Redalyc.ITALY's EUROPEAN POLICY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carlo Azeglio Ciampi

Carlo Azeglio Ciampi Italia, Primer ministro (1993-1994) y presidente de la República (1999-2006) Duración del mandato: 18 de Maig de 1999 - de de Nacimiento: Livorno, provincia de Livorno, región de Toscana, 09 de Desembre de 1920 Defunción: Roma, región de Lacio, 16 de Setembre de 2016</p> Partido político: sin filiación Professió: Funcionario de banca Resumen http://www.cidob.org 1 of 3 Biografía Cursó estudios en Pisa en su Escuela Normal Superior, por la que se diplomó en 1941, y en su Universidad, por la que en 1946 obtuvo una doble licenciatura en Derecho y Letras. Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial sirvió en el Ejército italiano y tras la caída de Mussolini en 1943 estuvo con los partisanos antinazis. En 1945 militó en el Partido de Acción de Ferruccio Parri, pero pronto se desvinculó de cualquier organización política. En 1946 entró a trabajar por la vía de oposiciones en el Banco de Italia, institución donde desarrolló toda su carrera hasta la cúspide. Sucesivamente fue técnico en el departamento de investigación económica (1960-1970), jefe del departamento (1970-1973), secretario general del Banco (1973-1976), vicedirector general (1976-1978), director general (1978-1979) y, finalmente, gobernador (1979-1993). Considerado un economista de formación humanista, Ciampi salvaguardó la independencia del banco del Estado y se labró una imagen de austeridad y apego al trabajo. Como titular representó a Italia en las juntas de gobernadores de diversas instituciones financieras internacionales. Con su elección el 26 de abril de 1993 por el presidente de la República Oscar Luigi Scalfaro (por primera vez sin consultar a los partidos) para reemplazar a Giuliano Amato, Ciampi se convirtió en el primer jefe de Gobierno técnico, esto es, no adscrito a ninguna formación, desde 1945, si bien algunos líderes políticos insistieron en sus simpatías democristianas. -

October 22, 1962 Amintore Fanfani Diaries (Excepts)

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified October 22, 1962 Amintore Fanfani Diaries (excepts) Citation: “Amintore Fanfani Diaries (excepts),” October 22, 1962, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Italian Senate Historical Archives [the Archivio Storico del Senato della Repubblica]. Translated by Leopoldo Nuti. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/115421 Summary: The few excerpts about Cuba are a good example of the importance of the diaries: not only do they make clear Fanfani’s sense of danger and his willingness to search for a peaceful solution of the crisis, but the bits about his exchanges with Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs Carlo Russo, with the Italian Ambassador in London Pietro Quaroni, or with the USSR Presidium member Frol Kozlov, help frame the Italian position during the crisis in a broader context. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: Italian Contents: English Translation The Amintore Fanfani Diaries 22 October Tonight at 20:45 [US Ambassador Frederick Reinhardt] delivers me a letter in which [US President] Kennedy announces that he must act with an embargo of strategic weapons against Cuba because he is threatened by missile bases. And he sends me two of the four parts of the speech which he will deliver at midnight [Rome time; 7 pm Washington time]. I reply to the ambassador wondering whether they may be falling into a trap which will have possible repercussions in Berlin and elsewhere. Nonetheless, caught by surprise, I decide to reply formally tomorrow. I immediately called [President of the Republic Antonio] Segni in Sassari and [Foreign Minister Attilio] Piccioni in Brussels recommending prudence and peace for tomorrow’s EEC [European Economic Community] meeting. -

30Years 1953-1983

30Years 1953-1983 Group of the European People's Party (Christian -Demoeratie Group) 30Years 1953-1983 Group of the European People's Party (Christian -Demoeratie Group) Foreword . 3 Constitution declaration of the Christian-Democratic Group (1953 and 1958) . 4 The beginnings ............ ·~:.................................................. 9 From the Common Assembly to the European Parliament ........................... 12 The Community takes shape; consolidation within, recognition without . 15 A new impetus: consolidation, expansion, political cooperation ........................................................... 19 On the road to European Union .................................................. 23 On the threshold of direct elections and of a second enlargement .................................................... 26 The elected Parliament - Symbol of the sovereignty of the European people .......... 31 List of members of the Christian-Democratic Group ................................ 49 2 Foreword On 23 June 1953 the Christian-Democratic Political Group officially came into being within the then Common Assembly of the European Coal and Steel Community. The Christian Democrats in the original six Community countries thus expressed their conscious and firm resolve to rise above a blinkered vision of egoistically determined national interests and forge a common, supranational consciousness in the service of all our peoples. From that moment our Group, whose tMrtieth anniversary we are now celebrating together with thirty years of political -

