny Zuker; ABC Parks And Recreation, Written by Megan Amram, Donick Cary, Greg Daniels, Nate DiMeo, Emma Fletcher, Rachna -

Dexter – James Manos Jr

Educación sentimental-televisiva La casualidad ha querido que encontrara el tiempo para escribir estas líneas pasando las vacaciones en una casa de campo del con- dado de Yorkshire, en el norte de Inglaterra, a escasas cinco millas del castillo de Howard. Esta mansión vecina se hizo popular en el siglo XX por alojar parte de la filmación de una película ilustre, Barry Lyndon, de Stanley Kubrick, y de una serie no menos distinguida: Retorno a Brideshead, la adaptación de Granada Television del libro homónimo de Evelyn Waugh que lanzó al estrellato a un joven Je- remy Irons. No es que hubiera escogido este destino vacacional en base a la proximidad de esta country house tricentenaria de la que guardo tan hondo recuerdo televisivo. Pero mentiría si dijera que no me alegré al conocer que la iba a tener tan a mano. De la misma manera que me complacería ir de vacaciones al estado de Washington, en Esta- dos Unidos, sabiendo que Snoqualmie y North Bend, los dos pue- blos en los que se rodaron los exteriores de Twin Peaks, están cerca, o viajaría a Gales con la ilusión de poder visitar en algún momento Portmeirion, la muy peculiar villa costera en la que se grabó El pri- sionero. Son todos ellos lugares que, gracias a las ficciones televisivas que durante un tiempo albergaron, dejaron algo dentro de mí; o quizá dejé yo algo dentro de ellos y ahora me gustaría saber de qué se trata. No sé. Tanto Twin Peaks como El prisionero aparecen seleccionadas por Quim Casas en la lista de 75 series que conforma este libro. -

MATT VOWLES, CAS Re-Recording Mixer | Supervising Sound Editor

MATT VOWLES, CAS Re-Recording Mixer | Supervising Sound Editor RE-RECORDING MIXER | SUPERVISING SOUND EDITOR | SELECT TELEVISION CREDITS *THE FLIGHT ATTENDENT Steve Yockey WBTV *COUNCIL OF DADS Tony Phelan/Joan Rater Universal Television *DISPATCHES FROM ELSEWHERE Jason Segel AMC Networks *TREADSTONE Tim Kring USA Network Brandon Margolis/Brandon *L.A.'S FINEST Sonnier Sony Pictures Television *QUANTICO Joshua Safran ABC Studios *RIVERDALE Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa WBTV *CODE BLACK Michael Seitzman ABC Studios *I’M DYING UP HERE (Season 1) David Flebotte/Jim Carrey Showtime Networks *GREENLEAF Craig Wright Lionsgate *INTO THE BADLANDS Alfred Gough/Miles Millar AMC Studios SOUTHLAND (Seasons 1-5) Ann Biderman WBTV LONGMIRE (Season 1 & 2) Hunt Baldwin/John Coveny Warner Horizon Television *LUCK (Pilot) David Milch HBO *SHAMELESS (Pilot) John Wells Showtime Networks IN TREATMENT (Seasons 1 & 2) Rodrigo Garcia HBO Entertainment RE-RECORDIN MIXER | SELECT INTERNATIONAL FEATURE CREDITS CAPTAIN AMERICA (Foreign Version) Joe Johnston Paramount Pictures TRANSFORMERS 3 (International Trailers) Michael Bay Paramount Pictures HARRY POTTER AND THE DEATHLY HOLLOWS David Yates – PART 1& 2 (Foreign Version) Warner Bros. HAPPY FEET TWO George Miller Warner Bros. HORRIBLE BOSSES 2 Seth Gordon Warner Bros. THOR (Foreign Version) Kenneth Branagh Paramount Pictures DUE DATE (Foreign Version) Todd Phillips Warner Bros. INCEPTION (Foreign Version) Christopher Nolan Warner Bros. IRON MAN 2 (Foreign Version) Jon Favreau Marvel Studios Warner Bros. Post Production Creative Services | 4000 Warner Blvd. | Burbank, CA 91522 | 818.954.2646 *Re-Recording Credit Only | **Supervising Sound Editor Only Award Key: W for Win | N for Nominated OSCAR | BAFTA | EMMY | MPSE | CAS | LEGEND OF THE GUARDIANS (Foreign Version) Zack Snyder Warner Bros. -

