Myths and the Criminal Justice System 5 2 It All Starts with Crime 15 3 What Do We Know About Crime? 25 4 Are Criminals Born This Way? 39

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

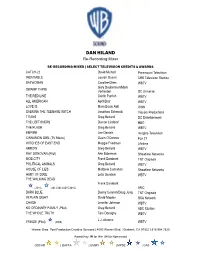

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer RE-RECORDING MIXER | SELECT TELEVISION CREDITS & AWARDS CATCH-22 David Michod Paramount Television INSATIABLE Lauren Gussis CBS Television Studios BATWOMAN Caroline Dries WBTV Gary Dauberman/Mark SWAMP THING Verheiden DC Universe THE RED LINE Cairlin Parrish WBTV ALL AMERICAN April Blair WBTV LOVE IS Mara Brock Akil OWN SABRINA THE TEENAGE WITCH Jonathan Schmock Viacom Productions TITANS Greg Berlanti DC Entertainment THE LEFTOVERS Damon Lindelof HBO THE FLASH Greg Berlanti WBTV EMPIRE Lee Daniels Imagine Television CINNAMON GIRL (TV Movie) Gavin O'Connor Fox 21 WITCHES OF EAST END Maggie Friedman Lifetime ARROW Greg Berlanti WBTV RAY DONOVAN (Pilot) Ann Biderman Showtime Networks MOB CITY Frank Darabont TNT Originals POLITICAL ANIMALS Greg Berlanti WBTV HOUSE OF LIES Matthew Carnahan Showtime Networks HART OF DIXIE Leila Gerstein WBTV THE WALKING DEAD Frank Darabont (2010) (2012/2014/2015/2016) AMC DARK BLUE Danny Cannon/Doug Jung TNT Originals IN PLAIN SIGHT David Maples USA Network CHASE Jennifer Johnson WBTV NO ORDINARY FAMILY (Pilot) Greg Berlanti ABC Studios THE WHOLE TRUTH Tom Donaghy WBTV J.J. Abrams FRINGE (Pilot) (2009) WBTV Warner Bros. Post Production Creative Services | 4000 Warner Blvd. | Burbank, CA 91522 | 818.954.7825 Award Key: W for Win | N for Nominated OSCAR | BAFTA | EMMY | MPSE | CAS LIMELIGHT (Pilot) David Semel, WBTV HUMAN TARGET Jonathan E. Steinberg WBTV EASTWICK Maggie Friedman WBTV V (Pilot) Kenneth Johnson WBTV TERMINATOR: THE SARAH CONNER Josh Friedman CHRONICLES WBTV CAPTAIN -

Bad Cops: a Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers Author(s): James J. Fyfe ; Robert Kane Document No.: 215795 Date Received: September 2006 Award Number: 96-IJ-CX-0053 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers James J. Fyfe John Jay College of Criminal Justice and New York City Police Department Robert Kane American University Final Version Submitted to the United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice February 2005 This project was supported by Grant No. 1996-IJ-CX-0053 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of views in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Small Episodes, Big Detectives

Small Episodes, Big Detectives A genealogy of Detective Fiction and its Relation to Serialization MA Thesis Written by Bernardo Palau Cabrera Student Number: 11394145 Supervised by Toni Pape Ph.D. Second reader Mark Stewart Ph.D. MA in Media Studies - Television and Cross-Media Culture Graduate School of Humanities June 29th, 2018 Acknowledgments As I have learned from writing this research, every good detective has a sidekick that helps him throughout the investigation and plays an important role in the case solving process, sometimes without even knowing how important his or her contributions are for the final result. In my case, I had two sidekicks without whom this project would have never seen the light of day. Therefore, I would like to thank my thesis supervisor Toni Pape, whose feedback and kind advice was of great help. Thank you for helping me focus on the important and being challenging and supportive at the same time. I would also like to thank my wife, Daniela Salas, who has contributed with her useful insight, continuous encouragement and infinite patience, not only in the last months but in the whole master’s program. “Small Episodes, Big Detectives” 2 Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 4 1. Literature Seriality in the Victorian era .................................................................... 8 1.1. The Pickwick revolution ................................................................................... 8 -