Programme of the Youth, Peace and Security Conference

1 Wednesday, 23 May European Parliament – open to all participants – 12:00 – 13:00 Registration European Parliament Accreditation Centre (right-hand side of the Simone Veil Agora entrance to the Altiero Spinelli building) 13:00 – 14:00 Buffet lunch reception Members’ Restaurant, Altiero Spinelli building 14:00 – 15:00 Opening Session Room 5G-3, Altiero Spinelli building Keynote Address by Mr. Antonio Tajani, President of the European Parliament Chair Ms. Heidi Hautala, Vice-President of the European Parliament Speakers Ms. Mariya Gabriel, EU Commissioner for Digital Economy and Society Mr. Oscar Fernandez-Taranco, UN Assistant Secretary-General for Peacebuilding Support Ms. Ivana Tufegdzic, fYROM, EP Young Political Leaders Mr. Dereje Wordofa, UNFPA Deputy Executive Director Ms. Nour Kaabi, Tunisia, NET-MED Youth – UNESCO Mr. Oyewole Simon Oginni, Nigeria, Former AU-EU Youth Fellow 2 15:00 – 16:30 Parallel Thematic Panel Discussions Panel I Youth inclusion for conflict prevention and sustaining peace Library reading room, Altiero Spinelli building Discussants Ms. Soraya Post, Member of the European Parliament Mr. Oscar Fernandez-Taranco, UN Assistant Secretary-General for Peacebuilding Support Mr. Christian Leffler, Deputy Secretary-General, European External Action Service Mr. Amnon Morag, Israel, EP Young Political Leaders Ms. Hela Slim, France, Former AU-EU Youth Fellow Mr. MacDonald K. Munyoro, Zimbabwe, EP Young Political Leaders Facilitator Ms. Gizem Kilinc, United Network of Young Peacebuilders Panel II Young people innovating for peace Library room 128, Altiero Spinelli building Discussants Ms. Barbara Pesce-Monteiro, Director, UN/UNDP Representation Office in Brussels Ms. Anna-Katharina Deininger, OSCE CiO Special Representative and OSG Focal Point on Youth and Security Ms. -

13273 PSA Conf Programme 2011 PRINT

Transforming Politics: New Synergies 61st Annual International Conference 18 – 21 April 2011 Novotel London West, London, UK PSA 61st Annual International Conference London, 18 –21 April 2011 www.psa.ac.uk/2011 A Word of Welcome Dear Conference delegate You are extremely welcome to this 61st Conference of the Political Studies Association, held in the UK capital. The recently refurbished Hammersmith Novotel hotel offers high quality conference facilities all under one roof. We are expecting well over 500 delegates, representing over 50 different countries. There are more than 190 panels, as well as the workshops on Monday, building on last year’s innovation, and as a new addition, dedicated posters sessions. There are also three receptions. The Conference theme is ‘Transforming Politics: New Synergies’. Keynote speakers include Professor Carole Pateman, President of APSA, revisiting the concept of participatory democracy and Professor Iain McLean giving the Government and Opposition-sponsored Leonard Schapiro lecture on the subject of coalition and minority government. On Wednesday, our after-dinner speaker is Professor Tony Wright, (UCL and Birkbeck College) former MP and Chair of the Public Administration Select Committee. Amongst other highlights, Professor Vicente Palermo will discuss Anglo-Argentine relations and John Denham MP will talk on ‘English questions’ and the Labour Party’ and Sir Michael Aaronson, former Director General of Save the Children, will be drawing on his experience working in crisis situations to reflect on whether we had a choice in Libya today. Despite the worsening economic and policy environment, this has been a particularly active and successful year for the Association. Overall membership figures, including those for the new Teachers’ Section, continue to rise. -