Liste Alphabétique Des DVD Du Club Vidéo De La Bibliothèque

Liste alphabétique des DVD du club vidéo de la bibliothèque Merci à nos donateurs : Fonds de développement du collège Édouard-Montpetit (FDCEM) Librairie coopérative Édouard-Montpetit Formation continue – ÉNA Conseil de vie étudiante (CVE) – ÉNA septembre 2013 A 791.4372F251sd 2 fast 2 furious / directed by John Singleton A 791.4372 D487pd 2 Frogs dans l'Ouest [enregistrement vidéo] = 2 Frogs in the West / réalisation, Dany Papineau. A 791.4372 T845hd Les 3 p'tits cochons [enregistrement vidéo] = The 3 little pigs / réalisation, Patrick Huard . A 791.4372 F216asd Les 4 fantastiques et le surfer d'argent [enregistrement vidéo] = Fantastic 4. Rise of the silver surfer / réalisation, Tim Story. A 791.4372 Z587fd 007 Quantum [enregistrement vidéo] = Quantum of solace / réalisation, Marc Forster. A 791.4372 H911od 8 femmes [enregistrement vidéo] / réalisation, François Ozon. A 791.4372E34hd 8 Mile / directed by Curtis Hanson A 791.4372N714nd 9/11 / directed by James Hanlon, Gédéon Naudet, Jules Naudet A 791.4372 D619pd 10 1/2 [enregistrement vidéo] / réalisation, Daniel Grou (Podz). A 791.4372O59bd 11'09''01-September 11 / produit par Alain Brigand A 791.4372T447wd 13 going on 30 / directed by Gary Winick A 791.4372 Q7fd 15 février 1839 [enregistrement vidéo] / scénario et réalisation, Pierre Falardeau. A 791.4372 S625dd 16 rues [enregistrement vidéo] = 16 blocks / réalisation, Richard Donner. A 791.4372D619sd 18 ans après / scénario et réalisation, Coline Serreau A 791.4372V784ed 20 h 17, rue Darling / scénario et réalisation, Bernard Émond A 791.4372T971gad 21 grams / directed by Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu ©Cégep Édouard-Montpetit – Bibliothèque de l’École nationale d'aérotechnique - Mise à jour : 30 septembre 2013 Page 1 A 791.4372 T971Ld 21 Jump Street [enregistrement vidéo] / réalisation, Phil Lord, Christopher Miller. -

Film Locations in San Francisco

Film Locations in San Francisco Title Release Year Locations A Jitney Elopement 1915 20th and Folsom Streets A Jitney Elopement 1915 Golden Gate Park Greed 1924 Cliff House (1090 Point Lobos Avenue) Greed 1924 Bush and Sutter Streets Greed 1924 Hayes Street at Laguna The Jazz Singer 1927 Coffee Dan's (O'Farrell Street at Powell) Barbary Coast 1935 After the Thin Man 1936 Coit Tower San Francisco 1936 The Barbary Coast San Francisco 1936 City Hall Page 1 of 588 10/02/2021 Film Locations in San Francisco Fun Facts Production Company The Essanay Film Manufacturing Company During San Francisco's Gold Rush era, the The Essanay Film Manufacturing Company Park was part of an area designated as the "Great Sand Waste". In 1887, the Cliff House was severely Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) damaged when the schooner Parallel, abandoned and loaded with dynamite, ran aground on the rocks below. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Warner Bros. Pictures The Samuel Goldwyn Company The Tower was funded by a gift bequeathed Metro-Goldwyn Mayer by Lillie Hitchcock Coit, a socialite who reportedly liked to chase fires. Though the tower resembles a firehose nozzle, it was not designed this way. The Barbary Coast was a red-light district Metro-Goldwyn Mayer that was largely destroyed in the 1906 earthquake. Though some of the establishments were rebuilt after the earthquake, an anti-vice campaign put the establishments out of business. The dome of SF's City Hall is almost a foot Metro-Goldwyn Mayer Page 2 of 588 10/02/2021 Film Locations in San Francisco Distributor Director Writer General Film Company Charles Chaplin Charles Chaplin General Film Company Charles Chaplin Charles Chaplin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Eric von Stroheim Eric von Stroheim Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Eric von Stroheim Eric von Stroheim Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Eric von Stroheim Eric von Stroheim Warner Bros. -