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written By

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written by Sam Catlin, Vince Gilligan, Peter Gould, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Moira Walley-Beckett; AMC The Good Wife, Written by Meredith Averill, Leonard Dick, Keith Eisner, Jacqueline Hoyt, Ted Humphrey, Michelle King, Robert King, Erica Shelton Kodish, Matthew Montoya, J.C. Nolan, Luke Schelhaas, Nichelle Tramble Spellman, Craig Turk, Julie Wolfe; CBS Homeland, Written by Henry Bromell, William E. Bromell, Alexander Cary, Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Barbara Hall, Patrick Harbinson, Chip Johannessen, Meredith Stiehm, Charlotte Stoudt, James Yoshimura; Showtime House Of Cards, Written by Kate Barnow, Rick Cleveland, Sam R. Forman, Gina Gionfriddo, Keith Huff, Sarah Treem, Beau Willimon; Netflix Mad Men, Written by Lisa Albert, Semi Chellas, Jason Grote, Jonathan Igla, Andre Jacquemetton, Maria Jacquemetton, Janet Leahy, Erin Levy, Michael Saltzman, Tom Smuts, Matthew Weiner, Carly Wray; AMC COMEDY SERIES 30 Rock, Written by Jack Burditt, Robert Carlock, Tom Ceraulo, Luke Del Tredici, Tina Fey, Lang Fisher, Matt Hubbard, Colleen McGuinness, Sam Means, Dylan Morgan, Nina Pedrad, Josh Siegal, Tracey Wigfield; NBC Modern Family, Written by Paul Corrigan, Bianca Douglas, Megan Ganz, Abraham Higginbotham, Ben Karlin, Elaine Ko, Steven Levitan, Christopher Lloyd, Dan O’Shannon, Jeffrey Richman, Audra Sielaff, Emily Spivey, Brad Walsh, Bill Wrubel, Danny Zuker; ABC Parks And Recreation, Written by Megan Amram, Donick Cary, Greg Daniels, Nate DiMeo, Emma Fletcher, Rachna -

An Open Letter to President Biden and Vice President Harris

An Open Letter to President Biden and Vice President Harris Dear President Biden and Vice President Harris, We, the undersigned, are writing to urge your administration to reconsider the United States Army Corps of Engineers’ use of Nationwide Permit 12 (NWP12) to construct large fossil fuel pipelines. In Memphis, Tennessee, this “fast-tracked” permitting process has given the green light to the Byhalia pipeline, despite the process wholly ignoring significant environmental justice issues and the threat the project potentially poses to a local aquifer which provides drinking water to one million people. The pipeline route cuts through a resilient, low-wealth Black community, which has already been burdened by seventeen toxic release inventory facilities. The community suffers cancer rates four times higher than the national average. Subjecting this Black community to the possible health effects of more environmental degradation is wrong. Because your administration has prioritized the creation of environmental justice, we knew knowledge of this project would resonate with you. The pipeline would also cross through a municipal well field that provides the communities drinking water. To add insult to injury, this area poses the highest seismic hazard in the Southeastern United States. The Corps purports to have satisfied all public participation obligations for use of NWP 12 on the Byhalia pipeline in 2016 – years before the pipeline was proposed. We must provide forums where communities in the path of industrial projects across the country can be heard. Neighborhoods like Boxtown and Westwood in Memphis have a right to participate in the creation of their own destinies and should never be ignored. -

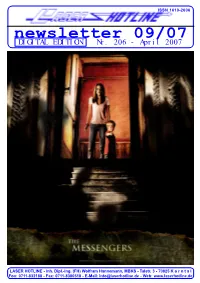

Newsletter 09/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 09/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 206 - April 2007 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 09/07 (Nr. 206) April 2007 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, und Fach. Wie versprochen gibt es dar- diesem Editorial auch gar nicht weiter liebe Filmfreunde! in unsere Reportage vom Widescreen aufhalten. Viel Spaß und bis zum näch- Es hat mal wieder ein paar Tage länger Weekend in Bradford. Also Lesestoff sten Mal! gedauert, aber nun haben wir Ausgabe satt. Und damit Sie auch gleich damit 206 unseres Newsletters unter Dach beginnen können, wollen wir Sie mit Ihr LASER HOTLINE Team LASER HOTLINE Seite 2 Newsletter 09/07 (Nr. 206) April 2007 US-Debüt der umtriebigen Pang-Brüder, die alle Register ihres Könnens ziehen, um im Stil von „Amityville Horror“ ein mit einem Fluch belegtes Haus zu Leben zu erwecken. Inhalt Roy und Denise Solomon ziehen mit ihrer Teenager-Tochter Jess und ihrem kleinen Sohn Ben in ein entlegenes Farmhaus in einem Sonnenblumenfeld in North Dakota. Dass sich dort womöglich übernatürliche Dinge abspielen könnten, bleibt von den Erwachsenen unbemerkt. Aber Ben und kurz darauf Jess spüren bald, dass nicht alles mit rechten Dingen zugeht. Weil ihr die Eltern nicht glauben wollen, recherchiert Jess auf eigene Faust und erfährt, dass sich in ihrem neuen Zuhause sechs Jahre zuvor ein bestialischer Mord abgespielt hat. Kritik Für sein amerikanisches Debüt hat sich das umtriebige Brüderpaar Danny und Oxide Pang („The Eye“) eine Variante von „Amityville Horror“ ausgesucht, um eine amerikanische Durchschnittsfamilie nach allen Regeln der Kunst mit übernatürlichem Terror zu überziehen. -