Atti Parlamentari Della Biblioteca "Giovarmi Spadolini" Del Senato L'8 Ottobre

SENATO DELLA REPUBBLICA XVII LEGISLATURA Doc. C LXXII n. 1 RELAZI ONE SULLE ATTIVITA` SVOLTE DAGLI ENTI A CARATTERE INTERNAZIONALISTICO SOTTOPOSTI ALLA VIGILANZA DEL MINISTERO DEGLI AFFARI ESTERI (Anno 2012) (Articolo 3, quarto comma, della legge 28 dicembre 1982, n. 948) Presentata dal Ministro degli affari esteri (BONINO) Comunicata alla Presidenza il 16 settembre 2013 PAGINA BIANCA Camera dei Deputati —3— Senato della Repubblica XVII LEGISLATURA — DISEGNI DI LEGGE E RELAZIONI — DOCUMENTI INDICE Premessa ................................................................................... Pag. 5 1. Considerazioni d’insieme ................................................... » 6 1.1. Attività degli enti ......................................................... » 7 1.2. Collaborazione fra enti ............................................... » 10 1.3. Entità dei contributi statali ....................................... » 10 1.4. Risorse degli Enti e incidenza dei contributi ordinari statali sui bilanci ......................................................... » 11 1.5. Esercizio della funzione di vigilanza ....................... » 11 2. Contributi ............................................................................ » 13 2.1. Contributi ordinari (articolo 1) ................................. » 13 2.2. Contributi straordinari (articolo 2) .......................... » 15 2.3. Serie storica 2006-2012 dei contributi agli Enti internazionalistici beneficiari della legge n. 948 del 1982 .............................................................................. -

Title Items-In-Visits of Heads of States and Foreign Ministers

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page Date 15/06/2006 Time 4:59:15PM S-0907-0001 -01 -00001 Expanded Number S-0907-0001 -01 -00001 Title items-in-Visits of heads of states and foreign ministers Date Created 17/03/1977 Record Type Archival Item Container s-0907-0001: Correspondence with heads-of-state 1965-1981 Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit •3 felt^ri ly^f i ent of Public Information ^ & & <3 fciiW^ § ^ %•:£ « Pres™ s Sectio^ n United Nations, New York Note Ko. <3248/Rev.3 25 September 1981 KOTE TO CORRESPONDENTS HEADS OF STATE OR GOVERNMENT AND MINISTERS TO ATTEND GENERAL ASSEMBLY SESSION The Secretariat has been officially informed so far that the Heads of State or Government of 12 countries, 10 Deputy Prime Ministers or Vice- Presidents, 124 Ministers for Foreign Affairs and five other Ministers will be present during the thirty-sixth regular session of the General Assembly. Changes, deletions and additions will be available in subsequent revisions of this release. Heads of State or Government George C, Price, Prime Minister of Belize Mary E. Charles, Prime Minister and Minister for Finance and External Affairs of Dominica Jose Napoleon Duarte, President of El Salvador Ptolemy A. Reid, Prime Minister of Guyana Daniel T. arap fcoi, President of Kenya Mcussa Traore, President of Mali Eeewcosagur Ramgoolare, Prime Minister of Haur itius Seyni Kountche, President of the Higer Aristides Royo, President of Panama Prem Tinsulancnda, Prime Minister of Thailand Walter Hadye Lini, Prime Minister and Kinister for Foreign Affairs of Vanuatu Luis Herrera Campins, President of Venezuela (more) For information media — not an official record Office of Public Information Press Section United Nations, New York Note Ho. -