General Coporation Tax Allocation Percentage Report 2003

2003 General Corporation Tax Allocation Percentage Report Page - 1- @ONCE.COM INC .02 A AND J TITLE SEARCHING CO INC .01 @RADICAL.MEDIA INC 25.08 A AND L AUTO RENTAL SERVICES INC 1.00 @ROAD INC 1.47 A AND L CESSPOOL SERVICE CORP 96.51 "K" LINE AIR SERVICE U.S.A. INC 20.91 A AND L GENERAL CONTRACTORS INC 2.38 A OTTAVINO PROPERTY CORP 29.38 A AND L INDUSTRIES INC .01 A & A INDUSTRIAL SUPPLIES INC 1.40 A AND L PEN MANUFACTURING CORP 53.53 A & A MAINTENANCE ENTERPRISE INC 2.92 A AND L SEAMON INC 4.46 A & D MECHANICAL INC 64.91 A AND L SHEET METAL FABRICATIONS CORP 69.07 A & E MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS INC 77.46 A AND L TWIN REALTY INC .01 A & E PRO FLOOR AND CARPET .01 A AND M AUTO COLLISION INC .01 A & F MUSIC LTD 91.46 A AND M ROSENTHAL ENTERPRISES INC 51.42 A & H BECKER INC .01 A AND M SPORTS WEAR CORP .01 A & J REFIGERATION INC 4.09 A AND N BUSINESS SERVICES INC 46.82 A & M BRONX BAKING INC 2.40 A AND N DELIVERY SERVICE INC .01 A & M FOOD DISTRIBUTORS INC 93.00 A AND N ELECTRONICS AND JEWELRY .01 A & M LOGOS INTERNATIONAL INC 81.47 A AND N INSTALLATIONS INC .01 A & P LAUNDROMAT INC .01 A AND N PERSONAL TOUCH BILLING SERVICES INC 33.00 A & R CATERING SERVICE INC .01 A AND P COAT APRON AND LINEN SUPPLY INC 32.89 A & R ESTATE BUYERS INC 64.87 A AND R AUTO SALES INC 16.50 A & R MEAT PROVISIONS CORP .01 A AND R GROCERY AND DELI CORP .01 A & S BAGEL INC .28 A AND R MNUCHIN INC 41.05 A & S MOVING & PACKING SERVICE INC 73.95 A AND R SECURITIES CORP 62.32 A & S WHOLESALE JEWELRY CORP 78.41 A AND S FIELD SERVICES INC .01 A A A REFRIGERATION SERVICE INC 31.56 A AND S TEXTILE INC 45.00 A A COOL AIR INC 99.22 A AND T WAREHOUSE MANAGEMENT CORP 88.33 A A LINE AND WIRE CORP 70.41 A AND U DELI GROCERY INC .01 A A T COMMUNICATIONS CORP 10.08 A AND V CONTRACTING CORP 10.87 A A WEINSTEIN REALTY INC 6.67 A AND W GEMS INC 71.49 A ADLER INC 87.27 A AND W MANUFACTURING CORP 13.53 A AND A ALLIANCE MOVING INC .01 A AND X DEVELOPMENT CORP. -

Myths and the Criminal Justice System 5 2 It All Starts with Crime 15 3 What Do We Know About Crime? 25 4 Are Criminals Born This Way? 39