A Course Whose Time Has Come

A course whose time has come Paul R. Joseph Law is a central component of the democratic State. It defines the relation between the government and its people and sets the rules (and limits) of the restrained warfare of politics. Law becomes the battle ground for moral debates about issues such as abortion, discrimination, euthanasia, pornography and religion. Today we also debate the role Using science fiction and functioning of the legal system itself. Are lawyers ethical? Do judges usurp the legislative role? Are there too many ‘frivolous’ law materials to teach law. suits? Law and popular culture Where do the masses of people learn about the law? What shapes their views? Some peruse learned treatises, others read daily newspapers or tune in to the nightly news. Some watch key events, such as Supreme Court confirmation hearings, live, as they happen. Some have even been to law school. Many people also rely (whether consciously or not) on popular culture for their understanding of law and the legal system. Movies, television programs and other popular culture elements play a dual role, both shaping and reflecting our beliefs about the law. If popular culture helps to shape the public’s view about legal issues, it also reflects those views. By its nature as a mass commercial product, popular culture is unlikely to depart radically from images which the public will accept. By examining popular culture, we, the legally trained, can get an idea about how we and the things we do are understood and viewed by the rest of the body politic. -

Ed Begley, Jr

Ed Begley, Jr. When it comes to taking personal responsibility for the environment, few individuals can match the record of actor and activist Ed Begley, Jr. Known for turning up at Hollywood events on his bicycle, he has served as chairman of the Environmental Media Association and the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy. He serves on the boards of many organizations, including the Thoreau Institute and the Midnight Mission, His work has earned awards from numerous environmental groups including the California League of Conservation Voters, the Natural Resources Defense Council, the Coalition for Clean Air, Heal the Bay, the Santa Monica Baykeeper and the Cesar E. Chavez Foundation. Currently, he is the co-star of the hit Planet Green series Living with Ed, a look at the day-to-day realities of “living green” with his wife Rachelle Carson, who's not quite as enthusiastic about a rain barrel as he. The series has currently just finished airing its 3rd season. His first book, Living Like Ed, hit the streets nationally in February 2008, and the second book, Ed Begley's Guide to Sustainable Living came out in August of 2009. Inspired by the works of his Academy Award-winning father, Begley became an actor. He first came to audiences’ attention for his portrayal of Dr. Victor Ehrlich on the long-running hit television series St. Elsewhere, for which he received six Emmy nominations. Since then, Begley has moved easily between feature films, television and theatre projects. He has appeared in several Christopher Guest films, including A Mighty Wind, Best In Show and For Your Consideration. -

Dexter – James Manos Jr

Educación sentimental-televisiva La casualidad ha querido que encontrara el tiempo para escribir estas líneas pasando las vacaciones en una casa de campo del con- dado de Yorkshire, en el norte de Inglaterra, a escasas cinco millas del castillo de Howard. Esta mansión vecina se hizo popular en el siglo XX por alojar parte de la filmación de una película ilustre, Barry Lyndon, de Stanley Kubrick, y de una serie no menos distinguida: Retorno a Brideshead, la adaptación de Granada Television del libro homónimo de Evelyn Waugh que lanzó al estrellato a un joven Je- remy Irons. No es que hubiera escogido este destino vacacional en base a la proximidad de esta country house tricentenaria de la que guardo tan hondo recuerdo televisivo. Pero mentiría si dijera que no me alegré al conocer que la iba a tener tan a mano. De la misma manera que me complacería ir de vacaciones al estado de Washington, en Esta- dos Unidos, sabiendo que Snoqualmie y North Bend, los dos pue- blos en los que se rodaron los exteriores de Twin Peaks, están cerca, o viajaría a Gales con la ilusión de poder visitar en algún momento Portmeirion, la muy peculiar villa costera en la que se grabó El pri- sionero. Son todos ellos lugares que, gracias a las ficciones televisivas que durante un tiempo albergaron, dejaron algo dentro de mí; o quizá dejé yo algo dentro de ellos y ahora me gustaría saber de qué se trata. No sé. Tanto Twin Peaks como El prisionero aparecen seleccionadas por Quim Casas en la lista de 75 series que conforma este libro. -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