ICRC President in Italy…

INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS ICRC President in Italy... The President of the ICRC, Mr. Alexandre Hay, was in Italy from 15 to 20 June for an official visit. He was accompanied by Mr. Sergio Nessi, head of the Financing Division, and Mr. Melchior Borsinger, delegate-general for Europe and North America. The purpose of the visit was to contact the Italian authorities, to give them a detailed account of the ICRC role and function and to obtain greater moral and material support from them. The first day of the visit was mainly devoted to discussions with the leaders of the National Red Cross Society and a tour of the Society's principal installations. On the same day Mr. Hay was received by the President of the Republic, Mr. Sandro Pertini. Other discussions with government officials enabled the ICRC delegation to explain all aspects of current ICRC activities throughout the world. Mr. Hay's interlocutors were Mr. Filippo Maria Pandolfi, Minister of Finance; Mr. Aldo Aniasi, Minister of Health; Mrs. Nilde Iotti, Chairman of the Chamber of Deputies; Mr. Amintore Fanfani, President of the Senate; Mr. Paulo Emilio Taviani, Chairman of the Chamber of Deputies' Foreign Affairs Commission and Mr. Giulio Andreotti, Chairman of the Senate Foreign Affairs Commission. Discussions were held also with the leaders of the Italian main political parties. On 20 June President Hay, Mr. Nessi and Mr. Borsinger were received in audience by H.H. Pope John-Paul II, after conferring with H.E. Cardinal Casaroli, the Vatican Secretary of State, and H.E. Cardinal Gantin, Chairman of the "Cor Unum" Pontifical Council and of the pontifical Justice and Peace Commission. -

Download (515Kb)

European Community No. 26/1984 July 10, 1984 Contact: Ella Krucoff (202) 862-9540 THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT: 1984 ELECTION RESULTS :The newly elected European Parliament - the second to be chosen directly by European voters -- began its five-year term last month with an inaugural session in Strasbourg~ France. The Parliament elected Pierre Pflimlin, a French Christian Democrat, as its new president. Pflimlin, a parliamentarian since 1979, is a former Prime Minister of France and ex-mayor of Strasbourg. Be succeeds Pieter Dankert, a Dutch Socialist, who came in second in the presidential vote this time around. The new assembly quickly exercised one of its major powers -- final say over the European Community budget -- by blocking payment of a L983 budget rebate to the United Kingdom. The rebate had been approved by Community leaders as part of an overall plan to resolve the E.C.'s financial problems. The Parliament froze the rebate after the U.K. opposed a plan for covering a 1984 budget shortfall during a July Council of Ministers meeting. The issue will be discussed again in September by E.C. institutions. Garret FitzGerald, Prime Minister of Ireland, outlined for the Parliament the goals of Ireland's six-month presidency of the E.C. Council. Be urged the representatives to continue working for a more unified Europe in which "free movement of people and goods" is a reality, and he called for more "intensified common action" to fight unemployment. Be said European politicians must work to bolster the public's faith in the E.C., noting that budget problems and inter-governmental "wrangles" have overshadolted the Community's benefits. -

The Schengen Agreements and Their Impact on Euro- Mediterranean Relations the Case of Italy and the Maghreb

125 The Schengen Agreements and their Impact on Euro- Mediterranean Relations The Case of Italy and the Maghreb Simone PAOLI What were the main reasons that, between the mid-1980s and the early 1990s, a group of member states of the European Community (EC) agreed to abolish internal border controls while, simultaneously, building up external border controls? Why did they act outside the framework of the EC and initially exclude the Southern members of the Community? What were the reactions of both Northern and Southern Mediter- ranean countries to these intergovernmental accords, known as the Schengen agree- ments? What was their impact on both European and Euro-Mediterranean relations? And what were the implications of the accession of Southern members of the EC to said agreements in terms of relations with third Mediterranean countries? The present article cannot, of course, give a comprehensive answer to all these complex questions. It has nonetheless the ambition of throwing a new light on the origins of the Schengen agreements. In particular, by reconstructing the five-year long process through which Italy entered the Schengen Agreement and the Conven- tion implementing the Schengen Agreement, it will contribute towards the reinter- pretation of: the motives behind the Schengen agreements; migration relations be- tween Northern and Southern members of the EC in the 1980s; and migration relations between the EC, especially its Southern members, and third Mediterranean countries in the same decade. The article is divided into three parts. The first examines the historical background of the Schengen agreements, by placing them within the context of Euro-Mediter- ranean migration relations; it, also, presents the main arguments. -