SECOND EDITION The American CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM A Concise Guide to Cops, Courts, Corrections, and Victims BY JAMES WINDELL WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY Bassim Hamadeh, CEO and Publisher Kassie Graves, Director of Acquisitions Jamie Giganti, Senior Managing Editor Jess Estrella, Senior Graphic Designer John Remington, Senior Field Acquisitions Editor Natalie Lakosil, Senior Licensing Manager Allie Kiekhofer and Kaela Martin, Associate Editors Copyright © 2017 by Cognella, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information retrieval system without the written permis- sion of Cognella, Inc. Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for iden- tification and explanation without intent to infringe. Cover image copyright © Depositphotos/slickspics. copyright © Depositphotos/100ker. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-63487-804-3 (pbk) / 978-1-63487-805-0 (br) Contents INTRODUCTION 1 PART ONE Myths and Realities in the Criminal Justice System 3 1 Myths and the Criminal Justice System 5 2 It All Starts with Crime 15 3 What Do We Know about Crime? 25 4 Are Criminals Born This Way? 39 PART TWO The Law Enforcement Response to Crime 51 5 How Does the Criminal Justice System Respond to Crime? 53 6 Investigating Crime and the Rule of Law 65 7 Problems -

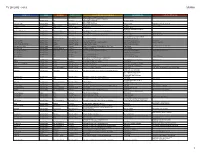

Tv Shows - 2019 Drama

TV SHOWS - 2019 DRAMA SHOW TITLE GENRE NETWORK SEASON STATUS STUDIO / PRODUCTION COMPANIES SHOWRUNNER(S) EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS 68 Whiskey Episodic Drama Paramount Network Ordered to Series CBS TV Studios / Imagine Television Roberto Benabib Fox TV Studios / 20th Century Fox Television, 911 Episodic Drama Fox Renewed Ryan Murphy Productions Timothy P. Minear, 20th Century Fox TV / 9-1-1: Lone Star Episodic Drama Fox Ordered to Series Ryan Murphy Productions Ryan P. Murphy Brad Falchuk; Timothy P. Minear A Million Little Things Episodic Drama ABC Television Renewed ABC Studios / Kapital Entertainment DJ Nash James Griffiths A Teacher Drama FX Network Ordered To Series FX Productions Hannah M. Fidell Jed Whedon; Maurissa Tancharoen; Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. Episodic Drama ABC Television Renewed ABC Studios / Marvel Entertainment; Mutant Enemy Jeffrey Bell Alive Episodic Drama CBS Entertainment Not Picked Up CBS TV Studios Jason Tracey Robert Doherty All American Episodic Drama CW Network Renewed Warner Bros Television / Berlanti Productions Nkechi Carroll, Gregory G. Berlanti Greg Spottiswood; Leonard Goldstein; All Rise Episodic Drama CBS Entertainment Ordered to Series Warner Bros Television Michael Robin; Gil Garcetti Almost Paradise Episodic Drama WGN America Ordered to Series Electric Entertainment Gary Rosen; Dean Devlin Marc Roskin Amazing Stories Episodic Drama Apple Ordered To Series Universal Television LLC / Amblin Television Adam Horowitz; Edward Kitsis David H. Goodman Amazon/Russo Bros Project Episodic Drama Amazon Ordered To Series Amazon Studios / AGBO Anthony Russo; Joe Russo American Crime Story Episodic Drama FX Network Renewed Fox 21; FX Productions / B2 Entertainment; Color Force Ryan Murphy Brad Falchuk; D V. -

Functions of Intermediality in the Simpsons

Functions of Intertextuality and Intermediality in The Simpsons Der Fakultät für Geisteswissenschaften der Universität Duisburg-Essen zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) eingereichte Dissertation von Wanja Matthias Freiherr von der Goltz Datum der Disputation: 05. Juli 2011 Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Josef Raab Prof. Dr. Jens Gurr Table of Contents List of Figures...................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 5 1.1 The Simpsons: Postmodern Entertainment across Generations ................ 5 1.2 Research Focus .............................................................................................11 1.3 Choice of Material ..........................................................................................16 1.4 Current State of Research .............................................................................21 2. Text-Text Relations in Television Programs ....................................... 39 2.1 Poststructural Intertextuality: Bakhtin, Kristeva, Barthes, Bloom, Riffaterre .........................................................................................................39 2.2 Forms and Functions of Intertextual References ........................................48 2.3 Intertextuality and Intermediality ..................................................................64 2.4 Television as a -