MATT VOWLES, CAS Re-Recording Mixer | Supervising Sound Editor

MATT VOWLES, CAS Re-Recording Mixer | Supervising Sound Editor RE-RECORDING MIXER | SUPERVISING SOUND EDITOR | SELECT TELEVISION CREDITS *THE FLIGHT ATTENDENT Steve Yockey WBTV *COUNCIL OF DADS Tony Phelan/Joan Rater Universal Television *DISPATCHES FROM ELSEWHERE Jason Segel AMC Networks *TREADSTONE Tim Kring USA Network Brandon Margolis/Brandon *L.A.'S FINEST Sonnier Sony Pictures Television *QUANTICO Joshua Safran ABC Studios *RIVERDALE Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa WBTV *CODE BLACK Michael Seitzman ABC Studios *I’M DYING UP HERE (Season 1) David Flebotte/Jim Carrey Showtime Networks *GREENLEAF Craig Wright Lionsgate *INTO THE BADLANDS Alfred Gough/Miles Millar AMC Studios SOUTHLAND (Seasons 1-5) Ann Biderman WBTV LONGMIRE (Season 1 & 2) Hunt Baldwin/John Coveny Warner Horizon Television *LUCK (Pilot) David Milch HBO *SHAMELESS (Pilot) John Wells Showtime Networks IN TREATMENT (Seasons 1 & 2) Rodrigo Garcia HBO Entertainment RE-RECORDIN MIXER | SELECT INTERNATIONAL FEATURE CREDITS CAPTAIN AMERICA (Foreign Version) Joe Johnston Paramount Pictures TRANSFORMERS 3 (International Trailers) Michael Bay Paramount Pictures HARRY POTTER AND THE DEATHLY HOLLOWS David Yates – PART 1& 2 (Foreign Version) Warner Bros. HAPPY FEET TWO George Miller Warner Bros. HORRIBLE BOSSES 2 Seth Gordon Warner Bros. THOR (Foreign Version) Kenneth Branagh Paramount Pictures DUE DATE (Foreign Version) Todd Phillips Warner Bros. INCEPTION (Foreign Version) Christopher Nolan Warner Bros. IRON MAN 2 (Foreign Version) Jon Favreau Marvel Studios Warner Bros. Post Production Creative Services | 4000 Warner Blvd. | Burbank, CA 91522 | 818.954.2646 *Re-Recording Credit Only | **Supervising Sound Editor Only Award Key: W for Win | N for Nominated OSCAR | BAFTA | EMMY | MPSE | CAS | LEGEND OF THE GUARDIANS (Foreign Version) Zack Snyder Warner Bros. -

Extensions of Remarks E643 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

April 2, 2003 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E643 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS REMEMBERING FORMER TRENTON promise and opportunity for this and future GLOBAL CHANGE RESEARCH AND MAYOR TOMMIE GOODWIN generations. DATA MANAGEMENT ACT OF 2003 The spirit of community service is alive and HON. JOHN S. TANNER thriving in Fremont, in some major part due to HON. MARK UDALL OF TENNESSEE the efforts of the members of the Mission San OF COLORADO IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Jose Rotary Club. I am honored to commend IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Wednesday, April 2, 2003 the Mission San Jose Rotary Club for its 20 Wednesday, April 2, 2003 years of generous service to the community. Mr. TANNER. Mr. Speaker, today I want to Mr. UDALL of Colorado. Mr. Speaker, today tell you about Tommie Goodwin, a fine public I am pleased to introduce the Global Change servant who dedicated himself to the people of f Research and Data Management Act of 2003. This bill updates the existing law that formally Tennessee during a distinguished 20-year ten- RECOGNITION TO MR. BILL CLARK ure as mayor of the City of Trenton, Ten- established the U.S. Global Change Research nessee. Program (USGCRP) in 1990. This bill is also Tommie first became mayor of Trenton in similar to the Global Change Research and 1983 and served honorably in that capacity HON. FRANK PALLONE, JR. Data Management Act that I introduced in the until his passing last year. Under Mayor Good- OF NEW JERSEY 107th Congress. Over the past decade, the USGCRP has win’s leadership, our community made great IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES strides in economic development and improve- significantly advanced our scientific knowledge ments in the quality of life of our citizens.