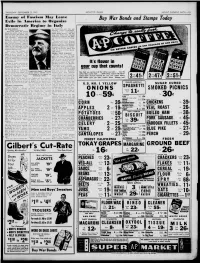

Gilbert S Cut-Rate I

THURSDAY—SEPTEMBER 23, 1943 MONITOR LEADER MOUNT CLEMENS, MICH 13 Ent k inv oh* May L« kav«* Buy War Bonds and Stamps Today Exile in i\meriea to Orijaiiixe w • ll€kiiioi*ralir hi Italy BY KAY HALLE ter Fiammetta. and his son Written for M A Service Sforzino reached Bordeaux, Within 25 year* the United where they m* to board a States has Riven refuge to two Dutch tramp steamer. For five great European Democrats who long days before they reached were far from the end of their Falmouth in England, the Sfor- rope politically. Thomas Mas- zas lived on nothing but orang- aryk. the Czech patriot, after es. a self-imposed exile on spending It war his old friend, Winston shores, return ! after World our Churchill, who finally received to it War I his homrlan after Sforza in London. the The Battle of had been freed from German Britain yoke—as the had commenced. Church- the President of approved to pro- newly-formed Republic—- ill Sforza side i Czech ceed to the United States and after modeled our own. keep the cause of Italian democ- Now, with the collapse of racy aflame. famous exile Italy, another HEADS “FREE ITALIANS” He -* an... JC. -a seems to be 01. the march. J two-year Sforza’-i American . is Count Carlo Sforza, for 20 exile has been spent in New’ years the uncompromising lead- apartment—- opposition York in a modest er of the Democratic that is, he not touring to Italy when is to Fascism. His return the country lecturing and or- imminent seem gazing the affairs of the 300,- Sforza is widely reg rded as in 000 It's flnuor Free Italians in the Western the one Italian who could re- Hemisphere, w hom \e leads construct a democratic form of His New York apartment is government for Italy. -

«Sì Al Centro Dell'ulivo» Dini Risponde Ai Popolari

05POL01A0507 05POL03A0507 FLOWPAGE ZALLCALL 13 14:43:22 07/07/96 K IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII Venerdì 5 luglio 1996 l’Unità pagina IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIPoliticaIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII 5 Marini apprezza. Il problema leadership: Prodi pensa al governo Bettino scomunica Amato «Sì al centro dell’Ulivo» e Martelli ROMA. E‘ dalle colonne del Dini risponde ai Popolari —quotidiano di An ‘Il Secolo d’Italia‘ che Bettino Craxi rinnova la sua ’scomunica‘ a Giuliano Amato ed Dini risponde ai Popolari: sono d’accordo, facciamo insie- esorta i socialisti italiani a riprende- re in proprio l’iniziativa politica. me il centro dell’Ulivo. E Marini: siamo aperti al dialogo. Craxi definisce l’adesione di Amato Ma nasce il problema della leadership. Chi deve essere il alla cosiddetta ‘Cosa 2‘ ’’una sem- capo: Prodi, come vorrebbero i Popolari o Dini, come au- plice operazione del tutto persona- spica Rinnovamento italiano? Masi: «Prodi è capo della le” e “tutt’altro che politica’’. E al 05POL01AF01 05POL01AF03 dottor Sottile manda un messaggio: coalizione e del governo, non può essere leader della fede- Not Found ’’la politica e‘ una cosa difficile e razione di centro». Silenzio del capo del governo. Per ora Not Found per fare politica bisogna rappre- non risponde alle proposte dei Popolari. 05POL01AF01 05POL01AF03 sentare qualcosa o qualcuno. Altri- GerardoBianco, menti ci si dedichi ad altro: per adestra,ilministro esempio, a scrivere libri...’’. degliEsteri L’appello ai socialisti da Ham- RITANNA ARMENI LambertoDini, mamet e‘ dunque a “rinascere da ROMA. Marini propone a Dini tuazione con grande attenzione. inbasso, soli’’. “Perche‘ se non stai da solo - —di costruire insieme un centro più Ma in questa fibrillazione della EnricoBoselli dice Craxi al suo intervistatore- sei forte dell’Ulivo.