Ntyrepoit Issue Insidc: Eabasnapshot Ohdemga" Legenuary LY

hi T , »nTYrepoiT issue insiDC: EABASnaPSHOT OHDemGa" LeGenuarY LY. tJ!r J FUDHa & THMOfflWBanK pirncs THC rie w Green JWBLC minoriTic m ay ?8 0 - \<Ii4 issue v2 0 5 > SOUTH LanD*s MifHaeL CUDLIT 1 11 HEppiir ouTTOTHe^ouTer BanKS 0 *7AA 7o"25134 7 ^eLeBriTYvrvai q-munity: cbus Legacy Fund of The Columbus Foundation cating their representatives every May. Now, we need to urban leadership initiatives. Gilbride-Brown has Honors Lynn Greer May 25 talk to our Senators about passing EHEA through the worked to create and implement trainings and re Senate so that Governor Strickland can sign it into law source-sharing strategies on social justice projects. In The Legacy Fund of The Colum bus Foundation will before the end of 2010! addition, she is an expert in the assessment of data honor Lynn Greer s relentless pursuit of equality and regarding urban \outh leadership in the community- her devotion to the Central Ohio gay, lesbian, bisexual But make no mistake, the EHEA will not pass the Sen based learning context Gilbride-Brown has served as ate ifwedon'tworkfor it. an instructor atthe Department of Educational Policy and transgendered (GLBT) and allied communities at and Leadership of The Ohio State University. Wiile at a May 25 event at The Columbus Foundation (1234 OSU she taught courses on leadership and sxial jus East Broad St 43205). Bn ng your story to the statehouse on May 19th to makea difference. Don't be late! Register before May tice and secured funding through a variety of grants to 5th to join us on this important day. -

We're #1 Comedy Gets a Chair Year in Review Not Your

FALL 2010 INMOTION IMDW Enamed’RE top # games1 program HonorsCOM actorE DandY philanthropist GETS A Jack C OakieHAIR NotYE SlowingAR I DownN REVIEW WomenNOT of YCinematicOUR Arts M hostA forumMA’S INDUSTRY UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Dean Elizabeth M. Daley INMOTION Senior Associate Dean, Fall 2010 External Relations Marlene Loadvine Associate Dean of Communications Stephanie Kluft Contributors Mel Cowan Cristy Lytal Justin Wilson Design Roberto A. Gomez PAGE 3 MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN Researchers Ryan Gilmour Contributing Photographers Carell Augustus PAGE 4 YEAR IN REVIEW Alan Baker Steve Cohn PAGE 6 Caleb Coppola SCA & THE ACADEMY Roberto A. Gomez PRINCESS GRACE AWARD BOARD OF COUNCILORS ALUMNI DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL PAGE 7 WCA FORUM Frank Price (Chair, John August ’94 NINA FOCH DVD Board of Councilors) Susan Downey ’95 Bob Ducsay ’86 Frank Biondi, Jr. Robert Greenblatt ’87 PAGE 8 THE STORYTELLERS John Calley Tom Hoberman Barry Diller Ramses Ishak ’92 Lee Gabler James Ishii ’76 PAGE 11 WE’RE #1 David Geffen Leslie Iwerks ’93 Brian T. Grazer Polly Cohen Johnsen ’95 Brad Grey Aaron Kaplan ’90 PAGE 12 BUILDING THE FUTURE Jeffrey Katzenberg Michael Lehmann ’85 SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT Alan Levine Laird Malamed ’94 Building Update George Lucas Michelle Manning ’81 Don Mattrick Andrew Marlowe ’92 Why I Give... Bill M. Mechanic Derek McLay Barry Meyer Andrew Millstein Sidney Poitier Neal Moritz ’85 PAGE 16 ALUMNI QUICKTAKES John Riccitiello Robert Osher ’81 Barney Rosenzweig Santiago Pozo ’86 Scott Sassa Shonda Rhimes ’94 PAGE 17 FACULTY QUICKTAKES Steven Spielberg Jay Roach ’86 John Wells Bruce Rosenblum ’79 Jim Wiatt Gary Rydstrom ’81 PAGE 18 TV AND FILMS IN RELEASE Paul Junger Witt Josh Schwartz David L.